Guan Zhixun & Fan Hong ~ Body and Politics: Elite Disability Sport in China

There has been growing interest in research on disability sport internationally, yet little research has concentrated on the development of disability sport in China. This book focuses on elite disability sport in China in the context of history, politics, policies and practice from 1979 to 2012. It examines the relationship between athletes with disabilities and the three major disability games: the Paralympic Games, the Special Olympic Games and the Deaflympic Games. Three key questions are asked: What policies have ensured the success of elite disability sport? How do the elite sport system and management of elite disability sport work in China? In what way has elite disability sport empowered athletes with disabilities in China?

There has been growing interest in research on disability sport internationally, yet little research has concentrated on the development of disability sport in China. This book focuses on elite disability sport in China in the context of history, politics, policies and practice from 1979 to 2012. It examines the relationship between athletes with disabilities and the three major disability games: the Paralympic Games, the Special Olympic Games and the Deaflympic Games. Three key questions are asked: What policies have ensured the success of elite disability sport? How do the elite sport system and management of elite disability sport work in China? In what way has elite disability sport empowered athletes with disabilities in China?

The book includes a comprehensive literature review on the historical development of disability sport in China and beyond. Functionalism and empowerment are the major theoretical backgrounds for the research. The former analyses the function of elite sport policies, systems and other factors occurring during the process, whilst the latter examines the relationship of empowerment between elite disability sport and athletes in China. The three major disability competitions are used as case studies. A qualitative research methodology with specific methods of semi–structured interviews, data collection and documentary analysis is applied to the research. The thesis concludes that the development of elite disability sport in China has received strong support from the government. Elite disability sport is closely linked with China’s politics and international image. The success of athletes with disabilities on the international stage has raised the awareness of the issues facing people with disabilities. This has changed their image in Chinese society in general, and has empowered athletes with disabilities in particular. However, there is unbalanced development in elite disability sport. The book concludes by indicating some potential future directions for further research.

Nova Science Publishers, New York, 2018. Asian Studies. ISBN: 978-1-53613-510-7

Asian Studies (Series Editors: Fan Hong, Auke van der Berg and Peter Herrmann – Bangor University, UK, Rozenberg Quarterly, Netherlands and EURISPES – Istituto di Studi Politici, Economici e Sociali, Italy)

More information: https://novapublishers.com/shop/body-and-politics-elite-disability-sport-in-china/

Minako O’Hagan & Qi Zhang ~ Conflict And Communication: A Changing Asia In A Globalizing World – Language And Cultural Perspectives

The chapters within this volume comprise selected papers from the 5th Annual Conference of the Asian Studies Irish Association (A.S.I.A.) held at Dublin City University in November 2013. Discussing the conference theme Conflict and Communication: A Changing Asia in a Globalising World, this volume presents multiple perspectives articulated by scholars across disciplines that include translation studies, language studies, literary studies and computer science.

The chapters within this volume comprise selected papers from the 5th Annual Conference of the Asian Studies Irish Association (A.S.I.A.) held at Dublin City University in November 2013. Discussing the conference theme Conflict and Communication: A Changing Asia in a Globalising World, this volume presents multiple perspectives articulated by scholars across disciplines that include translation studies, language studies, literary studies and computer science.

Within such disciplinary diversity emerged a unity which converged on language and culture as fundamental points of analysis. This volume covers research topics relating to China, Korea, Japan, Thailand, and Vietnam, as well as Asia as a whole in a globalising world. Insights shared by the ten authors each addressing Asia through a different disciplinary lens hope to provide future research impetus for students and established scholars alike within and beyond Asian Studies.

(Series Editors: Fan Hong, Auke van der Berg and Peter Herrmann – Bangor University, UK, Rozenberg Quarterly, Netherlands and EURISPES – Istituto di Studi Politici, Economici e Sociali, Italy)

Zhang Muchun & Fan Hong ~ The Sino-Indian Border War And The Foreign Policies Of China And India (1950-1965)

There has been growing interest in the historical analysis of the Sino-Indian relations and the Sino-Indian border issue, yet little research has focused on the impact of two government’s foreign policies concerning the Sino-Indian border issue and border war. This book examines the Sino-Indian relations, particularly the Sino-Indian border issue and border war, Tibetan issues, and China and India’s foreign policies from the 1950s to 1960s. This book will discuss the origin and development of the Sino-Indian border issue and connections between national diplomatic policies and the border disputes in China and India.

There has been growing interest in the historical analysis of the Sino-Indian relations and the Sino-Indian border issue, yet little research has focused on the impact of two government’s foreign policies concerning the Sino-Indian border issue and border war. This book examines the Sino-Indian relations, particularly the Sino-Indian border issue and border war, Tibetan issues, and China and India’s foreign policies from the 1950s to 1960s. This book will discuss the origin and development of the Sino-Indian border issue and connections between national diplomatic policies and the border disputes in China and India.

More specifically, this book aims to illustrate the origins of the Sino-Indian border dispute, the role Tibet played in the Sino-Indian border issue, the impacts of their foreign policies on the Sino-Indian border issue from the 1950s to the 1960s, the measures both states took to ease boundary tensions and conflicts, the reasons for the outbreak of the 1962 Border War, and the changes to foreign policies the two governments made before and after the 1962 Border War. This book involves the collection and analysis of historical archival materials and official documents from both China and India.

The book is mainly aimed at researchers, undergraduates and postgraduate students in the subject areas of the history of international relations and Chinese studies. It could be used in a wide range of courses since it offers insights into the aspects of historical and international relations found within Chinese society. It will be of interest to academic libraries, research institutes, universities, and students either as a textbook or as reading material. Due to the appeal and relevance of the subject, this book would also be of interest to people who want to know more about the history of Sino-Indian border disputes as well as China and India’s foreign policies from 1950 to the 1960s through such a particular and appropriate topic.

Asian Studies (Series Editors: Fan Hong, Auke van der Berg and Peter Herrmann – Bangor University, UK, Rozenberg Quarterly, Netherlands and EURISPES – Istituto di Studi Politici, Economici e Sociali, Italy) – Nova Science Publishers, New York, 2018 – ISBN 978-1-53613-770-5

Got to: https://www.novapublishers.com/

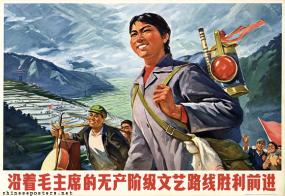

The Rise And Fall Of The “Up To The Mountains And Down To The Countryside” Movement: A Historical Review

Abstract

Abstract

The Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside (UMDC) Movement (上山下乡运动) was an important event in the history of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). It changed the fate of a whole generation of Chinese and had far-reaching effects on the history of the PRC. As a nationwide urban-to-rural migration (i.e. the reverse of the urbanization process), it is also unique in human history for its complex origin and the wide scope of its impact (16 million urban youths and nearly every Chinese family), as well as its long duration, tortuous process, and contradictory attributes. However, compared to the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and other political events of the 1960s, the UMDC Movement is rarely known to people who are unfamiliar with Chinese history. Even in the area of Chinese Studies, the UMDC Movement has been misunderstood as a constituent part or a ramification of the Cultural Revolution. This paper reviews the process of the development of the UMDC Movement and analyses the social structural factors in its rise and fall in Chinese history.

Introduction

From 1967 to 1979, more than 16 million[i] Chinese urban youths were sent to the countryside to engage in agricultural production. This was known as the Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement (上山下乡运动). Those 16 million participants, who were named Zhiqing (educated youth 知青) after this movement, lived and worked in the countryside as ordinary agricultural labourers during their teenage years. In the early 1980s, when most Zhiqing eventually returned to the city, they were immediately faced with the residual issues of the UMDC Movement as well as the challenge of readjusting to urban society.

The UMDC Movement not only changed the fate of a whole generation of Chinese but also had far-reaching effects on the history of the People’s Republic of China. However, in overseas Chinese Studies, much less attention has been given to the UMDC Movement than to the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). For many researchers, the UMDC Movement is a constituent part or a ramification of the Cultural Revolution.[ii] In terms of the relationship between the two historical events, the Zhiqing Office of the State Council announced an official conclusion in 1981:

“First of all, the ‘UMDC’ was a major experiment carried out by the Communist Party fromthe 1950s, based on fundamental realities of the country, which then had a large population, a weak economic foundation, and employment difficulties; it was not the result of the Cultural Revolution. Second, the ‘UMDC’ was aimed primarily at resolving employment problems; during the ten years of the Cultural Revolution, it evolved as a political movement under the ultra-left ideology and resulted in serious mistakes in practice.”[iii] (Gu 1997, pp. 283–285)

As indicated in the above quotation, the UMDC Movement was characterized by its complex origin, tortuous process, and contradictory attributes. Simply associating it with the Cultural Revolution has led to the neglect of these historical facts. Therefore, to clarify the unique and significant position of the UMDC Movement in Chinese history, this paper reviews its rise and fall and further argues that its origin, development, and termination were all rooted in structural and fundamental contradictions of Chinese society, as well as the evolution of these contradictions under different historical circumstances.

Another theme of this chapter is to identify the Zhiqing’s position in the history of the UMDC Movement and in Chinese society. The UMDC Movement created the Zhiqing group – a whole generation of youths who have been allocated “Zhiqing” as their collective identity. Based on the historical review, this chapter argues that the constitution of the Zhiqing group and the connotation of the Zhiqing identity both underwent transformations at different stages of the UMDC Movement.

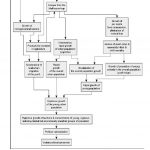

To summarize, a comprehensive historical review lays the foundation for an advanced understanding of the UMDC Movement and Zhiqing. The following sections present a clear development process, including a pre-movement phase and three distinct stages of the UMDC Movement.

Pre-Movement Phase: 1953–1965

Mobilizing and organizing the Chinese youth to engage in agriculture can be traced back to the 1950s. After 1953, the problems caused by the country’s overheated economy became acute. Large numbers of rural youths rushed into the cities to search for jobs. To alleviate employment pressure in the cities, the state sought to encourage these rural youths to go back to their home villages and engage in agricultural production. Those rural youth were called HuixiangZhiqing to distinguish them from the subsequent Zhiqing – urban youth. Because they were originally from the countryside, their return was regarded as normal and they were not entitled to a resettlement fee or other preferential treatments which were provided to urban youth when they settled down in the countryside. In addition to urban unemployment, another influencing economic factor was the development of agricultural cooperatives. Mao Zedong, the major promoter of rural collectivization, emphasized his opinion that educated young people should move to remote rural areas to make contributions to the nation and achieve personal development.[iv]

Another significant development in the 1950s was youth reclamation teams, which were arranged, organized, and guided directly by the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League. The two models used for these teams were the Beijing Youth Voluntary Reclamation Team(北京市青年志愿垦荒队) and the Shanghai Youth Voluntary Reclamation Team (上海市青年志愿垦荒队).[v] Driven by the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League, youth reclamation teams soon spread throughout the whole country as a new trend. However, they came to an end in 1956 because of economic deficiency and poor management (Ding, 1998, pp.60–68). Moreover, the majority of the urban youths in these reclamation teams failed to adapt to intense farm work and harsh conditions, and they did not settle down in the countryside as they were supposed to (Ding, 1998, p. 60).

The Huixiang Zhiqing and the youth reclamation teams were the predecessors of the Zhiqing. Apart from this successive relationship, the dilemmas they faced in the 1950s continued to influence the UMDC Movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Subsequent history has demonstrated that these dilemmas, revealed later as inherent problems of the UMDC Movement, had determined in advance its direction and final results.

Of those dilemmas and problems, the most significant one was the employment issue, which cyclically intensified alongside general economic fluctuations. This was relevant with regard to the contradiction between population growth and development in the economy and education, as well as shortcomings in population, economy, and education policies. The second and consequent problem was that employment pressure and other social problems in the cities were often shifted to the countryside. Lastly, turning educated young people into simple labourers objectively resulted in a waste of human and education resources. Initially, it was hoped that young people would contribute to rural construction by exploiting their knowledge and skills and transforming the rural society with advanced urban culture. However, most urban youths failed to settle down in the countryside. So the ironic fact was that “educated young people were less capable than illiterate peasants” (Ding, 1998, p.63). It is clear now that this was due to the poor production conditions, which stopped these young people from using their advantages. However, in that particular historical period, these young people’s failure and resistance were interpreted ideologically as the weakness and individualism of the bourgeoisie.[vi]

After a few years of try-outs, in 1956, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the state decided to adopt mobilizing youth to the countryside as a conventional method to address the employment issue. This time, the urban youth became the target for mobilization. On 23 January 1956, the Political Bureau of the CCP Central Committee (中共中央政治局) issued an “Outline of National Agricultural Development from 1956 to 1967 (draft)” (1956 年到 1967 年全国农业发展纲要[草案]). According to Article Thirty of the Outline, graduates of urban secondary and primary schools, except for those who had managed to enter into further studies and those who had found jobs in the cities, should respond to the call and go down to the countryside and up to mountains to join in agricultural production and participate in the great cause of socialist agricultural construction. For the first time, “Down to the Countryside and Up to the Mountains” (下乡上山) appeared in an official document as a set term, though the sequence here was contrary to the later well-known expression, “Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside” (上山下乡).

In 1958, under the impact of the Great Leap Forward, the implementation of “Down to the Countryside and Up to the Mountains” was halted suddenly. By the end of 1962, the number of idle urban youths had reached 2 million.[vii] Soon, the UMDC work was brought back onto the agenda. In October of 1962, the Agriculture and Forestry Office of the State Council (国务院农林办) held the “Reporting Conference of Resettling Urban Redundant Staff and Young Students in State Farms, Forest Farms, Pastures, and Fisheries (关于国营农林牧渔场安置家居大中城市精简职工和青年学生的汇报会议). Zhou Enlai attended the meeting and delivered a speech. In this speech, he pointed out that resettling the urban population in the countryside was an effective solution to the problem of surplus labour forces in the city. Participants discussed a series of practical issues, including the target and methods of resettlement, expenditure, and resources, as well as corresponding policies, plans, and safeguards. At this meeting, the Leading Group of Resettlement Work of Agriculture and Forestry Office (农林办安置领导小组) was founded, which was the predecessor to the Leading Group Office of Zhiqing UMDC (知识青年上山下乡领导小组办公室). Read more

Purifying Islamic Equities ~ The Interest Tax Shield

Abstract

This paper seeks to add to the debate regarding the appropriate methodology to purify tainted components from shari’ah compliant equities. Based on the Qur’anical prohibition against riba and an analysis of the purification methodology recommended by AAOIFI Shari’ah Standard 21, this paper highlights shortcomings in Standard 21 and references the corporate finance literature to argue for the need to also purify the interest tax shield from debt. Purification is a pivotal element of the Islamic investment process yet Standard 21 permits a loose interpretation which causes portfolios to be under-purified. Standard 21 also makes no mention of the interest tax shield from debt even though the benefits there from are at odds with the principles of social justice in Islam. That there is no mention of the interest tax shield from debt in the (limited) literature on the purification of Islamic equities is puzzling. This paper has implications for the Islamic funds industry as well as for compliant Muslim investors.

Introduction

The Islamic funds industry is estimated at 5.5 per cent (Ernst & Young, 2011) of the over $1.0 trillion (Wilson, 2009) global Islamic finance industry. Although small in comparison with the conventional funds industry, the potential growth from targeting the largely untapped Muslim market (estimated at 23 per cent of the world’s population) has garnered significant attention (Hassan and Girard, 2011). But the nascent Islamic funds industry is already at a crossroads. There are a number of issues which could derail its early promise – chief among these is confusion about how to purify Islamic portfolios to ensure shari’ah compliance.

Purification refers to the need to quantify and donate to charity all impure components deemed unacceptable under shari’ah principles and teachings (Elgari, 2000). Impure components include riba, which in modern Islamic finance has become synonymous with interest-related activity and is unequivocally prohibited in the Qur’an. Because nearly every company in the world receives/pays interest on its cash/debt balances, the practical effect of an absolute interpretation of the prohibition against riba is that the funds industry is, ipso facto, off limits for Muslim investors (Moore, 1997; McMillen, 2011). As a result, the shari’ah Supervisory Boards (hereafter SSBs) that determine the compliance of any investment have had to make a number of compromises to allow some permissible variation from absolute shari’ah principles. While some research has been done relating to the construction and application of Islamic stock screens, there is a paucity of literature about how haram elements resulting from permissible variation should be purified.[i],[ii] Although the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) recommends one method for purging impure amounts in Shari’ah Standard 21 Financial Papers (Shares and Bonds) (hereafter S21), the terminology used throughout is not consistent and, in certain sections, lacks specificity. Also, not all jurists adhere to AAOIFI standards such that several methods are used in practice. The result is that, even for those adhering to AAOIFI standards, differing interpretations are possible, meaning that confusion remains and haram components go unpurified. To some shari’ah scholars, the entire permissibility of an Islamic fund hinges on purification, so this lacuna needs to be addressed (Elgari, 2000).

This paper discusses the unequivocal prohibition against riba in the Qur’an and the hadith, and its impact on commercial activity in the Islamic world. It documents how the practice of permissible variation has evolved in the Islamic funds industry to allow a degree of deviation from absolute concepts and analyses some of the various current methodologies suggested for purging the consequent impurities from Islamic portfolios, with a focus on S21. Given what is at stake for the nascent Islamic funds industry, this chapter also suggests a comprehensive methodology for the purification of prohibited components which includes the need to also purify the benefits from the interest tax shield from debt −the benefits of which to the firm are well understood in the corporate finance literature.

Islam and Commercial Activity

Islam is a complete way of life, a lifestyle which constitutes a part of every Muslim’s cultural and spiritual identity (Abbasi, Holman,andMurray, 1989; DeLorenzo, 2002). Islam aims at striking a balance between individual freedoms (including commercial activities, Qu’ran 62:10) and ensuring that these freedoms are conducive to the growth and benefit of society at large (Ebrahim, 2003). Indeed, the Qur’an and the Sunnah (Islamic custom and practice) place tremendous stress on justice. All leading jurists therefore, without exception, have held that justice is a central indispensable ingredient of the maqasid al-shari’ah, or the goals of Islam (Chapra, 2000). In economics, justice can be interpreted to mean that resources are used in a manner that ensures, inter alia, the equitable distribution of income and wealth and economic stability (Chapra, 2000). Since the emergence of post-independence Muslim states in the global economy in the 1960s, there has been much debate about how commercial activity, and for this chapter the Islamic funds industry specifically, can be organized to conform to Islamic justice and shari’ah. Chapra (2000) contends that these goals cannot be realized without a humanitarian strategy which injects a moral dimension into economics — the prohibition against riba is part of this moral dimension. Read more

The Case Of “Fukushima” ~ Notation Choice As A Highlighting Device In Ad Hoc Concept Construction

Abstract

Abstract

The irregular use of katakana has been analysed mainly in descriptive terms and is often considered to be a device for creating homonyms or communicating emotions (See Ogakiuchi, 2010). This chapter examines the irregular use of katakana notation from the perspective of relevance theory. Unlike previous studies, which have focused on the images and emotions the katakana notation system is said to communicate, this chapter focuses on concepts communicated by the use of words when they are written in katakana rather than other usual notations. I show that the irregular use of katakana is just one of many devices used for highlighting ad hoc concepts that can be found universally and should be analysed in a wider context than describing the functions of this notation,which is unique to Japanese. I argue that a cognitively grounded relevance theoretic account, in particular the notions of ad hoc concepts and metarepresentation, enables us to provide an explanation for observations made in previous studies.

The paper concludes that emotions attributed to the use of katakana and the homonyms which katakana notation appears to create can be explained in terms of repeated metarepresentation of ad hoc concepts and attributed thoughts communicated by the concepts.

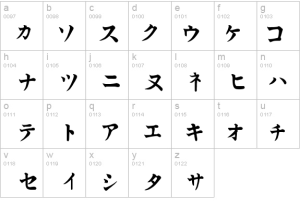

Introduction –The Japanese Writing System

The Japanese writing system uses three different types of notation. The first is kanji, which is logographic. Each kanji character has a “meaning” and is used for conceptual words. There are also two alphabet systems, hiragana and katakana. Hiragana is phonographic and used for particles, connectives, and other “function words”, as well as being used by children (and adults) when they do not know which kanji to use. Katakana is also phonographic and is mainly used for loan words, onomatopoeia, and the names of animals, species, flowers, etc. It is convention that all three notation systems are used as required. Example (1) demonstrates this:

(1) ジョンの 庭にネコが 入ってきた.

John no niwa ni neko ga haitte kita

John GEN garden LOC cat SUB entered

“A cat came into John’s garden.”

In (1), two conceptual words,“garden”and “enter”, are written in kanji: 庭 and 入, respectively. Hiragana is used for particles,“no” (の) and “ni” (に), part of verb conjugation (ってきた), and the subject marker“ga” (が). Although they are conceptual words, katakana is used for “John” (ジョン) and “cat” (ネコ) as John is non-Japanese and “cat” is the name of an animal.

The choice of notation system is based on this convention and one’s ability – if one does not know or remember how to write a certain kanji, one might choose to write the word in hiragana or katakana. This is particularly the case for children and in hand-written texts. This paper does not aim to analyse these cases, where choice of notation is based on personal abilities. Nor does it deal with cases where katakana notation is used as it is expected to be. Instead, this study will focus on cases where the use of katakana cannot be explained in terms of personal abilities or preferences. In particular, I shall focus on cases in which katakana is used where it is not expected or not because of personal preference/abilities. A particular focus will be placed on correlations between choice of notation and construction of ad hoc concepts, where the use of katakana seems to trigger concept adjustment. See “Fukushima”in (2)[i]:

(2) チェルノブイリからフクシマへ「同じ道たどらないで」

Chernobyl kara Fukushima e “onaji michi tadoranaide”

Chernobyl FROM Fukushima LOC “same road follow-NEG-IMPERATIVE”

From Chernobyl to Fukushima: “Please do not go the way we did”

(Sekine 2011)

“Fukushima” is the name of a town and, normally, it is written as 福島 in kanji. However, in (2), it is written as フクシマ in katakana, and it seems to communicate more than just a name. What does it communicate? How is it different from “Fukushima” written in kanji? In following sections, I will first look at how katakana notation has been dealt with in previous studies and then present an alternative account from the perspective of relevance theory. Read more