Ella Shohat. Ills.: Joseph Sassoon Semah

Source: jadaliyya.com. Seven decades after their massive exodus, the narrative about the departure of Iraqi Jews is hardly settled, not even within the displaced community itself. A continuous millennial existence in Mesopotamia was rendered impossible in the wake of a historical vortex generated by overpowering political forces and conflicting ideologies. The fall of the Ottoman Empire, the subsequent rule of British colonialism, and the emergence of Jewish and Arab nationalist movements generated internal and external political pressures on the Jewish-Iraqi community. The Zionist redefinition of Jewishness as an ethno-nationality, which was in discord with its traditional status as a religion, brought about new dilemmas and tensions, irrespective of how the Arab Jews may have viewed their Jewish affiliation. The clashing political camps of colonialism, monarchism, and communism, as well as of Zionism and Iraqi/Arab nationalism, underline the story of a community pulled in opposite directions. Consequently, Arab Jews ended up becoming the collateral damage of warring ideological zones, a diasporization born out of historically new colliding movements.

The majority of Iraqi Jews were dislocated in the wake of the U.N. partition of Palestine, the establishment of the State of Israel, and the nakba. Between 1950—1951, about 120,000 Iraqi Jews ended up departing, largely for Israel, in a process referred to as tasqit al-jinsiyya— the precondition of relinquishing Iraqi citizenship required for exiting without the possibility of return. This exodus, recalled among Iraqi Jews as “sant al-tasqit” (the year of the tasqit), is conventionally narrated as the end of the Babylonian Exile and the fulfillment of the promised messianic return to Zion. Within Jewish tradition, Babylon is a site of the Diaspora, the ultimate exilic condition epitomized in the Biblical phrase “By the waters of Babylon we laid down and wept, when we remembered Zion.” Converting religious concepts into an ethno-nationalist discourse, the Zionist notion of ‘Aliya (literally “ascendency”) has had the effect of mystifying the epic-scale cross-border movement between enemy zones. What was lived as a wrenchingly chaotic experience was emplotted as having a liturgically-sanctioned purpose culminating in a kind of happy end. Indeed, the very official term deployed for the airlifting of Iraqi Jews to Israel, “Operation Ezra and Nehemia” invoked the prophets associated with the Biblical return to Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Temple. In a more modern and secular parlance, the nomenclature celebrated the return to the legitimate “Land of origins.” Yet, such discourses downplayed the multilayered social, material, and emotional toll of the dislocation—for instance, the fact that many Iraqi Jews in Israel continued to pine for a place that had been seen simply as home. What is often recounted as the “ingathering of the exiles” and the restoration of “the Diaspora” to Jerusalem, was in fact a painfully complicated experience, an ongoing intergenerational trauma which engendered an ambivalent sense of belonging for dislocated Middle Eastern Jews. This return, within a longer historical perspective, could also be viewed as a new modality of exile, hence my inversion (in “Reflections of an Arab-Jew,” 1992): “By the waters of Zion we laid down and wept, when we remembered Babylon.”

Departing and its Discontents

In many ways, the departure is a consequence of a shifting set of geopolitical circumstances in the post-World War I era, but mostly of the facts-on-the-ground Yishuv settlements, the 1917 Balfour Declaration and the 1947 U.N. resolution to partition Palestine. The 1948 foundation of the State of Israel and the consequent massive dislocation of Palestinians to neighboring Arab countries placed indigenous Middle Eastern Jews in an acutely vulnerable position. Within the landscape of crossed-affinities, Arab Jews had to pledge allegiance to one identity articulated by two clashing movements— either “Jewish” or “Arab” —both newly defined under a novel historical banner of ethno-national affiliation. In dissonance with the traditional view of Judaism as a religion, the Zionist ethno-nationalist redefinition generated new predicaments for the community itself. Some of the Iraqi-Jewish youth came to view Israel as a promising option, especially since Arab nationalism also generated new predicaments for Arab Jews. Ironically, the Zionist view of Arabness and Jewishness as mutually exclusive gradually came to be shared by Arab nationalist discourse, placing Arab Jews on the horns of a terrible dilemma. The rigidity of both paradigms has produced the particular Jewish-Arab crisis, since neither paradigm can easily contain porous identities and multiple belongings.

The Zionist pressure to dislodge Jewish communities and end “the gola” (Diaspora) on the one hand, and the Arab nationalist gradual equation of Judaism with Zionism, on the other, brought about the eventual parting of Arab Jews from their homes. Within the rapidly shifting environment, Jews in Iraq, Egypt, Syria and so forth had to defend a Jewishness that was associated for the first time in their history not with religious culture but with colonial nationalism. These momentous events resulted in general expressions of hostility and various discriminatory measures toward indigenous Jews throughout the region. In the post-1948 era, with the deteriorating conflict in Palestine, the push-and-pull pincer movement became increasingly more intense. While the Palestinians were experiencing the nakba, Arab Jews woke up to a new world order that could not accommodate their simultaneous Jewishness and Arabness. The Orientalist split between “the Jew” and “the Arab” as two separate entities, already in embryo within colonized Middle East/North Africa, was to fully materialize with the 1947 partition. It resulted in the corollary dispossession and dispersal of Palestinians largely to Arab zones, as well as in the concomitant dislocation of Arab Jews largely to Israel. Thus, the dislocation is embedded in a new ethno-nationalist lexicon of Jews and Arabs. The historical question is whether Arab regimes bear the full weight of the responsibility for the dislocation of Arab Jews, who consequently had to be rescued by Israel; or whether, the emergence of the Zionist movement could itself be seen as igniting turmoil for Middle Eastern Jews who until the escalation of the Jewish/ Arab conflict were not in need of saving? Or, perhaps both?

Read more

Photo: https://jewishrefugees.blogspot.com

Emirati writer Salam Hamid, founder and head of the Al-Mezmaah Studies and Research Center in Dubai, published an article titled “The Cost of the Expulsion of the Arab Jews” in the UAE daily Al-Ittihad, in which he lamented the expulsion of the Jews from the Arab countries following the establishment of Israel in 1948. This expulsion, he said, was a grave mistake, since the Arab countries thereby “lost an elite population with significant wealth, property, influence, knowledge, and culture,” which could have helped them, including against Israel, and lost the potential contribution of the Jews in many spheres, especially in the financial sphere. The Arabs, he added, should have learned a lesson from the expulsion of the Jews of Spain in 1492, and from Hitler’s expulsion of the Jews of Europe, which eventually harmed the countries that lost their Jews. He stated further that antisemitism, which is deeply entrenched in Arab societies, stems from the books that teach Islamic heritage, studied in schools throughout the Arab world, and therefore called for an overhaul of the curricula in order to strengthen tolerance and banish extremism.

The following are translated excerpts from his article:

“During the years that followed the declaration of the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, most Arab countries expelled their Jewish citizens, who numbered approximately 900,000, to Israel. With this apparently strange behavior, [the Arab countries] gave a gift to the growing Hebrew nation. This makes me wonder: Why were these people deported, and what was their crime?

“Over time, [this expulsion] had disastrous repercussions, when [it turned out that] the Arabs had lost an elite population with significant wealth, property, influence, knowledge, and culture. Soon enough, the Arabs waged pointless wars against Israel, until they were defeated [in June 1967] with heavy losses. Nevertheless, the mentality of the Arab leadership persisted, as they spun conspiracy theories to their defeated peoples and sought scapegoats in order to justify their repeated defeats at the hand of Israel.

“If you ever visit Israel, you will see citizens of diverse colors, just like in the U.S. They arrived as immigrants from across the globe, of various races, and almost half of them are from Arab countries. Any intelligent person is aware that Jews had lived in Arab countries for 2,000 years before being arbitrarily expelled – yet here they are now, making up half of Israel’s citizens.

“Just a look at the number of Jews remaining in their Arab countries elucidates the difference between the past and the present. In the past, there were hundreds of thousands of Jewish citizens in Iraq, Egypt, Yemen, Syria, and the Maghreb, while today only dozens remain. Meanwhile, the Palestinians make up the largest group of asylum-seekers in the world. Some 700,000 of them left their lands after the 1948 war – not just because of the war, but because of several Arab leaders who asked them to leave the Jewish areas so that they could return after the fledgling Jewish state was destroyed. It is worth noting that in his memoir, Syria’s then-prime minister Khalid Al-‘Azm acknowledged the role played by the Arabs in convincing the Palestinians to leave – a mistake whose severity the Arabs failed to grasp, which created the Palestinian refugee crisis, and which prompted the founding of UNRWA [United Nations Relief and Works for Palestine Refugees in the Near East] in 1949.

Read more: https://www.memri.org/reports/uae-writer-arab-countries-expulsion-jews-was-disastrous-mistake

Also published on: https://jewishrefugees.blogspot.com/

Point of No Return: Jewish Refugees from Arab and Muslim Countries – One-stop blog on Jews from Arab and Muslim Countries and the Middle East’s forgotten Jewish refugees, updated daily

Visit this blog for the daily updates. The blog contains an interesting list of Sephardi/Mizrahi websites.

Berliner Zeitung. Mittwoch 13. Januar 2021

Click to enlarge

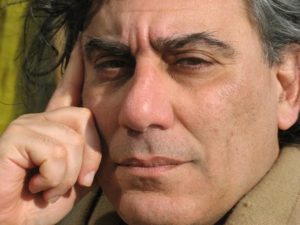

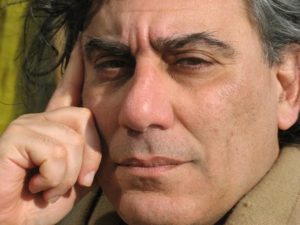

Joseph Sassoon Semah. The artist was born into a Jewish community in Baghdad, Iraq. Together with his parents, he emigrated to Israel in 1950. In the mid-1970s Semah decided to leave Israel. He lived and worked in London, Berlin, Paris and Amsterdam and regards himself as a “guest” in the Western world. His oeuvre consists of drawings, paintings, sculptures, installations, performances and texts. Photo: Linda Bouws

2021 marks the 100th anniversary of Joseph Beuys’ birth. Jewish artist Joseph Sassoon Semah explains his critical stance on the giant of postwar German art.

Berliner Zeitung 8.1.2021. Berlin/Amsterdam.

This year Germany will celebrate 100 years since the birth of Joseph Beuys, one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Beuys was considered the healer and shaman of postwar Germany.

The Amsterdam-based, Jewish artist Joseph Sassoon Semah was not invited to the celebration, despite his rich artistic dialogue with Beuys’ art.

Semah, the grandchild of the last rabbi from Baghdad, who emigrated to Israel and later to the Netherlands, argues that even if he had applied to participate in the 100-year celebration of Beuys, he believes he would have been rejected. He decided, instead, to create alternative artistic events in several German and Dutch institutions.

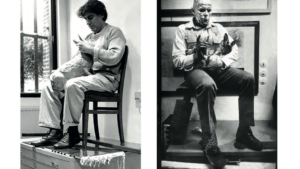

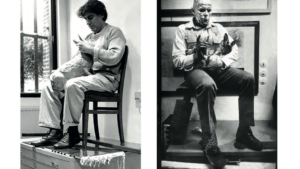

On 26 November 1965, Beuys conducted a performance in a gallery holding a dead rabbit in his arms. He named the performance: “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare”. Beuys died on January 23, 1986. And on 24 February 1986, Semah created his own performative answer to Beuys with the installation: “How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist”.

In our conversation, Semah states: “Well, they are not going to criticise him when they celebrate these 100 years. That’s why we talked with Arie Hartog, director of the Gerhard Marcks Haus museum in Bremen. We decided to answer with an art project that will be presented in the Gerhard Marcks Haus, the University of Amsterdam, the Jewish Museum of Amsterdam and Goethe Institute of Holland. The event will be showing different critical points, mainly from my perspective not only as an artist that has been inspired by his work. I will elaborate on my experience of his work as a Jew.”

Mati Shemoelof: For those who do not know, “hare hunting” was a euphemism for killing Jews by the Gestapo during the Holocaust. Your performance in 1986 was part of an exhibition in the Gerhard Marcks Haus, in Bremen, that once belonged to the Gestapo headquarters.

Joseph Beuys died on 23 January 1986 and my birthday took place about a month after his death. Now, because he died, I could transfer the title “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” to the title of my performance: “How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist”. Germany was not the Germany of today. Beuys was busy with reconstruction of “Germania” and holding us, the Jews, as a dead hare. The question should be different. In my opinion, Beuys only cared about his own wounds.

You did a public confession for your actions as an Israeli soldier in Amsterdam but Beuys never confessed to his Nazi past. In your eyes, why didn’t he?

It surprised me that Joseph Beuys didn’t do a confession about his involvement with the Nazi army. I wanted to criticise that. In 1936, Beuys was a member of the Hitler Youth. I know that it was compulsory. But actually, later on, in 1941, Beuys volunteered for the Luftwaffe (air force). In 1942, Beuys was stationed in Crimea and was a member of various combat bomber units. He actually volunteered. Nobody asked him. He dropped bombs on innocent people. In his brilliant way, Beuys transformed his subjectivity to the suffering of the German soldier in the Second World War. In that odd way, Beuys became a victim.

One of the famous phrases of Beuys is “every man is an artist”. Beuys was part of the Düsseldorf art school where he demanded that the school open its door to anyone who wanted to be an artist. The art school kicked him out because of his radical demands. Can you elaborate more about your artistic answer to Beuys?

I created a similar environment in my performance in Amsterdam. I sat on an aluminum office cabinet with a chair that belonged to a Gestapo waiting room in Berlin. I had a wine glass on the window. A neon light under my chair. In between copper plates I had a Talit (a Jewish prayer shawl). I was holding a hare which I cast from bronze. One of the code words of the Nazi Wehrmacht was “jagt den Hasen”(“hunt the rabbits”). And they meant: we are going to hunt the Jews. Beuys could have chosen any other animal. But of course, he chose the hare. He walked with the dead rabbit into the gallery, where he did the performance and explained to him the paintings that he did with his own blood in a language that nobody understood. I concluded that he tried to speak with the hare in Hebrew.

Joseph Sassoon Semah created the performance “How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist” (left), answering Joseph Beuys’ “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” (right).

The art historian and curator Gideon Ofrat wrote that you converted Beuys to Judaism. In one hand, you were holding the rabbit and the other was placed on your forehead to symbolise pain and at the same time deep thinking. There was a neon light on the wall, symbolising God’s eternal light that answers the cross that was underneath the chair and the wine glass – symbolising the cruxifiction of Jesus Christ. Have you met Beuys?

I met him twice. Once in Berlin, at the National Gallery. He was a kind man. He invited me to his home but I didn’t go. We met again, also in Berlin, just before I left for Amsterdam at the beginning of the 1980s, and talked for half an hour. Yes, he was aware of my work, but he was the clean, pure face of Germany after the Second World War – and I was just a young artist.

It sounds like you have a love-hate relationship with him. On one hand, so many of your artworks are in dialogue with his art. On the other hand, you can’t stand the position that he took as a victimiser in German and European art. And so, I have to ask you, why didn’t you go to his house?

Maybe I wasn’t really occupied with him at that time. Maybe postwar Germany wasn’t really in my focus. Around 1982, I left Berlin and it was easier for me to work in Amsterdam. In 1982, I wrote a letter to Albrecht Dürer [German painter, 1471-1582] and explained to him my thoughts on Luther and Beuys.

If Beuys was alive, how do you imagine his reaction to the Jewish performance you created in reaction to him?

In his ironic way, he would have rejected me. He did already with the hare – holding me, a dead Jew – in his hands.

Hans Peter Reiegel, one of Beuys’ biographers, mentioned that many of Beuys’ patrons and friends hid their Nazi past. From Beuys’ incident in the Luftwaffe – his plane was shot down – Beuys fashioned the myth that he was rescued by nomadic Tatar tribesmen, who wrapped his broken body in animal fat and nursed him back to health. According to his version, they told him: “Nje nemiecky, du Tatar” – “You are not a German, you are a Tatar”. Records state that Beuys was conscious, that he was recovered by a German search commando, and there were no Tatars in the village at that time. But people still believe his version of the story and that Beuys could transform German society. Do you believe in the power of Beuys’ transformation?

Beuys was a soldier who returned from war and starting to create through his personal pain. He transformed himself from a victimiser to a victim. I don’t really trust this social order he created.

Beuys had an enormous influence on Israeli art in the 1970s when it comes to healing – especially when it comes to selected works of Tamar Getter, David Ginaton, Moshe Mizrahi and others. In 1973, David Ginaton went to Josef Beuys’ home in Düsseldorf, after not finding him at the academy. He knelt in front of the artist’s house as if he was a god.

When Ginaton kneeled in front of the house of Beuys, I found it so sad to see. I guess it should be the other way around. And you can see the power of symbols. I don’t know why he did it. Ginaton was an Israeli soldier who was in Germany. Maybe the fascination of soldiers was connecting them.

Why do you take a different perspective to that of the European Israeli artist? Do you connect it to your Baghdad origins? Is the entering of the Nazi ideology into Iraq connected in some underlying way to your criticism of Beuys’ work? You were born in Baghdad in 1948. Your grandfather, Hacham Sassoon Kadoorie, was the chief rabbi of Baghdad’ s Jewish community until his passing in 1971, even after they had all emigrated to Israel.

Of course. It is not only about the Germans. It is about Western ideology. And it affects the whole cultural world, including the works of Beuys. And of course, indirectly, it affects the life of Jews in the Arab world. The word “antisemitism” can’t be taken seriously in the Arab lands because they are also semitic. Well, I am a Babylonian Jew and I don’t succumb to all of the construction of silence around Beuys. I am free from it. I can read it in a totally new way. It took me time.

–

This article was submitted as part of our Open Source initiative. With Open Source, Berliner Verlag gives freelance writers and anyone interested the opportunity to contribute articles containing relevant content and written to a professional standard. Selected contributions will be published and paid for.

This article is subject to the Creative Commons licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). It may be freely reused by the general public for non-commercial purposes on the condition that it remains unaltered and that the author and Berliner Zeitung are attributed.

Smadar Lavie

Photo:en.wikipedia.org

This paper analyzes the failure of Israel’s Ashkenazi (Jewish, of European, Yiddish-speaking origin) feminist peace movement to work within the context of Middle East demographics, cultures, and histories and, alternately, the inabilities of the Mizrahi (Oriental) feminist movement to weave itself into the feminist fabric of the Arab world.

Although Ashkenazi elite feminists in Israel are known for their peace activism and human rights work, from the Mizrahi perspective their critique and activism are limited, if not counterproductive. The Ashkenazi feminists have strategically chosen to focus on what Edward Said called the Question of Palestine—a well funded agenda that enables them to avoid addressing the community-based concerns of the disenfranchised Mizrahim. Mizrahi communities, however, silence their own feminists as these activists attempt to challenge the regime or engage in discourse on the Question of Palestine. Despite historical changes, the Ashkenazi-Mizrahi distinction is a racialized formation so resilient it manages to sustain itself through challenges rather than remain a frozen dichotomy.

Source: Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies · April 2011

Download Full Text: Lavie_MizrahiFeminismandtheQuestionofPalestine

Amira Hess. Ills.: Joseph Sassoon Semah

And As Far As What I Wanted

And as far as I wanted to further explain to you

what every sign says.

After all, surely you understand the way of colors,

the gilded light, the chlorophyll light,

the light of pain and the light of need and vigilant light

and the light of an arc in the sky

splitting through again to seed with drops of sun suddenly burning

the essence of yearning.

The light of the eyes of the dogs

shine loyalty in the dark to their masters.

The growing shadow of darkness placed late

in fading time.

How the radiant blackness disseminates its night

And how the arrows’ whiteness smothers its light

How everything is lucid from so much pain.

– Translated from the Hebrew by Yonina Borvick

From And The Moon Drips Madness

There was a time

when I’d have said:

I won’t defile myself

with this contemptible Orient,

I’ll relegate my ancestral

home to oblivion,

my mother’s owlish visage

weeping over the ruins,

my father’s face like a cherub-

the Lord – graced him not.

And I also said:

The West, for instance,

Has no cares to its spirit,

well-done within, singed to the shrouds.

East and West I’ll set out in a strong beat

for there is no ark

to bestir myself, if daughter

departs more spirit

to make eagles soar.

– Translated from the Hebrew by Ammiel Alcalay

Then Slake Him From

Then slake him from

A wineskin flowing and a wineskin of milk and a wineskin of loveliness

Kiss and weep, for the time of loving has come.

Woman-dust-earth seeped into the lust in his touch

Keen after him

Kiss his footprints

Do not bind his freedom.

Place him as a cock

Rising early, at sun’s fire,

As a madman, his body screaming desire.

– Translated from the Hebrew by Marsha Weinstein

Read more