IIDE Proceedings 2011 ~ Vol.2 ~ Down-To-Earth Issues In (Mandatory) Information System Use: Part II – Approach To Understand And Reveal Hidden Issues

No comments yet Abstract:

Abstract:

This paper proposes a new way of approaching mandatory information system use (MISU) to understand and reveal hidden issues which are meaningful in everyday life of system users. We call these Down-to-Earth (DTE) issues, and they are better at providing guidance for information system evaluation. Case study research in using information system was conducted on system users to demonstrate how DTE issues are formed. Unstructured interview was used as the main data collection method. Results show that the new way helps to understand in depth and reveal the hidden issues, which makes this approach more practical for system evaluation.

Keywords:

Down-To-Earth, Mandatory Use, Dooyeweerd’s aspects

1. Introduction

Information systems (IS) used in the organisation are seen to provide benefits in terms of increased productivity, and improved strategic positions and daily operations (Yoon & Guimaraes, 1995). Such benefits though are at the organisational level, whereas at the individual level, the system can provide benefit in helping individuals to complete job tasks and obtain evidence for decision making. To evaluate the benefits especially to individual system users it is important to look for meaningful issues in everyday life working experience (Basden, 2008).

Basden and Ahmad (2011) emphasize `meaningful issues’ in mandatory IS use (MISU), describing them as Down-to-Earth (DTE) issues. DTE issues are sensible and practical for system evaluation because they are specific in their context and easily understood by system users. Current debate in the field discussed the contrast between DTE issues and extant issues. Examples of extant issues are perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness (Davis, 1989; Shih & Huang, 2009), IS quality (Lin, 2010; Linders, 2006), management support (Chang, et al., 2010; Lin, 2010; Rouibah, et al., 2009; Shih & Huang, 2009) or computer self-efficacy (Adamson & Shine, 2003; Linders, 2006; Singletary, et al., 2002). Basden and Ahmad (2011) argue that, in providing guidance to practical evaluation of IS use, such extant issues are unhelpful in several ways: unhelpful level, unhelpful connotation, unhelpful abstraction, unhelpful combination, as well as missing many important issues.

‘Unhelpful level’ refers to issues that might be of interest to senior management, IS developers or researchers but have little direct meaning to users. Here, ‘users’ not only refer to direct users. They include all those involved in tasks and activities that in some way relate to the IS in use. Users are seen as social actors (Lamb & Kling, 2003), not just as individuals. ‘Unhelpful connotation’, on the other hand, refers to unspoken meaning imposed on concepts because of the cultural assumptions of researchers which differ from the assumptions made by users. ‘Unhelpful abstraction’ refers to issues that are too general, such as ‘risk’. Next, ‘unhelpful combination’ refers to issues that combine several important meanings that could and should be separated. Lastly, ‘missing’ issues refer to those that happen to have been overlooked by extant discourse because it has not yet recognised their importance even though they have been important to users.

Basden and Ahmad (2011) suggest that, instead of trying to understand IS use in such terms as above, we should do so in DTE terms. Unfortunately, DTE terms cannot be defined precisely since many of them are intuitive, but Basden and Ahmad (2011) illustrate them by using Wenger’s (1999) passage in vignette of a day in the life of Ariel, a data entry clerk. An example of Wenger’s passage,

“She enters first the type of service, then the name of the service provider, which leads her into the providers file: there she makes sure she checks that the provider’s address is correct since the insured has ‘assigned’ the benefits to be disbursed directly to the doctor. … Since the patient went to such a ‘preferred’ doctor, Ariel must remember to increase the rate of reimbursement from 80% to 85%.” (pages 22-3).

Analysis of this using extant literature might focus on perceived ease of use (Davis, 1989) or IS quality (Linders, 2006) for example, whereas to Ariel the important DTE issue is making sure she remembers something so that appropriate payment is made, and ease of use or IS quality merely help or hinder her in this. Basden and Ahmad (2011) suggest that the issues may be understood by reference to Dooyeweerd (1955), to a suite of fifteen aspects that are meaningful in everyday activities of system users and would suggest that the real issue of appropriateness is of the juridical aspect. However, Basden and Ahmad (2011) do not show how they obtain DTE issues in practical analysis. This is the purpose of this paper. The aim is to propose and discuss a new way to understand and reveal DTE issues in mandatory information system use (MISU) by system users.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: the research background covers how the extant constructs were formed and how they were analysed, research method used, attempts to use Dooyeweerd’s aspects, the findings and lastly the discussions and conclusions.

2. Research background

One way to overcome the unhelpfulness of extant issues is to try to reconceptualise them. Barki (2008) suggests four ways to do this, and Joneidy and Basden (2011) attempt that using Dooyeweerd’s aspects to reconceptualize extant constructs. This paper explores a different approach: to bypass extant issues altogether and find a method to analyse situations of IS use directly in a way that surfaces the DTE issues. To prepare for this requires understanding of qualitative research and why extant issues are unhelpful.

2.1 Review how the main contructs were formed

The extant issues (constructs) used in research by current researchers do not take into consideration the everyday working life experience of system users (Basden & Ahmad, 2011). Examples of studies not using issues based on what IS users think is important include those carried out by Chang, et al. (2010), Lin (2010), Shih and Huang (2009), Rouibah, et al. (2009) who use survey to test hypotheses about the relationship of issues towards IS usage. However, their issues were chosen issues by the researchers rather than being meaningful to users. In many cases, the chosen issues are based on previous research rather than on why such issues are important from the perspectives of users. For example, Yoon and Guimaraes (1995) emphasise the issue of management support but this has already been emphasized as important by other authors. Previous research also included issues used by Davis (1989) to develop his Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness.

The original source of issues is itself usually using prior theory. This is shown in the following examples:

* Constructs in Venkatesh et al.’s (2003) Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use Technology (UTAUT) model come from eight theoretical models, including Davis’ (1989) Technology Acceptance Model (TAM).

* Intention to Use construct of TAM comes from Fishbein & Ajzen’s (1975) Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which comes from psychological theory.

* The Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use constructs, important as determinants of user behaviour as several theories indicate, include behavioural decision theory, self efficacy theory and adoption of innovation (Davis, 1989).

* The self efficacy in the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) comes from theory of human behaviour (Compeau & Higgins, 1995).

Constructs that are based on theory are limited for two reasons. One is that theory limits itself to one or a very narrow range of aspects (ways in which reality is meaningful). The other is, as Clouser (1991, p. 51) explains, “once theories are formulated, tested and accepted by experts, they become the most authoritative standard for judging the truth of whatever they are about”, which further restricts research to the narrow range of aspects. Constructs based on such a narrow view are not adequate for revealing DTE issues, because DTE issues cover a very wide range of aspects of IS use and in trying to reveal them researchers should not be restricted by what is currently deemed authoritative. Instead, to reveal DTE issues requires a more intuitive approach, but one that is systematic.

Because extant issues are narrower in their scope than everyday life is, those who work with them find they must always keep adding other significant issues (e.g. ‘external variables’ added to Davis’ (1986) TAM) to enhance the explanation of the actual usage (Shih & Huang, 2009). A Meta analysis of the TAM by Yousafzai et al. (2007) showed about 70 constructs have been suggested to be included in the study of using TAM. With 70 constructs, the model becomes unwieldy and many of them overlap with others (Ahmad & Basden, 2008; Joneidy & Basden 2011).

2.2 Qualitative research and interviews

Quantitative methods such as survey with statistical analysis have been well established and widely used in research on issues relating to IS use (Trauth, 2001). But the quantitative ways of doing research only suit situations where sample size is large in order to generalize results to a large population. By contrast qualitative research focuses on a particular situation in detail (Myers, 2009, p. 9). Thus, investigation of human experience can best be done using qualitative methods (Polkinghorne, 2005, p. 2).

Myers (2009) states that, “If there is one thing which distinguishes humans from the natural world, it is our ability to talk! Qualitative research methods are designed to help researchers understand people and the social and cultural contexts within which they live”. This study is qualitative in its nature and the empirical data was gathered based on unstructured interviews with direct users rather than those at management level. This is because the majority at management level is not using IT frequently (Mahmood, et al., 2001) but indirectly via IT output produced by other people (Ang, et al., 2001).

The interview (or inter-view) is an exchange of views between two people talking about the common interest, one of whom is in the role of researcher (Kvale, 1996). Interviews allow the researcher to obtain better understanding of users’ everyday experience since people will have a variety of opinions, thinking and the rationale as to why they did certain things (Myers, 2009). They help to obtain the interviewee’s views and experiences in his or her own terms (Kaplan & Maxwell, 1994). Furthermore, a lot of data can be obtained from different angles and different types of questions can be answered by interviewees since different people will give different views (Myers, 2009). Also, through interview the researcher can approach the interviewees face to face and can clarify issues that are not clearly understood.

Open interviews encourage two-way communications rather than only one way as when questionnaires or structured interviews were used. Conversation can `give a feel’ (Watson, 1987, p. 53) on situations being studied. Conversation with system users, who directly experience use of the system, is the best way to gain understanding of everyday life activities of individual user. “Experience has a vertical depth, and methods of data gathering, such as short-answer questionnaires with Likert scales that only gather surface information, are inadequate to capture the richness and fullness of an experience” (Polkinghorne, 2005, p. 2). For these reasons, interviews are used in this study in order to uncover and understand the DTE issues of MISU, with questions designed to open up the users’ everyday experiences.

2.3 Interpretive and qualitative analysis

There is a wide range of literature that documents the procedures associated with analyzing qualitative data. Many of these are associated with specific approaches or traditions such as grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990), narrative analysis (Alvarez &Urla, 2002) and phenomenology (Wojnar & Swanson, 2007). However, DTE issues present particular challenges.

One of these is multiple meaning. Klein & Myers (1999) publish principles for interpretive IS research. Principle number six states the importance of multiple interpretations: “the different interpretations among the participants as are expressed in multiple narratives or story of the same sequence of events under study”. For DTE issues, however, it is not enough simply to collect multiple narratives because what people say does not always express all that is meaningful, and there are meanings hidden behind what they say that needs to be brought out. For example, when interviewing users on the issue of `support from supervisor’, the replies received might express complaints (or praises) but these might be limited to those that happen to be going round the situation of system use, while other issues related to this are left unspoken for various reasons. This is illustrated by Holden (2010), based on interviewees’ feedback such as “I can very quickly get the nuggets of information that I need, versus … looking around and asking the personnel on the floor, `Where is the old chart?’.” The researcher interpreted the statement as “Immediate access to information to speed up work”, but many issues remained hidden, such as relationships in the workplace and why nuggets of information are useful.

Current ways of conducting data analysis are through indentifying themes, formed directly from what is said by the interviewee, even though the issues that emerge at the end of the process might be abstractions from them. Jain and Ogden (1999, p. 1597) explain a typical process.

The interviews were audio taped and transcribed. The transcripts were read several times to identify themes and categories as recommended by Miles and Huberman (1994). In particular, all the transcripts were read by AJ and a subsample was read by JO. After discussion a coding frame was developed and the transcripts coded by AJ. If new codes emerged the coding frame was changed and the transcripts were reread according to the new structure. This process was used to develop categories, which were then conceptualised into broad themes after further discussion. The themes were categorised into three stages: initial impact, conflict, and resolution.

One problem with this kind of process, combining themes to make up sub-themes, is that it does not help to understand the multiple meanings of what have been said by interviewer. So a method of analysis is needed that is able not only to encourage the IS users to express their concerns openly but also to find the multiple meanings hidden behind what they actually say.

3. Research methods

This research seeks to gather as many user’s DTE experience as possible. Ten direct users participated in this study, in particular those who used the system directly for job completion and have been working with the organisation since the system was implemented in 2007. They were selected from among the middle and lower level staff since they used the system everyday. Managerial staff only used the system once in a while when they need it for reporting purpose.

3.1.The interviews

Interviews were conducted on these direct system users in a public service organisation under Local Enforcement Agency responsible for ensuring development and services to the community living within their authority. The type of system involved in this study is a system that captured the business process activities. Users have no choice but use the system to complete their job tasks (i.e. mandatory IS). Appendix 1 contains a brief description of the systems they used known as Local Government Information System (LoGIns), Financial Information System (FINIS) and Assessment and Valuation Information System (AVIS).

The interview must allow the researcher to obtain ideas and feelings from users and enable both parties to discuss meaningful issues. The types of questions asked during the interviews were rather unstructured, more so in the full study than in the pilot study. The type of questions put to interviewees is important, so that they will not just say `Yes’ or `No’ but feel encouraged and stimulated to open up about what they find meaningful to them in their everyday work.

3.2 The pilot study

A pilot study was conducted to help decide who should be interviewed, how much access to the organisations the researcher was able to gain and to prepare the schedule (Avison& Myers, 2005). It also helped the researcher to expose herself to the organisations, enabled the research design to be reviewed, and to create a good relationship between those who will be involved in the study. The impression during first meeting is important to convince interviewees what benefits they can gain for their cooperation and assure them that there will be no effect if they refuse to cooperate. The pilot study also exposed the researcher to the types of system used in the organisation. The data collection aim was to get the overall idea of what sort of information the researcher can obtain and what types of questions are useful. The people involved during interview were one IT Officer and three system users. Three main things were learned during the pilot study, namely

(1) change for the full study,

(2) informing the process, and

(3) contributing to the results of the research.

First, most of the questions asked were related to the user interface and system performance and related to input and output processes. Basden (2008) calls this human computer interaction (HCI). And, how system usage affected their lives Basden refers to this as human living with computers (HLC). The latter description is considered more important in IS use. Second, the interview sessions were conducted in front of users’ computers while the interviewees continued doing their job, so full concentration was not possible during the interview sessions. There were interruptions from other staff, as well. Third, the questions were explicitly designed to try to cover all of Dooyeweerd’s aspects of the IS use, but this proved to be a constrain rather than stimulate the conversation, contrary to by Kane’s (2006) finding; see below.

3.3 The main study

The main study changed the scope of these three. Questions focused more on HLC matters, such as how family issues affected their work flow and how they handled personal matters, if any. Each interview session was conducted in a separate area or room so that the interviewee remained focused on matters discussed with the researcher as they share their experience about using the system. Also, this helped avoid any influence from either their superior or colleagues that might affect what the users would like to share. Except as discussed below, Dooyeweerd’s aspects were hardly used during the interview process, but kept at the back of the researcher’s mind only to ensure aspects were not overlooked by the researcher.

The interviewees’ opinions are important to clarify their experiential life as “it is a life-world where they lived, felt, undergone, made sense of, and accomplished” (Schwandt, 2001, p. 84). Therefore, in both stages of data collection, the researcher encouraged the interviewees to express their own opinion that reflected their experience in the past. This also helped in not losing the richness in explanation and interpretation.

3.4 The transcription process

The interviews were conducted in Malay. Translation process was carried out for the transcriptions to be translated to English language directly from the tape recordings. The sentences were translated by sentences. Example 1 shows how the translation process was done. Each sentence was translated from Malay to English.

Example 1 – Malay language:

Question: Sudah berapa lama menggunakan sistem?

1. Guna system baru sebulan. Sebelum bahagian lesen saya kerja di bahagian penilaian.

2. Saya guna system LoGInS untuk semua berkaitan dengan permohonan lesen. Masa itu saya guna AVIS.

3. Sebelum kunci masuk, kena pastikan borang cukup dan dilampirkan sekali serta di sahkan.

4. Juga RM10 sudah dibayar oleh pemohon sebagai servis perkhidmatan. Saya tengok pada resit.

5. Kalau yang lebih RM10, ianya campur sekali dengan jenis lesen lain. Contoh untuk lesen sementara.

6. Bagi yang permohonan baru saya kena buka fail. Lesen ini hanya untuk setahun. Setiap tahun kena mohon.

7. Selain kerja ini, saya juga buat kerja lain dari arahan boss.

English language – Question: How long have you been using the system?

1. Used it for about one month. Before working with licence department I worked at valuation department.

2. I use LoGInS for everything related to business license application. That time I used AVIS.

3. Before keying-in into system, must ensure enough documents and attached together and certified, as well.

4. Also RM10 processing fees have been paid by applicants for services rendered. I refer to the receipt.

5. Ones which exceed RM10, are combined with other types of licences. Such as for temporary license.

6. For new application I need to open a file. This license is only for one year. Every year will have to apply

7. Other than this task, I also do other work instructed by my boss.

4. Attempts to use Dooyeweerd’s aspect during interviews and analysis

This exploratory research aims to apply Dooyeweerd’s fifteen aspects to gain a deeper understanding of users’ everyday life experience and reveal meaningful issues in their use of information system (Basden, 2008). Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects is explained in Basden & Ahmad (2011). The term ‘aspects describes “a way in which a thing may be viewed or regarded; interpretation” (Dictionary.com). The word ‘thing’ in this research refers to users’ everyday life experience in using information system.

This section will cover how aspects were used to help in obtaining DTE issues. Researchers cannot assume that what users verbally say is relevant and what they did not say is irrelevant because users might overlook some important issues. There were two stages: interview and analysis. Dooyeweerd’s aspects were mostly used during the analysis and as background guidance only during most interviews.

4.1. Approaches during interviews

The interviews started with the researcher’s background and continued with explanation about the purpose of the interviews and links with the research. Then the researcher focused on user’s general background such as educational background, family background and the reasons for joining the organisation. This puts them at ease when sharing their experience. The researcher used four different tactics in the order shown below during the interview sessions to probe and discover meaningful issues in each individual user.

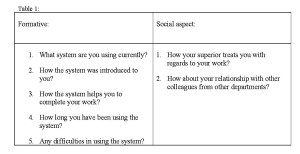

* First – developed questions based on Formative and Social aspects for the introduction part of the session.

* Second – showed a list of Dooyeweerd’s aspects.

* Third – approached the questions based on what is shared by interviewees, not based on aspects

* Fourth – applied Dooyeweerd’s aspects in the back of her mind after interviewees finished haring their experience on one issue to guide them to other issues if necessary.

These four tactics were used in combination with each other when the researcher conducted the interviews. They might be used in any sequence, though the first would always be first because the formative and social aspects provided useful introductory questions. The second tactic was soon abandoned when it became clear that it alarmed and constrained the interviewees.

The first tactic, using the formative and social aspects had as its main objective to open up a discussion for users to feel comfortable in sharing their experiences. Formative was used because it relates to interviewee’s task in using the system and to the system itself whereas social relates to roles and relationship between staff in the organisation studied. Table 1 shows the type of questions asked regarding each aspect. Most questions focused on job tasks because job task is the main aim and relates to system usage. Not all questions were asked of each interviewee, but they provided general guideline to the researcher to initiate the interview session.

The second tactic was to show a list of fifteen aspects to the interviewee. The researcher received negative response from the first interviewee who looked stunned and asked whether she needed to think of issues related to all the aspects. The researcher explained the aspects but the interviewee still refused to cooperate. Attempts to show the list of aspects during the interview was later abandoned.

In the third tactic the researcher did not approach the question based on aspects but based these on what had previously been shared by interviewees. As Ramachandran (2011) states, a general rule in discussion seems to be that “if you ask a good question, the answer should lead to additional interesting questions”. This leads to a situation where the researcher will pose further questions based on answers given earlier. As a result, this will further reveal other meaningful issues that the interviewees may not realise. This tactic also provides opportunities for extensive exposure to the mandatory IS use life-world (Nandhakumar & Jones, 1997). The researcher allowed the interviewee to voice out any new ideas, so the direction of discussion would sometimes change to track down a new issue given by the interviewee.

The first part of the question as shown in Example 2 below is related to the interviewee’s job tasks where he explained how his work started and what the outcome was. Once he prompted the word `public’, the researcher asked a question related to the public issue. At the end of the session, the researcher asked the interviewees if they had any other issues they want to discuss about system usage. This is to ensure that interviewees have nothing left in their mind that they want to share.

Example 2 – Question: Can you share with me your responsibilities related to the system?

Answer: (M5g) My work will start once clerk has done her part. With AVIS the work for Clerk becomes lesser but for me as technician there is more work to be done. What clerk needs to do is they will register the case through AVIS. Once it has been registered then I can proceed on my part to key-in all figures for calculation of tax assessment. Once AVIS calculates the tax assessment figures, I’ll forward to superior for approval before sending it to public for tax payment.

Question: How can the public make payment?

Answer: (M5h) If the public wants to make any payment, the counter service staff will login into AVIS to reconcile the figures. If they find the figures tally with the payment the counter service staff will process the payment.

(M5i) As you can see, AVIS is used by valuation department staff and also counter service staff. IT department has to limit the number of staff allowed to use AVIS at one time. Due to this, in some situation AVIS gets stuck and hangs while I’m still doing my work. At that point, I just have to wait since I cannot do anything. We have been facing this issue since 2007 and management needs more budget for IT investment so such problem does not occur again. Due to this we have to accept as what it is.

The fourth tactic was to ask questions based on any aspects that came to mind as significant. The knowledge of aspects was kept at the back of researcher’s mind rather than by showing the list to interviewees. During the fourth tactic, as Example 3 shows, the earlier conversation concerns issues of the interviewee doing a process of the application form. Then she mentioned, “do other task instructed by my boss”. This prompted the juridical aspect, to help in understanding whether the interviewee has been fairly treated by her boss giving tasks that had not been specifically mentioned in the job description. The explanation given shows that she has no problems doing other additional tasks given by her boss.

Example 3 – Question: In one day roughly how many forms did you receive?

Answer: (M6f) Not consistent, so far I received up to 20 new forms per day plus forms from previous applicants. Whatever I received in the morning I must make sure to complete it on the same day. However if I received it after 16:00 hours, I can complete it by tomorrow morning the latest. I also do other tasks instructed by my boss like preparing letter.

( Posted a question based on juridical aspect)

Question: In the licence department who else other than you does the same things especially keying-in information into the system?

Answer: (M6g) No one else. I’m the only one who will process the application for new license. Other colleagues will help if I’m on leave or on holiday. As I mentioned earlier not many forms to process so I can do it on my own. Sometimes it’s only 10 forms. So I think we don’t need more staff to do what I do currently. Normally I will walk to the counter and request the form so that my work will not be put on hold. If I wait for the counter service staff to pass it to me, they will normally do it around 10:00 hours or at 16:00 hours. For me it is too late to process the forms on the same day. No days without the forms. This will also keep me moving and I will not get bored, just sit at one place. During this time I can also chat with some of my colleagues just to say hi. You just imagine if I sit at my place from morning until the end of office hour surely I will feel bored and sleepy too.

4.2 Approach during analysis

Analysis is the final stage to hear the meaning of, understand and organise what has been said by interviewees. Analysis starts with the interpretation process of what interviewees said (Robson & Foster, 1989, p. 85). It is crucial to understand the meanings shared by interviewees, treating each interview as a unique situation, the researcher using their own intuition in responding to interviewee’s questions. In some cases, interviewees might have shared their `painful experiences’. Analysis can be exciting because of “continuing sense of discovery but can also be intimidating due to sheer amount of interview data that has to be understood” (Rubin & Rubin, 2004). The amount of data generated by qualitative methods is huge and the process of making sense out of pages related to interviews can be “overwhelming” (Patton, 1990).

Since this study is qualitative it dealt more with words than figures. Analysis consisted of two parts. Tesch (1990) was used as a guidance to develop an organising system for unstructured qualitative data from interview transcriptions and generate a list of issues under themes. These were then further analysed with reference to Dooyeweerd’s suite of fifteen aspects where the aspects helped find the DTE issues, especially those that were hidden.

In structuring the bulk of qualitative data Tesch (1990) was also used. He named the process of segmenting and categorizing data ‘de-contextualization’ and ‘re-contextualization’ (p. 115). All unstructured data of interviews that gave the same meaning were brought together to generate several themes of groups. The data was examined to understand what issues were discussed by interviewees and labeled (Patton, 1990). The following general steps were taken. Data transcriptions were read carefully to get the whole idea that had been shared by the interviewees and at the same time stating their main issues or topics.

* Once a set of interviews was finished, state all topics identified and continue with others.

* Any new topics revealed, update the list.

* Compiled groups from the sentences or passages that explain the same topic or issues.

* Formed groups.

Words uttered by interviewees make up the sentences to present a story. However, what has been said through words does not necessarily explain the real situation nor the reason why it is said. Words or sentences have `multiple meanings’ (Miles & Huberman, 1994). One type of multiple meaning was investigated by Austin as `Illocutionary act’: “uttering a sentence with a certain force.” Example: “I am going to do it” can be (can have the force of) a promise, a prediction, a threat, a warning and a statement of intention” (Searle, 1968). Therefore, analysis was not based only on the sentences but also on the need to understand the `multiple meaning’ of what is said by the system users and to uncover the semantic `behind’ the sentences explained by individuals.

This was achieved by using Dooyeweerd’s aspects. Each aspect is important in human activity in general, and thus in IS use, whether voluntary or mandatory. IS usage is seen by Dooyeweerd as human functioning in a number of aspects, each of which is a distinct sphere of meaning. These spheres of meaning make possible both the explicit meaning of the sentence and also its various illocutionary meanings. Hence, multiple meanings can be discovered and uncovered by reference to Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects.

When reading the passages, the researcher looked for words or sentences that are meaningful to interviewees and at the same time incorporated aspects starting from Biotic up to Pistic (see Basden & Ahmad 2001, this volume, for the aspects). The earlier aspects – Quantitative, Spatial, Kinematic and Physical aspect – were not analysed since they are related to pre-human functioning, where no feeling is involved. The main question asked when analysing the passages was: Which aspect or aspects are meaningful for this particular issue? This was asked again on passages. The aspects were considered one by one.

During the analysis process, the researcher’s imagination of the situation contributed to have a feel for what is happening. The imagination helps in two ways: By imagination, aspects help to find other issues and by imagination any prior experience the researcher might have helps to see how new aspects might be relevant. The first author had earlier been employed in situations of mandatory IS use similar to those being researched, and so could feel as though in the shoes of interviewee. She would ask a question like: If I were the interviewee, why would such issue be meaningful? And, in what way it is meaningful? Using the imagination, the researcher’s prior experience helped to understand the interviewee’s concerns on system usage issue.

In general, the kernel meaning of each aspect may be grasped with our intuition, rather than by theoretical thought (Basden, 2008): this recommends the aspects as a tool for use in analysis because both researcher and interviewee can intuitively understand them. This way, aspects helped to understand and reveal DTE issues in IS use in both interview and analysis. Some examples of findings follow.

5. Findings

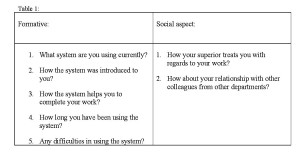

5.1 Identification of issues and groups from standard qualitative analysis

Table 2 shows the list of groups and issues identified from the interview transcription based on the general guideline of organising qualitative data by Tesch (1990). Table 2 not only includes IS use issues but also other related matters that might influence the way users used the system. If the researcher focuses on IS use matters only, there are circumstances in which other meaningful issues might have been overlooked, particularly issues that might be related to the way users use the IS. Examples include `dealing with public matters’ or `family commitment’. Public issue for example, does affect the user’s flow of work, sometimes. As the interviewee explained:

“I cannot really concentrate on my work because the public stand in-front of me. Sometimes to finish one file it takes up the whole morning lasting until lunch. Whatever the situation is we must entertain them. We did highlight to management to have one staff for license counter but the management did not approve it” (M6ak).

Dooyeweerd’s aspects were not used when groups were formed. This is because the meaningfulness of the groups listed in the table is life-world meaning that are built up from experience and other functioning in life.

5.2 Limitation in result form standard qualitative analysis

Some of the issues in Table 2 are already DTE issues, but many are not. As explained in the background of the study, extant qualitative analysis methods have limitations in revealing the hidden and multiple meanings of what has been said by interviewees. To overcome the limitation it was suggested that Dooyeweerd’s aspects be incorporated since human everyday activities are functioning in many aspects. Basden and Ahmad (2011) have explained the reason for using Dooyeweerd’s aspects to understand the meaningful issues in everyday experience of system users and give some justification for doing so.

Human life is seen as a complex, integrated functioning that can only be adequately explained by reference to all the aspects (Basden, 2002). This echoes Ozer and Yilmaz (2011) who state “to derive benefits from IT completely, it has to be discovered in all aspects”.

Dooyeweerd’s aspects are preferred to those of others for several reasons (Basden, 2001). Firstly, they have wider coverage since most aspects identified in the literature are a subset of the Dooyeweerd’s aspects, so Dooyeweerd helps to look for issues that have been overlooked. Secondly, Dooyeweerd’s set of aspects has been subjected to philosophical and historical scrutiny. Thirdly, Dooyeweerd himself spent a life’s work thinking about the aspects. However, Dooyeweerd (1955, Vol. II, page 556) made clear that any set of aspects, including his own, cannot be considered a final truth because separating them out depends on theoretical analysis; his set is only his best guess at the diversity of meaning.

Once groups had been compiled, Dooyeweerd’s aspects were incorporated to understand intuitively the everyday life activities of system users and to use aspects to discover and uncover deeper meaning on everyday issues. All groups were analysed by using the aspects. None of the groups were ignored because Dooyeweerd’s aspects help to reveal other issues in everyday life activities that interviewees themselves did not realise were meaningful that may be related to IS use. For example, `Family Commitment’ is not directly linked to system usage but if anything happens to the family, the system users are unable to focus on their work. Use of Dooyeweerd’s aspects generated the different perspective or angle to see how users deal with an issue like Family Commitment.

The next section will explain what had been found and how to employ Dooyeweerd’s aspects to understand multiple meanings and reveal hidden DTE issues.

5.3 Dooyeweerd’s aspects to understand and reveal DTE issues

It was found that aspects relate to issues generated by qualitative analysis in two main ways, each of which provides a different way of revealing DTE issues.

5.3.1 Aspect direct from issue/s

In some issues only one aspect was identified as being meaningful, and this aspect directly showed what is meaningful to the users. Such issues are already DTE, and no further analysis was done. For example:

| Code | Issues | Passages | Aspect/s |

| SU7 | Bored with system features | (M9a3) A bit bored because of the interface.(M12q) LoGInS is very old system, sometimes I get bored. As you can see it is not very colourful. LoGInS use white background and black colour for the wordings. | (SU7a) Aesthetic – unhappy with the system feature and feeling bored (direct form issue) |

Because users felt bored with the system features it gave the impression that interviewees felt unhappy with what they see and wished that the system could have better features instead. Boredom directly affects quality of MISU. The aspect that helps to understand the above situation is the ‘aesthetic’ since its kernel is style, enjoyment, interestingness and harmony.

Identifying which aspect makes the issue meaningful to users has two benefits. One is that it explains more clearly what it is about the issue that is meaningful to users. The other is that reference to its main aspect can help raise questions that can deepen further exploration. For example, if we were to ask how boredom with system features might be overcome, and we did not make reference to the aesthetic aspect, we would be tempted to add flashy colours (since colour is mentioned), but it is likely this would not solve the problem except for a few days. However, if we recognise that aesthetics is not just of user interfaces but of human living, and it concerns not just style but also with harmony and interest and enjoyment, then we might pose the question of whether use of the IS is harmonious with the rest of the users’ lives or not, and whether there is enjoyment or interest in the whole use, and see whether this is the cause of apparent boredom. Thus, though the issues found by qualitative analysis sometimes can be considered as DTE issues, aspects can deepen our understanding of them.

5.3.2 Aspects discover DTE issues from passages

The second way aspects are used is to understand the passage based on words clearly mentioned by interviewees. The word(s) were identified directly from passages.

| Code | Issues | Passages | Aspect/s |

| SU2 | Password | (M2g) I just need to use command to extract the information. What I must remember is my password and press ‘ENTER’ few times and that’s it.(M2g) I have to logout once I’m not using the system. This is important to protect our password. If other staffs use our password, we might be caught. But sometimes I forget, too. (M11h) Password also bring difficulties to me, since we are using different system, surely we need different password. If too many passwords, we will forget. Even if we write somewhere at the end we misplace. | (SU2a) Lingual – password to login into system(SU2b)Juridical – users are responsible for protecting the password from wrong doing by unauthorised users because if not users themselves will be caught

(SU2c) Analytical – users need to think and choose which password is meant for information access

(SUd) Sensory – users need to remember the password since they are using more than one system |

‘Password’, as shown in the table above is one example of the issues to users. Its most obvious aspect is the lingual, since users can only login into the system by using symbols either alphabets or numbers. Though perhaps useful to academic and technical literature, `password’, has limitations when considering DTE issues because this does not explain why it is a concern to users. The issue of password carries hidden connotations and might have multiple meanings of why the password is important.

To understand this further, the passages were analysed to understand the multiple meanings of issues, which are often hidden. Each sentence about password mentions one or more things that are of concern, and highlighting the aspect that makes that concern meaningful can bring it to light as a DTE issue. The juridical aspect brings to light the situation where users need to make sure the password is protected from use by other users. The analytical aspect brings to light the user’s need to choose and think which password is related to which particular system. The sensory aspect brings to light the mental activity of remembering or forgetting. The password functions in each of these aspects, each of which causes a different concern for users.

It is the user’s concern that makes an issue like ‘password’ important, and the aspects show the ways in which the issue can be Down-To-Earth (DTE) in mandatory IS use. The above analysis has shown that what is usually assumed to be a single issue password, is transformed into at least three DTE issues, each related to the meaning and normativity of its aspect. The analysis also shows that from the DTE point of view password is no longer a single issue. In such ways many of the issues in Table 2 were found to have multiple aspects that made them meaningful to users, each relating to something the users said. Once we understood the issues in depth, aspectual analysis helped to reveal hidden issues that are of concern to users.

6. Discussion and conclusions

6.1 Summary

This paper has discussed a new way of investigating mandatory information system use (MISU). It involves how to uncover and understand issues that are important in the everyday working life of system users using Dooyeweerd’s aspects: ‘down-to-earth’ (DTE) issues as introduced by Basden & Ahmad (2011). Sometimes DTE issues relate to formal tasks, sometimes to informal tasks, and sometimes to unofficial ways of using the IS that were not foreseen by system designers or implementers.

Largely unstructured interviews were conducted with system users. Dooyeweerd’s suite of fifteen aspects was used, mainly during analysis, to understand and reveal DTE issues. For each utterance of each interviewee, the main aspects (employed as categories of distinct ways in which things may be meaningful) were identified that make the utterance meaningful to, and in the context of, the interviewee.

Standard interpretive and qualitative analysis techniques can often miss them, but augmenting them with Dooyeweerd’s aspects helps reveal those that are hidden and provide deeper understanding of those that are not. DTE issues are not always easy to discover, partly because they are not anticipated by the theories that usually guide the researcher (theoretical reason), and partly because many are hidden behind what interviewees say (practical reason). Though some interpretive and qualitative analysis techniques, such as Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), can often avoid the first problem by bypassing the theories, they still face the second.

This research contained both types of cases. A number of issues, such as `bored with system features’, are DTE issues discovered by qualitative methods, but by identifying the main aspect that makes them meaningful, our understanding of them can be deepened and widened (for example, beyond boring user interfaces, to boredom in the life of the users). Other issues identified by qualitative methods, such as password, are shown by aspectual analysis to hide a set of different concerns that are meaningful to users. Such hidden issues are revealed by identifying aspects that make what users say meaningful. It is the set of concerns that make the password an issue to users, rather than the password as such. This research thus demonstrates the facility of Dooyeweerd’s aspects to reveal DTE issues, so it will be used in a fuller study of MISU.

6.2 Limitations of this research

This research has demonstrated a method by which DTE issues may be revealed, but it exhibits limitations. One is that all the interviews were carried out in a single organisation. It is possible, therefore, that it was the organisational context that made Dooyeweerd’s aspects useful, and that they would be less useful in other organisations. This is unlikely because there was nothing in the Dooyeweerdian analysis that depended on, or presupposed, a particular organisational context. IS use in other organisations will be analysed in the full study.

Another limitation is that only one qualitative analysis method has been used, that of Tesch (1990) and that this had specific limitations that happened to be overcome by Dooyeweerd’s aspects. As Creswell (2007) states, “Unquestionably, there is no single way to analyze qualitative data. It is an eclectic process in which you try to make sense of the information. Thus the approaches to data analysis by qualitative writers will vary considerably”. It is possible that other methods, such as Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), might reveal DTE issues without needing help from Dooyeweerd’s aspects. Whether this is so, remains to be explored, but initial indications suggest otherwise. Both Grounded Theory coding and Klein & Myers’ (1999) interpretation already assume that certain things are meaningful to the researcher. For example Lamb & Kling (2003) report use of Grounded Theory methods to reconceptualise the user as a social actor, and emerge with four main dimensions: affiliation, environment, interaction, and identity. A closer look, however, reveals that these four concepts were already identified in their discussion of extant theoretical discourse on IS use. Such dimensions are, according to Dooyeweerd, rooted in aspects as spheres of meaning, whether they are recognised or not, and usually omit several important aspects. So it is likely that Dooyeweerd’s aspects can enrich any qualitative analysis technique.

6.3 Strengths and contributions of this research

Whereas most qualitative analysis techniques try to reveal what issues are important, Dooyeweerd’s aspects focus on why they are important, and on their normative content (good / bad). As Habermas (1987) and others have pointed out, it is meaning and normativity that are important in the shared background knowledge of people (their life world), so Dooyeweerd’s aspects are uniquely attuned to the everyday experience of people. That Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects cover, as far as is known, all ways of meaning and modes of being and functioning that are known gives it a flexibility that Cote et al. (1993) believe important to doing qualitative analysis.

Dooyeweerd’s approach inherently recognises the illocutionary meaning that is hidden underneath or behind what people express in their sentences, because he sees the sentences as human functioning in the lingual aspect rather than merely as sequences of symbols. Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects helps us reveal this illocutionary meaning because the illocutionary meaning of sentences is what they mean within the (multi-aspectual) human activity in relation to which the sentences are uttered. Interviewees (IS users in this case) are seen simultaneously as individuals and also as social actors, as Lamb & Kling (2003) recommend.

“A chronic problem of qualitative research,” write Miles and Huberman (1994, p. 56), “is that it is done chiefly with words, not with numbers. Words are fatter than numbers and usually have multiple meanings”. Since, to Dooyeweerd, all things exhibit all aspects, multiple meanings are to be expected rather than seen as a troublesome exception. Dooyeweerd is thus commensurate with Klein & Myers’ (1999) principles of interpretive research; indeed these principles might benefit from Dooyeweerd more generally.

An important issue therein is the relationship between the researcher and the researched. To Dooyeweerd, both function as subjects to the same aspectual laws, the kernel meanings of which may be grasped by our intuition, though they cannot be grasped by theoretical thought. Aspectual meaning transcends cultures, so an intuitive grasp thereof can facilitate analysis across cultures. So Dooyeweerd’s aspects might offer a way towards some mutual understanding not only between the researcher and the researched, but also across different cultures. It may be noted that the authors of this paper come from Malaysia and the United Kingdom.

It might also be because of the intuitiveness of aspectual meanings that this approach seems able to reveal in a one-hour interview the kinds of things that it took (Wenger, 1999) a longitudinal ethnographic study to reveal. This approach might therefore offer efficiency and speed of analysis without sacrificing sensitivity to what is truly meaningful to the interviewees.

6.4 Conclusion

This paper can be interesting to both academician and practitioner. To the academician it, establishes a new approach to understanding, thinking about and discussing IS use: ‘down-to-earth’ issues. To the practitioner, it provides, in draft form, a method of analysing situations of IS use to reveal what is important and meaningful to the users rather than to, researchers, IS developers or senior managers for example, in the situation of use.

It might, however, be extendible in two ways. One is to ask whether Dooyeweerd’s aspects can be used other than with qualitative analysis. In particular, could Dooyeweerd’s aspects be used on their own to identify DTE issues? Winfield’s ‘Multi-aspectual Knowledge Elicitation’ method used Dooyeweerd’s aspects on their own to surface many meaningful concepts (Winfield, 2000; Winfield & Basden, 2006; Winfield, et al., 1996). However, to employ Dooyeweerd’s aspects with existing methods of qualitative analysis has advantages of capitalising on widely-known skills and also of being more understandable.

Another extension is to apply it not to current IS use, but to future or imagined IS use, such as in design. To employ Dooyeweerd’s aspects in design one would ask in what ways each aspect might manifest itself in the designed situation of IS use, perhaps with reference to aspectual studies of DTE issues in existing use. In either case, this research offers a way of finding out what is truly important in IS use, rather than trying to fit IS use into the mould of existing theory.

Appendix 1 – The information systems studied

There are various systems used and it is not an integrated type of system. The systems are known as Local Government Information System (LoGInS), Finance Information System (FINIS) and, Assessment and Valuation IS (AVIS). However, since the case study looks at the system that captures all business process, even though it is not integrated, it is still important and must be used by users who work in organisation. During the interview period, the organisation was in a process of implementing a new system known as e-PBT that will replace LoGInS. E-PBT is created by vendor that has been selected by the Federal Government and had to be used by all local authorities by end of 2010 (the interviews took place a year earlier).

AVIS is designed specifically for tax assessment calculation and valuation of assets until the issuance of bills charged to the related resident since 2008. FINIS is meant for accounting related until reporting the financial performance. LoGInS is a system that captured most of the business processes with other information not stored in AVIS and FINIS. LoGInS is the oldest system used, followed by FINIS and the latest system introduced is AVIS. AVIS is the only system that was designed by organisation’s personnel, who are well versed with the whole process of tax assessment. FINIS and LoGInS were customised based on user’s requirements.

Since the system is not integrated, all information needed was transferred manually, from AVIS to LoGInS then to FINIS. This causes difficulty. During the transmission of data there were cases where some data have been left out and figures were not the same as given by the source system. This matter currently is taken into consideration by management.

About the authors

i. Hawa Ahmad – (h.ahmad@edu.salford.ac.uk / hawahmad@iium.edu.my) School of Business, University of Salford, United Kingdom; Kuliyyah Economics and Management Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia

ii. Andrew Basden – (sbs@basden.demon.co.uk) School of Business, University of Salford, United Kingdom

REFERENCES

Book

Basden, A. (2008). Philosophical Frameworks for Understanding Information Systems. Herschey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

Clouser, R. A. (1991). The Myth of Religious Neutrality: An Essay on the Hidden Role of Religious Belief in Theories (Publication., from University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, London:

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approach (2nd ed.): Sage Publications Ltd.

Dooyeweerd, H. (1955). A New Critique of Theoretical Thought (Vol. I-IV). Jordan Station, Ontario.: Paideia Press (1975 edition).

Fishbein, M., &Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research: Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research: New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Habermas, J. (1987). The Theory of Communicative Action; Volume Two: The Critique of Functionalist Reason: McCarthy T, Polity Press.

Kane, S.C. (2006). Multi-aspectual Interview Technique (MAIT). Doctoral Thesis, University of Salford, Salford, U.K.

Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. United States of America: SAGE Publications.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Source Book (2nd ed.). Newbury Park CA: Sage.

Myers, M. D. (2009). Qualitative Research in Business & Management. Great Britain: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin., I. S. (2004). Qualitative interviewing : The Art of Hearing Data (2nd ed.): London : SAGE.

Schwandt, T. A. (2001). Qualitative inquiry: A dictionary of terms (2nd ed.): Sage.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (Eds.). (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques: Sage Publications, Inc, Newbury Park.

Tesch, R. (1990). Qualitative Research: Analysis types and software tools. Bristol: Falmer Press.

Trauth, E. M. (2001). The Choice of Qualitative Methods in IS Research: Idea Group Publishing

Journal Articles

Adamson, I., & Shine, J. (2003). Extending the New Technology Acceptance Model to Measure the End User Informations Systems Satisfaction in a Mandatory Environment: A Bank’s Treasury. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 15(4), 441-455.

Ahmad, H., &Basden, A. (2008). Non-discretionary use of information system and the technology acceptance model. Paper presented at the 4th IRIS Postgraduate Conference, Salford, United Kingdom.

Alvarez, R., &Urla, J. (2002). Tell me a good story: using narrative analysis to examine information requirements interviews during an ERP implementation. The DATA BASE for Advances in Information Systems, 33(1).

Ang, C.-L., Davies, M. A., & Finlay, P. N. (2001). An Empirical Model of IT Usage in the Malaysian Public Sector. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 10, 159-174.

Avison, D., & Myers, M. (2005). Reseach in Information Systems: A Handbook for Research Supervisors and their Students: McGraw-Hill.

Barki, H. (2008). Thar’s Gold in Them Thar Constructs. The DATA BASE for Advances in Information Systems, 39(3).

Basden, A. (2001). A Philosophical Underpinning for IT Evaluation. Paper presented at the Eighth European Conference on Information Technology Evaluation.

Basden, A. (2002). A Philosophical Underpinning for ISD. Paper presented at the European Conference of Information System, Gdańsk, Poland.

Basden, A., & Ahmad, H. (2011). Down-To-Earth Issues in (Mandatory) IS Use; Part I – Types of Issue. Paper presented at the Proceeding of the 17th IIDE Annual Working Conference, Maarssen, Nerthelands.

Chang, K.-C., Lie, T., & Fan, M.-L. (2010). The impact of organizational intervention on system usage extent. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 110(4), 532-549.

Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Computer Self-Efficacy: Development of a Measure and Initial Test. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), 189-211.

Cote, J., Salmela, J. H., Baria, A., & Russell, S. J. (1993). Organizing and Interpreting Unstructured Qualitative Data. Sport Psychologist, 7(2), 127-137.

Davis, F. D. (1986). The Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States of America.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

Holden, R. J. (2010). Physicians’ beliefs about using EMR and CPOE: In pursuit of a contextualized understanding of health IT use behavior. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 79(2), 71-80.

Jain, A., & Ogden, J. (1999). General practitioners’ experiences of patients’ complaints: qualitative study. BMJ, 318(7198), 1596.

Joneidy, S., & Basden, A. (2011). Exploring Dooyeweerd’s Aspects for Understanding Perceived Usefulness of Information Systems. Paper presented at the Proceeding of the 17th IIDE Annual Working Conference, Maarssen,Netherlands.

Kaplan, B., & Maxwell, J. A. (1994). Qualitative research methods for evaluating computer information systems. In: J. G. Anderson, Aydin, C.E. and Jay, S.J. (Ed.), Evaluating Health Care Information Systems, Methods and Applications: Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Klein, H. K., &Myers, M. D. (1999). A Set of Principles for Conducting and Evaluating Interpretive Field Studies in Information Systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67-94.

Lamb, R., & Kling, R. (2003). Reconceptualizing Users As Social Actors In Information Systems Research. MIS Quarterly, 27(2), 197-235.

Lin, H.-F. (2010). An investigation into the effects of IS quality and top management support on ERP system usage – Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 21(3), 335-349.

Linders, S. (2006). Using the Technology Acceptance Model in determining strategies for implementation of mandatory IS. Paper presented at the 4th Twente Student Conference on IT, Enschede, University of Twente.

Mahmood, M. A., Hall, L., &Swanberg, D. L. (2001). Factors Affecting Information Technology Usage: A Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Literature. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 11(2), 107-130.

Nandhakumar, J., & Jones, M. (1997). Too Close for Comfort? Distance and Engagement in Interpretive Information Systems Research. Information Systems Journal, 7, 109-131.

Özer, G., &Yilmaz, E. (2011). Comparison of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior: An application on accountants’ information technology usage. African Journal of Business Management 5(1), 50-58.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2 ed.): Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 137-145.

Ramachandran, V. S. (2011). Face to Face. Resonance, 88-99.

Robson, S., & Foster, A. (1989). Qualitative Research in Action: Edward Arnold.

Rouibah, K., Hamdy, H. I., & Al-Enezi, M. Z. (2009). Effect of management support, training, and user involvement on system usage and satisfaction in Kuwait. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 109(3), 338-356.

Searle, J. R. (1968). Austin on Locutionary and Illocutionary Acts. The Philosophical Review, 77(4), 405-424.

Shih, Y. Y., & Huang, S. S. (2009). The Actual Usage of ERP systems: An Extended Technology Acceptance Perspective. Journal of Research and Practice in Information Technology, 41(3), 263-276.

Singletary, L. L. A., Akbulut, A. Y., & Houston, A. L. (2002). Innovative Software Use After Mandatory Adoption. Paper presented at the Proceeding of 8th Americas Conference on Information Systems.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

Watson, G. (Ed.). (1987). Writing a Thesis: A Guide to Long Essays and Dissertations (First ed.). London and New York: Longman.

Wenger., E. (Ed.). (1999). Communities of practice : learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge Cambridge University Press.

Winfield, M. (2000). Multi-Aspectual Knowledge Elicitation. Unpublished PhD, University of Salford, Salford.

Winfield, M. J., & Andrew, B. (2006). Elicitation of Highly Interdisciplinary Knowledge: Springler Science+Business Media Inc.

Winfield, M. J., Basden, A., &Cresswell, I. (1996). Knowledge elicitation using a multi-modal approach. World Futures, 47, 93 – 101.

Wojnar, D. M., & Swanson, K. M. (2007). Phenomenology: An Exploration. J Holist Nurs, 25(3), 172-180.

Yoon, Y., &Guimaraes, T. (1995). Assessing Expert Systems Impact on Users’ Jobs. Journal of Management Information Systems, 12(1), 225-249.

Yousafzai, S. Y., Foxall, G. R., &Pallister, J. G. (2007). Technology Acceptance: A Meta-analysis of the TAM: Part 1. Journal of Modelling in Management, 2( 3), pp. 281-304.

Website

Dictionary.com. Assessed 8th February 2011. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/aspects?r=66

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply