ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Definitions In Legal Discussions

No comments yet 1. Introduction

1. Introduction

It is well-known that in many a legal dispute the question arises what the exact extension of a predicate is. The difference of opinion in such cases almost always concerns the question as to whether an incident comes under the reach of a concept that is expressed by a particular word or phrase in a legal text in which the rights and obligations of the persons holding legal rights are established (for example a law or agreement). In such cases of difference of opinion the lawyers are forced to declare what a certain word or group of words means in their opinion. And in the discussions that may be carried out they often also give definitions of the words or phrases concerned and will, in principle, have to justify the acceptability of such definitions.

The question now is: how do lawyers – and more particularly judges – deal with this kind of language controversy; what kind of definitions do they give and how do they present and justify them? I attempt in this article to give an interim answer – an interim answer due among other things to the insufficiency of the systematic research I have done into the judgements of judges in The Netherlands.

The article is set up as follows. In paragraph 2 a case is given in rough outline and in paragraph 3 there is the development of part of the legal discussion as a result of that case. In paragraph 4 I go into the question of which types of definition can be distinguished and how the plausibility of each of these different types of definition can be argued. In paragraph 5 I reconstruct part of the legal discussion in the light of the typology of definitions dealt with in paragraph 5. Paragraph 6 constitutes the conclusion of this article.

2. A case: fire in a building[i]

Mr. Matthes owned a house of nine rooms. In 1979 the house was inhabited by Matthes with his wife and four children and also by a tenant and her son. All the rooms were in use by Matthes and the members of his family, except for one room on the first floor which was used by the tenant.

Matthes wanted to take out fire insurance with the Noordhollandse insurance company and submitted an application form for this purpose for an ‘index/extended insurance for private house’. On the reverse of the form it stated:

1. the applicant declares: a. that the private house on which or in which insurance is requested, is of brick/concrete with a hard roofing, with no business or storage and without increased danger to adjoining properties’.

From 17 July 1979 the Noordhollandse insurance company insured the house for the period until 17 July 1989 including fire risk. The policy for extended building insurance dated 2 August 1979 referred to the house with the addition:

2. ‘serving solely as private house’.

On Monday 3 December 1984 at about eight-thirty p.m. fire broke out in the house resulting in considerable damage. At that time the house was inhabited by Matthes and his wife and a total of five rooms were rented out to three different single gentlemen. Naturally Matthes claimed on the insurance company for the damage which amounted to some 500,000 Dutch guilders. However the company refused payment on the grounds of the insurance since in its opinion the premises insured no longer served as a private house but was used as a room rental business for which during the insured period the use of the insured object was altered, whereas Matthes had not informed the insurance company of the fact. The Noordhollandse appealed to article 293 of the Commercial Code of The Netherlands:

3. ‘If an insured building is given a different use and is thereby exposed to increased danger, so that the insurer, if such had been in existence before the insurance was given, would not have insured the same at all or not on the same conditions, this obligation is terminated.’

Naturally Mattes did not agree with this and went to court. However the lawcourt, the court of justice and the Supreme Court successively declared him to be in the wrong.

3. The course of the legal discussion in this case

The legal discussion for the various authorities concerns to a large degree the question of what meaning should be given to the word ‘private house’ on the application form for the fire insurance and the phrase ‘acting solely as private house’ in the insurance policy. The lawcourt was of the opinion that the word ‘private house’ should have the following meaning:

4. ‘a house that serves as a general rule for the permanent accommodation of several persons who are partially dependent of each other economically and furthermore have an emotional bond with each other.’

This means according to the lawcourt in general:

5. ‘that such persons have a greater concern for each other and each others interests than random otherwise respectable citizens may be expected to have and that the social control of their doings is greater than that normally found among the same citizens.’ The situation on 3 December 1984 was, according to the lawcourt, other than that in 1979, since:

6. ‘the private house was occupied on 3 December 1984 for the greater part by tenants who would require more privacy and whose behaviour was subject to less social control.’

According to the lawcourt this meant that a change of use in the meaning of art. 293 of the commercial code of The Netherlands took place whereby the house was subject to ‘increased fire risk’. Matthes was thus put in the wrong and appealed.

He declared among other things to the court of justice that:

7. ‘a building destined as ‘private house’ should retain this designation irrespective of whether it is occupied by the insured and his family or by the insured with a number of tenants.’

In short Matthes employed another definition of ‘private house’, namely:

8. ‘a building destined mainly for residential purposes.’

In view of this definition of ‘private house’ there is no question of a difference in destination in the light of the policy, since at the time of the fire Matthes lived in the house with his wife and three house-mates/tenants who did not form part of the family. Matthes contended further that:

9. ‘the manner in which the term ‘private house’ was interpreted by me was perfectly in keeping with the normal use of language, in view of the fact that the description ‘private house’ is the most obvious and was employed for the insured object as it was used during the fire.’

The court of justice refuted the plea of Matthes, supporting the rejection by yet another definition of ‘private house’. It stated:

10. ‘the term “private house” on the application form and the words “serving solely as private house” in the relevant policy are to be understood as “private house serving mainly as private dwelling for the insured whether or not with his family”.’

The court of justice then considered that:

11. ‘now that the insured building was inhabited by the Matthes family on taking out the insurance, consisting of husband, wife and four children, together with a tenant with one child, and that when the fire broke out it was occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Matthes with three tenants, there was a question of an actual alteration of usage.

This was all the more convincing now that according to Matthes’ own declaration the rooms concerned were rented out so that the revenue could contribute to the university expenses of his children, the which implied that rental of the accommodation could not be said to lack a certain business nature.’ And further:

12. ‘that private house as understood by the court should not be taken to mean a building of which, as in the present case, more that half the rooms are let to third parties, and that such building rather had the nature of an accommodation business for the insurance of which a different premium or conditions applied than to the insurance of a dwelling, the which was not contested by Matthes.’ And:

13. ‘the court of justice regarded as obvious the fact that a building of which the owner-occupier had at his disposal three rooms and a guest-room and of which the other five rooms had been let to third parties which in principle were independent of each other and had no reason to occupy themselves with the affairs of their fellow residents, even if they referred to themselves as a community, was exposed to a greater danger of fire than when this building was occupied by a family with children and a single tenant.’

At the court of justice Matthes thus was again said to be in the wrong and determined to appeal to the supreme court.

As plaintiff in appeal he declared essentially the same as before the court of justice, namely that based on the most usual definition of the term ‘private house’ there was no question of a change of use. In his summing up Solicitor General Asser also explored the definition of private house as given by the court and stated the following:

14. ‘The meaning given by the court to the concept “private house” seems to me, where there is talk of “private occupation by

the insured whether or not together with his family” hardly obvious in the first instance in the light of the proposition of the parties. I have not come across this very narrow interpretation of the concept “private house” anywhere, more particularly not in the propositions of the Noordhollandse. On the contrary, the Noordhollandse has stated in the memorandum of reply in appeal that in general speech a private house is considered to be a house occupied by a family, it being of no consequence whether the house is owner-occupied or rented by the occupiers. There should thus not be in the policy any clause stating a home “solely serving for own occupation”, according to the Noordhollandse. The Noordhollandse did state that the situation was different when there was a question of more independent tenants and more particularly an accommodation business, of which according to the Noordhollandse there was a question in this case. In this connection I would also wish to assume that what the court considered should be read thus that “private house” is taken to mean occupied mainly by a person alone or as a family, whereby the intention is other than occupation by tenants. The explanation of the court thus amounted to what the lawcourt considered in somewhat elaborate terms.’

Finally the Solicitor General advised the rejection of the appeal made by Matthes. The Supreme Court took this advice, considering more particularly the following:

15 ‘Against this background judicial consideration 4.4 is apparently to be so understood that Matthes, in the opinion of the court, could reasonably have understood from the term “private house”, or the words “serving solely as private house” – and that the Noordhollandse could reasonably expect that it should be clear to Matthes – that the use thus described included the situation of the insured who occupied the largest part of the building himself (whether or not together with his family), “a single tenant” was present in the building, but not the situation in which as in the present case, the larger part of the building, namely more than half the rooms, was let to third parties, in which case the building, as the court stated “had rather the nature of an accommodation business”.’

Law professor Van der Grinten in his note following the judgement criticises this pronouncement:

16. ‘Has the court rightly assumed that the words “serving solely as private house” are to be interpreted as “dwelling serving for the private accommodation of the insured”? (…) I would be inclined to judge this differently than the court. The words “as private house” could be interpreted as “accommodation”. The circumstance that an important part of the house was later – after taking out insurance – used by the tenants as residence does not involve any alteration in the use.’

At first sight this discussion is rather unsatisfactory. More particularly it is not clear on what the lawcourt and the court of justice each based their own definition of the term ‘private house’ and neither do either of the bodies go into the argument of Matthes that his definition of ‘private house’ fits in most closely with normal speech. Due to this fact the discussion has all the characteristics of a yes-no discussion but nevertheless one with considerable financial consequences. This naturally gives rise to the theoretical legal question of how free the judge is in giving meaning to non-legal terms in the explanation of written agreements and to what extent he can be required to motivate his definitions.

In short, this discussion – and more particularly the judgement of the court of justice – demands rational reconstruction. But this is only possible when we evolve a theory about definitions.

4. A pragmatic-dialectic approach to defining

The theory about definition and the theory about argumentation are closely related, as Viskil showed so convincingly (see Viskil 1994a, 1994b, and 1995). Definition is regarded as an important instrument in interpretation, assessment and formulation of points of view and arguments. According to the classic view, a definition is a statement concerning the essence of a thing. In modern theories with a perspective of dialogue on argumentation, a definition is considered in the first instance to be an instrument to clarify discussions. It is necessary for partners in discussion to clarify their terms, since not only the soundness of arguments but also the acceptability of, for example, standpoints are only to be realised if the meaning of the terms is clear.

Viskil proposes considering definition as a speech act and in view of that fact he arrives at the typology of defining speech acts and thus corresponding definitions, to which the following three also belong:

17.

a. Stipulative definition

b. Lexical definition

c. Stipulative lexical definition.

The act of stipulative definining is a section of the class of language usage declaratives, a subclass of declaratives. Stipulative defining is bound to felicity conditions (18) and (19) (see Viskil 1994a: 144 et seq.).

18. Essential condition for stipulative defining

Performing speech act T counts as establishing the meaning of a word (or phrase) in order to clarify this meaning for the listner or reader.

19. Propositional content condition of stipulative defining

Each proposition which is expressed in a sentence of which the subject term is formed by a quoted (group of) word(s) and the predicate exists (1) of a verb that indicates that the remaining portion of the predicate is the meaning of the subject term and (2) one or more words or groups of words with or without modifier.

Examples which meet the propositional content condition are the following.

20.

a. The word bungalow means ‘a house where all the rooms are on the same level’ (= connotative stipulative defining).

b. Inventiveness means ‘resourcefulness’ (= stipulative defining by means of the giving of a synonym).

c. I take breaker’s yard to mean: junkyard, centre for used car parts, wrecker’s yard and car damage businesses (denotative stipulative defining).

The act of lexical defining is a section of the class of language usage assertives, a subclass of assertives. This speech act is bound to the essential felicity condition (21) (see Viskil 1994a, 153 et seq.)

21. Essential condition of lexical defining

Performing speech act T counts as a description of the meaning in which language users use a word (or phrase) in order to clarify this meaning to the listner or reader.

The propositional content condition of lexical defining is identical to that of stipulative defining. The speech acts are thus identical with respect to content, but they differ in the illoctutionary purpose, which is also noticeable in the essential condition (but also of course in the preparatory condition and the sincerity condition). For that reason the examples given in (20) could also be examples of lexical definitions.

Some definitions are not purely stipulative or purely lexical, but partly stipulative and partly lexical. In the simplest mixture of these two speech acts the speaker or writer attempts to clarify a word by a description of the meaning of such word which is valid as an establishment of the meaning. This speech act can be indicated by the term ‘stipulative-lexical defining’. There are at least two sub-types. First there is the case where the speaker or writer defines a term in the conventional way while declaring at the same time that in using that term he will also keep to that meaning, see example (22).

22. The word chair usually means a seating unit for one person and I shall be using it further in that sense.

In the second place there is the case in which the speaker or writer gives a specification of the lexical definition and declares that he will use the term in the meaning of the specification given, see example (23).

23. The word chair usually means a seating unit for one person, but I use this term in the sense of a seating unit for one person and provided with four legs.

In both cases the speaker or writer commits himself to a conventional meaning (the lexical aspect of the definition) but at the same time calls up a situation within which the defined term is used in conformity with the meaning, whether or not specified (the stipulative aspect). The class to which the speech act of ‘stipulative lexical defining’ is to be reckoned is that of the language usage declaratives. But otherwise than in the case of stipulative defining, stipulative-lexical defining is no ordinary language usage declarative, but a combination of a language usage declarative and an assertive. The conditions of success of the speech act ‘stipulative-lexical defining’” then combines the felicity conditions of stipulative defining with that of lexical defining (see Viskil 1994a: 156 et seq.)

24. Essential condition of stipulative-lexical defining

Performing speech act T counts as a description of the meaning in which language users use a word (or phrase) which has the force of establishing this meaning for the language usage of the speaker or writer, in order to clarify the meaning for the listner or reader.

Naturally the propositional content condition for stipulative-lexical defining is also equal to those of stipulative definition.[ii] That is to say that the sentences under (20) may also count as examples of stipulative-lexical defining.

Viskil also pays attention in his approach to the question of how definitions can be justified, for which purpose he makes use of the pragmatic-dialectic argumentation theory.[iii] The justification of a definition is based on the fact that the definition should solve the problems for which it is drawn up and is acceptable to the definer as well as to the persons for whom it is intended. The definer justifies his definition to convince the listener or reader of the acceptability of his definition and thus obtains inter-subjective agreement regarding the definition.

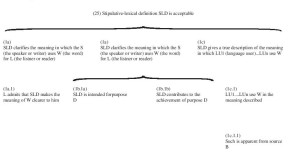

A stipulative definition should be an adequate attempt at clarification and be functional. A lexical definition should be an adequate attempt at clarification and contain a true proposition: the meaning that is described in a lexical definition should concur with the meaning in which the language users in question use the defined word. In order to be acceptable a stipulative-lexical definition should answer to three demands: the definition has to be an acceptable attempt at clarification, be functional and give a description of the meaning that agrees with the facts. The standard argumentation structure for the defence of the acceptability of a stipulative-lexical definition, when seen as described, appears to be as follows (see Viskil 1994a: 253).

5. A rational reconstruction of part of the legal discussion of the case

A rational reconstruction of an argumentative discussion or a part thereof is a reformulation of that discussion or of such part of it with a view to the testing of its rationality. Such a reconstruction always assumes of course a theoretical perspective from where is reconstructed. Let us now look at our legal discussion through the spectacles of the theory sketched above regarding definition. We are now able to pose the following two questions: (a) of what type are the definitions which play a part in this discussion and (b) are the definitions given – dependent on their type – adequately justified?

Question (a) is of course not solely to be answered by regarding the form of the sentences in which the definitions are formulated. After all, we have seen that the three types of defining speech acts should be distinguished based on their illocutionary force, expressed also in the different essential conditions. If we base ourselves on the illocutionary purport we have to refer for the reply to question (a) to the difference between the legal bodies and the other participants of this discussion. The following legal rule is here important:

26. Should there be a difference of opinion between the parties concerning the explanation of a term in a written agreement, the judge of the facts of the case is at liberty to explain the term concerned independently, quite apart from what the parties advance in this connection.[iv]

In other words: in the matter of the case dealt with here the lawcourt and the court of justice were at liberty to give an independent meaning to the term ‘private house’, without having to take into account what Matthes and the Noordhollandse had advanced in that case. This explains, in my opinion, why neither the lawcourt nor the court of justice went into the argument advanced by Matthes that his definition of the term ‘private house’ linked up more closely with the normal use of language.

Rule (26) indicates further that defining speech acts which are advanced by judges in the context of the explanation of agreements, should be regarded in any case as being of a stipulative nature. After all, the definition by the judges of the term ‘private house’ cannot be regarded as other than an establishment of the meaning which is aimed at making matters clear(er) to the listener or reader. The question is however whether there can be any question of a purely stipulative definition. This amounts to the question of whether the judge is also at liberty to explain terms in an agreement – and certainly non-legal terms – entirely free of normal use. In my opinion the judge does not enjoy such liberty. After all, if we assume that for the explanation of agreements it is a directive what the parties should have understood by it and what they were to expect of each other, this cannot be taken apart from the conventional meaning of terms which are used in a linguistic community. This leads to the fact that definitions that are given by judges in similar circumstances, bear the nature of stipulative-lexical definitions.

If we assume that the judge of the facts advances stipulative-lexical definitions in this context, we can also ask ourselves the nature of the sub-type of the given definition of ‘private house’. It seems to me that we are here confronted with a specifying stipulative-lexical definition in the sense that the judge gives a specification of the daily term ‘private house’, as found, for instance, in Van Dale (the Dutch authoritative dictionary).

27. Van Dale – Groot woordenboek der Nederlandse taal, (‘Van Dale – Large dictionary of the Dutch language’), 11th edition

private house (n), house, arranged as dwelling or where a person lives, as against office, shop (…);

The parties in the trial took a different position in this discussion. They will more particularly have to make clear to the judge what they were to expect of each other in the context of the agreement. It is therefore clear that they would make a claim in particular on the conventional meaning and thus advance definitions that were especially lexical. After all, as far as they are concerned it means especially giving a description of the meaning which language users within a certain language community give to a particular word or group of words. In our discussion this applies both to Matthes (see the verdicts (7), (8) and (9) above) as for the Noordhollandse, as far as this can be concluded from what Solicitor-General Asser said about it (see (14) above).

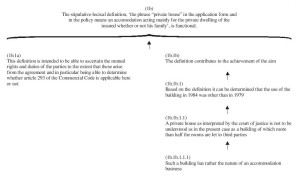

Once we have ascertained with what kind of definitions we are confronted in the discussion, we can also check whether the definitions are justified adequately (question (b)). If we assume, for example, that the court of justice gave a stipulative lexical definition of the term ‘private house’, then for the reconstruction of the account of this definition structure (25) should be taken as basis. It is now striking that in the plea of the court of justice no attention at all was paid to two of the three coordinative primary arguments in this standard structure: no single word is addressed either to (1a) nor to (1c). Attention is paid on the other hand to the question of whether the definition is functional. This part of the plea may be (partially)

reconstructed as follows.

In the scheme of this article it naturally does not concern the question of whether the definition given by the court of justice was adequate and whether the argumentation advanced was sound. The above is to illustrate more than anything that for a critical judgement of this type of discussion and argument a rational reconstruction is necessary in terms of a theory regarding definitions.

6. Conclusion

I assume for the time being that the discussion which I have given here is representative of those cases in which judges have to make a judgement on the meaning of non-legal words and groups of words when explaining written agreements.

It may be concluded that in this context judges give other types of definitions than the parties. Judges advance stipulative-lexical definitions whereas the parties make use of lexical definitions. In addition is can be stated that judges on the justification of the plausibility of the definitions they give do not pay any attention to arguments which are concerned with the question of whether the given definition of a word or group of words makes the meaning clear or clearer, neither do they answer the question whether the description of the meaning agrees with the facts, but merely go into the question of whether the definitions they provide are functional. Further research should indicate to what extent this picture is right and, if it is, to what extent this development has its origins in the specific nature of this kind of legal discussion.[v]

NOTES

i. See Supreme Court of The Netherlands 10 August 1988, NJ 1989, 238.

ii. See Van Haaften (1996) for treatment of the question of which types of definition generally arise in the context of legislation and judicial pronouncements.

iii. See F.H. van Eemeren & R. Grootendorst (1992) regarding the basic assumptions and approach of the pragmatic-dialectic argumentation theory.

iv. See also the final pleading of the Public Prosecutor for the Supreme Court of The Netherlands dated 6 February 1987, NJ 1987, 438, under 3.2 with further references.

v. It is perhaps good to notice that what I have said about definitions is by no means in contradiction with the now rather generally accepted idea of – as H.L.A. Hart calls it – ‘open texture’ of legal concepts and concepts in general, which means that it is in principle impossible to frame rules of language which are ready for all imaginable possibilities. That is to say that however complex our definitions may be, we cannot render them so precise as for them to be delimited in alle possible directions. It is thus not possible for any given case to say definitely that the concept either does or does not apply to it. As Hart (1983:275) puts it: ‘We can only redefine and refine our concepts to meet the new situations when they arise’. But of course all this does not mean – as sometimes people seem to conclude – that definitions are of no use at all.

REFERENCES

Eemeren, F.H. van & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication and Fallacies. A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale: LEA Publishers.

Haaften, T. van (1996). Typen definities in de taal van het recht. Taalbeheersing 18, 255-269.

Hart, H.L.A. (1983). Jhering’s Heaven of Concepts and Modern Analytical Jurisprudence. In: H.L.A. Hart, Essays in Jurisprudence and Philosophy (pp. 265-277). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Viskil, E. (1994a). Definiëren. Een bijdrage tot de theorievorming over het opstellen van definities. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

Viskil, E. (1994b). Definitions in argumentative texts. In: F.H. van Eemeren & R. Grootendorst (eds.), Studies in Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 79-86). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Viskil, E. (1995). Defending definitions, A pragma-dialectical approach. In: F.H. van Eemeren et al. (eds.), Perspectives and Approaches, volume 1 (pp. 428-438). Amsterdam: ISCA.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply