ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Pragmatic Logic: The Study Of Argumentation In The Lvov-Warsaw School

No comments yet 1. The main question

1. The main question

Logical studies in Poland are mainly associated with the Lvov-Warsaw School (LWS), labeled also the Polish school in analytical philosophy (Lapointe, Woleński, Marion & Miskiewicz 2009; Jadacki 2009).[i] The LWS was established by Kazimierz Twardowski at the end of the 19th century in Lvov (Woleński 1989, Ch. 1, part 2). Its main achievements include developments of mathematical logic (see Kneale & Kneale 1962; McCall 1967; Coniglione, Poli & Woleński 1993) that became world-wide famous thanks to such thinkers as Jan Łukasiewicz, Stanisław Leśniewski, Alfred Tarski, Bolesław Sobociński, Andrzej Mostowski, Adolf Lindenbaum, Stanisław Jaśkowski and many others (see e.g. Woleński 1995, p. 369-378).

In ‘the golden age of Polish logic’, which lasted for two decades (1918-1939), ‘formal logic became a kind of international visiting card of the School as early as in the 1930s – thanks to a great German thinker, Scholz’ (Jadacki 2009, p. 91).[ii] Due to this fact, some views on the study of reasoning and argumentation in the LWS were associated exclusively with a formal-logical (deductivist) perspective, according to which a good argument is the one which is deductively valid. Having as a point of departure a famous controversy over the applicability of formal logic (or FDL – formal deductive logic – see Johnson & Blair 1987; Johnson 1996; Johnson 2009) in analyzing and evaluating everyday arguments, the LWS would be commonly associated with deductivism.[iii]

However, this formal-logical interpretation of the studies of reasoning and argumentation carried on in the LWS does not do full justice to its subject-matter, research goals and methods of inquiry. There are two reasons supporting this claim:

(1) Although logic became the most important research field in the LWS, its representatives were active in all subdisciplines of philosophy (Woleński 2009). The broad interest in philosophy constitutes one of the reasons for searching applications of logic in formulating and solving philosophical problems.

(2) Some of the representatives of the LWS developed a pragmatic approach to reasoning and argumentation. Concurrently with the developments in formal logic, research was carried out which – although much less known – turns out to be particularly inspiring for the study of argumentation: systematic investigation consisting in applying language and methods of logic in order to develop skills which constitute ‘logical culture’. Two basic skills that the logical culture focuses on are: describing the world in a precise language and correct reasoning. My paper concentrates on the second point.

The discipline which aimed at describing these skills and showing how to develop them was called “Pragmatic Logic”; this is also the English title of Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz’s 1965 book Logika pragmatyczna (see Ajdukiewicz 1974). The program of pragmatic logic may be briefly characterized as applying general rules of scientific investigation in everyday communication. This inquiry focused on the question whether the tools of logic can be used to educate people to (1) think more clearly and consistently, (2) express their thoughts precisely and systematically, (3) make proper inferences and justify their claims (see Ajdukiewicz 1957, p. 3). It should be added that this pragmatic approach to logic was something more fundamental than just one of many ideas of the school: it constituted the raison ď être of the didactic program of the LWS. Thus, the pragmatic approach to reasoning and argumentation had a strong institutional dimension: teaching how to think logically was one of the main goals of the school. The joint effort of propagating the developments of logic and exposing the didactic power of logic as a tool of broadening the skills of thinking logically may be illustrated by the passage from the status of the Polish Logical Association, founded on the initiative of Jan Łukasiewicz and Alfred Tarski in April 22nd, 1936.[iv] The aim of the association was ‘to practice and propagate logic and methodology of science, their history, didactics and applications’ (see The History of the Polish Society for Logic and Philosophy of Science).

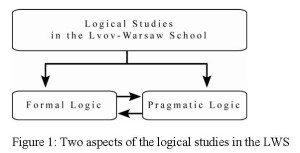

The inspiration for exposing this research field in the LWS comes from numerous publications on the origins of the informal logic movement and the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. In their writings informal logicians and pragma-dialecticians explained the phenomenon of revitalizing argumentation theory in the 1970s (e.g. Johnson & Blair 1980; Woods, Johnson, Gabbay & Ohlbach 2002; van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004; Blair 2009; Johnson 2009; van Eemeren 2009). They indicated a pragmatic need to evaluate arguments in the context of everyday communication as one of the main causes of this phenomenon. Thus, at the beginning of the modern study of arguments in the early 1970s we observe the ‘marriage of theory and practice’ in the study of logic (Kahane 1971, p. vii; see Johnson 2009, p. 19). In the case of the LWS this ‘marriage’ was realized by treating formal and pragmatic logic as two interrelated, and not competing, wings of inquiry:

From what has been said above, some similarities are noticeable between the approaches of the LWS and contemporary argumentation theory (including informal logic and pragma-dialectics). My paper aims at making those similarities more explicit, so I raise the question: what relation obtains between logical studies carried on in the LWS and the recent study of argumentation? The answer is given in three steps. In section 2 I present some elements of the conceptual framework of the LWS, which are relevant for exploring connections between the school and argumentation theory. Among those elements there are concepts of: (a) logic, (b) logical fallacy, (c) argument, and (d) knowledge-gaining procedures. These concepts are helpful for introducing the conception of (e) logical culture. In section 3 I discuss some crucial elements of the program of pragmatic logic, which was aimed at elaborating a theoretical background for developing knowledge and skills of logical culture. Among those elements there are: (a) the subject-matter of pragmatic logic and (b) its main goals. Section 4 explores some perspectives for the rapprochement of pragmatic logic with argumentation theory. In the paper I refer to the works of the representatives of the LWS, as well as to the tradition of the school that is continued to this day.

From what has been said above, some similarities are noticeable between the approaches of the LWS and contemporary argumentation theory (including informal logic and pragma-dialectics). My paper aims at making those similarities more explicit, so I raise the question: what relation obtains between logical studies carried on in the LWS and the recent study of argumentation? The answer is given in three steps. In section 2 I present some elements of the conceptual framework of the LWS, which are relevant for exploring connections between the school and argumentation theory. Among those elements there are concepts of: (a) logic, (b) logical fallacy, (c) argument, and (d) knowledge-gaining procedures. These concepts are helpful for introducing the conception of (e) logical culture. In section 3 I discuss some crucial elements of the program of pragmatic logic, which was aimed at elaborating a theoretical background for developing knowledge and skills of logical culture. Among those elements there are: (a) the subject-matter of pragmatic logic and (b) its main goals. Section 4 explores some perspectives for the rapprochement of pragmatic logic with argumentation theory. In the paper I refer to the works of the representatives of the LWS, as well as to the tradition of the school that is continued to this day.

2. The conceptual framework of the LWS

2.1. Logic

Due to its achievements in formal logic the LWS is usually associated with the view on logic as a formal theory of sentences (propositions) and relationships between them. This understanding of ‘logic’ (so-called ‘narrow conception of logic’) is dissociated from the ‘broad conception of logic’ that embraces also semiotics and methodology of science (see e.g. Ajdukiewicz 1974, p. 2-4). Both conceptions of logic are employed in the tradition of the LWS what is illustrated by the fact that in it ‘logical skills’ encompass not only formal-logical skills, but also skills which can be described as using tools elaborated in semiotics, e.g. universal tools for analyzing and evaluating utterances, and in the methodology of science, e.g. tools for developing and evaluating definitions, classifications, and questions occurring in scientific inquiry (see the Appendix A in Johnson 2009, p. 38-39). An interesting example of the broader account of logic can be found in Tarski (1995, p. xi). ‘Logic’ refers here to the discipline ‘which analyses the meaning of the concepts common to all the sciences, and establishes the general laws governing the concepts’. So, if such a notion of logic is introduced, its obvious consequence relies on treating semiotics (a discipline dealing with concepts) and the methodology of science (the one dealing with principles of scientific inquiry) as fundamental parts of logic[v].

Other members of the LWS gave substantial reasons for treating the methodology of science as an element of logic in the broad sense. Jan Woleński makes this point explicit by focusing on the methodology of science as a discipline that uses tools of logic in exploring the structure of scientific theories:

The philosophy of science was a favourite field of the LWS. Since science is the most rational human activity, it was important to explain its rationality and unity. Since most philosophers of the LWS rejected naturalism in the humanities and social sciences, the way through the unity of language (as in the case of the Vienna Circle) was excluded. The answer was simple: science qua science is rational and is unified by its logical structure and by definite logical tools used in scientific justifications. Thus, the analysis of the inferential machinery of science is the most fundamental task of philosophers of science (Woleński 2009).

Treating the methodology of science as part of logic is not that obvious for other research traditions because of the fact that methodology of science is seen as associated with philosophy rather than with logic. The broad conception of logic employed by the LWS includes semiotics and the methodology of science within logic, not within philosophy (Przełęcki 1971), which is one of the reasons why this treatment of logic is unique. Another distinctive feature of the LWS is the analytical character of philosophical studies – the very reason for introducing the broad conception of logic. For semiotics and the methodology of science are treated in the LWS as disciplines developing universal tools used not only in scientific inquiry, but also in everyday argumentative discourse where analyzing meanings of terms (the skill of applying semiotics) and justifying claims (the skill of applying the methodology of science) are also of use.

2.2. Logical fallacy

One of the consequences of employing this conception of logic is the LWS understanding of logical fallacies as violations of norms of logic broadly understood. These norms of logic in a broad sense are: (1) rules for deductive inference (formal logic), (2) rules for inductive inference (inductive logic), (3) rules for language use as elaborated in semiotics (syntax, semantics and pragmatics), and (4) methodological rules for the scientific inquiry. If these are the ‘logical’ norms, then consequently there are at least three general types of logical fallacies, i.e. (1) the fallacies of reasoning (also called the fallacies in the strict sense; see Kamiński 1962), (2) fallacies of language use (‘semiotic fallacies’), and (3) fallacies of applying methodological rules governing such procedures as defining, questioning or classifying objects (‘methodological fallacies’).

There are some difficulties with such a broad conception of fallacy. Two major objections against it are:

(a) This conception is too broad because it covers fallacies that are not violations of any logical norms strictly understood. For instance, it would be very hard to point to any logical norm, strictly understood, which would be violated in the case of improper measurement.

(b) The types of fallacies discerned from the viewpoint of the broad conception of logic overlap. For example, the fallacy post hoc ergo propter hoc may be classified both as the fallacy of reasoning and as a methodological fallacy. The fallacy of four terms may be classified both as a fallacy of reasoning and a semiotic fallacy, because of the fact that it is caused by the ambiguity of terms, and the ambiguity is classified as a semiotic fallacy.

Despite these and other objections, this conception was useful at least in determining a general scope of logicians’ interests in identifying fallacies. For example, affirming the consequent may be classified as a fallacy of reasoning, amphibology as a semiotic fallacy and vicious circle in defining as a methodological fallacy. This conception of fallacy was briefly presented to show that the conception of logical fallacy accepted by the majority of researchers of the LWS was much broader than that elaborated exclusively from the perspective of formal deductive logic.

2.3. Argument

Another element of the conceptual framework of the LWS is the concept of argument. Since most representatives of the LWS dealt basically with reasoning (e.g. elaborating very detailed classifications of reasoning), the conception of argument is related to the conception of reasoning. For instance, Witold Marciszewski (1991, p. 45) elaborates the definition of argument by associating it with a kind of reasoning performed when the reasoner has an intention of influencing the audience:

A reasoning is said to be an argument if its author, when making use of logical laws and factual knowledge, also takes advantage of what he knows or presumes about his audience’s possible reactions.

This definition is treated by Marciszewski as a point of departure for seeking theoretical foundations of argumentation not only in formal logic, but also in philosophy:

Therefore the foundations of the art of argument are to be sought not only in logic but also in some views concerning minds and mind-body relations including philosophical opinions in this matter.

These general remarks point to the need of analyzing argumentation not only from the formal-logical perspective, but also with bearing in mind the broader context of reasoning performed in any argumentative discourse. One of the ideas that may be used in analyzing arguments in a broader context is the conception of knowledge-gaining procedures. The procedures are treated in the LWS as components of argumentation.

2.4. Knowledge-gaining procedures

From the perspective of the broad conception of logic elaborated in the LWS, arguments may be studied by analyzing and evaluating the main knowledge-gaining procedures (or ‘knowledge-creative procedures’; see Jadacki 2009, pp. 98-100) and their results. According to Jadacki (2009, p. 99), in the Polish analytical philosophy the following knowledge-gaining procedures were examined in detail:

(1) Verbalizing, defining, and interpreting;

(2) Observation (the procedure consisting of experience and measurement);

(3) Inference:

(a) Deduction (proof and testing);

(b) Induction (statistic inference, ‘historical’ inference, inference by analogy, prognostics and explanation);

(4) Formulating problems;

(5) Partition, classification, ordering.

When we take argumentation as a process, it may be studied as a general procedure consisting of activities as those listed above. When one is dealing with argumentation as a product, the results of these procedures are to be analyzed and evaluated. The major research interests in the LWS focused on the following results:

Ad. (1) Concepts and definitions (as the results of verbalizing, defining, and interpreting);

Ad. (2) Observational sentences;

Ad. (3) Arguments understood as constellations of premises and conclusions:

(a) Deductive inference schemes;

(b) Inductive inference schemes;

Ad. (4) Questions (as results of the procedure of formulating problems);

Ad. (5) Typologies and classifications (as results of the procedure of ordering).

As Jadacki emphasizes, the procedure which was carefully investigated in the LWS, was inference[vi]. So, one of the most interesting results of the knowledge-gaining procedures are arguments understood as constellations of premises and conclusions.

2.5. Logical culture

The conception of logical culture joins two components: (1) advances in the logical studies (i.e. research in logic) are claimed to be applicable in (2) teaching critical thinking skills. According to Tadeusz Czeżowski (2000, p. 68):

Logical culture, just as any social, artistic, literary or other culture, is a characteristic of someone who possesses logical knowledge and competence in logical thinking and expressing one’s thoughts.

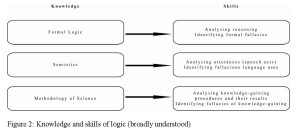

Thus, the term ‘logical culture’ refers both to the knowledge of logic (as applied in using language and reasoning) and to the skill of performing commonsense and scientific reasoning (Koszowy 2004, p. 126-128). Logic broadly understood elaborates tools helpful in sharpening the skills of the logical culture. The general areas of its application are illustrated by Figure 2:

We may here observe that some skills characteristic of the person who possesses logical culture are also substantial for the two normative models in the study of argumentation: (a) an ideal of a critical thinker in the tradition of teaching informal logic in North America, (b) the ideal of a reasonable discussant in a pragma-dalectical theory of argumentation.

3. The program of pragmatic logic

The concept of logical culture as presented in the previous section is here a point of departure for introducing Ajdukiewicz’s program of pragmatic logic. The term ‘logical culture’ denotes both knowledge of logic and skills of applying this knowledge in science and everyday conversations, whereas the term ‘pragmatic logic’ refers to a discipline aimed at describing these skills and showing how to develop them.

The program of pragmatic logic is based on the idea that general (logical and methodological) rules of scientific investigation should be applied in everyday communication. Pragmatic logic is a discipline aimed at applying logic (in a broad sense) in teaching and in everyday language use. So, two basic goals of pragmatic logic are: extending knowledge of logic and improving skills of applying it.

3.1. Subject-matter of pragmatic logic

Pragmatic logic consists of the analyses concerning:

(1) Word use: (a) understanding of expressions and their meaning, (b) statements and their parts, (c) objective counterparts of expressions (extension and intension of terms), (d) ambiguity of expressions and defects of meaning (ambiguity, vagueness, incomplete formulations) and (e) definitions (e.g. the distinction between nominal and real definition, definitions by abstraction and inductive definitions, stipulating and reporting definitions, definitions by postulates and pseudo-definitions by postulates, errors in defining).

(2) Questioning: (a) the structure of interrogative sentences, (b) decision questions and complementation questions, (c) assumptions of questions and suggestive questions, (d) improper answers, (e) thoughts expressed by an interrogative sentence and (f) didactic questions.

(3) Reasoning and inference: (a) formal logic and the consequence relation (logical consequence, the relationship between the truth of the reason and the truth of the consequence, enthymematic consequence), (b) inference and conditions of its correctness, (c) subjectively certain inference (the conclusiveness of subjectively certain inference in the light of the knowledge of the person involved), (d) subjectively uncertain inference (the conclusiveness of subjectively uncertain inference, logical probability versus mathematical probability, statistical probability, reductive inference, induction by enumeration, inference by analogy, induction by elimination).

(4) Methodological types of sciences: (a) deductive sciences, (b) inductive sciences, (c) inductive sciences and scientific laws, (d) statistical reasoning.

Since inference is one of the key topics of inquiry, in order to show that the program of pragmatic logic has a similar subject-matter to the contemporary study of argumentation, I shall discuss, as an example, Ajdukiewicz’s account of the ‘subjectively uncertain inference’.

According to Ajdukiewicz (1974, p. 120), a subjectively uncertain inference is the one in which we accept the conclusion with lesser certainty than the premises. It results from the fact that in spite of the premises being true the conclusion may turn out to be false. The instances of this type of inference are such that the strength of categorically accepted premises leads to a non-categorical acceptance of the conclusion. This is illustrated by the following example:

The fact that in the past water would always come out when the tap is turned on, makes valid – we think – an almost, though not quite, certain expectation that this time, too, water would come out when the tap is turned on. But our previous experience would not make full certainty valid (p. 120).

If we are to be entitled to accept the conclusion with less than full certainty, it suffices if the connection between them is weaker than the relation of consequence is. Ajdukiewicz deals with this kind of reasoning in terms of the probability of conclusion:

Such a weaker connection is described by the statement that the premisses make the conclusion probable. It is said that a statement B makes a statement A probable in a degree p in the sense that the validity of a fully certain acceptance of B makes the acceptance of A valid if and only if the degree of certainty with which A is accepted does not exceed p (pp. 120-121).

So, ‘a statement B makes a statement A probable in a degree p, if the logical probability of A relative to B is p’:

P1(A/B) = p.

Furthermore, Ajdukiewicz distinguishes the psychological probability of a statement (i.e. the degree of certainty with which we actually accept that statement) from the logical probability of a statement (that degree of certainty with which we are entitled to accept it). The logical probability is related to the amount of information one possesses at a given stage, because ‘the degree of certainty with which we are entitled to accept the statement depends on the information we have’. This claim is in accord with the ‘context-dependent’ treatment of arguments: argument analysis and evaluation done both in informal logic and in pragma-dialectics depends on the context in which arguments occur. Ajdukiewicz is aware of the fact that evaluating the logical probability of a given statement (P) depends on the actual knowledge of the subject who believes P. The following example confirms this interpretation:

If we know about the playing card which is lying on the table with its back up merely that it is one of the cards which make the pack used in auction bridge, then we are entitled to expect with less certainty that the said card is the ace of spades than if we knew that it is one of the black cards in that pack (p. 121).

This example gives Ajdukiewicz reasons not to speak about the logical probability of a statement ‘pure and simple’, but exclusively about the logical probability of that statement relative to a certain amount of information. Ajdukiewicz points to the fact that this relation between the logical probability and the amount of information we possess in a given context is clearly manifested in the following definition of logical probability:

The logical probability of the statement A relative to a statement B is the highest degree of the certainty of acceptance of the statement A to which we are entitled by a fully certain and valid acceptance of the statement B (ibid.).

This definition is helpful in giving the answer to the question: when is an uncertain inference conclusive in the light of the body of knowledge K? Ajdukiewicz’s answer is given in terms of the degree of certainty of the acceptance of the conclusion:

Such inference is conclusive in the light of K if the degree of certainty with which the conclusion is accepted on the strength of a fully certain acceptance of the premises does not exceed the logical probability of the conclusion relative to the premises and the body of knowledge K (ibid.).

This piece of Ajdukiewicz’s account of the subjectively uncertain inference shows that pragmatic logic deals with defeasible reasoning by looking for objective (here ‘logical’) criteria of evaluating defeasible reasoning. It clearly shows the tendency in pragmatic logic to analyze and evaluate not only deductively valid arguments, but also defeasible ones, as it is done in the contemporary theory of argumentation[vii].

3.2. The goal of pragmatic logic

The goal of pragmatic logic may be extracted from Ajdukiewicz’s view on logic treated as a foundation of teaching. This part of Ajdukiewicz’s analyses shows how important pedagogical concerns are for the program of pragmatic logic. It also explains why logic is called ‘pragmatic’.

For Ajdukiewicz ‘the task of the school is not only to convey to the pupils information in various fields, but also to develop in them the ability of correctly carrying out cognitive operations’ (Ajdukiewicz 1974, p. 1). This excerpt clearly explains why analysis and evaluation of knowledge-gaining procedures and their results is the main goal of pragmatic logic. If teaching students how to reasonably carry out major cognitive procedures (aimed at achieving knowledge) is one of the main purposes of teaching, then pragmatic logic, understood as a discipline aimed at realizing this goal, has as its theoretical foundation the description of the basic principles of knowledge-gaining procedures.

Ajdukiewicz’s crucial thesis is that logic consisting of formal logic, semiotics and the methodology of science constitutes one of the indispensable foundations of teaching. Logical semiotics (the logic of language) ‘prepares the set of concepts and the terminology which are indispensable for informing about all kinds of infringements, and indicates the ways of preventing them’ (Ajdukiewicz 1974, p. 3). The methodology of science provides ‘the knowledge of terminology and precise methodological concepts, and also the knowledge of elementary methodological theorems, which lay down the conditions of correctness of the principal types of cognitive operations, must be included in the logical foundations of teaching’ (p. 3). Ajdukiewicz gives an example of a science teacher, who informs students about the law of gravitation and its substantiation by explaining how Newton arrived at the formulation of the law:

When doing so he will perhaps begin by telling pupils that the said law was born in Newton’s mind as a hypothesis, from which he succeeded to deduce the law which states how the Moon revolves round the Earth and how the planets revolve round the Sun, the law which agrees with observations with the margin of error. That agreement between the consequences of the said hypothesis with empirical data is its confirmation, which Newton thought to be sufficient to accept that hypothesis as a general law (p. 2).

Thus, according to Ajdukiewicz, the role of the methodology of science in the foundations of teaching is revealed by the fact that crucial terms such as ‘hypothesis’, ‘deduction’ or ‘verification of hypothesis’ are in fact methodological and this is why they are useful in the process of achieving knowledge.

However, pragmatic logic is to be applied not only to scientific research or at school, but also to everyday speech communication. As Ajdukiewicz clearly states, pragmatic logic is not the opposite of formal logic, but both formal and pragmatic logic complement each other. Moreover, pragmatic logic is much more useful for the teacher, who aims – among other things – at training students to make statements that are relevant, unambiguous and precise, which is ‘one of the principal tasks of school education’ (Ajdukiewicz 1974, p. 3).

4. Pragmatic logic and argumentation theory: towards bridging the gap

The overview of the concepts of logic, logical fallacy, argumentation, logical culture, pragmatic logic, subjectively uncertain inference and the logical foundations of teaching gives support for the claim that in the LWS and in argumentation theory there are similar tendencies of crucial importance. One of the issues is that the two disciplines share in fact the same subject-matter. To show this in detail, however, would require further inquiry.

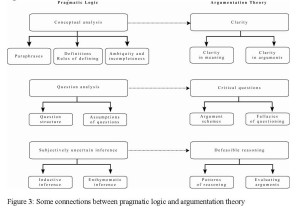

Future research should also answer the question of how the main ideas of pragmatic logic may be of use in the analysis, evaluation and presentation of natural language arguments. Research on such applicability of pragmatic logic may focus on the analysis of those components of the program of pragmatic logic which also constitute the subject-matter of argumentation theory. Some similarities may be treated as a point of departure for further systematic exploration of the connection between pragmatic logic and argumentation theory. Figure 3 sketches future lines of inquiry by showing the relation between three research topics in pragmatic logic and in argumentation theory:

Moreover, some fundamental assumptions of pragmatic logic harmonize with methodological foundations (i.e. the subject-matter, goals and methods) of informal logic and pragma-dialectics. The main assumptions of this kind are: (1) the normative concern for reasoning and argumentation and (2) the claim that the power of the study of reasoning and argumentation manifests itself in improving critical thinking skills.

As it was shown above, the representatives of the LWS were fully aware of the pragmatic need of studying everyday reasoning. And the ideas of Ajdukiewicz were aimed to be systematically applied to teaching and educational processes. The title given by Ajdukiewicz to one of his papers (Ajdukiewicz 1965: What can school do to improve the logical culture of students?) clearly illustrates this approach to teaching logic. In order to stress the pragmatic dimension of this project, it should be mentioned that Ajdukiewicz together with other thinkers of the LWS applied the program in their work as academic teachers. In the Preface of his Introduction to Logic and to the Methodology of Deductive Sciences (1995) Tarski states:

I shall be very happy if this book contributes to the wider diffusion of logical knowledge. These favorable conditions can, of course, be easily overbalanced by other and more powerful factors. It is obvious that the future of logic as well as of all theoretical science, depends essentially upon normalizing the political and social relations of mankind, and thus upon a factor which is beyond the control of professional scholars. I have no illusions that the development of logical thought, in particular, will have a very essential effect upon the process of the normalization of human relationships; but I do believe that the wider diffusion of the knowledge of logic may contribute positively to the acceleration of this process. For, on the one hand, by making the meaning of concepts precise and uniform in its own field, and by stressing the necessity of such a precision and uniformization in any other domain, logic leads to the possibility of better understanding between those who have the will to do so. And, on the other hand, by perfecting and sharpening the tools of thought, it makes man more critical – and thus makes less likely their being misled by all the pseudo-reasonings to which they are in various parts of the world incessantly exposed today (Tarski 1995, p. xiii).

The program of pragmatic logic shows that the idea of the necessity of choosing formal and informal analyses of arguments is a false dilemma. For instead of competing with each other, formal logic and pragmatic logic are both legitimate instruments of research and teaching[viii].

NOTES

[i] LWS is characterized as an analytical school which was similar, to some extend, to the Vienna Circle (Woleński 1989; Woleński 2009) It should be noted, however, that Polish analytical philosophy is a broader enterprise than the LWS, since there were prominent analytic philosophers, such as Leon Chwistek or Roman Ingarden, who did not belong to the school (Jadacki 2009, p. 7). However, the analytic approach to language and methods of science constituted the key feature of the research carried on in the school.

[ii] Heinrich Scholz, who is claimed to be the first modern historian of logic (Woleński 1995, p. 363) called Warsaw one of the capitals of mathematical logic (Scholz 1930).

[iii] Deductivism is the view concerning the criteria which allow us to distinguish good and bad reasoning. The main thesis of deductivism states that good reasoning in logic is minimally a matter of deductively valid inference (Jacquette 2009, p. 189). The logical tradition of the LWS accepts deductivism, however it deals not only with reasoning, but also with broader ‘logical’ norms of defining, questioning or ordering. For the detailed characteristic of deductivism in formal and informal logic see Jacquette 2007, Jacquette 2009 and Marciszewski 2009.

[iv] The first President of the Association was Jan Łukasiewicz. The other members of the first Executive Board were Adolf Lindenbaum, Andrzej Mostowski, Bolesław Sobociński and Alfred Tarski. The constitution of the Association was adopted in 1938 (see The history of the Polish Society for Logic and Philosophy of Science).

[v] I do not claim, however, that the broad conception of logic, as accepted in the LWS, is unique. Examples of such a broad understanding of the term ‘logic’ may be found in the works of Antoine Arnauld and Pierre Nicole (Port Royal Logic), John Stuart Mill (The System of Logic. Ratiocinative and Inductive) and Charles Sanders Peirce (Collected Papers) (see the Appendix A in Johnson 2009, p. 39).

[vi] This is why classifying various types of inference was one of the crucial tasks for the representatives of the LWS (see Woleński 1989).

[vii] In the paper I do not discuss whether defeasible inference is a separate type of inference, as distinct from inductive inference. For the brief overview of the literature on this topic see e.g. Johnson 2009, p. 32.

[viii] I am grateful to Prof. Ralph H. Johnson for discussion which was inspiring for raising the main question of this paper. I thank Prof. Agnieszka Lekka-Kowalik for her helpful comments.

REFERENCES

Ajdukiewicz, K. (1957). Zarys Logiki (An Outline of Logic). Warsaw: PZWS – Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych.

Ajdukiewicz, K. (1965). Co może szkoła zrobić dla podniesienia kultury logicznej uczniów? (What school can do to improve the logical culture of students?). In K. Ajdukiewicz, Język i poznanie, t. II (Language and Cognition, vol. II) (pp.322-331), Warsaw: PWN – Polish Scientific Publishers.

Ajdukiewicz, K. (1974). Pragmatic Logic. (O. Wojtasiewicz, Trans.). Dordrecht/Boston/Warsaw: D. Reidel Publishing Company & PWN – Polish Scientific Publishers. (Original work published 1965). [English translation of Logika pragmatyczna].

Blair, J.A. (2009). Informal logic and logic. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 16 (29), 47-67.

Coniglione, F., Poli, R. & Woleński, J., (Eds.) (1993), Polish Scientific Philosophy. The Lvov-Warsaw School, Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Czeżowski, T. (2000). On logical culture. In T. Czeżowski, Knowledge, Science, and Values. A Program for Scientific Philosophy (pp. 68-75), Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi.

Eemeren, F.H. van (2009). Strategic manoeuvring between rhetorical effectiveness and dialectical reasonableness. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 16 (29), 69-91.

Eemeren, F.H. van & Grootendorst, R. (2004), A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jacquette, D. (2007). Deductivism and the informal fallacies. Argumentation, 21, 335-347.

Jacquette, D. (2009). Deductivism in formal and informal logic. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 16 (29), 189-216.

Jadacki, J. (2009). Polish Analytical Philosophy. Studies on Its Heritage, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Semper.

Johnson, R. H. (1996). The Rise of Informal Logic. Newport News: Vale Press.

Johnson, R. H. (2009). Some reflections on the Informal Logic Initiative, Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 16 (29), 17-46.

Johnson, R. H. & Blair, J. A. (1980). The recent development of informal logic. In J. A. Blair & R. H. Johnson (Eds.), Informal Logic, The First International Symposium (pp. 3-28), Inverness, CA: Edgepress.

Johnson, R. H. & Blair, J. A. (1987). The current state of Informal Logic. Informal Logic, 9, 147–151.

Kahane, H. (1971). Logic and Contemporary Rhetoric. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Kamiński, S. (1962). Systematyzacja typowych błędów logicznych (Classification of the typical logical fallacies), Roczniki Filozoficzne, 10, 5-39.

Kneale, W. & Kneale, M. (1962). The Development of Logic, Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Koszowy, M. (2004). Methodological ideas of the Lvov-Warsaw School as a possible foundation for a fallacy theory. In T. Suzuki, Y. Yano & T. Kato (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd Tokyo Conference on Argumentation (pp. 125-130), Tokyo: Japan Debate Association.

Koszowy, M. (2007). A methodological approach to argument evaluation. In F. H. van Eemeren, J. A. Blair, C. A. Willard & B. Garssen (Eds.), Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 803-807), Amsterdam: Sic Sat – International Center for the Study of Argumentation.

Lapointe, S., Woleński, J., Marion, M. & Miskiewicz, W. (Eds.) (2009). The Golden Age of Polish Philosophy. Kazimierz Twardowski’s Philosophical Legacy. Dordrecht/Heidelberg/London/New York: Springer.

Marciszewski, W. (1991). Foundations of the art of argument. Logic Group Bulletin, 1, Warsaw Scientific Society, 45-49.

Marciszewski, W. (2009). On the power and glory of deductivism. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 16 (29), 353-355.

McCall, S. (1967). Polish Logic, 1920-1939. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Przełęcki, M. (1971). O twórczości Janiny Kotarbińskiej (On Janina Kotarbińska’s Output). Przegląd Filozoficzny, 5 (72).

Scholz, H. (1930). Abriss der Geschichte der Logik. Berlin: Junker and Dünnhaupt.

Tarski, A. (1995). Introduction to Logic and to the Methodology of Deductive Sciences. New York: Dover Publications.

The history of the Polish Society for Logic and Philosophy of Science. Retrieved December 17, 2009, from http://www.logic.org.pl

Woleński, J. (1989). Logic and Philosophy in the Lvov–Warsaw School, Dordrecht/Boston/Lancaster: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Woleński J. (1995). Mathematical logic in Poland 1900-1939: people, circles, institutions, ideas, Modern Logic, 5, 363-405.

Woleński, J. (2009). Lvov-Warsaw School. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved June 20, 2010, from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/lvov-warsaw/

Woods, J., Johnson, R.H., Gabbay, D.M. & Ohlbach, H.-J. (2002). Logic and the Practical Turn. In D. M. Gabbay, R. H. Johnson, H.-J. Ohlbach & J. Woods (Eds.), Handbook of the Logic of Argument and Inference (pp. 1-39). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply