The Why, The What, And The How Of Asian Studies

No comments yet The articles in this section aim to promote the knowledge gathered in Asia Studies, as well as the relations between Asia and other regions of the world, and give impulses in order to advance research in this field. This also means pushing boundaries forward and push them beyond the often prejudiced views from within and without.

The articles in this section aim to promote the knowledge gathered in Asia Studies, as well as the relations between Asia and other regions of the world, and give impulses in order to advance research in this field. This also means pushing boundaries forward and push them beyond the often prejudiced views from within and without.

The Why, The What, And The How Of Asian Studies

Abstract

Management education frequently presents on a quasi-technical dimension. This is a matter of dealing with things but also the definition of what is relevant: for many in the field, only what can be technically managed is defined as relevant for business. Such strategy starts from presumptions that lack basic sociological knowledge. Even Max Weber, who centred a large part of his scientific work on showing the development of the iron cage of a bureaucratic system, underlined that such a system can actually only work if, at certain points, the basic rules are disregarded.

In the present contribution, the authors go beyond such a stance and claim that successful and sustainable strategies of management do not depend on occasional disrespect of the rules but on actively widening the framework to which those strategies refer. Centrally, it means that defining the focus of any management theory and management strategy culture has to play a central role. This is achieved not just by providing an adjunct position to culture but by highlighting its role as a central element discursively informing management issues in theory and practice.

Methodologically, this is guided by the concept of Sustainable Social Quality, which suggests a holistic approach by seeing the social as emerging from people productively developing the tension between processes and structures.

This approach will be empirically taken in this paper by looking at experiences in the field of teaching Chinese business.

Introduction

Looking historically at the development behind today’s thinking in the management sciences, we find a perspective that may in some ways come as surprise. Management had been the original core of the entire process, linking the different dimensions of a “good life”, as would be the focus of any socio-economic activity in Aristotelian thinking. In today’s language, these dimensions can be outlined as:

the administration and distribution of given resources;

the integrity and sustainability of distribution;

social appropriateness and justice;

the maintenance of borders.

Although production in the strict sense of the term does not appear on this list, the entire process is nevertheless focused on production. More importantly, the social is a matter of producing and reproducing everyday life. The socio-ecological relationship stands at the very centre of the process and we may say that the immediate and genuinely inherent link is guaranteeing sustainable growth and the effectiveness of management. In other words, the objective of management is inherently defined by the quality of growth, the latter being a matter of securing the “good life” in its own right. Importantly, the understanding of management and production was in the past fundamentally different to today’s understanding. Today’s Western take on management is characterized by (a) being separated from production, (b) being a tool, defined by its instrumental, technical character, (c) being subordinated to production, and – importantly – (d) being both disjoined from everyday life, defined by the reflexive understanding of an economy that has lost its political character, and being reduced to a means of producing exchange value for an anonymous market. Part of this new vision is the modernist double-step of the “as more as better” and “everything is possible”, suggesting not only the possibility but also the need for an exponential growth.

Paradoxically, management re-enters everyday life by changing the understanding of what life is about and suggesting that its goal is growth. This goes hand-in-hand with a fundamental and permanent push towards individualization.

It can now easily be claimed that this is a general and global development – and the legitimacy of such a statement should not be underestimated. We may even claim that management indeed equals management sui generis – and that it can be applied, and equally taught, in the same way in different countries and regions. With this in mind, we can then say that from this perspective it actually does not matter if we are talking about management in the West or in the East, in the North or in the South, or in any specific country. Moreover, we should be well aware of the power of prejudices and the mechanisms of self-fulfilling prophecy – mechanisms that are also relevant beyond influencing individuals’ behaviour and attitudes or the behaviour and attitudes of small groups. Nevertheless, it is equally true that any economy – and subsequently any economic thinking – is heavily influenced by the very traditional notion that still underlies the modern pattern of the global and world economy.

We may refer to the works of Karl Polanyi, who points out that capitalist market societies are historically an exception in human socio-economic relationships:

“Markets are not institutions functioning mainly within an economy, but without.” (Polanyi, 1944, p. 58)

This is another formulation of what Marx says when he points out that the economic and productive process is a social process in the twofold sense of (1) production by way of producing with others, and (2) producing social relationships. As general as markets may be, just as specific is their capitalist shape.

This brings us to the point that from any sound management strategy we have to return to a more fundamental issue of what economic development is about, namely, we need to focus on a process of relational appropriation. Relations are here seen as a matter of the relations of:

individuals with themselves;

between individuals in general;

between individuals as members of specific social entities (as in particular classes);

and, finally, between human beings and organic nature, or what we usually call the natural environment.

Even and perhaps especially today it is important to consider these general dimensions. Although global capitalism defines global rules, these are only an approximation and provide as such a very general framework within which concrete processes manifest themselves.

In addition, we have to consider that talking about global capitalism is problematic in its own terms. There are two principal reasons for this: first, the experience of socialist countries – be it the People’s Republic of China, the countries of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Совет экономической взаимопомощи, Sovet ekonomicheskoy vsaymopomoshchi, СЭВ, SEV), or today’s Cuba – clearly shows that they had been/are definitive part of a world system or global economy but that they are/were so without applying capitalist rule; second, though it is in some ways correct to speak simply of capitalism, it is in another respect not sufficient: capitalism is a complex interplay of accumulation regime and a mode of regulation (see Lipietz, 1986). And it is complex also in the sense of occurring in various formats, differentiated in a perspective that considers the different positions within the world system (cf. Hall and Soskice, 2001). If we take such an approach, we surely have to re-consider our understanding of management, asking what it actually is about. The following such reconsideration will look at four dimensions: (1) the need for management to reflect the specific mode of production towards which it is directed; (2) the inevitability of understanding socio-economic formations not least as part of complex cultures; (3) the existing patterns of teaching management as influenced by Western models; and (4) the outline of an alternative generalist approach on the basis of the Social Quality Approach.

Management as Part of a Specific Mode of Production

Both affirmation and critique of economic systems are in many cases very much characterized by the use of a broad brush to characterize the system. Of course, today, the commonly used terms and concepts are those of capitalism and neo-liberalism. Such a view is very much based on accepting the approach of modern economics that – following Marshall – deprived economic thinking of its political dimension. Perhaps this is also a crucial momentum that actually characterizes neo-liberalism itself. Although it is frequently described as a political philosophy, neo-liberalism is actually focused on the depoliticized “homo oeconomicus”, bereft of a political context and functioning completely independently from an adjunct moral system which would have been claimed as guiding and controlling; for instance, the Smithian version of the species of the homo oeconomicus. One surely has to criticize the classical liberalism for the separation of moral and economic thinking. However, neo-liberalism goes further by aiming to establish individualist morality itself as the highest moral and ethical instance: crucially, neo-liberalism paves the way for understanding the economy as completely “technicized”, i.e. reduced to a calculable relationship. Leaving more radical approaches aside, we know that for Weber, rational domination actually depends on the continued existence of charismatic and traditional modes of domination. Thus, we see that management is indeed very much caught in a contradiction. On the one hand, it is about the fundamental need to develop coping strategies to deal with real life; on the other hand, life itself is in this perspective reduced to a technical appendix of an economic process that is posited on quantifiable growth.

However, two problems go hand in hand with this. First, if such a “de-culturalized” approach can be viable at all, it can only be so for a limited period of time. This can be clearly seen by the fact that systems of capitalist production frequently enter phases of crisis. Such crises go beyond interruptions of the circle of production and exchange. They are more fundamental, concerned with the temporarily emerging question of meaning. These questions are of a general character and can be interpreted as cultural turning points in the mode of capitalist production. Second, we suggest that such cultural shifts are subsequently complemented by three further shifts, namely the techno-economic shift, which is presented by linking our thoughts to the Kondratieff idea of major cycles, the related shift of accumulation regimes, and the subsequent shifts of modes of regulation – all four can only be understood as one genuine entity.

Major cycles

It can easily be made out that there is a tight link between economic development and a change in the technological basis of production. However, it is useful to go a step further by characterizing some changes as inherently being techno-economic changes. In broad lines, we may refer to Kondratieff and his proposal that some bol’shie tsiklys, i.e. major cycles, are elementary forms of an overhaul of the entire productive basis. Importantly, “productive” refers to the complex understanding of production as outlined by Marx in his “Grundrisse” (1857), an entity made up of manufacturing, productive consumption, distribution, and exchange. We can go so far as to interpret technological change as an alteration of the metabolic relationship between human beings and the organic environment, that is, general social relationships and subsequent specific property relationships. Parts of these changes are actually for periods only relevant in some regions, without reaching others – even today some regions are barely reached by inventions that are commonly seen as “global appliances”. However, some of these inventions may be seen as global, inventions quickly “travelling” and being applied in different national contexts. Others are specifically re-invented, i.e. general technological possibilities are utilized to solve nationally and regionally specific challenges. In any case, the utilization and implementation is always merging with specific conditions, emerging as something that is specifically determined by what political science calls path dependency. In this light, we see that we can find major cycles always specified by specific “cultures”: the given mode of production and something that we name “property attitudes”. Briefly, property attitudes are societally dominant blueprints of responsibility that specify power and control:

“The important aspect is that this meant a subsequent division of power, splitting the process of appropriation into the two fundamentally different strands of generating and maintaining propriety on the one hand and the execution of control on the other hand.

Important is to note that the momentum of control has itself again two dimensions, the one of it being a matter of contestable legitimacy, the other a matter of actual capabilities.”

(Herrmann and Dorrity, 2009, p. 12 f.)

As abstract as it may sound, it is actually a matter that is of immediate relevance to our present discussion. For instance, we can think of the typical definitions of enterprises and also the degree of technical (dis-) integrity of enterprises, i.e. degrees of specialization and outsourcing. Of immediate interest furthermore are the structures of supervision and the focus on “competitive closure” – the latter may be exemplified by juxtaposing the strategies of Mircosoft and Linux in developing open source software.

In short, we may speak of national patterns of implementing Kondratieff cycles in a very specific way – and subsequently, we propose to speak of major national cycles of management. These parallel Kondratieff cycles and can be seen as specific translations between major technological changes and national traditions of management and work organization.

Accumulation regimes

To understand this thoroughly in its entirety, we have to look at the wider context, namely modes of production. The first point of reference can be seen in the definition of the accumulation regime as given, for instance, by Lipietz, who contends that:

“[a] system of accumulation describes the stabilization over a long period of the allocation of the net product between consumption and accumulation; it implies some correspondence between the transformation of both the conditions of production and the conditions of the reproduction of the wage earners. It also implies some forms of linkage between capitalism and other modes of production. [. . .] A system of accumulation exists because its schema of reproduction is coherent . . .” (Lipietz, 1986, p. 19)

The core challenge is to analyse the aforementioned process of “translation” into the economic process. However, going beyond the focus that is traditionally taken by the regulationist approach, we should adopt a wider understanding of the political-economic process as point of reference. This is, at its very core, defined by the fact that: “production is appropriation of nature on the part of an individual within and by means of a definite form of society.” (Marx, 1857, passim)

This has to be considered against the background that:

“[t]he human being is in the most literal sense a political animal not merely a gregarious animal, but an animal which can individuate itself only in the midst of society. Production by an isolated individual outside society . . . is as much of an absurdity as is the development of language without individuals living together and talking to each other.” (ibid.)

This allows us to review the so-called factor theory put forward by mainstream economics in a socio-cultural light. The factors of production are then importantly characterized from two additional perspectives (additional to the techn(olog)ical side): the first relates to the cultural element that defines the individual factors and their relative meaning, the second to the way in which the different factors are related to each other. This is relevant in two regards, namely production and consumption.

Again this may sound abstract, but it is again a matter of very concrete interest to the management sciences. The economies of scale and their concrete “use” in fostering the productive process are also important at this stage. Similarly important are the degree and the way of financing: depending on a variety of factors, from the natural environment and the size and structure of the enterprise to the degree of diversification, we see that a specific pattern emerges that defines the relationship between the different elements of the accumulation regime. One may say that there is no need for cars in places without distance.

Mode of regulation – political systems and property relationships

We are thus concerned with a complex field in which, on the one hand, the “economic sphere” is becoming very much a matter of immediate political culture of the mode of production, and in which, on the other hand, regulation itself is a core moment of the economic process. Usually, the regulatory tradition is first and foremost oriented towards analysing the institutional and non-institutional aspects of the overall political system (government and governance). However, it is useful to also include the management level. The reason for this is twofold: first, it is distinct layer in the overall governance structure. But more important for the present argument is the second reason: the fact that we are now dealing with another layer of translation. Both general societal norms and the power and property structures are core moments and part of the commonality of global capitalism, and at the same time it’s partial disintegration – systemic collapse would be (and frequently is) the consequence in those cases in which political and management activities are limited to the application of formal rules.

Though one may surely reflect on a hierarchy between these different dimensions this is, for the present debate, not of interest. Instead, it is useful to understand these four dimensions of social quality, elaborated further below as elementary forms of a complex entity that is a political-economic specification of the social – this will be presented at a later stage as part of the Social Quality Approach.

The Cultural Dimension of Socio-Economic Formations

Huibin and Dirlik highlight the need to be conscientious when it comes to contemplating the character of globalization as:

“globalization of capitalism is accompanied by its disintegration into a variety of social, political, and cultural formations. It is capitalism . . . that provides the commonality that makes it possible to speak of globalization or global capitalism. It is the contradictions created by difference that make many wonder if there is such a thing as globalization and that present obstacles even to global organizations such as the WTO.” (Huibin and Dirlik, 2008, p. 173)

The problematique we are facing is also well expressed in the following sentence, taken from a text that claims to be highly critical of globalization and in which Irogbe contends:

“After all, ‘pure’ cultures rooted in one particular geography are as mythical a conception just as pure races undiluted by miscegenation. Therefore, throughout history, cultures, along with people, have constantly diffused and re-fused in new settings and forms. Despite the diffusion of cultures, there are still discernible cultural differences among peoples of different nations. A country’s cultural heritage reflects its history, faith, and value system. The poorer the country, the more the people cling to their cultural heritage. In less-wealthy nations, cultural treasures are part of the citizens’ identity. When people’s dignity is shattered we have to help them to restore their faith and values. We can assist them in achieving stability and security by honoring their traditions and identity. And that is consistent with internationalization and multiculturalism rather than the pursuit of globalization or homogenization.” (Irogbe, 2005, p. 51)

Cum grano salis, this reflects the same pattern of argument as is criticized by Huibin and Dirlik (2008) in their examination of “post-societies”. As much they see “post-societies” as being defined by their residual character, with no character that is genuinely their own (Huibin and Dirlik, 2008, p. 146), we see in the approach pursued by Irogbe (2005) the permanence of reference to the hegemonic “rich countries”, which actually defines the standards for assessing “otherness” – though he claims this has genuine status in its own right. In other words, even if it is not about striving to be like the West, the “negativity” is core of the consideration and a positive juxtaposition is not presented – the old question of adjustment and delinking (on this general debate, see for example Mahjoub, 1990).

The fundamental challenge is to recognize the very limited approaches of contemporary debates that are determined by uncritically accepting spatial (“Western”) and temporal (“presence”) hegemonies, i.e. which adopt the presumption of the present West being the standard against which the rest of the world, “the other”, is assessed for all eternity – and indeed it carries with it some teleological character. Even if the time and space change, it does not affect the superiority of the standard. Of course, this evokes paradoxes, as for instance in the view that the “strength” of newly emerging BRIC countries is very much not related to the performance of these countries but instead to the mal-performance of the “old hegemony” and the high degree of adaptability of the BRIC countries to the ground patterns of “the West”. It can be concluded that even in critical thinking globalization is very much also considered as globalizational socio-cultural pressure towards conflation. This is, of course, a relevant statement; however, it neglects the fact that a crucial part of this process is that “advanced” accumulation regimes always depend to some extent on less advanced modes of accumulation – this was pointed out earlier when the definition of an accumulation regime was presented by quoting the work of Lipietz (1986). To be more precise, globalization, from the perspective of world systems theory, is exactly related to the fact that different modes of production are insolubly linked due to and on the grounds of the differences between them. This goes hand in hand with a specific pattern in the level of the enterprise. Max Weber’s typology of different modes of authority/domination is well known, including the charismatic, traditional, and legal/rational. If we accept this as rough heuristic guideline that can also be used for analysing management structures, we can propose that these modes of authority/domination can actually be seen as somewhat parallel to modes of production. Thus, we arrive at a multi-layered process-orientation of management that comprises four layers:

the developmental stage of the mode of production;

the developmental stage of the mode of authority/domination;

the developmental stage of personalities or “national characters”;

the adaptability of management strategies to different conditions and the ability to adequately respond to the challenges on the different levels in a “consistent” and holistic approach.

From this it follows that management is the skill of dealing with differences in time, space, scope, and depth. Translated further into the language of international management education, we are here confronted with the challenge of responding to the interpenetration of different socio-economic systems by developing new research, approaches, and teaching material.

Understanding of Management in Teaching Asian Studies

The end of World War II saw the U.S. emerge as the most powerful society in the world. Much followed from that, not least the attempt to both export U.S. good practices and imitate them. This was particularly marked in the management sciences. Business education had emerged in the U.S.A. in response to the economic crisis of 1929, which was widely blamed inter alia on the lack of the existence of a professional management cadre independent from ownership, whether individual or family. It was Harvard University that responded to this insight by developing the Harvard Business School and the case approach to management education. This became the touchstone for management education worldwide.

The view that economic recovery would be well served by the development of management as a profession with its own body of knowledge was reinforced by additional political concerns. The need to develop civil society as dense societies consisting of a range of standalone robust professional groupings independent of the state was seen as critical to blocking the re-emergence of totalitarian regimes, whether of the right or of the left. The development of management education as distinct from economic or social science education post-1945 stems from these considerations. All this linked back to the U.S.’s attempt to gain global dominance . There then followed a massive development of American-style business education with the exception of the socialist world. So what was it that was being emulated with such speed and enthusiasm?

American management science rests on two cultural dimensions, namely a belief in the application of reason and a commitment to the individual’s right to happiness. Belief in the appropriateness of reason, seen as a cultural phenomenon accessible to all honed though debate, links back to the 18th century French tradition and ultimately to the ancient Greeks. In addition, the pioneering experience of the early settlers only reinforced the significance attached to the pursuit of happiness, the right to happiness seen as having been achieved through a constant focus on problem solving and achieving practical outcomes.

And with pursuit of happiness came the belief that anything was possible, that wealth could grow unrestrainedly for the betterment of the individual worldwide. We are speaking here of an ideology that has continued to drive the development of management education in the West.

Not all the countries of Europe responded post-1945 to the belief that the development of management education as an academic subject in management schools was the way to ensure economic reconstruction. Germany was the only exception and remained outside this trend .

The years between 1980 and 2000 saw the creation of the vast majority of business schools worldwide. During that period, for example, the U.K. alone saw business schools created in Manchester, London, Bradford, Warwick; in Scandinavia in Copenhagen; in the Netherlands in Rotterdam; in France, INSEAD and EM in Lyon; in Italy in Bocconi; in Spain, ESADE and IESE; and, finally, in Ireland, Smurfit and Limerick. Ireland now has the highest per capita percentage of business schools in the world.

These developments did not occur without tensions, between, for example, the certainty of U.S.-derived models and realities on the ground. But behind this was the wider buy-in to the assumption of convergence with the U.S. “models of excellence” at both an organizational and personal level worldwide. If excellent companies were now believed that they needed to mimic American models in order to grow academics in the management sciences needed to be imbued with such understanding . It followed that academics in the management area were also going to imitate the behaviour of their American peers. Significant career opportunities became available outside the U.S. for American academics in the management area.

For non-U.S. academics, to be excellent in the area demanded that one had to be trained in or have spent time as a visiting professor in the United States, returning as an expert in the field of American management theory, teaching American material. Career advancement, both in and outside of the U.S., now required citations in U.S.-based journals whose boards were U.S. dominated.

Against this background, how has China addressed the issues of management education? China has seen in the last 20 years a significant development of senior university-based business schools, including the emergence of internationally recognized elite schools of world-class standard, such as Fudan University School of Management and Shanghai. Jiao Tong University Such schools play an increasingly prominent role in Chinese society and are sought after not least by the central government authorities, who constantly draw on leading academics in the management areas, expecting input into the development of the next five-year plan, each plan setting the trajectory for China over that time period.

As these schools have developed, they have gradually increased their international faculties, moving from only offering visiting or short-term appointments to the development of internationally recruited China-based faculties. This development echoes a central theme in China, that of “Catching Up”. As with development of Special Economic Zones, a major driver of international academic recruitment in China has been the acquisition of know how to be then mainstreamed into Chinese business practice. There has been significant know how leveraging based on the return of academics drawn from the descendants of the Chinese expat community.

Nor are Chinese academics now tied to seeking publishing outcomes in the West. There has been a huge increase in the number and reputation of Chinese-based academic periodicals. The index to the list of main periodical in the humanities and social sciences as of 2012 showed 500 citations. So far, this development appears similar to the developments that took place elsewhere after 1945. But at a curriculum level, there are differences not just organizationally but in terms of the focus and range of subjects covered. In sharp contrast to much management education in the West, Chinese schools give significant weight to Chinese philosophy and public sector macro-economic management. The interface between academic activities and the state is also different. Not only are academic appointments at all levels overseen by the state but research interests can also be constrained.

Then there are the administrative schools, which have clearly defined areas of excellence, to which only members of the party are invited as students. This means that management education in the party is dominated by the approach found in the administrative schools. The schools of administration and Party schools have featured highly in management education over the last decades. With a primary focus on state officials at all levels, they have increased in both number and scope and now include managers in state enterprises. The curriculum offered is very distinct, centred around the three themes of contemporary society, “historical significance, scientific context and the road to socialism with Chinese characteristics.” (e.g. F N Pieke: The Good Communist Cambridge University Press 2009) All curricula in these schools contain these three elements. The schools are important for management education in China as they offer training not only to public sector officials but also to managers in state-owned enterprises. This means that many of the senior managers in the largest companies in the state have been educated in these schools rather than as in the West in executive programmes in main stream universities . Administrative schools have recently begun to contribute to academic journals in China and provide significant intellectual input into Chinese state policy.

The development of Chinese-based management academics as world leaders is likely to have several outcomes. While U.S. management theory is tied to Socratic dialogue, a link that is largely historic and focused on shareholder value, Chinese management theory is likely to emphasize group harmony and long-term cultural continuity. Analysis suggests a move from a Western-based convergence theory for management theorists to a theory of embededness. For management educators in the West, there are significant implications if we are aiming to prepare our students to be effective in an increasingly Asian-centric world. If that is the goal, we will need to change business curricula to encompass philosophy, both Western and Eastern, and particularly the logic of discourse and mutual history, without minimizing previous difficulties. We will need to refocus on relationship skills, including limao, while teaching the distinction between normative politeness and strategic politeness as a must. We urgently need to think though the implications for learners presented with conflicting models of excellence in joint degrees. We also need to change the focus of our work to include issues relevant to domestic Chinese issues, though that will only occur if we achieve both research access and credibility and learn to interpret the information supplied. And we have to acknowledge language skills as central, minimally requiring mandatory situational language acquisition. Finally, we have to examine minimally propositions focused on parity of esteem for Chinese and Western business models.

As Rolf Cremer recently argued, business schools need to support this shift in mind-set by promoting a vision of business success as a transformation process based on mutual trust between the different stakeholders involved. Rather than relying on a leadership ideal that fosters quick growth by means of a finance-oriented approach, China may find itself in a unique position where it is confronted with the possibility of transforming leadership in ways that can truly enhance the ability of people to regulate their behaviour and decisions towards a more sustainable economy.

The Social Quality Approach as Alternative Generalist Approach

Looking back at the beginning of this contribution and interpreting in that light the development, it is clear that the mainstream teaching of management is limited in two ways: (1) it focuses on one side of the entire spectrum of the socio-economic process, and (2) it narrows the economic dimension itself to a “technicality”, suggesting that it can be treated in a schematic way. Thus, we may say that in this version of management (education), human beings are reduced to a narrowed version of the homo oeconomicus and that, furthermore, this limited human being is reduced to a functioning instrument, not only bereft of a political context but also bereft of its character as agent.

Certainly, thus legitimizing a specifically bounded rationality finds some justification – but actually it is the justification of a crisis economy that is limited in a self-reflexive orientation. Even to the extent to which a “human dimension” is added, we find that this is only by way of referring to labour as productive factor (“human capital” as it is usually and misleadingly called). Without delving into this debate, it is from various angles clear that this is insufficient. The theory of productive factors is frequently criticized for actually fading out the fact that it is not labour but labour power that is entering the productive process. And it is equally clear that we are dealing with complex historical processes that require attention in their multiplicity in order to clearly understand the complex dimension of actor-defined processes within certain spacetimes (on spacetime, see Herrmann, 2013; Jourdon and Herrmann, forthcoming).

In this case, the orientation on Social Quality may offer a valid contribution as it actually questions the social itself by looking for a definition of it, asking for the meaning of the noun. In the work of the European Foundation of Social Quality, it is then understood as:

“an outcome of the interaction between people (constituted as actors) and their constructed and natural environment. Its subject matter refers to people’s interrelated productive and reproductive relationships. In other words, the constitutive interdependency between processes of self-realisation and processes governing the formation of collective identities is a condition for the social and its progress or decline.” (Van der Maesen and Walker, 2012, p. 260)

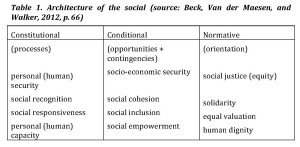

The architecture is analytically composed of three sets of factors, which are presented in the following table (Table 1).

This outlines at least some framework for management (studies) in fields of distinct cultural character – and, actually, its application should not be restricted to large-scale differences, i.e. differences such as those between the U.S. of Northern America, Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Instead, it is equally relevant as a point of reference for intra-systemic analysis. The crucially important point is that management is rejoined with the wider array of production and furthermore that production is rejoined with the (re-)production of everyday life. As such, management is seen not as the provision of a set of guidelines but as a structured field for the evaluation of processes. This reflects another definition of the social, namely, as a process of relational appropriation, as briefly mentioned above. One of the crucially important aspects is that management is, from this perspective, always process management: a matter that is in its own terms in a fourfold process linked to interculturality. First, it needs to be compatible with the existing cultural paradigms of action; second, it needs to be itself geared toward practice, thus going far beyond a sequence of individual acts; third, this way it allows to connect also to different contexts as it is concerned with posing the why-questions instead of assuming the quid-pro-quo as given; fourth, it allows also for dealing with difference in a constructive way.

Adopting such a framework – here only presented in very broad terms – aims at understanding management (education) as matter of social enablement. It can be transposed into a strategy of transformative learning, as expressed by Babacan and Babacan:

“Critical reflection and dialogue are central to the process of transformative learning. Mezirow (1990, 1991, 2000) argues that in transformative learning, the most significant learning takes place in the communicative domain. This process involves identifying problematic ideas, values, and beliefs, by critically examining the assumptions upon which they are based, testing their justification through dialogue and the making of decisions upon the ensuing dialogue (Nazzari, McAdams, and Roy, 2005; Taylor, 1998, p. 43).” (Babacan and Babacan, 2013, p. 205, with reference to: Mezirow, 1990; Mezirow, 1991; Mezirow, 2000; Nazzari, McAdams, and Roy, 2005; Taylor, 1998)

Of course, this is not just a fancy theoretical notion, a kind of utopian claim. Such a strategy of transformative learning is in the Chinese understanding a very concrete challenge that has transformed training processes. Managers, fully trained and qualified, are still requested to return every four years for some kind of retraining. One could also say that this way of transformative training emerges as reflexive practice.

REFERENCES

Altvater, E., 2009. Interviewed by R. Zeilik, 2009. Vermessung der Utopie. Ein Gespräch über Mythen des Kapitalismus und die kommende Gesellschaft [Survey of utopia. A discussion of the myths of capitalism and future society]. München: Blumenbar.

Babacan, A. and Babacan, H., 2013. The transformative potential of an internationalised human rights law curriculum. Journal of Transformative Education, 10(4), pp. 199–218.

Beck, W., van der Maesen, L. J. G., and Walker, A., 2012. Theoretical foundations. In: L. J. G. van der Maesen and A. Walker, eds. Social quality: from theory to indicators. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 44–69.

Hall, P. A., and Soskice, D., eds., 2001. Varieties of capitalism. The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Herrmann, P., 2013. Human rights – Good Will Hunting vs. Taking Positions. In: S. Kalaycioglu and P. Herrmann, eds. Social policy and religion. New York: Nova. Ch. 2.

Herrmann, P. and Dorrity, C., 2009. Critic of pure individualism. In: C. Dorrity and P. Herrmann, eds. Social professional activity: the search for a minimum common denominator in difference. New York: Nova. pp. 1–27.

Huibin, L. and Dirlik, A., 2008. Dialogue on post-capitalism – interview with Arif Dirlik. boundary 2, 35(3), pp. 133–187.

Irogbe, K., 2005. Globalization and the development of underdevelopment of the third world. Journal of Third World Studies, 22(1), pp. 41–68.

Jourdon, P. and Herrmann, P., forthcoming. Risk governance and ethics.

Lipietz, A., 1986. New tendencies in the international division of labor: regimes of accumulation and modes of regulation. In: A. J. Scott and M. Storpor, eds. Production, work, territory: the geographical anatomy of industrial capitalism. Boston, London and Sydney: Allen and Unwin. pp. 16–40.

Mahjoub, A., ed., 1990: Adjustment or delinking?: the African experience. Tokyo: United Nations University Press.

Marx, K., 1986 (1857): Introduction (to an outline of the critique of political economy). From the Philosophical-Economic Manuscripts. In: K. Marx and F. Engels. Collected works, volume 28. London: Lawrence & Wishart. pp. 17–48.

Mezirow, J., 1990. How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. In: J. Mezirow, ed. Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: a guide to transformative and emancipator learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. pp. 1–20.

Mezirow, J., 1991. Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J., 2000. Learning to think like an adult: core concepts of transformation theory. In J. Mezirow ed. Learning as transformation: critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. pp. 125–148.

Nazzari, V. , McAdams, P., and Roy, D., 2005. Using transformative learning as a model for human rights education: a case study of the Canadian human rights foundation’s international human rights program. Intercultural Education, 16, pp. 171–186.

Polanyi, K., 1944. The great transformation: the political and economic origins of our time. Boston: Beacon Press.

Taylor, E. W., 1998. The theory and practice of transformative learning: a critical review. Ohio vocational education, Ohio State University.

Van der Maesen, L. J. G. and Walker, A., 2012. Social quality and sustainability. In: L. J. G. van der Maesen, and A. Walker, eds. Social quality: from theory to indicators. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 250–274.

Published in: Fan Hong, Peter Herrmann & Daniele Massaccesi (Eds.) – Constructing the ‘Other’ – Studies on Asian Issues – ISBN 978 3 86741 892 8 – Bremen, 2014

About the authors:

Professor Peter Herrmann received his PhD at Bremen, Germany. He is senior academic at the European Observatory for Social Quality which is a new research unit at EURISPES in Rome, Italy. He is also adjunct professor at the University of Eastern Finland (UEF). His main interest shifted over the last years towards developing the Social Quality Approach further, looking in particular into the meaning of economic questions and questions of law. He linked this with questions on the development of state analysis and the question of social services. On both topics he published widely.

Professor Emeritus Deirdre Hunt is a graduate of the London School of Economics (BSC Hons Sociology) and obtained her PhD in Education and Training of Family Heirs at Bradford Business School. Previously Associate Professor of Management in University College Cork, she has been a visiting Professor at the Universities of Leiden, Texas, Kobe and EM Lyon and currently directs an annual case seminar at the University of Klagenfurt. She is a founding member of the ESIAM based European network for Asian Management research.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply