Iraqi Jewish Archive

Preserving the Iraqi Jewish Archive

Preserving the Iraqi Jewish Archive

Startling evidence of the once vibrant Jewish life in Iraq came to light in May 2003 — over 2,700 books and tens of thousands of documents were discovered in the flooded basement of the Iraqi intelligence headquarters by a US Army team.

The remarkable survival of this written record of Iraqi Jewish life provides an unexpected opportunity to better understand this 2,500-year-old Jewish community. For centuries, it had flourished in what had generally been a tolerant, multicultural society. But circumstances changed dramatically for Jews in the mid-twentieth century, when most Iraqi Jews fled and were stripped of their citizenship and assets.

To provide accessibility throughout the world to the damaged materials found in 2003, the US National Archives and Records Administration and its partners have preserved, cataloged, and digitized the books and documents.

The IJA website: https://ijarchive.org

Searching the Iraqi Jewish Archive

Searching the Iraqi Jewish Archive is much like searching an electronic library catalog. To craft searches that will bring up the material that interests you, whether school records, Baghdadi chief rabbis, or laws governing the Jewish community, it is important to understand what is in a cataloging record. Records for books include the most complete publication information available and may include the title in its original language and in transliteration, author, Hebrew and secular dates of publication, place of publication, and publisher. This is followed by a short, two-to-three-sentence description of the book and then a list of keywords. Documents similarly have a title, description, and keywords. The results of any search will be a title or descriptive title plus a brief cataloging entry and a picture. Click to see a more extensive description as well as keywords related to the entry and a PDF of the actual book or archival record (these PDFs can be viewed on an online e-reader or downloaded). Suppose you searched for “Frank Iny School”: you would find not only student records but also bills, correspondence, receipts, and class rosters. To narrow a search to just student records, try a new search on the keyword “students”. The most common terms are included to facilitate searching. Transliteration follows the Library of Congress Rules of Romanization for Hebrew and for Arabic Alternate spellings for certain Hebrew and Arabic transliterations will continue to be added.

Search the collection: https://ijarchive.org/search

Correspondence to and from Rabbi Sasson Khedouri

This archival material includes most correspondence with Rabbi Sasson Khedouri.

Topics include: correspondence from Midrash Talmud Torah regarding educational and financial matters; election of members to a Management Committee for the Baghdad Brigade; letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding Rabbi Khedouri’s testimony before a British-American Commission of Inquiry on the state of Israel; document of questions and Rabbi Khedouri’s answers on the following issues: Jewish status in Iraq, the state of Israel, equality of Jews on paying taxes, education, obtaining jobs, business, religion freedom, travelling, teaching Hebrew, and the number of Jews in Iraq; a form to collect factual information on the Jewish community to be published in the al-Rafidain Directory; a letter from Iraq Red Crescent Society to the head of Jewish community regarding the death of three Iraqis in Java, Indonesia prisons; a letter from a researcher; an invitation for a theater play from the Children’s Protection Society; Shamash Company asking for help to distribute fabric to the poor; letter of complaint from a Muslim because some Jews entered the al-Kazmia holy place; a complaint regarding the Jewish community’s girls behavior; letter asking for help on a forgery matter; letter asking for help from a Russian Jew who moved to Baghdad; letter asking for help to get papers from the Ministry of Supply to print the Jewish annual calendar for 5708; letter from the al-Jafería Schools Association asking for book donations to build a library; letters to the head of the Jewish community regarding obituaries for martyrs; letter to write an introduction for a book about Iraqi Crown Prince Abdullah; letters from the President of the Jewish Community asking for help on some matters.

Go to: https://ijarchive.org/content/3108

Salima Murad – Iraqi Jewish singer (1900-1974) سليمة مراد

Eness Elias ~ Iraq Still Honors This Jewish Star Known as the ‘Voice of Baghdad’ – Haaretz (Published on 20.11.2018)

Salima Mourad takes the stage with her head slightly bowed and a big smile, wearing a sleeveless dress. She always looks stylish; she doesn’t shout it out, it’s simply part of her. She’s hypnotic. You can’t take your eyes off her, in the old film clips. She has a virtuosic voice that she uses in any way she sees fit, spanning a broad vocal range, singing softly and forte. She seems to know exactly what she’s doing. There’s a reason why Mourad, who passed away in 1974, is still considered one of the most famous and admired singers in Iraq.

Last week, a unique tribute was paid to Mourad within the framework of the Jerusalem International Oud Festival. Called “The Voice of Baghdad,” the event took place under the auspices of the city’s Confederation House and featured an impressive group of singers and instrumentalists, as part of a collaboration involving veteran producer and musician Yair Dalal, with artistic direction by Effie Benaya.

The life of Salima Mourad, who was born in 1900, sounds like something out of a Hollywood film: A young Jewish Iraqi woman begins to sing and turns out to be one of the greatest talents in the country and in the entire Arab world. She performs in the most prestigious venues, in cafes, at nightclubs and family parties, and becomes a famous and admired figure, as great as Egyptian singers Umm Kulthum and Laila Mourad – who was also Jewish.

Read more: https://www.haaretz.com/a-tribute-to-the-jewish-crooner-known-as-the-voice-of-baghdad

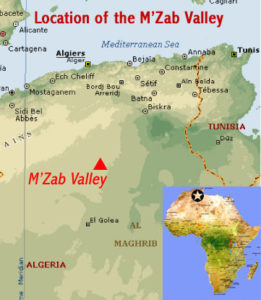

Rebecca A. Wall ~ The Jews Of The Desert: Colonialism, Zionism, And The Jews Of The Algerian M’zab, 1882-1962

University of Michigan, 2014. This dissertation studies the Jewish community of the Algerian M’zab during the French colonization of the Sahara from 1882 until 1962. French officials refused to extend the 1870 Crémieux Decree that emancipated Algerian Jews to the M’zab after its 1882 annexation. French administrators saw the M’zabi Jews as insurmountably different and consequently excluded them from emancipation. Despite petitions from the community and French and Algerian Jewish advocacy for extending emancipation to the south, successive French colonial and metropolitan governments declined to extend the Crémieux Decree to the M’zab. French officials justified this decision by invoking the insurmountable difference of M’zabi Jews, who were both too Jewish and too similar to Algerian Muslims to be “regenerated” as French citizens.

University of Michigan, 2014. This dissertation studies the Jewish community of the Algerian M’zab during the French colonization of the Sahara from 1882 until 1962. French officials refused to extend the 1870 Crémieux Decree that emancipated Algerian Jews to the M’zab after its 1882 annexation. French administrators saw the M’zabi Jews as insurmountably different and consequently excluded them from emancipation. Despite petitions from the community and French and Algerian Jewish advocacy for extending emancipation to the south, successive French colonial and metropolitan governments declined to extend the Crémieux Decree to the M’zab. French officials justified this decision by invoking the insurmountable difference of M’zabi Jews, who were both too Jewish and too similar to Algerian Muslims to be “regenerated” as French citizens.

Within the colonial legal system, M’zabi Jews were classified as “indigènes,” or natives, alongside Algerian Muslims. M’zabi Jews faced the restrictions that bounded the lives of Muslims in French Algeria and settler antisemitism that culminated in the Vichy abrogation of the Crémieux Decree in 1940. When Free French forces reinstated the Crémieux Decree in 1943, the French again excluded the M’zabi Jews. Following this, a number of individuals and families from the community left Algeria to join the growing Jewish community in British mandatory Palestine.

M’zabi Jews were the only organized Jewish community who left Algeria for Israel. Their history challenges historiography that claims Zionism was unsuccessful in Algeria. M’zabi Jews were not ardent Zionists, but they did take advantage of the opportunities for emigration made possible by international Zionist organizations including the American Joint Distribution Committee and the Jewish Agency. In contrast to the larger history of Algerian Jews, the history of the M’zabi Jewish immigration from Algeria to Israel is part of the larger history of Jewish migrations from the Arab world to Israel after 1945. M’zabi Jews won full French citizenship in late 1961, but most still opted to make their way to Israel rather than France.

The complete thesis

(PDF-format): https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/rawall_1.pdf

Stephanie Schwartz ~ Double-Diaspora In The Literature And Film of Arab Jews

Abstract

Abstract

Inspired by the contrapuntal and relational critiques of Edward Said and Ella Shohat, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of the literature and film of Arab Jews in order to deconstruct discourses on Jewish identity that privilege the dichotomies of Israel-diaspora and Arab-Jew. Sami Michael’s novel Refuge, Naim Kattan’s memoir Farewell, Babylon, Karin Albou’s film Little Jerusalem and b.h. Yael’s video documentary Fresh Blood: a Consideration of Belonging reveal the complexities and interconnections of Sephardic, Mizrahi and Arab Jewish experiences across multiple geographies that are often silenced under dominant Eurocentric, Ashkenazi or Zionist interpretations of Jewish history.

Drawing from these texts, Jewish identity is explored through four philosophical themes: Jewish beginnings vs. origins, boundaries between Arab and Jew, the construction of Jewish identities in place and space, and, the concept of diaspora and the importance Jewish difference. As a double-diaspora, with the two poles of their identities seen as enemies in the ongoing conflict between Israel-Palestine, Arab Jews challenge the conception of a single Jewish nation, ethnicity, identity or culture. Jewishness can better be understood as a rhizome, a system without a centre and made of heterogeneous component, that is able to create, recreate and move through multiple territories, rather than ever settling in, or being confined to a single form that seeks to dominate over others. This dissertation contributes a unique theoretical reading of Jewish cultures in the plural, and includes an examination of lesser known Arab Jewish writing and experimental documentary in Canada in relation to Iraq, France and Israel.

Thesis University of Ottawa, 2012: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/Schwartz_Stephanie_2012_thesis.pdf

The Mellah: The Historical Jewish Quarter

Mellah is the Jewish quarter in Morocco. The first official Mellah in Morocco was established in Fez in 1438. The Mellah is like a city within a city. This video takes one back to the history, via postcards, when the Mellah was inhabited by Jews and how it is different today.

Avi Beker ~ The Forgotten Narrative: Jewish Refugees From Arab Countries

Jewish Political Studies Review – Historically, there was an exchange of populations in the Middle East and the number of displaced Jews exceeds the number of Palestinian Arab refugees. Most of the Jews were expelled as a result of an open policy of anti-Semitic incitement and even ethnic cleansing. However, unlike the Arab refugees, the Jews who fled are a forgotten case because of a combination of international cynicism and domestic Israeli suppression of the subject. The Palestinians are the only group of refugees out of the more than one hundred million who were displaced after World War II who have a special UN agency that, according to its mandate, cannot but perpetuate their tragedy. An open debate about the exodus of the Jews is critical for countering the Palestinian demand for the “right of return” and will require a more objective scrutiny of the myths about the origins of the Arab- Israeli conflict.

Jewish Political Studies Review – Historically, there was an exchange of populations in the Middle East and the number of displaced Jews exceeds the number of Palestinian Arab refugees. Most of the Jews were expelled as a result of an open policy of anti-Semitic incitement and even ethnic cleansing. However, unlike the Arab refugees, the Jews who fled are a forgotten case because of a combination of international cynicism and domestic Israeli suppression of the subject. The Palestinians are the only group of refugees out of the more than one hundred million who were displaced after World War II who have a special UN agency that, according to its mandate, cannot but perpetuate their tragedy. An open debate about the exodus of the Jews is critical for countering the Palestinian demand for the “right of return” and will require a more objective scrutiny of the myths about the origins of the Arab- Israeli conflict.

Introduction

Why was the story of the Jewish refugees from Arab countries suppressed? How did it become a forgotten exodus?

Semha Alwaya, an attorney from San Francisco and former Jewish refugee from Iraq, wrote in March 2005 in the San Francisco Chronicle that the world is ignoring her story simply because of the “inconvenience for those who seek to blame Israel for all the problems in the Middle East.”1 As she notes, since 1949 the United Nations has passed more than a hundred resolutions on Palestinian refugees and not a single one on Jewish refugees from Arab countries. The UN makes a clear divide between the “right of return” of millions of refugees even into Israel proper (the pre-1967 borders) and the rights of these Jewish refugees.

Although they exceed the numbers of the Palestinian refugees, the Jews who fled are a forgotten case. Whereas the former are at the very heart of the peace process with a huge UN bureaucratic machinery dedicated to keeping them in the camps, the nine hundred thousand Jews who were forced out of Arab countries have not been refugees for many years. Most of them, about 650,000, went to Israel because it was the only country that would admit them. Most of them resided in tents that after several years were replaced by wooden cabins, and stayed in what were actually refugee camps for up to twelve years. They never received any aid or even attention from the UN Relief And Works Agency (UNRWA), the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, or any other international agency. Although their plight was raised almost every year at the UN by Israeli representatives, there was never any other reference to their case at the world body.

Only at the end of October 2003 was a bipartisan resolution (H. Con. Res. 311) submitted to the U.S. Congress that recognized the “Dual Middle East Refugee Problem.” It speaks of the forgotten exodus of nine hundred thousand Jews from Arab countries who “were forced to flee and in some cases brutally expelled amid coordinated violence and anti-Semitic incitement that amounted to ethnic cleansing.” Referring to the “population exchange” that took place in the Middle East, the resolution deplores the “cynical perpetuation of the Arab refugee crisis” and criticizes the “immense machinery of UNRWA” that only “increases violence through terror.” The resolution called on UNRWA to set up a program for resettling the Palestinian refugees.

Typically, the issue of the Jewish refugees was not on the agenda of the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations for a final settlement at Camp David in July 2000. The subject emerged only after the parties failed to reach an agreement on the issue of the Palestinian refugees. Only then did the Israelis raise the question of justice for the Jews from Arab countries.

In addition to the international constraints, there have been domestic political reasons for successive Israeli governments’ suppression of the subject. Many Israelis regarded the immigration and later integration of the Middle Eastern Jews into Israeli society as an important element in the Zionist ethos of the ingathering of exiles, and there was a reluctance to describe it in terms of a forced expulsion or, at best, an involuntary emigration. The Zionist leadership of the newborn state chose the romanticized code-name Magic Carpet to describe the immigration from Yemen, and the biblical title Operation Ezra and Nehemiah – they were Jewish leaders who returned to Jerusalem from Babylon to build the Second Temple – for the exodus of the Iraqi Jews.

Read more: https://www.jcpa.org/jpsr/jpsr-beker-f05.htm