ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Does The Hedgehog Climb Trees?: The Neurological Basis For ‘Theoretical’ And ‘Empirical’ Reasoning Patterns

No comments yet 1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Human beings use two contrasting patterns of reasoning, often called the “empirical” (“pre-logical”, “traditional”) mode and the “theoretical” (“logical”, “formal”) mode. The contrast between these two modes is most marked in discourse when the demands of logical patterns contradict common-sense attitudes and the ability to establish the reliability of premises. Thus, the following syllogism (Scribner 1976: 485):

1. All people who own houses pay house tax. Boima does not pay a house tax. Does he own a house? can have in actual discourse two different answers. One exemplifies the theoretical mode of reasoning, and is assumed to be the correct one:

1.1 a. No, he does not.

The second answer is:

1.1 b. Yes, he has a house.

with further elaboration (if asked): “But he does not pay the tax, because he has no money.” This mode is called the empirical mode. In discourse, referring to the situation described in the cited syllogism, it is the “incorrect” traditional pattern of reasoning, and not the logical one, that is correct. Similarly, syllogisms with false premises like (2):

2. All monkeys climb trees. The hedgehog is a monkey. Does the hedgehog climb trees, or not?

also can be given two different answers: one theoretical, but false (which deductively follows from the premises):

2.1 a. Yes, he does.

the other an empirical, inductively oriented one, with the claim that either the second premise is false:

2.1 b. The hedgehog is not a monkey, or that one does not know what it is all about or whether it is true at all:

2.1 c. I have not seen hedgehogs, I do not know whether they climb trees or not .

According to cross-cultural and educational studies people in pre-literate cultures invariably respond empirically to such questions; in fact, they seem unable to comprehend a request to say what follows from a set of premises when they do not have first-hand knowledge that they are true. Pre-school and very early school-age children in all cultures likewise respond empirically, according to educational and developmental studies. These findings have prompted a number of questions. What causes the transition from the pre-logical to the logical mode? Is it an ontogenetic development, or is it culturally conditioned? If the latter, is the determining factor literacy alone, or a specific kind of schooling? When children (or pre-literate adults) acquire the logical mode, do they still use the pre-logical mode? How is the ability to use these modes grounded in the brain? In particular, what contribution does each hemisphere of the brain make to each mode? In what follows I aim to synthesize the results of twentieth century research into these patterns of reasoning. In particular, I will describe some unique but little known neurological research which shows that, contrary to Piaget’s and others’ claims, the empirical, pre-logical mode remains a part of the discursive repertoire of adults in literate European-type civilizations. It is located in the right hemisphere of right-handed people, whereas the logical mode is located in the left hemisphere.

2. Developmental research

Piaget (Piaget 1954, 1971; Piaget and Inhelder 1951) proposed a hypothesis of stages of cognitive development, and asked at which stage formal operations appear. Piaget claimed that they appear at a later, fourth stage (between 12 and 15 years[i], when interpropositional and intrapropositional connections are acquired, and that they involve abilities of two types – to deal with the inner structure of a proposition and to understand causal, inferential and other connections between propositions. Later, Piaget and his followers rejected Chomsky’s “predetermination” position of the inborn nature of cognitive stages, including reasoning abilities (Green 1971, Piattelli-Palmarini 1979). Some participants in the polemics between Chomskian “innatism” and Piagetian “constructivism” – Cellérier, Fodor, Toulmin, et al. -maintained, however, that the two approaches are compatible.

3. Cross-cultural research

Cross-cultural studies started with Lévy-Bruhl’s (1923) claim that the mode of thinking in a “primitive” society follows its own laws and differs from that of an “advanced” society[ii]. He called this mode “prelogical”, as opposed to the advanced “logical” mode. As was pointed out later by Luria (1976: 7), Lévy-Bruhl was the first to state that there were qualitative differences in the primitive way of thinking and to treat logical processes as the product of sociohistorical development.[iii]

The first experiments in checking differences in patterns of reasoning with usage of syllogisms were undertaken by a Soviet psychologist, Alexander Luria, as part of a wider investigation of cognitive development in the context of cultural and social changes[iv]. The research was undertaken in the early thirties in remote areas of Uzbekistan and Kirghizia at the period when traditional, preliterate populations “met” with the new contemporary social and economic conditions. The results were presented in Luria’s monograph, Cognitive Development: Its cultural and Social Foundations (1977).[v] They defined the form (work with syllogisms) of further research in this area in different parts of the world (Cole, Gay, Glick & Sharp 1971; Cole & Scribner 1974; Scribner 1976; Sharp, Cole & Lave 1979; etc.).

3.1 Luria’s experiments

Luria’s experiments involved two groups of people. One included illiterate men and women from remote villages who were not involved in any modern social activities -“non-schooled” individuals. The other group included men and women with some literacy training (from very basic to more advanced) who were participating in modern activities (running the collective farms in different capacities, education of children in kindergartens and in primary schools) – “schooled” individuals. The subjects were presented with two types of syllogisms – one type with content related to the subjects’ own practical experience, the other with content not related to such experiences. The syllogisms consisted of major and minor premises and of a question, to which the subjects were asked to provide an answer. Testing aimed at the following abilities:

1. Ability to repeat the whole syllogism[vi]. The goal was to see whether the subjects perceived a syllogism as a whole logical schema, or only as isolated statements.

2. Ability to make deductions in two types of syllogisms:

a. those with familiar content in the premises and

b. those with unfamiliar content. The goal was to see what type of mode they follow. In both cases subjects were asked to explain how they arrived at their answer, in order to see where they used their practical experience and where the answer was obtained by logical deduction. The results were as follows:

1. Repetition of syllogisms: Schooled subjects saw the overall structure of the syllogism, and repeated it easily. Non-schooled subjects saw the syllogism not as one unit, but as a number of unconnected statements. Here are some examples (Luria 1976: 102-117):

3. Precious metals do not rust. Gold is a precious metal. Does it rust or not?

The repetitions of the non-schooled subjects were like the following:

3.1

a. Do precious metals rust or not? Does gold rust or not?

b. Precious metals rust. Do precious metals rust or not?

c. Precious metals rust. Precious gold rusts. Does precious gold rust or not? Do precious metals rust or not?

4. The white bears exist only where it is very cold and there is snow. Silk cocoons exist only where it is very hot. Are there places where there are both white bears and cocoons? Repetitions:

4.1

a. There is a country where there are white bears and white snow. Can there be such a thing? Can white silk grow there?

b. Where there is white snow, there are bears, where it is hot, are there cocoons or not?

2. Deduction

a. Syllogisms with familiar content related to everyday experiences, but transferred to new conditions, as in:

5. Cotton grows where it is hot and dry. England is cold and damp. Can cotton grow there or not?

Responses: Non-schooled subjects refused to make any deductions even from this type of syllogism. The major reason for refusals was reference to lack of personal experience (5.1. a, b); only when they were asked to take the words for truth did they sometimes agree to answer (5.1.c). Often if they agreed to answer, the answer ignored the premises, and reasoning was carried out within another framework of conditions (5.1.d):

5.1

a. I have only been in the Kashgar country. I do not know beyond that.

b. I do not know, I’ve heard of England, but I do not know if cotton grows there.

c. From your words I would have to say that cotton shouldn’t grow there…

d. If the land is good, the cotton will grow there, but if it is damp and poor it won’t grow. If it’s like Kashgar country, it will grow there too. If the soil is loose, it can grow there too, of course.

b. Syllogisms with unfamiliar content, where inferences can be made only in the theoretical mode:

6. In the Far North where there is snow, all bears are white. Novaya Zemlya is in the Far North. What colour are the bears there?

Responses: Non-schooled subjects more strongly refused to deal with such syllogisms, often on ethical grounds (6.1.a), or in case they agreed (under special request) to speak, premises were either missing or ignored (6.1.b, c, d), since the subjects made use only of personal experience:

6.1

a. We always speak only of what we see; we don’t talk about what we haven’t seen.

b. There are different sorts of bears.

c. There are different kinds of bears, if one was born red, he will stay red.

d. I do not know, I’ve seen a black bear, I have never seen any other. Each locality has its own animals. If it is white, it will be white, if it’s yellow, it will stay yellow.

In contrast, schooled participants were able in both tasks to solve all the problems: recognize a syllogism, accept the premises, and reason on their basis.

Luria’s conclusions were as follows. Non-schooled subjects reason and make deductions perfectly well when the information is part of their practical experience; they make excellent judgements, draw the implied conclusions, and reveal “worldly intelligence”. But their responses are different when they work with unfamiliar content and must shift to the theoretical mode: they do not recognize a syllogism as a unit (its disintegration into separate propositions without logical connection) and mistrust the premise with content outside their personal experience.

Luria interpreted these differences in reasoning performance within Vygotsky’s theoretical position that “higher cognitive activities remain sociohistorical in nature and… change in the course of historical developments” (Luria 1976, 8), and that sociohistorical development is similar to the development of a child’s cognitive abilities.

3.2. Post-Luria research

Luria’s observations were confirmed in diverse cross-cultural[vii] and education-related researches on the cognitive development of students of different ages/level of education (Scribner 1977; Sharp, Cole & Lave 1979; Scribner & Cole 1981; Tversky & Kahneman 1977; etc.). All studies confirmed that there is a profound difference in the way syllogisms are solved by different groups of people: by educated /literate vs. non-educated /illiterate in cross-cultural tests, and by students of different levels in American schools and universities.

The phenomena described by Luria have been interpreted[viii] by scholars of different specialties (see discussion in Kess 1992, Foley 1997, and Ennis 1998). Some tried to give an account of the phenomena from the point of view of the input of literacy, education and the social environment in development of reasoning processes. Others directly or indirectly connected this issue with developmental problems or with psychological studies of inference in general.

4. Literacy, social changes and education

Cross-cultural and educational studies demonstrated that there is a correlation between literacy, social environment and education on the one hand, and the students’ ability to treat logical problems in a theoretical or empirical mode on the other. It was stated that after a certain level of education individuals are ready to accept a syllogism as a self-contained unit of information which can be dealt with in its own right “as a logical puzzle” (Sharp, Cole & Lave 1979: 75), whereas less-educated individuals “assimilate” the content of the premises to previous experience. The controversy was whether it is education (formal schooling, of which literacy is an obligatory component), or just literacy on its own which is responsible for the cognitive development involving syllogism solving.

Olson (Olson, Torrance, Hidyard 1982; Olson 1994) claims that literacy is sufficient for the formation of syllogism-solving abilities, since literates think in a different way than illiterates, because literacy transforms the nature of thinking: thinking about the world vs. thinking about the representation of the world (Foley 1997: 422). The “literacy” position, though, is not supported by empirical work in education. Scribner and Cole (1981) established in studies among Vai, who have an indigenous vernacular script and are literate in it, that literacy without modernized Western-type schooling does not lead to usage of formal syllogistic reasoning. They see the source of reasoning in literacy in English in the Vai society, which is inseparable from western-type schooling, which includes some specific social practices. Evidently all western-type literacies, which go back to the Greek tradition of reasoning, have this effect on cognitive development.

4.1. “Discourse” theory

Observations in cross-cultural and educational studies gave rise to a “discourse theory” to account for the differences between usage of formal syllogistic reasoning and usage of empirical reasoning. According to this theory, semantic decoding of any text is based on knowledge of the genre (which are actualized in “scripts” or “scenarios” – terms introduced in studies in artificial intelligence – Schank and Abelson 1977, Minsky 1986). Recognition of the genre, and of the script, provides all the implied semantic connections and implicit inferences in the text. Empirical reasoning, used by non-educated people who lack Western-style literacy, relies on traditional oral genres, such as folktales, riddles, myths, legends, narratives, etc. (Scribner 1977, Olson et al. 1982), a list which does not include such a genre as syllogism. So non-schooled people cannot make use of the genre which they do not possess. If they are asked to use it (as in Luria’s and other cases), they simply do not see any sense in doing this, since the syllogism is not a way of reasoning in everyday life. In contrast, for schooled individuals the syllogistic form is a special genre/script with its own laws, a kind of a “game” with familiar rules, a fixed, boxed-in, isolated entity (Ong 1982). The semantic resolution of this script is fully dependent on its inner content and the rules for relating the premises. One is not supposed to check the accuracy of the content in the outside real world. When an individual learns how to use this genre, there is no difficulty in using it, especially in the setting of an experiment where its usage is expected. The syllogistic pattern of reasoning is a part of Western-type schooling, and it is easily acquired in its simple form.

The discourse theory explanation looks highly plausible. If it is correct, it gives rise to another problem: Do schooled subjects completely switch from the empirical way of reasoning to the formal one, or are they using both strategies. Many authors in

cross-cultural research mention in passing that usually individuals use both strategies. This issue will be discussed in more detail in connection with neurological experiments.

4.2. Reconsideration of a developmental interpretation

The data of cross-cultural and educational age-dependent research on operational thinking calls for reinterpretation of Piagetian developmental position. Piaget stated that a) there are four obligatory stages of cognitive development, b) they appear and succeed one another at a certain age, and c) there are qualitative differences in mental processes between the stages.

Cross-cultural studies do not support the idea that the fourth stage, when formal thinking develops, is ontogenetically obligatory, because in pre-literate cultures individuals do not automatically develop it. Piaget is right that this ability appears at a certain age. But it is evident, that it appears not in the course of ontogenesis, but only in the course of certain cultural needs in the society which puts forward certain cognitive tasks. Thus, differences in operational thinking do not constitute part of the “normal” course of development, but are the outcome of schooling and differences in social environment (Brown 1977, Tulviste 1979, Ong 1982), which provide a special type of genre – the syllogism. The question still remains open, however, whether after developing formal, logical ways of thinking individuals still preserve and use “pre-logical’’ empirical modes.

This question is known as a problem of “thought heterogeneity”, and it was much discussed since Lévi-Strauss (1966) from many points of view. Cognitive psychological research has contributed a lot to discussing this problem.

5. Psychological basis of reasoning modes

Cognitive psychological research (in connection with cross-cultural evidence and on its own) is interested in how reasoning, particularly syllogistic reasoning, is represented in the mind, that is, in what is the psychological nature of inference. A major question is whether formal logical reasoning is represented in the mind as a special component, or not.

5.1. Johnson-Laird’s “reasoning without logic”

Johnson-Laird since his early publications (Wason and Johnson-Laird 1972; Johnson-Laird 1983, 1986; Johnson-Laird and Byrne 1991) has addressed the problem of what he calls “inferential competence” and “inferential performance” (1986: 13). He denies the existence of “mental logic”, that is, of mental representations of inference-rule schemata reflecting logical formulae in the brain. Instead he proposes an alternative theory – “theory of mental models” – of deductive reasoning based on a “semantic principle of validity”. He claims that a psychologically plausible hypothesis is “reasoning without logic”, when solving syllogisms is based not on the use of logical rules but only on the content and truth of the premises.He suggests that reasoning without logic includes three steps:

a. interpretation of the premises by constructing a model which is based on truth conditions [that is on creation of a model which incorporates the information in the premises in a plausible way – I.D.],

b. formulation on its grounds of a semantically relevant conclusion, and

c. search for an alternative model which can prove the conclusion false.

If there is no alternative model which disqualifies the truth of the original conclusion, this conclusion is correct and can be accepted; if there is an alternative model, we proceed with selecting the most adequate model.

5.2. Deductive or inductive reasoning?

Another important aspect of the discussion about modes of reasoning in natural language concerns the question whether such reasoning is carried out in an inductive or in a deductive way. Moore (1986) claims the absolute priority of inductive over deductive reasoning, because deductive reasoning involves only the form of the argument, whereas inductive reasoning does not separate form from content, and content is dominant. From this position, he re-examines the conclusions of cross-cultural research (Luria, Scribner & Cole, etc.) He argues that “inability” of non-schooled villagers to deal with syllogisms is only apparent: they simply refuse to restrict inference to form only, and go with content, that is with their knowledge of the world. So, when they say that they cannot answer a question posed by a syllogism, this refusal implies a valid conditional argument (Moore 1986, 57): (7) If I could tell, I would have seen. I did not see. Therefore, I could not tell.

With the scheme: If p, then q. Not-q. Therefore, not-p. So, though the informant does not give an answer for the syllogism, it is due to his refusal to play logical games, a refusal which in itself gives no evidence for Luria’s claim that the individual cannot think deductively. Since there is no formal technique for description of inductive reasoning, it only looks that it has no rules. But such rules of inference exist; they include checking the content of a syllogism through worldly experience and [due to their cultural conventions of “politeness”-I.D.] not discussing issues outside their competence. This conclusion is very similar to Johnson-Laird’s position about creating a relevant model. In this case a model cannot be created because of the absence of reliable information.

In contrast to this inductive approach, Wilson and Sperber (1986) advocate the dominance of the deductive resolution of inference and relevance. They regard deductive inference by formal schemata as crucial for working with certain types of information, namely when the amount of explicitly presented information is deliberately reduced in communication. This position is compatible with the assumption that the deductive form of reasoning is not only part of mental representation, but is a dominant strategy in certain types of tasks.

So cognitive psychology, recognizing the existence of two modes of reasoning, still does not give a uniform answer on the question of “heterogeneity of thought”. Neurological experiments, however, help to shed light on this problem.

6. Neurological research: brain hemispheres and mode preferences

The abilities of literate adults to use both reasoning patterns were tested in unique experiments in the Sechenov Institute of Evolutionary Physiology, St. Petersburg, Russian Academy of Sciences, by Professor V.L. Deglin, a distinguished scholar in the area of functional differences of the hemispheres of the brain, and author of numerous books devoted to different aspects of the brain’s functions. This research was started by his supervisor, colleague and co-author, Professor L.Y. Balonov.

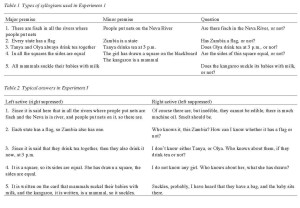

The experiments on syllogism-solving were part of a larger program of investigation of the contributions of the hemispheres to language production. The goal of the experiments presented here was to discover the contribution of the left and right hemispheres to solving syllogisms, by testing subjects’ performance when either their left or right brain is temporarily not functioning because of transitory suppression (Chernigovskaja and Deglin 1990, Deglin 1995). The group included 14 right-handed individuals of both sexes, all with secondary and some with university education. Each person was tested three times: before electroshocks (control investigation), after right hemisphere suppression, and after left hemisphere suppression. The study tested solving of two types of syllogisms (including motivation for the reply):

a. those with true premises (with both familiar and unfamiliar content – experiment 1), and

b. syllogisms with false premises (experiment 2).

6.1. Experiment 1: solving true syllogisms

The types of syllogisms are presented in Table 1, and the types of responses in Table 2.

In the control group, subjects gave predominantly theoretical answers (12 of 14), which could be expected, since all the subjects were educated within the culture in which syllogisms exist. Only two subjects gave empirical responses (in accordance with their experiences and beliefs) to some syllogisms, like the following in response to N.1: ” everybody knows that there is smelt in the Neva”, or the following in response to N.3: ” no, they do not drink, one drinks tea in the morning”. Empirical responses were extremely rare in the control group.

With right hemisphere suppression (left active) there was an even more pronounced tendency for usage of a theoretical mode: though the same number of subjects as in the control group (12 of 14) used the theoretical mode, all the tasks were solved more

readily, without hesitation, and with much more assurance than in the control investigations. In justifying their answers, the subjects referred spontaneously to the contents of the premises.

With left hemisphere suppression (right active) there was a strong difference from the previous cases. The number of empirical answers dramatically increased: 11 subjects of 14 used them. Some subjects even gave only empirical answers without using theoretical answers at all. In comparison with the control group, where only some syllogisms, usually those with strongly familiar or strongly unfamiliar content (e.g. 1, Table 1), were given empirical answers, here all syllogisms independently of the type of content (familiar-unfamiliar) were given empirical answers. However there was some difference in the statistical distribution of responses to syllogisms with familiar and unfamiliar content: in syllogisms with unfamiliar content the number of empirical answers was substantially lower. The subjects’ behaviour in using the modes was also different: empirical answers were given quickly and with assurance, whereas theoretical answers were given with difficulty and hesitations.

Experiment 1 demonstrated that one and the same person solves one and the same task differently in different states. The type of answer depends mainly on which hemisphere is active, and to some extent on the familiarity of the content of premises. The experiment showed “that within our culture, under usual conditions the “right-hemisphere” mode of thought [empirical mode – I.D.] is not drawn to syllogism solving” (Deglin 1995: 23-24).

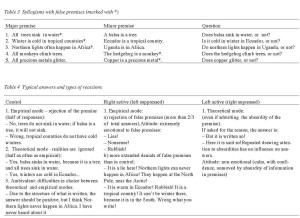

6.2. Experiment 2: solving syllogisms with false premises

6.2. Experiment 2: solving syllogisms with false premises

The types of syllogisms for this experiment are presented in Table 3 and the types of responses and typical reactions in Table 4. The control group gave three types of responses. Predominantly (2/3 of answers) empirical responses were used – rejection of the false premise or refusal to solve the syllogism. But there were also theoretical answers where irrelevance of the premises’s content to reality was ignored: “Yes, balsa sinks in water, because balsa is a tree and all trees sink in water”. In some case answers were ambivalent: the subjects were hesitant which of the strategies to use – the ftheoretical one, following the rules of syllogism but ignoring the false premise, or an empirical one, pursuing the truth: “Must I answer so as it is written here? Then the hedgehog climbs trees. But it does not climb. It is not a monkey.”

With left hemisphere suppression there was very strong rejection of false premises (90% of answers): they refuted false premises with conviction with a strong emotional reaction, extreme indignation, and much more extended denials (see Table 4).

With suppression of the right hemisphere, there was a dramatic change: the number of theoretical answers more than doubled, and the number of empirical answeres strongly decreased, with some individuals not using them at all. The subjects who followed theoretical answers did not pay any attention to the falsehood of premises (relying instead on the authority of what is “said’ or “written”), and proceeded to work with the information given to them. As a result there were absurd conclusions, derived in accordance with correct rules of formal logic. The emotional attitude radically changed – the subjects did their task calmly, with confidence, neglecting the absurdity of the premises.

So these neurological experiments demonstrated that the activated right hemisphere utilizes predominantly the empirical mode, whereas the activated left hemisphere utilizes predominantly the theoretical mode. Thus both mechanisms of reasoning are present in the brain simultaneously, both of them can be used, but each of them is controlled by a different hemisphere. The choice of strategy depends on the content of the issues discussed: issues with familiar content referring to everyday activities are discussed in the empirical mode, whereas issues with unfamiliar content are solved in a theoretical mode. These results explain the fact mentioned in much cross-cultural research that often educated subjects use both strategies. And these results give counterevidence to Johnson-Laird’s claim that formal reasoning is not represented in the mind.

The results of the neurological experiments are congruent with the peculiarities of functioning of the hemispheres: the right hemisphere operates cognitively with unified configurations (in this case with familiar scripts), whereas the left one processes discrete items (Witelson 1987) – in this case with the rules of formal deduction. This can raise a question whether the syllogism constitutes a script with a content (as was assumed in the discourse theory of reasoning) or is only a system of formal rules, a “syntactic script” never tied to a definite content but only to a definite form. In my opinion, the latter understanding of the syllogism is much more plausible and is congruent with the linguistic functions of the hemispheres. Linguistically the right hemisphere is responsible for (among other things) the referential and semantic correctness of words, and the left hemisphere for their syntactic organization (Balonov, Deglin, Dolinina 1983).[ix] In the case of reasoning patterns, the right hemisphere appears to control the quality of information (e.g. the truthfulness of premises, testing them against the realities of the world and/or personal knowledge/experience), whereas the left hemisphere is responsible for the correctness of purely operational mechanisms (formal correctness of inferences).

7. Conclusion

Two reasoning patterns can be used in solving syllogisms: an empirical (prelogical, traditional) one and a theoretical (logical, formal) one. The first employs information from life experience, knowledge of realities, the second only the information contained in the syllogism.

Cross-cultural investigators (Lévy-Bruhl, Luria, Cole, Scribner, etc.) demonstrated that the theoretical mode is not available to individuals in traditional societies, who employ only the empirical mode; the theoretical mode becomes available to them after acquisition of minimal literacy and Western-type schooling. This discovery contradicts Piaget’s claim that the theoretical mode develops ontogenetically as an obligatory stage of cognitive development. Various explanations of the failure of adults in traditional societies to develop the formal way of reasoning (which they should, according to Piaget) were proposed. Scribner claimed that oral traditional cultures do not have a syllogism genre, and so make use only of the genres which are available to them; when they learn this genre they can work with it. Specialists in literacy (Ong, Olson) claimed that literacy alone is sufficient for formal thinking, but this consideration was not supported by Scribner and Cole, who investigated literate traditional cultures (Vai) with authentic literacy, but still without formal reasoning. So they claimed that Western-type schooling (of which literacy is only a part) is crucial for formal reasoning. Thus, contrary to Piaget’s ontogenetic explanation of sources of formal reasoning, scholars (Tulviste) explained it as a function of sociocultural demands (though acquired, as Piaget claimed only after a certain age).

Since literate schooled individuals possess both modes of reasoning, the question arises which of the modes is normally used – both (in which case there arises the issue of “heterogeneity of thought”), predominantly the theoretical one (as more efficient and compact), or predominantly the empirical one (as based on everyday information). Some cognitive psychologists (e.g. Johnson-Laird and Moore) claim that the traditional, semantic way of reasoning is responsible for reasoning processes and is represented in the mind, the formal being only a “performance” strategy. Others (Wilson and Sperber) stress the priority of formal reasoning. Deglin’s neurological experiments on functional differentiation of right and left hemispheres demonstrated that both strategies are present in the brain: the right hemisphere uses the empirical mode, whereas the left one uses the theoretical mode.

NOTES

i. Later researchers argued that this stage emerges at a much younger age.

ii. Later this position was strongly supported by Lévi-Strauss (1962).

iii. Lévy-Bruhl’s position was rejected by many psychologists, anthropologists and linguists of that time (among them Boas) who took it as a statement of the inferiority of ‘primitive’ cultures, and who argued that the intellectual apparatus of people in primitive cultures was absolutely identical to that of people in more advanced cultures, because the cognitive and linguistic abilities of any culture and of any language are equal.

iv. Luria’s research was based on Vygotsky’s theoretical position that consciousness is not given in advance, but is shaped by activity and is a product of social history.

v. Although Luria did his research in the 1930s, his monograph was not published in the original Russian edition until 1974.

vi. Test of memory and retrieval of the information.

vii. They were carried out in Africa in Senegal, among Wolof, in Liberia among Kpelle and among Kpelle and Vai, and also in Mexico among Mayan- and Spanish-speaking villagers, with results very similar to Luria’s and to each other.

viii. Luria’s own explanations were only partially accepted. The grounds for criticism differed. For example, Cole in his foreword to the English translation of Luria’s monograph (Luria 1976: xv) comments that Luria, adopting the Piagetian developmental framework, does not differentiate between the performance of individuals in different cultures and the performance of younger and older children within the same culture.

ix. Under the influence of Chomsky’s syntactically based approach to language, North American researchers generally ascribe all linguistic functions to the left hemisphere.

REFERENCES

Cole, M., J. Gay, J.A. Glick & D. Sharp (1971). The Cultural Context of Learning and Thinking. New York: Basic.

Cole, M. & S. Scribner (1974). Culture and Thought. New York: John Wiley.

Deglin V.L. (1995). Thought heterogeneity and brain hemispheres, or how syllogisms are solved under conditions of transitory suppression of one of the hemispheres (Manuscript).

Deglin, V.L., L.Y. Balonov & I.B. Dolinina (1983). The language and brain functional asymmetry. Proceedings of the Tartu State University, 635, Transactions on Sign Systems. XVI, 31-42 (in Russian).

Deglin, V.L. & T.V. Chernigovskaya (1990). Syllogism solving under conditions of suppression of either the right or the left brain hemispheres. Human Philosophy 16, 21-28. (in Russian).

Deglin, V.L. & M. Kinsbourne (1996). Divergent thinking styles of the hemispheres: how syllogisms are splved during transitory hemisphere supression. Brain and Cognition 31, 285-307.

Ennis, R. (1998). Is critical thinking culturally biased ? Teaching Philosophy 21/1, 15-33.

Foley, W.A. (1997). Anthropological Linguistics: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Green, D.R. (Ed.) (1971). Measurement and Piaget. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Inhelder, B. & J. Piaget (1958). The Growth of Logical Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence. New York: Basic Books.

Johnson-Laird, P.N. (1983). Mental Modes: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference, and Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson-Laird, P.N. & R.M. Byrne (1991). Deduction. Hove/ London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Kess, J.F. (1992). Psycholinguistics: Psychology, Linguistics and the Study of Natural Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company,

Lévy-Bruhl, L. (1923). Primitive Mentality. New York: MacMillan.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966). The Savage Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Luria, A.R. (1976). Cognitive Development, Its Cultural and Social Foundations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Minsky, M. (1986). The Society of Mind. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Moore T. (1986). Reasoning and inference in logic and in language. In: T. Myers, K. Brown & B. McGonigle (Eds), Reasoning and Discourse Processes (pp. 51-66, Ch. 2), London: Academic Press.

Myers, T., Brown, K. & B. McGonigle (Eds.) (1986). Reasoning and inference in logic and in language. , London: Academic Press, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers.

Olson, D.R., Torrance N., & A. Hidyard (Eds.) (1985). Literacy, Language and Learning: The Nature and Consequences of Reading and Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality vs. Literacy: The Technologizing the of the World. New York: Methuen T.

Piaget, J. (1971). The theory of stages in cognitive development. In: D.R. Green (Ed.) Measurement and Piaget (pp. 1-11, Ch.1), New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schank, R. & R. Abelson (1977). Scripts, Plans, Goals, and Understanding: An Inquiry into Human Knowledge Structures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Scribner, S. (1977). Modes of thinking and ways of speaking: culture and logic reconsidered. In: P.N. Johnson-Laird & P.C.

Wason (Eds.), Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science (pp.483-500, Ch. 29), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scribner, S. & M. Cole (1981). The Psychology of Literacy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sharp, D., M. Cole & C. Lave (1979). Education and Cognitive Development: the Evidence from Experimental Research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child development 44, 2 (Serial #178).

Tulviste, P. (1979). On the origins of the theoretical syllogistic reasoning in culture and child. Quarterly Newsletter of the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition 1(4), 73-80.

Tversky, A. & D. Kahneman (1977). Judgement under uncertainty. In: P.N. Jonhson-Laird & P.C.Wason (Eds.) Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science (pp.326-337, Ch. 21). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1962). Thought and Language. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wason, P.C. & P.N. Johnson-Laird (1972). Psychology of Reasoning. London: B.T. Batsford LTD.

Witelson, S. F. (1987). Neurological aspects of language in children. Child Development 58, 653-688.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply