ISSA Proceedings 2010 – A Doctor’s Argumentation By Authority As A Strategic Manoeuvre

No comments yet 1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Argumentation can play an important role in medical consultation. Central to medical consultation is a patient’s health related problem and a doctor’s medical advice, diagnosis and/or prognosis concerning this problem. Especially when such advice, diagnosis and/or prognosis can be expected to have a big impact on the patient, a doctor might assume the patient to be hesitant to immediately accept his claim(s). The doctor could attempt to overcome such hesitance by presenting argumentation. For instance, a doctor who advises a patient to drastically change his diet might attempt to make such advice acceptable by arguing “Your cholesterol level is too high”.

The context of a medical consultation does not just enable the doctor to present argumentation; it also affects the way in which the doctor provides this argumentation. Medical consultation is a regulated institutionalised communicative practice that is conducted in a limited amount of time. The health related problem that is central to such a consultation might be of vital importance to the patient, making the discussion of this problem potentially emotion laden. Furthermore, the doctor and patient differ in the amount of knowledge and experience they possess about the patient’s health related problem. As a result of these characteristics, the argumentation by a doctor in medical consultation typically differs significantly from that in, say, informal argumentative exchanges.

Because of a medical consultation’s limited amount of time and the fact that the doctor can be considered an authority on the patient’s health related problem, a doctor might decide to present argumentation by authority in support his claim(s). After all, the patient has acknowledged the doctor’s authority on medical knowledge by requesting a medical consultation, so it could be effective for a doctor to refer to this authority in support of his medical claim(s). On the other hand, a doctor’s argumentation by authority could essentially exclude the patient from the decision making process about the patient’s health related problem. This would limit the patient’s autonomy, reflecting a paternalistic form of the doctor-patient relationship that goes against the idea that medical consultation should be based on shared decision-making by the doctor and patient (see, on paternalism, Roter & Hall 2006; and, on shared decision making, Légaré et al, 2008; Frosch & Kaplan 1999). To what extent can a doctor’s argumentation by authority then be regarded as reasonable?

To determine the extent to which a doctor’s argumentation by authority in medical consultation can be regarded as reasonable, it is necessary to first provide a detailed account of a doctor’s rationale for presenting this kind of argumentation. Based on the extended pragma-dialectical theory, I shall provide such an account by analysing a doctor’s argumentation by authority as a strategic manoeuvre. Concretely, I shall, first, discuss the extended pragma-dialectical theory. Second, I shall provide a description of what I regard as argumentation by authority. Third, I shall examine a doctor’s argumentation by authority as a strategic manoeuvre, focussing on the doctor’s selection from topical potential, adaptation to audience demand and the presentational devices that he employs when presenting authority argumentation.

2. The extended pragma-dialectical theory

According to the extended pragma-dialectical theory, developed by Van Eemeren and Houtlosser (Van Eemeren, 2010; and Van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 1999; 2000; 2002a and 2002b), a discussion party always strategically aims at obtaining the dialectical goal of reasonably resolving a difference of opinion and, at the same time, at obtaining the rhetorical goal of resolving this difference of opinion in his own favour. To pursue these goals, the discussion party manoeuvres strategically. In other words, he simultaneously makes a selection from the topical potential, adapts to audience demand and uses particular presentational devices in each of his discussion moves to obtain his dialectical and rhetorical goals.

The term topical potential refers to the collection of issues that a discussion party could discuss at any particular point in an argumentative discussion (Van Eemeren, 2010, p. 95). The topical potential depends on the context in which the discussion is conducted and the discussion stage in which a discussion party wants to make a contribution. A discussion party selects from the topical potential in, for example, the argumentation stage by choosing a particular propositional content (from all possible propositional contents available in the context at hand) for the argument that is to be presented and choosing to give this argument a particular justificatory force (from all possible justificatory forces available in the context at hand). A doctor might, for example, support a medical advice by choosing to refer to himself as an authority on the patient’s health related problem as the argument’s propositional content and choosing to give it the justificatory force that is captured in the premise “If an authority on the patient’s health related problem says X, then X is the case”.

In addition to selecting from the topical potential, discussion parties simultaneously try to adapt their discussion contributions to audience demand (Van Eemeren, 2010, p. 94). They attempt to adjust their moves to the opinions and preferences of their intended audience in order to create rapport with this audience. A discussion party’s audience consists at least of one interlocutor who acts, or is presumed to act, as the opposing or doubting discussion party.[i] The audience could also consist of a multiple audience, in which case the discussion party addresses not only his primary audience (consisting of the interlocutor(s) that he mainly wants to convince), but also of a secondary audience (consisting of the interlocutor(s) that he does not necessarily want to convince, but all the same listen to the discussion party) (see Van Eemeren, 2010). In a discussion between a paediatrician, a child patient and the patient’s parent, for instance, the paediatrician and parent might regard each other as their primary audience, while viewing the patient as their secondary audience.[ii] To convincingly adapt to audience’s demand, a discussion party will adjust his strategic manoeuvres in a way that optimally agrees with the (multiple) audience’s starting points.

For optimally conveying discussion moves, discussion parties use presentational devices in each and every discussion contribution (Van Eemeren, 2010, p. 94). Van Eemeren (2010, p. 120) states “Although in strategic maneuvering it may be more conspicuous which stylistic choice is made in one case than in another, cases that are stylistically “neutral” do not exists, so each choice always has an extra meaning”. Discussion parties use presentational devices – such as word choice, sentence structure and rhetorical figures – to achieve the rhetorical and dialectical goals that they pursue in the discussion stage at hand. Their use of presentational devices, in other words, strategically frames their selection from topical potential and adaptation to audience demand. For instance, a patient might indirectly justify his request for a medical consultation by stating “I read about it on the internet and they advise you to see your doctor if it doesn’t change in a fortnight”, rather than directly arguing “I’ve suffered continuously from it for a fortnight, so I’d like to get your advice on it”.

Although from an analytical point of view, a discussion party’s selection from topical potential, use of presentational devices and adaptation to audience demand can be analysed separately, in actual argumentative discourse, all three aspects work together at the same time. A discussion party selects to address a certain topic in his discussion contribution because of what he thinks the audience prefers in the context at hand by the stylistic means he deems most suitable in this context. Based on this idea, a doctor’s argumentation by authority will be reconstructed and evaluated in the remainder of this study. However, before starting the actual reconstruction and evaluation of a doctor’s argumentation by authority, let me clarify what I understand by such argumentation.

3. The argument scheme of argumentation by authority

To accurately reconstruct and evaluate a doctor’s argument by authority, it is necessary to provide a description of this kind of argumentation first. The standard pragma-dialectical theory provides a good starting point for this. In this theory, authority argumentation is regarded as a subtype of the argument scheme based on a symptomatic relation (see Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, p. 160; and Garssen, 1997, p. 11). A pragma-dialectical argument scheme denotes a conventionalised way of representing how the content of an argument relates to the content of the (sub)standpoint in support of which the argument is presented (see Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, p. 96; and 2004, p. 4). In symptomatic argumentation, this relation is such that the content of the argument is given as a sign for the acceptability of the standpoint (see Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, p. 97 and Garssen, 1997, pp. 8-14). The argumentation “She must be a doctor, because she wears a white coat” is an example of symptomatic argumentation. In this argumentation, the discussion party (rather simplistically) regards “wearing a white coat” as a sign of “Being a doctor”.

In subtypes of argument schemes, the pragma-dialectical main types are used in a specific way. The subtype’s soundness conditions are, therefore, specifications of the soundness conditions for the corresponding main type. A discussion party who uses authority argumentation, for example, presents the agreement of a supposed authority with the discussion party’s standpoint as a sign of the acceptability of this standpoint (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, p.163; Garssen, 1997, p.11; and Schellens, 2006, p.6). It takes the form “He must be ill, because the doctor said he was and doctors are credible authorities on diagnosing people’s illnesses”. Authority argumentation is consequently considered to be a subtype of symptomatic argumentation. According to Van Eemeren (see 2010), one of the soundness conditions for authority argumentation is that the authority referred to in the argumentation is recognised as pertinent to the issue under discussion.[iii] This condition can be regarded as a specification of the soundness condition that applies to all symptomatic arguments, namely that the symptom mentioned in the argument is necessary for that which is mentioned in the standpoint.

Example (1) illustrates how a discussion party can use authority argumentation in actual practise. In this example, a paediatrician (D) discusses the diet of a child patient (C) with the patient’s mother (M) and father (F). The child patient is a little boy suffering from asthma.

Example (1)

Excerpt of an argumentative discussion between a paediatrician (D), the mother (M) and father (F) of a child patient (C) who suffers from asthma (example obtained from the database compiled by the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research, my transcription and translation, original conversation in italics)

1 D: By the way, I have to say that, about his, about what he eats, I’m not really concerned to be honest.

(Ik moet trouwens zeggen, over zijn, over wat hij eet maak ik me niet zoveel zorgen eerlijk gezegd.)

2 M: No.

(Nee.)

3 D: Look, I can imagine that, as mother and father, you are concerned, but if I look at the way he’s grown. Well, one of those things you need for growing well is eating well …

(Kijk, ik kan me voorstellen dat als moeder en als vader je je zorgen maakt, maar als ik kijk naar hoe hij gegroeid is. Nou één van die dingen die je nodig hebt om goed te groeien, is goed te eten…)

4 M: Yeah.

(Ja.)

5 D: So he has had, he has had a sufficient amount in the past few months, so…

(Dus hij heeft, de afgelopen maanden heeft hij genoeg gehad, dus…)

6 F: Yeah.

(Ja.)

7 D: In that respect, it isn’t the most necessary thing for me to say: well, you have to eat. A little [incomprehensible].

(Wat dat betreft is het ook niet het meest noodzakelijke vanuit mij om te zeggen: nou, je moet eten. Een beetje [onverstaandbaar].)

[…]

18 M: No, but yeah, things are sometimes being said about it and in the end you also think like: what should I do here? Right? One says this. The other that. And then you also think like:

(Nee, maar ja hè, er wordt wel eens wat over gezegd en op het laatst denk je ook van: wat doe ik hier nou? Hè? De één zegt dit. De ander dat. En dan denk je ook van:)

19 D: It’s also good to come here then.

(Dan is het ook goed om hier te komen.)

20 M: “I’ve had enough.” You just don’t know what you have to do in the end.

(“Ik ben het nou zat.” Je weet op het laatst niet meer wat je moet.)

21 D: No, that, I can imagine that and, erm, well, if you encounter problems with that again, just say “I’ve been to the pediatrician”…

(Nee dat, dat kan ik me voorstellen en, uhm, nou, als u daar weer problemen mee heeft, zeg maar gewoon “Ik ben naar de kinderarts geweest”…)

22 C: Eeweeeeeeeeee.

(Iewieeeeieeeee.)

23 D: I’ve studied for it, which is the case. And, erm, he said…

(Ik heb daarvoor geleerd, dat is ook zo. En, uhm, die heeft gezegd…)

24 C: Pfoof.

(Pfoef.)

25 D: “We do that this way” and …

(“Dat doen we zo” en…)

26 M: Just stop that [to child].

(Hou jij [kind] eens even op.)

27 D: And [incomprehensible] with evidence: he’s growing just perfectly, which is the most important issue.

(En [onverstaanbaar] met bewijs: hij groeit gewoon perfect, dat is het belangrijkste.)

28 C: Pfoof, lelelelele.

(Pfoef, lèlèlèlèlè.)

29 D: Haha, little tyke.

(Haha, mooi kereltje.)

In example (1), the doctor presents the standpoint that he does not believe it necessary to change the child patient’s diet (turn 7). The doctor states that he is not concerned about the patient’s diet (turn 1), indicating that the patient’s parents should not be either. He subsequently argues why they should not be concerned: the patient has grown well in the past few months, so he must have eaten well (turns 3 and 5). The mother nonetheless continues by indirectly expressing doubt about the doctor’s advice; she knows that people hold views that contradict the doctor’s advice and would be confused if she were confronted with them (turns 18 & 20). In reaction, the doctor presents his authority argument. He argues that it is good that he mother has come to him then (turn 19), because he is a paediatrician and has studied for providing medical advice on issues such as her son’s diet (turn 23). In other words, he uses authority argumentation by stating that “You should disregard other people’s advice on the matter of changing your son’s diet, because I say so and I am a credible authority on this matter (as I am a paediatrician and I have studied for it)”.

Instantiations of authority argumentation such as the one in example (1) are quite similar to appeals to ethos as described in the literature on rhetoric. In these authority arguments as well as in appeals to ethos, the discussion party refers to his own capacity or character to make his standpoint more acceptable. The rhetorical term ethos is, however, not only restricted to discussion moves by which a discussion party explicitly refers to himself as the authority on the issue under discussion, but the term ethos is also more generally applied to the impression a discussion party gives when presenting argumentation, for instance, by his overall fluency. Because of this difference and because the doctor in example (1), in principle, presents a statement by an authority as a sign of the acceptability of his standpoint, I prefer to think of the doctor’s reference to his authority in example (1) as an instance of authority argumentation.’

The instances of authority argumentation in example (1), difference from authority arguments in which a discussion party refers to the authority of a third party when presenting authority argumentation. Such an argument nonetheless relates in the same way to the content of the standpoint as the doctor’s authority argument in example (1); the unexpressed premise for both amounts to a statement like “X is a credible authority on Y”. These authority arguments, consequently, not constitute distinct subtypes of symptomatic argumentation in terms of the pragma-dialectical theory. To nonetheless denote the difference between the two, I propose to call them kinds of authority argumentation. I shall use the term argument from authority exclusively for the kind of authority argumentation in which the authority referred to is a third party, and the term argument by authority for the kind in which the authority referred to is the discussion party that presents the argumentation.

Distinguishing between these kinds of authority arguments helps to determine the strategic advantages of presenting authority argumentation. For each kind, it can be specifically determined how the authority argument furthers the discussion party’s purchase of his dialectical and rhetorical goals. Additionally, based on the distinction between the two kinds of authority arguments, the general soundness criteria can be specified for a particular context – thereby making them specific soundness criteria. For example, to evaluate when a doctor can soundly use an argument by authority in medical consultation, the soundness criterion that the authority referred to should indeed posses the professed authority (Van Eemeren 2010, pp. 202-203; Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, pp. 136-137; and Woods & Walton 1989, pp. 15-24) can be specified by reference to the qualifications that a doctor should have obtained before being able to practise medicine or a particular branch of medicine.

4. A doctor’s strategic use of argumentation by authority

Based on the distinction between the two kinds of authority argumentation, the doctor’s rationale for chooses to present argumentation by authority can be examined. What alternative strategic manoeuvres could a doctor have performed at the time that he chose to argue by authority? What are the strategic advantages of presenting an argument by authority?

To see what alternative strategic manoeuvres a doctor could have performed when he chose to argue by authority, the distinction between an argument’s propositional content and its justificatory force is useful. According to Van Eemeren and Grootendorst (2004, p. 144), single arguments can vary in the propositions that they consist of (their propositional content) and the relation that is expressed between the standpoint and the argumentation in them (their justificatory force). For example, in the argumentation “He must be ill, because the doctor said he was”, the propositional content consists of the proposition “the doctor said he was ill” (“X says Y”), while the justificatory force is captured in the argument’s unexpressed premise “doctors are credible authorities on diagnosing people’s illnesses” (“X is a credible authority on Y”). By presenting such argumentation, the discussion party chooses this particular propositional content for his argumentation from the topical potential that consists of every possible proposition that he can think of and he selects this particular justificatory force from the topical potential that consists of all the possible justificatory forces that he can think of.

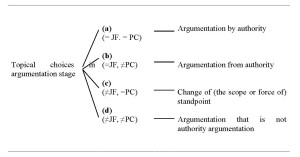

The idea that a single argument can vary as to its propositional content and its justificatory force means that there are, theoretically speaking, three alternative topical choices available to a doctor at the moment that he chooses to present an argument by authority. First, the doctor could have chosen to present an argument with the same justificatory force as the argument by authority, but with a different propositional content (figure 1b). The doctor then still chooses to present an argument based on the justificatory principle “X is a credible authority on Y”, but the “X” in this argument is not the doctor himself. An example of such an argument would be “He should go on a diet, because the genetic counsellor said that he runs a high risk to get diabetes”. This alternative, in fact, comes down to the kind of authority argumentation that I call argumentation from authority.

Figure (1)

A schematic representation of the topical choices available to a discussion party in the argumentation stage of an argumentative discussion. The topical choices are described in terms of the similarity with (“=”) and difference between (“≠”) the justificatory force (“JF”) and propositional content (“PC”) of the argument by authority (a) and of alternative strategic manoeuvres (b, c and d)

Second, a doctor could choose to present an argument with a different justificatory force than the argument by authority, but the same propositional content as the argument by authority (figure 1c). The doctor then chooses to present an argument based on the proposition “X says Y”, but not in combination with the justificatory principle “X is a credible authority on Y”. An example of such an argument would be “I was right about him all along, because I said that he runs a high risk to get diabetes”.

Note that, if the doctor were to present an argument of the kind (≠JF, =PC), he necessarily changes the (scope or force of the) standpoint in the argument by authority that he would otherwise have presented. This is due to the fact that, because the doctor chooses to use a different kind of justificatory force than in the argument by authority but also chooses to use a propositional content that is identical to the one in the argument by authority, an argument of the kind (≠JF, =PC) can only be logically valid if the standpoint that the argument supports is different from the one in the argument by authority. Concretely, in the example “I was right about him all along, because I said that he suffers from diabetes”, the justificatory force is captured in the premise “If I said he suffers from diabetes, I was right about him all along”, which means that the advanced standpoint has to be “I was right about him all along” to make the argumentation logically valid.

Third, a doctor could have chosen to perform a strategic manoeuvre that neither has the same justificatory force nor the same propositional content as the argument by authority (figure 1d). Opting for this alternative inevitably means that the doctor does not present authority argumentation. Instead, he could present other symptomatic arguments, causal arguments or analogy arguments. An example of such an argument would be “He should go on a diet, because he has a BMI of 32”.

For the purpose of discussing what the topical potential amounts to when a doctor chooses to present an argument by authority, the alternative strategic manoeuvre of presenting an argument of the kind (≠JF, =PC) is irrelevant. Arguments of the kind (≠JF, =PC) require a change of the doctor’s standpoint. Yet, by discussing the topical potential when a doctor presents an argument by authority, the topical potential that needs to be examined is the potential from which the doctor selects during the argumentation stage of an argumentative discussion. The standpoint that the doctor advances should therefore be considered as a given. This means that changing (the scope or force of) a standpoint cannot be regarded as a selection from the topical potential in the argumentation stage. At the moment that a doctor chooses to present an argument by authority, the topical potential that he selects this argument from hence consists of presenting an argument by authority (=JF, =PC), presenting an argument from authority (=JF, ≠PC) or presenting non-authority argumentation (≠JF, ≠PC).

What strategic advantage does a doctor’s choice for presenting an argument by authority have over the alternative strategic manoeuvres in the topical potential? Let me examine this, by means of the doctor’s argument by authority in example (1). Recall that the doctor in example (1) argues that the patient’s mother should disregard other people’s advice on the matter of changing her son’s diet, because he say so and he is a credible authority on this matter (as he is a paediatrician and has studied for it) (turns 19 & 23). Given that the doctor presented an argument by authority rather than performing the alternative strategic manoeuvres depicted in figure (1), it can be assumed that he thought this argument to strategically be the best selection from the topical potential available to him. To determine what the doctor’s rationale behind this could be, the audience demand that is placed on the doctor in this fragment of the medical consultation should be taken into account.

In the argumentative discussion in example (1), the mother, as a representative of the child patient, takes upon her the role of the doubting antagonist of the doctor’s advice. The doctor tries to take away her doubt by presenting argumentation in favour of his advice, which makes him the protagonist in this discussion. By indirectly presenting her doubt (in turns 18 and 20), the mother can be regarded as not only expressing her doubt about the acceptability of the doctor’s advice, but, in fact, also expressing her doubt about the doctor’s professional capabilities. If she were sure about the doctor’s professional capabilities, she would not have mentioned the different advices that others give. So, the audience demand that the mother places on the doctor in this part of the argumentative discussion consists of a request for further justification of the advice to refrain from changing her son’s diet as well as a request for further justification of why the doctor should be regarded as the credible authority on this matter.

In terms of the options in figure (1), just presenting argumentation from authority (figure 1b) or just presenting argumentation that is not authority argumentation (figure 1d) might take the mother’s doubts about the acceptability of the doctor’s advice away, but not necessarily her doubts about the doctor’s professional capability. Recognising that the audience demand that mother places on the doctor in this excerpt also implies doubt about the doctor’s professional capability next to doubt about the doctor’s advice indeed seems to request from the doctor that he presents argumentation by authority (figure 1a) in combination with other argumentation (so, argumentation from authority or argumentation other than authority argumentation). The argument by authority could rebut the mother’s doubt about the doctor’s advice (by indicating that the doctor is a credible authority, because he is a paediatrician and has studied for advising on medical issues) and the other argumentation could rebut the mother’s doubt about the professional credibility of the doctor (by taking away the criticism that makes his advice unacceptable, because he is a credible authority). Moreover, in this example, the doctor additionally refers to his earlier argumentation that the patient grows just perfectly (turn 27). The doctor thereby stresses that he has good reasons for giving the medical advice.

The idea that the doctor selects to present an argument by authority to adapt to audience demand in example (1) is reflected in the doctor’s use of presentational devices. In the consultation, the doctor strikingly refers to himself in the third person singular when presenting his argument by authority (in turns 21 and 23) and only continues in the first person singular to assure that he really studied for providing advices like the one about the child patient (in turn 21). Baring in mind that the medical consultation can be characterised as a cooperative conversational exchange, the doctor’s choice for these presentational devices can be explained by politeness considerations. In contrast with argumentative discourse such as a presidential debate, this means that the doctor can be expected to limit the mother’s potential face loss. Presenting his argumentation by authority in the third person makes it seem as though the doctor’s argument is not directed at the mother, but at the other people that give different advice. So, the doctor only indirectly counters the mother’s doubt about his professional capability to adapt to the audience by mitigating potential threats to the mother’s positive face (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 62).[iv] Indeed, he does so in a similar manner as the way in which the mother presents the doubts to the doctor herself (in turns 18 & 20).

By an analysis such as the one I have just provided for the doctor’s argumentation by authority in example (1), a doctor’s argument by authority in medical consultation can be analysed in general. It provides a systematic and context sensitive means to examine the strategic functions of this manoeuvre, which makes it possible to evaluate the doctor’s argument by authority in detail.

5. Conclusion

In medical consultation, argumentation may play an important role. A patient’s health related issues, and the doctor’s medical advice, are central to such a consultation. A patient’s (potential) hesitance about such advice could be overcome by the doctor when providing information about the patient’s health problems and argumentation in support of (parts of the) advised treatment(s).

The context of the medical consultation affects the manner in which the doctor and patient discuss health related issues. A doctor has to conduct the medical consultation in an efficient manner. During a consultations, he might not only have to provide the patient with a diagnosis, prognosis and/or medical advice, but also has to fully inform the patient about the reasons for the diagnosis, prognosis or advised treatment option(s), alternative treatment option(s) and consequences of refraining from treatment. This can be particularly complex given that the doctor’s medical claims about the patient’s health related issues might have a big impact on the patient and are, therefore, potentially emotion laden. What is more, the participants in a medical consultation characteristically differ in the amount of knowledge they possess about, and experience they have with, the health issues in question.

As a result of these characteristics of medical consultation, a doctor may present argumentation by authority. After all, the patient recognizes the doctor as an authority on health related problems by virtue of requesting a medical consultation. So, the doctor’s presentation of an authority argument in which he refers to himself as the authority could be quite effective.

By means of the analysis of an example of medical consultation taken from actual practice, I show that a doctor’s argument by authority could indeed constitute an opportune selection from the topical potential available to the doctor, which – when conveyed by appropriate presentational devices – a doctor could make to adapt to audience demand. Based on this analysis, I argue that the extended pragma-dialectical theory provides a systematic and context sensitive means to examine the strategic functions of the argument by authority in medical consultation.

NOTES

[i] This is recognised in the pragma-dialectical principle of socialisation, according to which an argumentative discussion is always an interactional process that is conducted between two or more interlocutors (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992, p.10).

[ii] Note that a discussion party does not necessarily have to consider the party that he directly faces as his primary audience. This is only the case if the discussion party regards that party as the audience that he first and foremost wants to convince. For example, in a televised presidential debate, the presidential candidates can be considered as constituting each others’ secondary audience, while those who watch the debate on television can be considered as the candidates’ primary audience (see Van Eemeren, 2010).

[iii] The other soundness conditions for authority argumentation that Van Eemeren (see 2010) list are that (1) the person referred to in this type of argumentation indeed possesses the professed authority, (2) the discussion parties in principle agree on referring to authority in the discussion, (3) the authority referred to is about a subject-matter that falls within the area of the authority’s expertise and (4) the authority is correctly cited at a place in the discussion where this is relevant.

[iv] According to Brown and Levinson (1987, p. 62), a person’s “positive face” can be defined as “the want of every member that his [or her] wants be desirable to at least some others”.

REFERENCES

Brown, P., & Levinson, C.S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language use. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Eemeren, F.H. van (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: A pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (1999). Strategic manoeuvring in argumentative discourse. Discourse Studies, 1(4), 479-497.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2000). Rhetorical analysis within a pragma-dialectical framework: The case of J. Reynolds. Argumentation 14(3), 293-305.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2002a). Strategic maneuvering win argumentative discourse: Maintaining a delicate balance. In: F.H. van Eemeren and P. Houtlosser (Eds.). Dialectic and rhetoric: The warp and woof of argumentation analysis. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic (pp.131-159).

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2002b). Strategic maneuvering with the burden of proof. In: F.H. van Eemeren (Ed.). Advances in pragma-dialectics. Amsterdam: Sic Sat (pp.13-38).

Frosch, D.L., & Kaplan, R.M. (1999). Shared decision making in clinical medicine: Past research and future directions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 17(4), 285-294.

Garssen, B.J. (1997). Argumentatieschema’s in pragma-dialectisch perspectief: Een theoretisch en empirisch onderzoek. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

Légaré, F., Elwyn, G., Fishbein, M., Frémont, P., Frosch, D., Gagnon, M.P., Kenny, D.A., Labrecque, M., Stacey, D., St. Jacques, S., & Weijden, T. van der (2008). Translating shared-decision making into health care clinical practices: Proof and concepts. Implementation Science 3 (2), 1-6.

Roter, D.L., & Hall, J.A. (2006). Doctors talking with patients / patients talking with doctors: Improving communication in medical visits. Westport: Praeger.

Schellens, P.J. (2006). ‘Bij vlagen loepzuiver’: Over argumentatie en stijl in betogende teksten. Nijmegen: Thieme MediaCenter.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply