ISSA Proceedings 1998 – The Strategies And Tactics Used By F.W. De Klerk And Nelson Mandela In The Televised Debate Before South Africa’s First Democratic Election

No comments yet 1. Introduction

1. Introduction

1.1 Research questions and method used

Presidential debates began as an innovation in the 1960 election campaign between John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon. Since then televised debates have become a permanent and major part of the election process in the United States (Nimmo & Sanders 1981: 273). A similar debate took place between President Nelson Mandela (then, leader of the African National Congress, ANC) and the former President F. W. de Klerk, (then, leader of the National Party, NP) before South Africa’s first fully democratic election. It is highly probable that this debate – a first for SA – will set an example for similar debates. With the second election for the new SA in 1999, it seems apposite to do research on this trend-setting debate.

This study is a step in understanding and evaluating the processes involved in debating. From this analysis might come further discussions to improve the quality of debating and argumentation, in order to enrich democracy and allow citizens to make well informed decisions.

The focus of this paper is on the discursive logic or rational aspect of the message (Smith 1988:268), namely the verbal strategies and tactics. Therefore, this study endeavours to answer the following questions:

* Which verbal strategies and tactics have been used by the two debaters?

* Are there significant similarities and/or differences?

* Were they more “issue” or more “image” oriented?

In order to answer these questions the so-called Humanistic approach has been used. According to Smith (1988:269), this approach generates descriptive and inferential information, but its principal contribution consists of interpretations and criticism. In a certain sense this is a qualitative case study of a communication artefact (Watt & Van den Berg 1995:256; Marshall & Rossman 1995:124).

The following method has been used:

A verbatim transcription of the debate from video;

1. the strategies that Martel (1983:62-72) identified, as well as Rank’s model (Larson 1995: 15-21) have been used to identify and apply tactics and strategies;

2. a descriptive analysis (De Wet 1991:160) to indicate similarities or differences in the use of strategies and tactics;

3. an evaluation of the descriptive analysis.

1.2 Election background

The analysis must be viewed against the particular context of this debate. This election was not a normal one, but the first fully democratic election with a regime change. According to political scientist Theo Venter (1998) it was a so-called “designer” election, because the result was a forgone conclusion. The ANC’s take-over had been built on their high legitimacy because of the struggle against apartheid, where as Mr. De Klerk (hence: De Klerk) and the NP enjoyed deligitimation in the eyes of the masses. President Mandela (hence: Mandela) knew the ANC was the majority party and indeed they won the election gathering 62.7% while the NP got 20,3% of the votes. One can assume that Mandela’s goal was to reassure his supporters, or simply to avoid doing anything that might jeopardise their support.

De Klerk, on the other hand, wanted a strong as possible opposition against the ANC: “We need a balance of power. There is only one party (NP) which can form the balance of power against the ANC”. Both of them knew beforehand that the ANC would win. The margin of winning was in doubt.

1.3 Procedure

The debate started and ended with each of the debaters delivering a three-minute introduction and a four-minute closure respectively. Four panellists decided the issues that had been debated. They asked in alternative sequence four questions to Mandela and four to De Klerk. For each question each had two minutes to answer; after which each one had 1 minute for rebuttal.

It needs to be mentioned that De Klerk used 4109 words at an average of 133 words per minute or 406 words per answer. Mandela used 2598 words at an average of 84 words per minute or 253 words per answer. Mandela used 37% fewer words than De Klerk. Mandela talked slower, but in fourteen instances he didn’t use the full time that he was allowed to: 4,45 minutes were not used. (Figure 1)

At least two interpretations are possible: De Klerk can be regarded as more knowledgeable and Mandela as not that knowledgeable or Mandela may be more concise and succinct. It was probably a strategically decision: De Klerk would like to give the image of the rational debater that goes into specificity, because he realised that with the NP’s past record he should have done as much as possible to sell his New NP. Mandela would give the image of the frontrunner who does not need to do a lot of explaining. With this cryptic background the relational strategies can be discussed.

2. Relational Strategies

The relational strategies refer to those dominant modes of conduct intended to influence the audience’s perception of the candidate’s personality, and can be directed toward either the opponent, the panellists or the audience itself (Martel 1983:62). In this debate the two men mostly address the panellists and spoke only three times directly to each other.

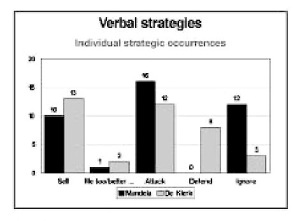

According to the descriptive analyses the following relational strategies have been used:

Sell your case, which is realised in the form of a verbal testimonial and also in the stating of the party’s policies.

“Me too …. me better” is a strategy where the candidate identifies himself with some of the opponent’s goals, but persuades viewers that his party is better qualified or equipped to carry them out.

Attack the opponent’s arguments, evidence and/or reasoning by demonstrating that they are invalid, erroneous, or irrelevant to weaken the opponent’s case.

Defend, or rebuild, by introducing new and additional evidence and/or reasoning to further substantiate your arguments or the response after being attacked.

Ignore means paying little or no heed to the opponent’s attacks or even panellist’s questions.

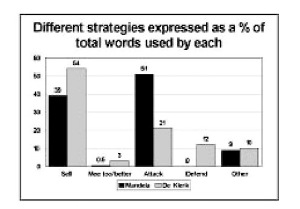

Other refers to any other information that are mere formalities, or general aspects that are not related to the parties’ distinct policy or image issues. (Figure 2 & 6)

2.1 Sell

Selling normally is appropriate if the candidate’s policy or credentials are not known or questioned. Thus, selling was the strategy that De Klerk used the most to explain the policies of the so-called New NP. He knew that he had to wipe out the image of the “old” NP and to fill their minds with the spirit and views of the New NP. Mandela knew that it was not necessary to sell a lot, because the outcome in the ANC’s favour was secured. Therefore De Klerk’s words were more selling orientated while Mandela’s were most frequently simply stating his party’s position:

(1)

Mandela:

“The ANC is committed to national reconciliation and to nation building. There is no organisation in this country, which has issued a statement to compare with the Freedom Charter, which is the most devastating attack on all forms of racialism. We have come out with a clear program to ensure a better life, to built houses, to offer employment, to provide free quality education. We are going to address these problems and restructure the police force, so that it could be a community police.”.

(2)

De Klerk:

“It is a new party. It is a party, which has renewed itself from within. It was an internal process. We cleansed ourselves from within. .. This New NP is a growing party. We believe in sound values. .. We believe in Christian norms and standards. We believe in free enterprise. We believe in universal human rights and feel that the bill of rights needs to be strengthened. We believe in religious freedom and we care about the needs of our people. We know many people are suffering. We must accept the challenge to fight hunger, to fight poverty; to ensure that more jobs will be created; to build homes for the homeless; to improve the quality of education. We have accepted it as a party, and we will work together with all those who also stand for that.”

2.2 Me too…. Me better

This strategy, which is a special kind of selling, was only used three times. De Klerk indicated two times that they will realise the promises better than the ANC:

(3)

“We also promised houses, better education, better health facilities and more jobs. The real test is who has a plan, which can achieve it? And I say the NP has a plan, which can work, because we can only achieve that if we have dynamic economic growth. And we can only have economic growth if we get investments. And we’ll only get investments and new factories being build and increased economic activity, if we follow economic policies, which are in step with our policy, because our policy is in step with the economic policies, which have succeeded across the world. The ANC’s policy is riddle with that which has failed, clinging to nationalisation. You will not get investments if that is the case. Therefore, we will have to generate wealth, and that is the only way.”

Mandela used it once when he mentioned that they “will be able to use the country’s resources in a more efficient manner and to prevent the corruption, which is so endemic in the NP Government”.

2.3 Attack

Attack was the most used strategy by Mandela. He used it 16 times and De Klerk 12 times (Figure 3). The analysis shows that Mandela succeeded in keeping De Klerk on the defensive, while Mandela himself didn’t defend at all. It was easier for him to attack De Klerk and the NP’s record, because they made the mistakes in the past. He even mentioned in one reply that he still could not vote, in spite of the fact that the election took place less than two weeks after this debate!

The nature and content of the attack differ substantially between De Klerk and Mandela. Mandela didn’t attack any policy issue as such, but focused nearly all of his attacks on the ethos or moral character of De Klerk. He also attacked the NP’s campaign tactics and crucial mistakes of the past. Except for a few times, his attacks were mostly short without much detail and at times without supporting evidence:

(4)

Mandela:

“He is less than candid in putting facts before the public”. (Repeated 3 times in varied forms.)

(5)

“This is the reply of a man who is not used to address the basic needs of the majority”

(6)

“This document is full of the most scandalous, outrages, racist allegations, where they say the slogan of the ANC is Kill the coloured. Kill the Boer! I challenge Mr. De Klerk to renounce that statement now (De Klerk: “I have last night.”), if he is less than candid. Last night when you knew you are coming to this debate.”

(7)

“They used state funds in order to finance the murderous activities of the IFP (Inkhatha Freedom Party).” De Klerk focused his attacks, except for a few other aspects, mostly on policy issues: the economic policy of the ANC, their clinging to nationalisation, the intimidation in their campaign, their lack of experience and the corruption in former homelands by two men that were on their candidates’ list. De Klerk’s attacks were in more detail, but were sometimes phrased in an indirect manner, which softens the attack:

(8)

De Klerk:

“And the Goldstone commission, when it brought out its report, I immediately acted. Can the ANC say the same with regard to people who have been implicated by the Goldstone commission? They are high on the ANC’s candidates’ list.”

(9)

“I didn’t have to intervene to get a coloured person appointed into an important position in the Western Cape as Mr. Mandela had to do…. I don’t have a R150 000.00 fine against me in the NP for intimidation as the ANC now has.”

(10)

“I am very glad that we are going to have a government of National Unity, because it is clear that our experience will be absolutely essential if we want to have good government in SA.”

(11)

“The ANC’s policy is riddled with that which has failed. Clinging to nationalisation, … stronger government intervention and more centralised control. Those policies will not succeed in generating wealth… Their plan will cost 70 billion Rand … Income taxes will be doubled; 12,000 new MK’s will be admitted to the defence force. The defence budget will rise and not decrease.”

2.4 Defence

With his standing in the polls one could expect that De Klerk would have done the most defending. Although a candidate who defends a lot seems guilty, defending is of the utmost importance when a decisive issue has been attacked (Martel 1983:67). Except for two counter statements (see 3.1.9), Mandela declined to react on the attacks to secure a degree of immunity. By making accusations where De Klerk’s credibility was at stake, Mandela succeeded to keep De Klerk on the defensive.

The nature of de Klerk’s defence, which tried to give as much detail as possible, can be illustrated with the following examples:

(12)

“Yes, the fact of the matter is that the Goldstone Commission was an initiative of the government. And I have constantly said if there’s any evidence of any involvement of any members of the security forces in the fomenting of violence, then it must be reported to the Goldstone commission. And when it brought out its report, I immediately acted. Lastly, the report refers to a small group of people. Judge Goldstone went out of his way to emphasise that it is not the police force as such which is involve.”

(13)

“Mr. Mandela, our plan is on the table, and it has been accepted by the National Housing Forum… But let me say, Mr. Mandela, my comments were not the comments of a man who is less than candid, but of somebody with experience. Of somebody who sat in the cabinet and worked through budgets since 1978 and who knows how the economy works. I’m giving you the assurance when you share responsibility in that government you will realise that we have already cut the budget to the bone.”

De Klerk also defended the following issues: The accusation that they promote racial hatred, the funds to the IFP, the issue of accountability and handling of corruption and the fact that the Steyn-report wasn’t published.

2.5 Ignore

Mandela ignored all the attacks and even ignored crucial aspects of some questions. In the first question Mandela ignored a crucial issue on what should be done, because “almost 300 people died in political and criminal violence in this month alone”. Another example concerns Tim Modise’s question:

(14)

“Are the people going to feel safe on the streets after the government of National Unity has been selected? They want to know whether here will be a delivery of social services, given the strikes that had been taken place? Will violence be eradicated completely? Above that, will there ever be racial reconciliation?” The problem with such questions is that there are actually five issues to be covered, which gives any debater the gap to answer only those which suits him best. Mandela didn’t address the strikes issue or how they are going to deliver the promises. The only answer to the violence was that they would restructure the police to a community police (see 2.1).

Mandela chose to ignore all the attacks from De Klerk and rather reacted with counter attacks. This lack of responsiveness is often the strategy of the frontrunner (Martel 1983:68). And in this case even more so where there was no doubt about the outcome of the election. De Klerk reacted to most of the attacks except those attacks that Mandela launched at the end of his rounds.

3. Tactics

3.1 Forensic and substantial tactics

While strategies indicate the debater’s broad approach, tactics refer to the specific verbal behaviour on micro level. In other words, the strategies are realised through the tactics. Thus, the strategies and tactics are not mutually exclusive. According to Martel (1983:77) three interrelated categories embrace the tactical choices, namely physical, forensic, and tonal categories. In this analysis only the forensic or argumentative behaviour and a few crucial tonal tactics are investigated and not the non-verbal or physical tactics. The focus is thus on the verbal manner of couching the substance for maximum strategic advantage. No distinction has been made

between the forensic and the substance tactics, because the line between them is not always clear.

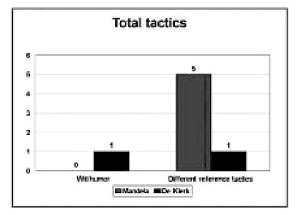

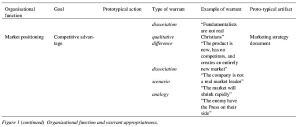

Tactics that have been used by the debaters, are the following: outright denial, turning the tables, shotgun blast, highlighting vagueness or evasiveness, quotable lines, tossing bouquets, timing tactics and surprising closing statements, apologies or confession, asserting counter arguments, direct questions, rhetorical questions, appeal to commonly held values, visual aids, and pseudo-issues and pseudo-clash. (Figure 4)

3.1.1 Outright denial

The tactic of denial was forcefully used four times by De Klerk and two times by Mandela.

(15)

De Klerk:

“I disagree with the analysis that the government is not dealing effectively with violence.”

(16)

“The answer is a frank, no. I’m white, but I am no longer the leader of a white party.”

(17)

“This government does not fund murderer’s activities.”

(18)

“I totally reject the accusation that the NP is racist.”

(19)

Mandela:

“And I don’t accept the explanation which the State President has given.”

(20)

”That is the false claim of building unity which my friend is making. I reject that totally.”

De Klerk followed the first two examples up with elaboration while Mandela gave the reasons before the conclusion. So, De Klerk handled his denials deductively and Mandela his inductively (Rieke & Sillars 1993:28).

3.1.2 Turning the tables

Mandela very effectively turned the tables after De Klerk mentioned the eight instances of violence which were, according to the Goldstone report, attributed to the ANC and IFP supporters. Mandela mentioned the fact that the report also referred to the involvement of policemen. One of the crucial tactical mistakes that De Klerk did was not to mention the involvement of the police and possible third force activities. This gave Mandela the gap to label De Klerk as not candid. He repeated this several times and it developed into a so-called “quotable line”. This happened in the very first round of the debate, which made it even worse for De Klerk. Had De Klerk at the same time acknowledged the facts, and also that he acted against the policemen, as a forewarning tactic, he probably would have been seen in a much better light.

3.1.3 Shotgun blast

This tactic is supposed to be a “forceful, concentrated multifaceted denunciation of the opponent’s character, record, position, or campaign” (Martel 1983:85). Both men used a variation of this tactic. De Klerk used it when he gave a rather detailed explanation of the implications of the ANC’s economic policies after he had an “independent investigation”, and in his rebuttal in the fifth round (see 3.1.9). Mandela ended the fifth round with a shotgun blast:

(21)

“Mr. De Klerk is alarmed because he is the leader of a party which even today is maintaining apartheid. He is spending 3 times more on education on a white child than he does on a black child. What is the reason if apartheid has died? He has not built houses for Africans for more than ten years. I cannot vote. There are 5 million people unemployed.”

3.1.4 Highlighting vagueness and evasiveness

Only Mandela used this tactic by labelling De Klerk five times as evasive, not listening and not transparent:

(22)

“It is of great concern those vague and starry eyed claims which have no bases what so ever.”

(23)

“We are dealing with somebody who either does not know what he is talking about. If he does know… he does not tell.”

The irony is that De Klerk could have accused Mandela of the same thing: Mandela didn’t reply on attacks and crucial aspects in questions put to him. He also didn’t explain how the ANC are going to realise their policies.

3.1.5 Quotable lines

Phrases that are used “to introduce or to end a line of argument can have more impact than other things said during the debate” says Martel (1983:88). Mandela labelled several times De Klerk as not candid. This, with the highlighting of evasiveness, became a quotable line:

(24)

“Mr. De Klerk is less than frank in making important statements on National issues.”

(25)

“He is less than candid in putting facts before the public”

(26)

“Mr. De Klerk is less than candid in analysing national issues” – several times.

3.1.6 Tossing bouquets

Mandela used this tactic by using the following verbal interaction:

(27)

“I am happy that we are working together… and that is what I am committed to in spite of all our differences that we have”.

(28)

“In spite of my criticism of Mr. De Klerk, sir, you are one of those I rely upon.”

(29)

“But we are saying, let us work together for reconciliation and nation building. I am proud to hold you hand for us to go forward.

(Mandela holds De Klerk’s hand.). Let us work together to end division and suspicion.”

For some this may be seem like hypocrisy: speaking from two mouths (Johannesen 1991:73). For other this may be brilliant tactics, because it suggests a very noble man: Although De Klerk is untrustworthy, not candid, does not know what he is talking about, evasive, still promote racist policies, etc, Mandela is willing to take his hand, forgive him and work with him to create nation building in SA.

3.1.7 Timing tactics and closing with a surprise

Three times Mandela saved his strongest attacks for the last response opportunity within a round. This allowed him to end strongly, since his arguments were to stand unrefuted. He made damning statements that couldn’t be responded to. This tactic is unethical (White 1991:143) and according to Martel (1983:90) this can be perceived as foul play since the opponent had no opportunity to respond (see examples at 3.1.3 & 3.1.10).

3.1.8 Apology

Considering the NP’s past, it was essential that De Klerk used this tactic twice during his last two speech encounters:

(30)

“One can never forget injustice, but you can forgive, and we need forgiveness.”

(31)

“We have admitted that our past policies led to injustice. We have apologised for that… We also want to rectify those injustices.”

3.1.9 Counter arguments

As mentioned earlier, Mandela didn’t defend, but he reacted only on two issues by using counter arguments, not immediately after they were raised. The two aspects were the ANC’s lack of experience and De Klerk’s opening words of the evening, which was not meant to be an issue:

(32)

“As State President it has been my privilege to lead the process which brought us to this historic moment. In that I have been assistent by leaders. Also Mr. Mandela, here, and I pay tribute to them. … I promised a new constitution through negotiation.”

In the fifth round where the question by John Simpson focused on the possibility that whites will no longer play a part in the political process, Mandela gave a counter statement by saying that “Everybody knows that negotiation is the result of the suffering of the masses of the people, supported by the international community”. In the seventh round he suddenly mentioned: “I started negotiations when I was in jail.”

Mandela stated in the third round and also at the very end that the “ANC is an organisation with more than 80 years of building national unity in this country”. This was to counter De Klerk’s reactions in the second round:

(33)

“My comments were not the comments of a man who is less than candid, they were the comments of somebody with experience. Of somebody who sat in the cabinet and worked through budgets since 1978 and who knows how the economy of the state works.” De Klerk also used this tactic in the form of counter evidence. After Mandela asserted that it was “the racist security police of the NP” who shot and killed those who have suffered and who “threw them in jail. Who turned our lives into nightmares”, he countered it with the following:

(34)

“Mr. Mandela can’t bluff with these accusations. The families of the victims of the necklace murderers which we had from supporters of his organisation. The people in the townships who are suppressed and intimidated by the SDU’s (Self-Defence Units), they know who are suppressing. The people whose houses have been burnt down, know who are the guilty ones, and the parents of the children whose lives have been ruined by the misuse of education by the ANC, know who cause the misery for their children.”

3.1.10 Direct questions and rhetorical questions

Mandela asked during the very last encounter of the debate:

(35)

“I would like to know from Mr. De Klerk, who was disciplined when 8 million (earlier Mandela mentioned R250.000) of taxpayers money was given to the IFP.” This could be viewed as unethical, because of the misquote and the unfairness, because De Klerk could not respond. Both made use of rhetorical questions. De Klerk used it when he asked:

(36)

“The real test is, who has a plan, which can achieve it? Can the ANC say the same with regard to people who have been implicated by the Goldstone commission?”

Mandela used it when he asked:

(37)

“Where is their housing plan? What is the reason for discrimination? What is the reason for not giving me the report?”

3.1.11 Appeal to commonly held values

De Klerk appealed to values twice:

(38)

“We believe in free enterprise, good family values, real peace, in reconciliation, Christian norms and standards, universal human rights, in a value system which has proven itself across the world. And that is bringing together all the people across the old divisions from all the population groups into our party. Colour has become unimportant. And that is giving impetus to our party which ensures that for those who believe in this value system which is in step with the successful part of the world, will become the dominant political factor.” Generally accepted values, when they are applicable to most segments of an audience, can motivate people in their everyday behaviour (Ross 1994:48).

3.1.12 Visual aids

Visual aids are not often used in debates, but can add spark to a dull exchange. Mandela’s tactic to show twice a copy of the document, served as visual proof of the campaign tactics of the NP where, according to Mandela, racial hatred had been promoted (see 2.3). It was used to give credibility to his attack especially at the very end where he showed it again.

Another dramatic use of a “visual aid” by Mandela was the handshake with De Klerk at the end: “I am proud to hold your hand for us to go forward”. Tactically this suggested that he is fair-minded, forgiving and visually demonstrating reconciliation, willing to “end division and suspicion”. This was probably one of the tactics that was mostly imprinted on the minds of the viewers.

3.1.13 Pseudo-clash and pseudo-issues

Pseudo-clash gives the impression that disagreement exists when it may not (Martel 1983:103). Mandela didn’t deny the words of De Klerk that there “has been very good co-operation between the NP and the ANC” to get the IFP to participate. Mandela, however, created pseudo-clash in mentioning the funds that were given to the IFP.

That was not the issue and De Klerk was also against it and stopped the covert action. Mandela went even further to make a connection between the money given to them and the murders that took place: “They used State funds in order to finance the murderers activities of the IFP”; an assertion without a warrant (Toulmin 1969:97-107, Freely 1990:152).

According to Martel (1983:103) a pseudo-issue “is a position taken by a candidate for selfish political gain which in reality is far less important than he implies – if not actually insignificant. He exaggerates the importance of weaknesses, normally because he has difficulty assailing its strengths.”

When De Klerk spelled out what the plan of the ANC would cost, Mandela turned it into a pseudo-issue by labelling De Klerk’s explanation as an alarmed man because “we have to devote so much resources to blacks whose concerns they (NP) don’t care for.” He also used this tactic when he mentioned:

(39)

“It is a false statement to suggest that any one individual started the negotiations. Everybody knows that negotiation is the result of the suffering of the masses of the people, supported by the international community.”

The question put to De Klerk focused on the issue whether the whites will play any role at all in the future. How it came to this stage was not important, but what would happen after the election when the ANC is in office, was. The use of this tactic is in sharp contrast with Mandela’s statement at the beginning: “I will resist the temptation to deal with issues which are unimportant”.

3.2 Tonal tactics

The tonal tactics refer to the general attitude or tone of their presentation to be consistent with their image goals and other strategies and tactics. Martel (1983:94) mentions four tonal aspects, namely controlling backlash, wit or humour, avoiding defensiveness and reference tactics. Three of these are applicable on this debate. Defensiveness has been dealt with under strategies (see 2.4).

3.2.1 Humour

The two men were very serious and no real wit or humour had been used during the debate. The nearest to that is in the words of De Klerk, which evoked a laugh from his studio supporters:

(40)

“If he thinks that he can save on the salary of politicians, enough, to solve the economic challenge which we have in SA, then he is in for a big surprise.”

3.2.2 Reference tactics

The reference tactics are also worth mentioning. De Klerk refer to Mandela as Mr. Mandela and he. This way of reference connotes both respect and distance (Martel 1983:97). Mandela also used Mr De Klerk and he, but on strategic moments he used other ways when he attacked De Klerk’s ethos or credibility:

(41)

“And what I find unacceptable is the fact that the President should misquote the reports. I don’t accept the explanation which the State President has given.” The implication is that a President of a country should be above misrepresentation.

(42)

“There is no organisation in this country as deceitful as the so called New NP of my friend on my left. It is actually promoting racial hatred. This is the false claim which my friend has made.” Strategically the choice of reference is effective: It is bad to have an opponent or enemy who deceives you and promotes racial hatred, but it is much worse if your friend does such unethical things.

(43)

“This is the reply of a man who is not used to address the basic needs of the majority of the population. It is quite clear that we are dealing with somebody who either does not know what he is talking about…” He moved from State President and my friend to somebody. This was a rather disrespectful way of addressing De Klerk. It, man and somebody were used to diminish the stature of his opponent (Martel 1983:97).

4. Issue Knowledge Versus Image Building

With the above strategies and tactics in mind, an answer can be given to the question which Zhu, Milavsky & Biswas (1994:302) ask in their article: Do televised debates affect image perception more than issue knowledge?

It is difficult to distinguish clearly between content that is issue related and content that is image related, because they are closely intertwined. For issue related content, I took any information that has to do with policy matters which the panellists put on the table: the dealing with violence, the realising of all the promises, the future role of whites; the handling of the non-participated IFP, the handling of accountability, the realising of racial reconciliation.

Aspects like campaign methods, trustworthiness of debaters, happenings in the past and conduct of followers, have been classified as image related. In these cases the image of De Klerk and the NP or Mandela and the ANC were at stake.

In De Klerk’s case he used 55% of his content for issue related aspects and Mandela only 26,5%. Of all the words that had been spoken only 40,7% had the slightest relation with the candidates’ position on policy issues. (Figure 6)

A conclusive answer about the effect on the viewers cannot be given, but according to the analysis, the main focus was on the images of the candidates and their parties. The general perception is that no substantial or new information about their issue positions, especially in the case of Mandela, had been given. This

corresponds to Kraus & Davis’ (1981: 275) view on other debates. The reason may be found in the fact that Mandela knew the ANC would win the election by a large majority. The nature of the information contributed little to new issue knowledge: mostly vague and very generally put. At best they offered condensed statements, without the practical implications or the operasionalising of the policies.

5. Ranks’s Model Of Persuasion

According to Rank (1976), on the strategic level, a persuader/debater can choose to intensify his own good points and/or the weak points of the opponent; and to downplay their own weak points and/or the opponent’s strong points. The tactics to realise these strategies are repetition, association and composition to intensify aspects; and omission, diversion and confusion to downplay certain aspects.

Mandela especially focused on the intensifying of De Klerk’s weak points by using all three tactics: He used repetition by mentioning at least ten times that De Klerk was not candid, frank, trustworthy or did not know what he was talking about. (Whether these accusations are true or not, is not the issue here.) He further associated De Klerk and the NP with the bad things of the past, namely racial hatred, injustice, lack of accountability and funders of murderers’ activities.

Mandela also used the tactic of composition. Three times he attacked De Klerk at the end of a round, knowing that it will stick in the memory of the audience, because there were no counterarguments or defence (see 3.1.7).

Mandela further downplayed his party’s own weaknesses by omission and diversion. He didn’t respond to the attacks that De Klerk had launched on his party: the R150,000 fine they got for intimidation; the connection of their economic policy with communism, the eight instances where the ANC and IFP caused serious violence, that their plan will cost 70 billion Rand the first year. He used diversion by sometimes focusing on irrelevant arguments (Govier 1992:146) and by attacking De Klerk’s character, called ad hominem (Pfau et al. 1987:141), when a policy issue should be addressed (see 3.1.13).

De Klerk intensified the NP’s strong points sometimes with repetition, but more with association. Although he mentioned twice the general philosophy of the NP and their appeal to commonly held values (see 3.1.11), he associated their economic policy with the successful economies in the world, and that their policies are associated with acceptable and ethical values.

De Klerk downplayed the ANC’s policy to associate it with “that which has failed” namely nationalisation and communism. He tried to downplay the police’s role in the violence by omitting it at first, but Mandela turned the tables on him. He also downplayed the past when he mentioned that the debate would be about the future and not the past and when he apologised for the injustice that had been done in the past. He did not use diversion or confusion. According to his values, this would be wrong (Schuurman 1996:208).

REFERENCES

Bitzer, L. F. (1981). Political Rhetoric. In: D. D. Nimmo & K. R. Sanders (Eds.), Handbook of Political Communication (pp. 225-248, (Ch. 8), Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Denton, R. E. (Jr.) (Ed.). (1991). Ethical dimensions of Political Communication. New York: Praeger.

De Wet, J. C. (1991). The art of Persuasive Communication. Kenwyn: Juta.

Freeley, A. D. (1990). Argumentation and Debate, Critical thinking for Reasoned decision making. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Govier, T. (1992). A Practical study of Argumentation. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Johannesen, R. L. (1991). Virtue ethics, Character, and Political communication. In: R. E. Denton, Jr. (Ed.), Ethical dimensions of Political communication (pp. 69-90, Ch. 5), New York: Praeger.

Kraus, S. & Davis, D. K. (1981). Political Debates. In: D. D. Nimmo & K. R. Sanders (Eds.), Handbook of Political Communication (pp. 273-296, Ch. 10), Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Larson, C. U. (1995). Persuasion: Reception and responsibility. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Marshall, C. & Rossman, G. B. (1995). Designing Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

Martel, M. (1983). Political Campaign debates: Images, Strategies and Tactics. New York: Longman.

Nilsen, T. R. (1966). Ethics of Speech Communication. New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co.

Nimmo, D. (1981). Ethical issues in Political Communication. Communication 6, 187-206.

Pfau, M., Thomas, D. A. & Ulrich, W. (1987). Debate and Argument, A Systems approach to Advocacy. Glenview: Scott, Foresman and Co.

Rank, H. (1976). Teaching about public persuasion. In: H. Dieterich (Ed.), Teaching and doublespeak. Urbana, Illinois: National Councel of Teachers of English.

Rieke, R. D. & Sillars, M. O. (1993). Argumentation and Critical decision making. New York: HarperCollins.

Ross, R. S. (1994). Understanding Persuasion. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Schellens, P. J. & Verhoeven, G. (1994). Argument en tegenargument, Analyse en beoordeling van betogende teksten. Groningen: Martinus Nijhoff Uitgevers.

Schuurman, E. (1996). What kind of strategies will be applicable in a Christian Political Party? In: Christian responsibility for political reflection and services: Institute for Reformational Studies, Christianity and Democracy (pp. 202-210, Ch. 22), Potchefstroom: Potchefstroom University for CHE.

Smith, M. J. (1988). Contemporary Communication Research methods. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Toulmin, S. E. (1969). The uses of argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Venter, T. (1998). Personal information given to author. Potchefstroom.

Watt, J. H. & Van den Berg, S. A. (1995). Research methods for Communication Science. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

White, R. A. (1991). Democratization of Communication: Normative Theory and Sociopolitical Process. In: K. J. Greenberg (Ed.), Conversations on Communication Ethics (pp. 141-164 Ch. 8), Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Zhu, J-H., Milavsky, J. R. & Biswas, R. (1994). Do televised debates affect Image perseption more than Issue knowledge? A study of the First Presidential Debate. Human Communicatio Research 20, 302-327.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply