Chapter 5: Irish FDI In China ~ Evidence, Potential And Policy ~ Irish Investment In China. Setting New Patterns

Introduction

Introduction

Having set out the locational advantages and disadvantages which China possesses, this chapter will explore the non-applicability of Irish FDI in China to Barry et al‘s (2003) model for developed economies, and will attempt to explain why there is such a divergence. It can be argued that there is a view which equates outward FDI with the re-location of jobs abroad. In order to address this perception, the effects of outward FDI on the home economy will be explored. Acknowledging that our sub-hypothesis holds and that the investment climate in China is different from that faced by Irish investors in developed economies, we will explore our prescriptive research question, namely the role which exists for government in supporting potential investors who wish to enter the Chinese market.

Barry’s Model

Barry et al’s (2003) model states that Irish outward FDI is disproportionately horizontal in nature and oriented towards non-traded sectors. This model is based on an analysis of Irish FDI in the traditional destinations for Irish FDI, namely the US and UK, both of which are developed economies. This research analysed Irish FDI in China, a developing economy. While accepting the limited nature of this research, it was found that 82% of FDI is in the traded sector and only 18% in the non-traded sector. It can be said, therefore, that this finding is at variance with the model for developed economies, as set out by Barry et al (2003). Secondly, in relation to the horizontal or vertical nature of Irish FDI in China, this research identified 55% as being of a horizontal nature and 45% as being vertical. Barry et al’s model states that Irish traditional FDI in developed economies is “disproportionately horizontal in nature’. 55% could not be described as ‘disproportionately horizontal’. Accordingly, this finding also deviates from Barry et al’s model. Accepting the difficulty of measuring the true level of horizontal versus vertical FDI, as highlighted in the literature review, the figure of 55% is below the level of 70% which Moosa (2002) contends may be the general order of horizontal FDI. This points to the level of horizontal Irish FDI in China being somewhat lower than the norm and not as strong as would have been anticipated had it been in accordance with Barry et al’s model.

We can say that this research indicates that the current wave of Irish FDI in China is predominately in the traded sector and marginally horizontal in nature.

Accepting that the sample size for this research is limited, it is nevertheless an accurate reflection of current investment patterns by Irish MNEs in China.

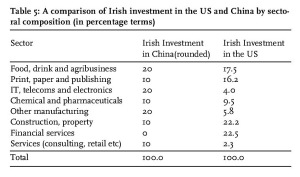

Table 5: A comparison of Irish investment in the US and China by sectoral composition (in percentage terms)

Irish FDI in China and Barry’s Model

It is also interesting to examine whether the limited Irish investment in China diverges or conforms to the sectoral composition identified by Barry et al (2003) for developed economies. Using the categorisation of Irish investment in the US put forward by Barry et al (see table 3 in previous chapter), the following comparisons can be made (Table 5):

The percentage for food, print and chemicals is not greatly different between both categories. IT, telecoms and electronics are considerably more important in the case of China. Significant deviations can be identified in ‘other manufacturing’, financial services and construction to a lesser degree. Notably, the Irish financial service sector is absent from China. Again acknowledging the small sample size of this research, current Irish investment trends into China show a divergence from patterns identified for investment in the US.

Why then does Irish FDI deviate from Barry et al’s model and also diverge in sectoral composition from that identified in traditional destinations for Irish outward FDI? There may be several possible explanations.

Recalling that firms invest abroad because they possess ownership and internalisation advantages, Barry et al (2003) suggest that R&D and superior product differentiation through advertising are generally found to be the most important firm-specific assets associated with multinationality; but Irish MNEs do not appear to follow the standard pattern associated with multinationality. Instead, they propose that the predominant proprietary assets which Irish firms possess are in the fields of management and expertise, mainly in non-traded sectors. However, this research found that the composition of Irish MNEs investing in China is largely in the traded sector. It is possible, therefore, that because the expertise of Irish MNEs largely lies in the non-traded sector, this is inhibiting current levels of FDI in China, given the largely manufacturing and traded nature of the Chinese economy at this point in time.

Secondly, the structure of the Irish economy can be broadly defined as highvalue output with little high-volume low-value manufacturing. (This results from the relatively high cost structure of the economy, as compared with developing economies). While Barry et al point out that the Investment Development Path hypothesis is silent on the distinction between vertical and horizontal FDI, they claim that as production costs rise there is an incentive for domestic firms to engage in vertical FDI, moving labour-intensive components to countries with a locational advantage in low-cost labour. This opportunity was identified by a very limited number of Irish MNEs. While China’s low wage cost environment may facilitate some Irish investment, market opportunity remains the primary investment objective. Read more

Chapter 6: Conclusions & Bibliography ~ Irish Investment In China. Setting New Patterns

Introduction

Introduction

Based on research undertaken on Irish outward FDI into the US and UK, both of which are developed economies, Barry et al conclude that Irish FDI is disproportionately horizontal and oriented towards non-internationally traded sectors. As China is now the largest global recipient of inward FDI, and is a developing economy, research was undertaken among all Irish MNEs which have invested in China to ascertain if current Irish FDI into China conforms to the model identified in the case of Irish FDI into the US and UK. Accepting that the level of Irish FDI in China is at a relatively low level, the value in considering this hypothesis is that Irish FDI in China will presumably increase, given China’s pre-eminent role in inward FDI.

While there are several investment theories, Dunning’s eclectic paradigm was chosen as the optimal framework within which to conduct this research, as it facilitates simultaneous analysis of the advantages enjoyed by both the MNE and the host economy.

Desk-based research and semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the nature of Irish FDI in China. The decision to use semi-structured interviews to obtain data on the perceptions of executives can be considered appropriate, as the executives provided rich data on the rationale underlying the investment decision and the locational advantages and disadvantages which China poses.

Executives of non-Irish MNEs which have invested in China were interviewed in addition. The inclusion of non-Irish MNEs provided an opportunity to corroborate the views of executives of Irish MNEs and provided a broader pool of expertise from which to gather perceptions on the locational advantages and disadvantages which China poses for investors. Executives from Irish MNEs which have invested in Eastern Europe were interviewed separately to gain an understanding of why the level of Irish FDI into China is relatively low.

Main Findings

Barry et al (2003) analysed the nature of Irish outward FDI and observed an increasing level of Irish outward FDI. The main destination for this FDI is developed economies, particularly the US and the UK. It is suggested that Barry et al made a significant contribution to the research into Irish outward FDI by their identification of Irish outward FDI as being disproportionately horizontal and oriented towards non-internationally traded sectors. This research builds on their model and extends the knowledge of Irish outward FDI by examining the nature and scope of Irish FDI into China, a developing economy. The value in studying FDI in China lies primarily in its status as the principal recipient of inward FDI globally. Since the introduction of the ‘opening-up’ policy in 1979, economic reforms in China have created an increasingly favourable climate for inward FDI. However, considerable challenges still remain with inadequate legal protection and challenges to intellectual property rights.

But Beijing’s desire to expand the service and private sectors, combined with its willingness to allow foreign firms to compete nearly across the board, means that the China market is now becoming a real opportunity just as the purchasing power of Chinese consumers is beginning to increase. And China is likely to remain the world’s fastest growing major economy for the coming decade and beyond …Understanding how to do well in China and with Chinese resources will become a critical component in a global competitive strategy. (Lieberthal and Lieberthal, 2004: 11)

In order to deepen our understanding of the nature of Irish FDI and specifically the nature of Irish FDI in the largest global recipient of inward FDI, this research has examined the hypothesis that the nature of Irish outward FDI, as identified by Barry et al, varies in the case of China. This research has contributed to our understanding of Ireland’s investment development path by introducing a study of Irish outward FDI in a developing economy for the first time. Read more

The Why, The What, And The How Of Asian Studies

The articles in this section aim to promote the knowledge gathered in Asia Studies, as well as the relations between Asia and other regions of the world, and give impulses in order to advance research in this field. This also means pushing boundaries forward and push them beyond the often prejudiced views from within and without.

The articles in this section aim to promote the knowledge gathered in Asia Studies, as well as the relations between Asia and other regions of the world, and give impulses in order to advance research in this field. This also means pushing boundaries forward and push them beyond the often prejudiced views from within and without.

The Why, The What, And The How Of Asian Studies

Abstract

Management education frequently presents on a quasi-technical dimension. This is a matter of dealing with things but also the definition of what is relevant: for many in the field, only what can be technically managed is defined as relevant for business. Such strategy starts from presumptions that lack basic sociological knowledge. Even Max Weber, who centred a large part of his scientific work on showing the development of the iron cage of a bureaucratic system, underlined that such a system can actually only work if, at certain points, the basic rules are disregarded.

In the present contribution, the authors go beyond such a stance and claim that successful and sustainable strategies of management do not depend on occasional disrespect of the rules but on actively widening the framework to which those strategies refer. Centrally, it means that defining the focus of any management theory and management strategy culture has to play a central role. This is achieved not just by providing an adjunct position to culture but by highlighting its role as a central element discursively informing management issues in theory and practice.

Methodologically, this is guided by the concept of Sustainable Social Quality, which suggests a holistic approach by seeing the social as emerging from people productively developing the tension between processes and structures.

This approach will be empirically taken in this paper by looking at experiences in the field of teaching Chinese business. Read more