Lost Homelands, Imaginary Returns – The Exilic Literature Of Iranian And Iraqi Jews

When I first contemplated my participation in the “Moments of Silence” conference, I wondered to what extent the question of the Arab Jew /Middle Eastern Jew merits a discussion in the context of the Iran- Iraq War. After all, the war took place in an era when the majority of Jews had already departed from both countries, and it would seem of little relevance to their displaced lives. Yet, apart from the war’s direct impact on the lives of some Jews, a number of texts have engaged the war, addressing it from within the authors’ exilic geographies where the war was hardly visible. And, precisely because these texts were written in contexts of official silencing of the Iran-Iraq War, their engagement of the war is quite striking. For displaced authors in the United States, France, and Israel, the Iran-Iraq War became a kind of a return vehicle to lost homelands, allowing them to vicariously be part of the events of a simultaneously intimate and distant geography. Thus, despite their physical absence from Iraq and Iran, authors such as Nissim Rejwan, Sami Michael, Shimon Ballas, and Roya Hakakian actively participate in the multilingual spaces of Iranian and Iraqi exilic literature. Here I will focus on the textual role of war in the representation of multi-faceted identities, themselves shaped by the historical aftermath of wars, encapsulated in memoirs and novels about Iraq and Iran, and written in languages that document new stops and passages in the authors’ itineraries of belonging.

What does it mean, in other words, to write about Iran not in Farsi but in French, especially when the narrative unfolds largely in Iran and not in France? What is the significance of writing a Jewish Iranian memoir, set in Tehran, not in Farsi but in English? What are the implications of writing a novel about Iraq, not in Arabic, but in Hebrew, in relation to events that do not involve Iraqi Jews in Israel but rather take place in Iraq, events spanning the decades after most Jews had already departed en masse? How should we understand the representation of religious/ethnic minorities within the intersecting geographies of Iraq and Iran when the writing is exercised outside of the Iran-Iraq War geography in languages other than Arabic and Farsi? By conveying a sense of fragmentation and dislocation, the linguistic medium itself becomes both metonym and metaphor for a highly fraught relation to national and regional belonging. This chapter, then, concerns the tension, dissonance, and discord embedded in the deployment of a non-national language (Hebrew) and a non-regional language (English or French) to address events and the interlocutions about them that would normally unfold in Farsi and Arabic, but where French, English, and Hebrew stand in, as it were, for those languages. More broadly, the chapter also concerns the submerged connections between Jew and Muslim in and outside of the Middle East, as well as the cross-border “looking relations” between the spaces of the Middle East. Writing under the dystopic sign of war and violent dislocation, this exilic literature performs an exercise in ethnic, religious, and political relationality, pointing to a textual desire pregnant with historical potentialities.

The Linguistic Inscription of Exile

The linguistic medium itself, in these texts, reflexively highlights violent dislocations from the war zone. For the native speakers of Farsi and Arabic the writing in English, French, or Hebrew is itself a mode of exile, this time linguistic. At the same time if English (in the case of Roya Hakakian and Nissim Rejwan), French (Marjane Satrapi), and Hebrew (Sami Michael and Shimon Ballas) have also become their new symbolic home idioms. In these instances, the reader has to imagine the Farsi in and through the English and the French, or the Arabic in and through the Hebrew. Written in the new homeland, in an “alien” language, these memoirs and novels cannot fully escape the intertextual layers bequeathed by the old homeland language, whether through terms for cuisine, clothing, or state laws specifically associated with Iran and Iraq. The new home language, in such instances, becomes a disembodied vehicle where the lexicon of the old home is no longer fluently translated into the language of the new home—as though the linguistic “cover” is lifted. In this sense, the dislocated memoir or novel always-already involves a tension between the diegetic world of the text and the language of an “other” world that mediates the diegetic world.

Such exilic memoirs and novels are embedded in a structural paradox that reflexively evokes the author’s displacement in the wake of war. The dissonance, however, becomes accentuated when the “cover language” belongs to an “enemy country,” i.e., Israel/Hebrew, or United States/English. The untranslated Farsi or Arabic appears in the linguistic zone of English or Hebrew to relate not merely an exilic narrative, but a meta-narrative of exilic literature caught in-between warring geographies.

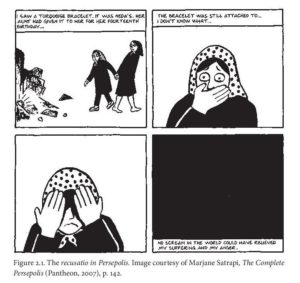

Figure 2.1. The recusatio in Persepolis. Image courtesy of Marjane Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis (Pantheon, 2007), p. 142.

Roya Hakakian’s Journey from the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis both tell a coming-of-age story set during the period of the Iranian Revolution, partially against the backdrop of the Iran-Iraq War. Written by an Iranian of Muslim background (Satrapi) and by an Iranian of Jewish background (Hakakian), both memoirs are simultaneously marked by traumatic memories as well as by longing for the departed city—Tehran. Although the Jewish theme forms a minor element in Persepolis, Satrapi’s graphic memoir does stage a meaningful moment for the Muslim protagonist in relation to her Jewish friend, Neda Baba-Levy. More specifically, it treats a moment during the Iran-Iraq War when Iraqi scud missiles are raining down on Tehran, and where neighborhood houses are reduced to rubble, including the house of the Baba-Levy family. While forming only a very brief reference in the film adaptation, the chapter in the memoir, entitled “The Shabbat,” occupies a significant place in the narrative. Marjane goes out to shop and hears a falling bomb. She runs back home and sees that the houses at the end of her street are severely damaged. When her mother emerges from their home, Marjane realizes that while her own house is not damaged, Neda’s is. At that moment, Marjane hopes that Neda is not home, but soon she remembers that it is the Shabbat. As her mother pulls Marjane away from the wreckage, she notices Neda’s turquoise bracelet. Throughout her graphic novel, Satrapi does display “graphic” images, showing, for example, the torture of her beloved uncle by the Shah’s agents and then by the Islamicist revolutionaries who later execute him. Here, however, the Neda incident triggers a refusal to show what is being expressed in words. After the destruction, Satrapi writes: “I saw a turquoise bracelet. It was Neda’s. Her aunt had given it to her for her fourteenth birthday. The bracelet was still attached to . . . I do not know what..” The image illustrates the hand of little Marjane covering her mouth. In the next panel, she covers her eyes, but there is no caption. The following final panel has a black image with the caption: “No scream in the world could have relieved my suffering and my anger.”[i]

Of special interest here is precisely the refusal to show, a device referred to in the field of rhetoric as recusatio, i.e., the refusal to speak or mention something while still hinting at it in such a way as to call up the image of exactly what is being denied. In Persepolis it also constitutes the refusal to show something iconically, in a medium—the graphic memoir—essentially premised, by its very definition, on images as well as words. Marjane recognizes the bracelet, but nothing reminiscent of her friend’s hand, while her own hand serves to hide her mouth, muffling a possible scream. In intertextual terms, this image recalls an iconic painting in art history, Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

While the expressionistic painting has the face of a woman taken over by a large screaming mouth, here, Persepolis has the mouth covered; it is a moment of silencing the scream. Satrapi represses—not only visually but also verbally—the words that might provide the context for the image, i.e., what Roland Barthes calls the “anchorage” or the linguistic message or caption that disciplines and channels and the polysemy or “many-meaningedness” of the image.[ii] In this case, the caption also reflects a recusatio, in that no scream could express what she is seeing and feeling. As a result, there is a double silence, the verbal silence and the visual silence implied by the hand on the mouth, and then by the hands on the eyes culminating in the black frame image. The final black panel conveys Marjane’s subjective point of view of not seeing, blinded as it were by the horrifying spectacle of war.

The World Today With Tariq Ali – Jewish Arabs And Cultural Cleansing

This week Tariq speaks to New York University scholar Ella Shohat about the history of Jewish people in the Middle East and North Africa, using her Baghdadi heritage as a starting point. Ella tackles the dominant, Western narrative on Jewishness, asserting that Jewish history, culture and opinion aren’t monolithic. Arab Jews, in particular, face the dichotomy of being considered both of the East and of the West – or, as Edward Said described it, being both Oriental and Orientalist.

Music in this video

Listen ad-free with YouTube Premium

Song – Shostakovich : String Quartet No.9 in E flat major Op.117 : III Allegretto

Artist – Brodsky Quartet

Album – Shostakovich : String Quartet No.9 in E flat major Op.117 : III Allegretto

Licensed to YouTube by WMG (on behalf of Teldec Classics International), and 5 Music Rights Societies

Song – Desert Life

Artist – Terry Devine-King

Album – ANW1181 – Editor’s Series – Middle East 3

Licensed to YouTube by Audio Network (on behalf of Audio Network plc); Audio Network (music publishing), and 6 Music Rights Societies

The Art Of Cooking – Hummus With Minced Meat

Hummus in Israel can be comparable to Pizza for Italians!

Hummus in Israel can be comparable to Pizza for Italians!

Normally the Hummus can be enjoyed plain or with some extra.

One day in Israel me and my dad visited Caesarea as a couple of tourists, and to our surprise we tumbled upon this Hummus dish topped with warmly spiced minced meat.

That moment left a strong impact on us and I have been making it ever since. The smooth texture of the Hummus combined with the savory bites of the minced meat creates a balanced taste at the moment you scoop as much as you can with a small piece of pita bread.

Trust me, this is the way to eat Hummus, scooping as much as you can with a small piece of pita bread – but do not get it on your fingers, there’s a limit!

Hummus Ingredients:

1 Large Can Chickpeas

Tahini (a paste made from sesame seeds)

2 Cloves of garlic

Lemon juice

Olive oil

Coldwater

Salt

Ingredients for the minced meat:

200-gram Minced meat (you can choose either lamb or beef)

2 Cloves of garlic

Paprika powder

Cumin powder

Salt & Pepper

Cooking oil

Toppings:

Olive oil

Pine Nuts

Fresh Parsley

Making the Hummus:

Inside a blender add the chickpeas, two tablespoons of tahini with the garlic, a pinch of salt, a squirt of lemon juice, and a drizzle of olive oil.

Now it is all about finding the perfect texture and flavor that you want! Keep tasting by adding a small amount of cold water to make the texture smoother.

Add more salt if it tastes too bland, as well as lemon juice if you want to put more zing into it!

There are many types of Hummus out there – however, it is up to you to balance the ingredients to become a favorite of your own taste!

Making the minced meat:

In a cold frypan add the minced meat with a bit of cooking oil, turn on the heat to medium-high and start breaking the meat apart, make sure you don’t keep big lumps. Once the minced meat is almost cooked through, add the minced garlic and all the spices (a teaspoon of cumin and a teaspoon of paprika, as well as, a pinch of salt and pepper). Keep stirring until all the minced meat is covered with the spices, that is until it turns brown and slightly sticky!

Serving:

Place the Hummus in a plate with a dent in the middle, then put the hot minced meat on top!

Top with pine nuts and fresh parsley and a drizzle of olive oil, you can also add some paprika powder on top.

Serve with pita bread, and of course, you may add some raw onion slices, boiled eggs, and pickled spicy peppers.

This is not the most traditional way to eat Hummus, but please give it a try. So, to go back to the comparison between Hummus and pizza, at the end the toppings are up to you.

However, if you want to make a Hawaiian Hummus go for it, but please let me know how this worked out……

My Arabic is Mute & Not to be afraid to say the word nostalgia

My Arabic is Mute

Strangled in the throat

Cursing itself

Without uttering a word

Sleeping in the suffocating air

Of the shelters of my soul

Hiding

From family members

Behind the shutters of the Hebrew.

And my Hebrew erupts

Running around between rooms

And the neighbors’ porches

Sounding her voice in public

Prophesizing the coming of God

And bulldozers

and then she settles in the living room

Thinking herself

Openly on the edge of her skin

Hidden between the pages of her flesh

one moment naked and the next dressed

She almost makes herself disappear

In the armchair

Asking for her heart’s forgiveness.

My Arabic is scared

quitely impersonates Hebrew

Whispering to friends

With every knock on her gates:

“Ahalan, ahalan, welcome”.

And in front of every passing policeman

And she pulls out her ID card

for every cop on the street

pointing out the protective clause:

“Ana min al-yahud, ana min al-yahud,

I’m a Jew, I’m a Jew”.

And my Hebrew is deaf

Sometimes so very deaf.

Not to be afraid to say the word nostalgia

Not to be afraid to say

The word nostalgia

Not to be afraid

To feel longing

Not to be afraid to say

I have a past

Placed in a box

Of locked-up memory

Not to be afraid

To buy myself some keys

To press my eyes to keyholes

Until it all opens

Until I can steal a glance

Into me

Not to be afraid to say

I’m a forgetful man

But I have a memory

That wouldn’t forget me.

Translated by Dimi Reider

Kunstmuseum Den Haag – Joseph Sassoon Semah – 31 oktober 2020 t/m 21 maart 2021

Joseph Sassoon Semah – On Friendship… 31 October 2020 – 19 September 2021

Exile, hospitality and friendship are key themes in the work of Joseph Sassoon Semah (b. 1948, Baghdad). In 1950 he and his parents were forced to leave Iraq to Israel, and Joseph eventually arrived in Amsterdam in 1981, via London, Berlin and Paris. On Friendship… will for the first time bring together 36 architectural models of houses, a synagogue, schools and cultural buildings made by Sassoon Semah that refer to the liberal Jewish culture of his Babylonian ancestors – a culture which, he says, barely exists except in memory now.

86 drawings and wall-mounted objects refer to the old culture and to exile. These works are part of his research project On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) III – The Third GaLUT: Baghdad, Jerusalem, Amsterdam. Referring to his own GaLUT (Hebrew for exile), these are the three cities with a reputation for tolerance where Sassoon Semah was made to feel welcome. Now he himself will act as host and friend, sharing his original culture. By way of a personal welcome, the triptych Joseph / YOSeF / Yusuf will be displayed beside one of the entrances to the exhibition in Kunstmuseum Den Haag’s Projects Gallery. The triptych is a kind of self-portrait featuring the artist’s name in Dutch, Hebrew and Arabic, along with a godwit (the national bird of the Netherlands), a hoopoe (the national bird of Israel) and a chukar partridge (the national bird of Iraq).

The work of Sassoon Semah allows plenty of scope for critical reflection on identity, history and tradition, and is part of the artist’s long exploration of the relationship between Judaism and Christianity as sources of western art and culture, and of politics. The aspirations of his grandfather, the Chief Rabbi of Baghdad, to promote dialogue between different religions and world views, resonates in everything he makes. One of the display cases will for example contain the prayer shawl (Tallit) that belonged to his grandfather, who refused to leave Baghdad during the first forced deportation, probably because to him Baghdad was already a place of exile, but above all because Iraq was his homeland. One of the wooden architectural models, a bronze version of which with rams’ horns will also be shown, is based on his synagogue, the Meir Taweig synagogue in Baghdad, which still exists but is no longer in use.

Lost paradise

Drawings of human skulls and the skulls of animals native to Iraq – 86 of them, the age at which Sassoon Semah’s grandfather died—also symbolise the lost paradise: the straight lines symbolising the street plan of the destroyed Jewish quarter, the yarn referring to measuring and territory, the sewing itself to textile as a carrier of information. A typewriter with Hebrew script and sand from Jerusalem on a steel Tefillin refer to the second place of exile, that of Sassoon Semah’s father, a leading lawyer in Israel. Joseph has reworked the book in the display case, the Talmud Bavli Tractate Pesachiem YaKNeHa’Z. His additions to the typography refer to his concept of architecture in exile. The abstract forms reference Mondrian, De Stijl and other abstract art of the West, the third place of exile. And so, in a metaphorical sense, On Friendship… is an ode to a lost culture, and at the same time an invitation to a dialogue about these different cultures.

Publication

New English-language publication ‘Joseph Sassoon Semah: On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) III – The Third GaLUT: Baghdad, Jerusalem, Amsterdam’ – published at the end of October, available in the museum shop. 264 pages, ISBN 978 90 361 0601 65, design and layout by Geert Schriever (artlifelove) Amsterdam, edited by: Linda Bouws and Joseph Sassoon Semah, € 39.95.

Nederlands:

Centrale thema’s in het werk van Joseph Sassoon Semah (1948, Bagdad) zijn ballingschap en gastvrijheid. Zelf wordt hij in 1950 samen met zijn ouders gedwongen te vertrekken uit Irak naar Israël en komt via Londen, Parijs en Berlijn in Amsterdam terecht. In de tentoonstelling brengt hij onder meer 36 architecturale modellen bijeen van huizen, een synagoog, school- en cultuurgebouwen die refereren aan de joods-liberale cultuur van zijn Babylonische voorouders, een cultuur die volgens hem buiten de herinnering amper nog bestaat.

Het werk van Sassoon Semah laat volop ruimte voor kritische reflectie op identiteit, geschiedenis en traditie, en maakt deel uit van een langdurig onderzoek van de kunstenaar naar de relatie tussen het jodendom en het christendom als bronnen van de westerse kunst- en cultuurgeschiedenis. In alles resoneert het streven van zijn grootvader, de opperrabbijn van Bagdad, om de dialoog te bevorderen tussen verschillende religies en wereldbeelden.

Zie: https://www.kunstmuseum.nl/nl/tentoonstellingen/joseph-sassoon-semah

Zie ook: https://vimeo.com/484103296/1f2e571ca3

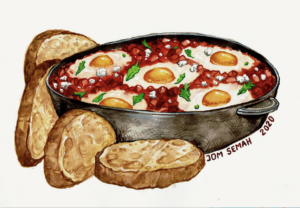

The Art Of Cooking – Shakshuka

Many dishes are unavoidable in the Middle East, and yet every country has its own version.

Many dishes are unavoidable in the Middle East, and yet every country has its own version.

One of those dishes is Shakshuka!

A savory tomato sauce with an egg cooked on top of it, and it tastes great at any moment of the day.

Because first of all, it is such an old dish which can be found all over North Africa and the Middle East, and secondly, there are so many different ways to make it.

I like to add eggplant, simply because I love it, and yet at the same time, the eggplant helps to make the Shakshuka a bit more savory.

But please feel free to try out different ingredients/toppings and spices when you are making your own Shakshuka!

Ingredients:

1 Eggplant

Eggs

Large onion

Garlic

1 Cayenne pepper

1 Red paprika

2 Canned diced tomatoes

Olive oil (for cooking)

Salt

Pepper

Paprika powder

Cumin powder

Turmeric Powder

Feta cheese or any good alternative white cheese for topping

Fresh parsley

Cooking Shakshuka:

First of all begin with dicing of the eggplant into small chunks, then cook them with oil in a deep skillet until golden brown.

Meanwhile, dice the onion/garlic/paprika and cayenne pepper (remove the seeds if you do not like it too spicy).

When the eggplant is soft and cooked through – make sure there is enough oil in the skillet – add the onions and cook the mixture until translucent, at this moment you can add the garlic, the paprika, and the cayenne.

By now you can add the seasoning, a pinch of salt and pepper, a teaspoon of paprika, a teaspoon of turmeric, and cumin (you can add a pinch of dried chili or ground cayenne pepper if you like it extra spicy!).

When all the seasoning is mixed well with the vegetables add the canned diced tomatoes and let it simmer for 15 minutes. You can add a splash of water when the mixture becomes too dry.

By this time when the tomato mixture is cooking, the sauce becomes thicker; at this moment one should make holes in the sauce for the eggs.

An easy way to place the egg into the Shakshuka is by cracking the egg into a bowl first.

So, when all the eggs are on top of the sauce put a lid on, let it simmers for a couple of minutes until the eggs are cooked to your liking.

Please note, when you turn off the fire let the eggs cook a bit longer in the hot tomato sauce before served.

Garnish with fresh parsley, crumbled feta cheese, and a drizzle of extra virgin olive oil.

Eat with any type of bread, even with toasted bread, that is as long as you can soak up all that sauce!