The Art Of Cooking – Bamia With Rice

Bamia (Okra Stew) is an important dish in Iraqi cuisine, it is a simple dish and yet a delicious dish that can be made with or without meat.

Bamia (Okra Stew) is an important dish in Iraqi cuisine, it is a simple dish and yet a delicious dish that can be made with or without meat.

Bamia (Okra) itself is not the most popular vegetable out there, but once you can look past its slimy structure it is actually really tasty.

Bamia has a rich sweet and earthy flavor which is well contrasted with the acidity of tomato.

Bamia as well as other stew are great to eat with rice – in this recipe, I will teach you how to make your rice a little bit more exciting!

Ingredients:

Okra 500 gram (you can find Okra at your local Mediterranean shop, It should be fine for both fresh or frozen)

Lamb meat 500 gram (it could be made with either meat or chicken)

Can of peeled tomatoes

Tomato paste

2 onions

Garlic

White rice (I myself prefer Basmati rice, but any white rice will do)

Can of chickpeas

Salt & Pepper

Dried bay Leaf

Cumin

Cooking oil

Bamia (Okra Stew):

Start with heating up a layer of oil in a big pot.

Season the meat with salt and pepper and add it to the hot oil.

Make sure all sides of the meat get cooked do not worry about the pot getting too sticky.

Next add some cumin, diced garlic, and diced onion.

When the onion turns translucent, add some tomato paste together with the can of peeled tomatoes.

Use the liquid to clean the bottom of the pan and mix the flavor into the sauce.

Rinse the okra and add it to the pan, add enough water to cover all ingredients, and let it simmer for an hour or more (the more the better).

Make sure it does not get too dry while simmering on the stove.

When the meat is soft enough (prick the meat with a fork to check if it is ready).

Taste for salt before serving.

Rice:

Let’s try to make exciting rice, for the extra pleasure of eating the Bamia.

First of all, measure the rice into a cup and level the top, and then rinse it in cold water – make sure to remove all the dirt – prepare a measured amount of water equal to 1 and a half cup that you used for the rice.

In a deep frying pan add a layer of cooking oil, when the oil is hot add a dried bay leaf and chopped onions, and some cumin.

When the onion turns translucent, add some tomato paste and be sure to stir frequently.

As the mixture starts to dry up add the water you have already measured and mixed all together.

After mixing the water with the paste add the rice and chickpeas (make sure to rinse the chickpeas in cold water) and add a pinch of salt.

Now put the lid on the frying pan, and make sure the water simmers – once the water starts boiling turn the heat down.

When the water is no longer visible in the pot, the rice is ready.

It is nice to serve the Bamia and the rice, with some fresh cucumber, tomato, and with some chopped parsley leaves on top.

Please try to make Bamia, even if you never had Okra before – it is after all a unique vegetable.

So finally, I hope you like it as much as I do.

Erin Ben-Moche – Photographer Zion Ozeri Showcases Jewish Diversity in Virtual Haggadah & Pictures Tell: A Passover Haggadah

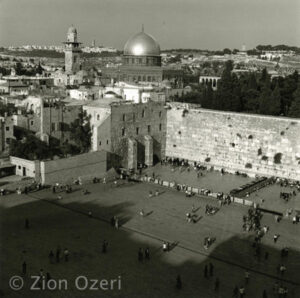

Renowned Jewish photographer Zion Ozeri is no stranger to creating meaningful Haggadot. His award-winning photographs, which capture the world around him, have appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, The Jerusalem Report, Moment and The Economist, to name a few publications.

Renowned Jewish photographer Zion Ozeri is no stranger to creating meaningful Haggadot. His award-winning photographs, which capture the world around him, have appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, The Jerusalem Report, Moment and The Economist, to name a few publications.

After reviewing his pieces, Ozeri decided to create a virtual interactive Haggadah that highlights the diversity of Jews, just in time for a second pandemic Passover.

Ozeri, along with Sara Wolkenfeld and Josh Feinberg, curated “Pictures Tell: A Passover Haggadah,” a Haggadah that is completely virtual (can be utilized at home or in a classroom) and celebrates the traditions and cultural experiences of the Jewish Diaspora. Ozeri told the Journal that a major goal of “Pictures Tell” is using imagery to tell the story of the Jewish people.

Source: https://jewishjournal.com/photographer-zion-ozeri-showcases-jewish-diversity-in-virtual-haggadah/

The Art Of Cooking – Aruk

There is nothing better than a fried crispy Aruk!

There is nothing better than a fried crispy Aruk!

Well, this Aruk resembles the Iraqi herb and potato patties; however, this version is without the potato.

Whenever I think about something like comfort food, I am thinking about eating an Aruk or even a Latke!

Not only the taste but this is usually pretty easy to make – to become the highlight of the day!

Ingredients:

3 large onions

Fresh parsley

2 eggs

100-gram minced chicken meat or alternatively minced turkey meat

Kurkuma

Salt and pepper

Flour

Cooking oil

Making the Aruk:

Start with grinding 3 onions in the blender. Loosely chop up the fresh parsley and mix it together in the bowl with the onion paste – then add the minced meat, together with a large teaspoon of salt, pepper, and kurkuma.

Mix everything together, then add the 2 eggs and continue to mix.

Add some flour until the mixture turned into a thick paste and is not too watery -however, do not add too much flour.

In a skillet or a frying pan add a generous layer of cooking oil on medium heat, when the oil is hot add scoups of the Aruk paste and let it fry on one side until golden brown and then flip.

When both sides are golden brown and crispy remove them from the oil and place them on a paper towel.

Aruk tastes great as a side dish during a nice dinner or as a perfect snack during lunchtimes.

It is always a good time to have some Aruk! it tastes best hot with some freshly squeezed lemon on top.

“Sant al-Tasqit”: Seventy Years Since The Departure Of Iraqi Jews

Source: jadaliyya.com. Seven decades after their massive exodus, the narrative about the departure of Iraqi Jews is hardly settled, not even within the displaced community itself. A continuous millennial existence in Mesopotamia was rendered impossible in the wake of a historical vortex generated by overpowering political forces and conflicting ideologies. The fall of the Ottoman Empire, the subsequent rule of British colonialism, and the emergence of Jewish and Arab nationalist movements generated internal and external political pressures on the Jewish-Iraqi community. The Zionist redefinition of Jewishness as an ethno-nationality, which was in discord with its traditional status as a religion, brought about new dilemmas and tensions, irrespective of how the Arab Jews may have viewed their Jewish affiliation. The clashing political camps of colonialism, monarchism, and communism, as well as of Zionism and Iraqi/Arab nationalism, underline the story of a community pulled in opposite directions. Consequently, Arab Jews ended up becoming the collateral damage of warring ideological zones, a diasporization born out of historically new colliding movements.

The majority of Iraqi Jews were dislocated in the wake of the U.N. partition of Palestine, the establishment of the State of Israel, and the nakba. Between 1950—1951, about 120,000 Iraqi Jews ended up departing, largely for Israel, in a process referred to as tasqit al-jinsiyya— the precondition of relinquishing Iraqi citizenship required for exiting without the possibility of return. This exodus, recalled among Iraqi Jews as “sant al-tasqit” (the year of the tasqit), is conventionally narrated as the end of the Babylonian Exile and the fulfillment of the promised messianic return to Zion. Within Jewish tradition, Babylon is a site of the Diaspora, the ultimate exilic condition epitomized in the Biblical phrase “By the waters of Babylon we laid down and wept, when we remembered Zion.” Converting religious concepts into an ethno-nationalist discourse, the Zionist notion of ‘Aliya (literally “ascendency”) has had the effect of mystifying the epic-scale cross-border movement between enemy zones. What was lived as a wrenchingly chaotic experience was emplotted as having a liturgically-sanctioned purpose culminating in a kind of happy end. Indeed, the very official term deployed for the airlifting of Iraqi Jews to Israel, “Operation Ezra and Nehemia” invoked the prophets associated with the Biblical return to Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Temple. In a more modern and secular parlance, the nomenclature celebrated the return to the legitimate “Land of origins.” Yet, such discourses downplayed the multilayered social, material, and emotional toll of the dislocation—for instance, the fact that many Iraqi Jews in Israel continued to pine for a place that had been seen simply as home. What is often recounted as the “ingathering of the exiles” and the restoration of “the Diaspora” to Jerusalem, was in fact a painfully complicated experience, an ongoing intergenerational trauma which engendered an ambivalent sense of belonging for dislocated Middle Eastern Jews. This return, within a longer historical perspective, could also be viewed as a new modality of exile, hence my inversion (in “Reflections of an Arab-Jew,” 1992): “By the waters of Zion we laid down and wept, when we remembered Babylon.”

Departing and its Discontents

In many ways, the departure is a consequence of a shifting set of geopolitical circumstances in the post-World War I era, but mostly of the facts-on-the-ground Yishuv settlements, the 1917 Balfour Declaration and the 1947 U.N. resolution to partition Palestine. The 1948 foundation of the State of Israel and the consequent massive dislocation of Palestinians to neighboring Arab countries placed indigenous Middle Eastern Jews in an acutely vulnerable position. Within the landscape of crossed-affinities, Arab Jews had to pledge allegiance to one identity articulated by two clashing movements— either “Jewish” or “Arab” —both newly defined under a novel historical banner of ethno-national affiliation. In dissonance with the traditional view of Judaism as a religion, the Zionist ethno-nationalist redefinition generated new predicaments for the community itself. Some of the Iraqi-Jewish youth came to view Israel as a promising option, especially since Arab nationalism also generated new predicaments for Arab Jews. Ironically, the Zionist view of Arabness and Jewishness as mutually exclusive gradually came to be shared by Arab nationalist discourse, placing Arab Jews on the horns of a terrible dilemma. The rigidity of both paradigms has produced the particular Jewish-Arab crisis, since neither paradigm can easily contain porous identities and multiple belongings.

The Zionist pressure to dislodge Jewish communities and end “the gola” (Diaspora) on the one hand, and the Arab nationalist gradual equation of Judaism with Zionism, on the other, brought about the eventual parting of Arab Jews from their homes. Within the rapidly shifting environment, Jews in Iraq, Egypt, Syria and so forth had to defend a Jewishness that was associated for the first time in their history not with religious culture but with colonial nationalism. These momentous events resulted in general expressions of hostility and various discriminatory measures toward indigenous Jews throughout the region. In the post-1948 era, with the deteriorating conflict in Palestine, the push-and-pull pincer movement became increasingly more intense. While the Palestinians were experiencing the nakba, Arab Jews woke up to a new world order that could not accommodate their simultaneous Jewishness and Arabness. The Orientalist split between “the Jew” and “the Arab” as two separate entities, already in embryo within colonized Middle East/North Africa, was to fully materialize with the 1947 partition. It resulted in the corollary dispossession and dispersal of Palestinians largely to Arab zones, as well as in the concomitant dislocation of Arab Jews largely to Israel. Thus, the dislocation is embedded in a new ethno-nationalist lexicon of Jews and Arabs. The historical question is whether Arab regimes bear the full weight of the responsibility for the dislocation of Arab Jews, who consequently had to be rescued by Israel; or whether, the emergence of the Zionist movement could itself be seen as igniting turmoil for Middle Eastern Jews who until the escalation of the Jewish/ Arab conflict were not in need of saving? Or, perhaps both?

Salam Hamid – The Arab Countries’ Expulsion Of The Jews Was A Disastrous Mistake

Emirati writer Salam Hamid, founder and head of the Al-Mezmaah Studies and Research Center in Dubai, published an article titled “The Cost of the Expulsion of the Arab Jews” in the UAE daily Al-Ittihad, in which he lamented the expulsion of the Jews from the Arab countries following the establishment of Israel in 1948. This expulsion, he said, was a grave mistake, since the Arab countries thereby “lost an elite population with significant wealth, property, influence, knowledge, and culture,” which could have helped them, including against Israel, and lost the potential contribution of the Jews in many spheres, especially in the financial sphere. The Arabs, he added, should have learned a lesson from the expulsion of the Jews of Spain in 1492, and from Hitler’s expulsion of the Jews of Europe, which eventually harmed the countries that lost their Jews. He stated further that antisemitism, which is deeply entrenched in Arab societies, stems from the books that teach Islamic heritage, studied in schools throughout the Arab world, and therefore called for an overhaul of the curricula in order to strengthen tolerance and banish extremism.

The following are translated excerpts from his article:

“During the years that followed the declaration of the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, most Arab countries expelled their Jewish citizens, who numbered approximately 900,000, to Israel. With this apparently strange behavior, [the Arab countries] gave a gift to the growing Hebrew nation. This makes me wonder: Why were these people deported, and what was their crime?

“Over time, [this expulsion] had disastrous repercussions, when [it turned out that] the Arabs had lost an elite population with significant wealth, property, influence, knowledge, and culture. Soon enough, the Arabs waged pointless wars against Israel, until they were defeated [in June 1967] with heavy losses. Nevertheless, the mentality of the Arab leadership persisted, as they spun conspiracy theories to their defeated peoples and sought scapegoats in order to justify their repeated defeats at the hand of Israel.

“If you ever visit Israel, you will see citizens of diverse colors, just like in the U.S. They arrived as immigrants from across the globe, of various races, and almost half of them are from Arab countries. Any intelligent person is aware that Jews had lived in Arab countries for 2,000 years before being arbitrarily expelled – yet here they are now, making up half of Israel’s citizens.

“Just a look at the number of Jews remaining in their Arab countries elucidates the difference between the past and the present. In the past, there were hundreds of thousands of Jewish citizens in Iraq, Egypt, Yemen, Syria, and the Maghreb, while today only dozens remain. Meanwhile, the Palestinians make up the largest group of asylum-seekers in the world. Some 700,000 of them left their lands after the 1948 war – not just because of the war, but because of several Arab leaders who asked them to leave the Jewish areas so that they could return after the fledgling Jewish state was destroyed. It is worth noting that in his memoir, Syria’s then-prime minister Khalid Al-‘Azm acknowledged the role played by the Arabs in convincing the Palestinians to leave – a mistake whose severity the Arabs failed to grasp, which created the Palestinian refugee crisis, and which prompted the founding of UNRWA [United Nations Relief and Works for Palestine Refugees in the Near East] in 1949.

Read more: https://www.memri.org/reports/uae-writer-arab-countries-expulsion-jews-was-disastrous-mistake

Also published on: https://jewishrefugees.blogspot.com/

Point of No Return: Jewish Refugees from Arab and Muslim Countries – One-stop blog on Jews from Arab and Muslim Countries and the Middle East’s forgotten Jewish refugees, updated daily

Visit this blog for the daily updates. The blog contains an interesting list of Sephardi/Mizrahi websites.

Mati Shemoelof – Wie man einem toten Künstler die Hasenjagd erklärt

Berliner Zeitung. Mittwoch 13. Januar 2021

Click to enlarge