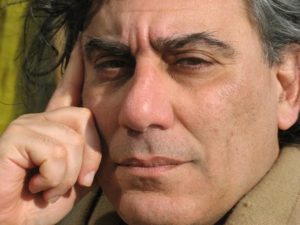

Joseph Sassoon Semah. The artist was born into a Jewish community in Baghdad, Iraq. Together with his parents, he emigrated to Israel in 1950. In the mid-1970s Semah decided to leave Israel. He lived and worked in London, Berlin, Paris and Amsterdam and regards himself as a “guest” in the Western world. His oeuvre consists of drawings, paintings, sculptures, installations, performances and texts. Photo: Linda Bouws

2021 marks the 100th anniversary of Joseph Beuys’ birth. Jewish artist Joseph Sassoon Semah explains his critical stance on the giant of postwar German art.

Berliner Zeitung 8.1.2021. Berlin/Amsterdam.

This year Germany will celebrate 100 years since the birth of Joseph Beuys, one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Beuys was considered the healer and shaman of postwar Germany.

The Amsterdam-based, Jewish artist Joseph Sassoon Semah was not invited to the celebration, despite his rich artistic dialogue with Beuys’ art.

Semah, the grandchild of the last rabbi from Baghdad, who emigrated to Israel and later to the Netherlands, argues that even if he had applied to participate in the 100-year celebration of Beuys, he believes he would have been rejected. He decided, instead, to create alternative artistic events in several German and Dutch institutions.

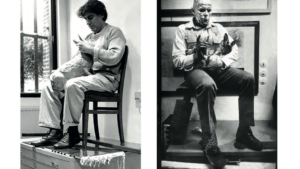

On 26 November 1965, Beuys conducted a performance in a gallery holding a dead rabbit in his arms. He named the performance: “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare”. Beuys died on January 23, 1986. And on 24 February 1986, Semah created his own performative answer to Beuys with the installation: “How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist”.

In our conversation, Semah states: “Well, they are not going to criticise him when they celebrate these 100 years. That’s why we talked with Arie Hartog, director of the Gerhard Marcks Haus museum in Bremen. We decided to answer with an art project that will be presented in the Gerhard Marcks Haus, the University of Amsterdam, the Jewish Museum of Amsterdam and Goethe Institute of Holland. The event will be showing different critical points, mainly from my perspective not only as an artist that has been inspired by his work. I will elaborate on my experience of his work as a Jew.”

Mati Shemoelof: For those who do not know, “hare hunting” was a euphemism for killing Jews by the Gestapo during the Holocaust. Your performance in 1986 was part of an exhibition in the Gerhard Marcks Haus, in Bremen, that once belonged to the Gestapo headquarters.

Joseph Beuys died on 23 January 1986 and my birthday took place about a month after his death. Now, because he died, I could transfer the title “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” to the title of my performance: “How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist”. Germany was not the Germany of today. Beuys was busy with reconstruction of “Germania” and holding us, the Jews, as a dead hare. The question should be different. In my opinion, Beuys only cared about his own wounds.

You did a public confession for your actions as an Israeli soldier in Amsterdam but Beuys never confessed to his Nazi past. In your eyes, why didn’t he?

It surprised me that Joseph Beuys didn’t do a confession about his involvement with the Nazi army. I wanted to criticise that. In 1936, Beuys was a member of the Hitler Youth. I know that it was compulsory. But actually, later on, in 1941, Beuys volunteered for the Luftwaffe (air force). In 1942, Beuys was stationed in Crimea and was a member of various combat bomber units. He actually volunteered. Nobody asked him. He dropped bombs on innocent people. In his brilliant way, Beuys transformed his subjectivity to the suffering of the German soldier in the Second World War. In that odd way, Beuys became a victim.

One of the famous phrases of Beuys is “every man is an artist”. Beuys was part of the Düsseldorf art school where he demanded that the school open its door to anyone who wanted to be an artist. The art school kicked him out because of his radical demands. Can you elaborate more about your artistic answer to Beuys?

I created a similar environment in my performance in Amsterdam. I sat on an aluminum office cabinet with a chair that belonged to a Gestapo waiting room in Berlin. I had a wine glass on the window. A neon light under my chair. In between copper plates I had a Talit (a Jewish prayer shawl). I was holding a hare which I cast from bronze. One of the code words of the Nazi Wehrmacht was “jagt den Hasen”(“hunt the rabbits”). And they meant: we are going to hunt the Jews. Beuys could have chosen any other animal. But of course, he chose the hare. He walked with the dead rabbit into the gallery, where he did the performance and explained to him the paintings that he did with his own blood in a language that nobody understood. I concluded that he tried to speak with the hare in Hebrew.

Joseph Sassoon Semah created the performance “How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist” (left), answering Joseph Beuys’ “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” (right).

The art historian and curator Gideon Ofrat wrote that you converted Beuys to Judaism. In one hand, you were holding the rabbit and the other was placed on your forehead to symbolise pain and at the same time deep thinking. There was a neon light on the wall, symbolising God’s eternal light that answers the cross that was underneath the chair and the wine glass – symbolising the cruxifiction of Jesus Christ. Have you met Beuys?

I met him twice. Once in Berlin, at the National Gallery. He was a kind man. He invited me to his home but I didn’t go. We met again, also in Berlin, just before I left for Amsterdam at the beginning of the 1980s, and talked for half an hour. Yes, he was aware of my work, but he was the clean, pure face of Germany after the Second World War – and I was just a young artist.

It sounds like you have a love-hate relationship with him. On one hand, so many of your artworks are in dialogue with his art. On the other hand, you can’t stand the position that he took as a victimiser in German and European art. And so, I have to ask you, why didn’t you go to his house?

Maybe I wasn’t really occupied with him at that time. Maybe postwar Germany wasn’t really in my focus. Around 1982, I left Berlin and it was easier for me to work in Amsterdam. In 1982, I wrote a letter to Albrecht Dürer [German painter, 1471-1582] and explained to him my thoughts on Luther and Beuys.

If Beuys was alive, how do you imagine his reaction to the Jewish performance you created in reaction to him?

In his ironic way, he would have rejected me. He did already with the hare – holding me, a dead Jew – in his hands.

Hans Peter Reiegel, one of Beuys’ biographers, mentioned that many of Beuys’ patrons and friends hid their Nazi past. From Beuys’ incident in the Luftwaffe – his plane was shot down – Beuys fashioned the myth that he was rescued by nomadic Tatar tribesmen, who wrapped his broken body in animal fat and nursed him back to health. According to his version, they told him: “Nje nemiecky, du Tatar” – “You are not a German, you are a Tatar”. Records state that Beuys was conscious, that he was recovered by a German search commando, and there were no Tatars in the village at that time. But people still believe his version of the story and that Beuys could transform German society. Do you believe in the power of Beuys’ transformation?

Beuys was a soldier who returned from war and starting to create through his personal pain. He transformed himself from a victimiser to a victim. I don’t really trust this social order he created.

Beuys had an enormous influence on Israeli art in the 1970s when it comes to healing – especially when it comes to selected works of Tamar Getter, David Ginaton, Moshe Mizrahi and others. In 1973, David Ginaton went to Josef Beuys’ home in Düsseldorf, after not finding him at the academy. He knelt in front of the artist’s house as if he was a god.

When Ginaton kneeled in front of the house of Beuys, I found it so sad to see. I guess it should be the other way around. And you can see the power of symbols. I don’t know why he did it. Ginaton was an Israeli soldier who was in Germany. Maybe the fascination of soldiers was connecting them.

Why do you take a different perspective to that of the European Israeli artist? Do you connect it to your Baghdad origins? Is the entering of the Nazi ideology into Iraq connected in some underlying way to your criticism of Beuys’ work? You were born in Baghdad in 1948. Your grandfather, Hacham Sassoon Kadoorie, was the chief rabbi of Baghdad’ s Jewish community until his passing in 1971, even after they had all emigrated to Israel.

Of course. It is not only about the Germans. It is about Western ideology. And it affects the whole cultural world, including the works of Beuys. And of course, indirectly, it affects the life of Jews in the Arab world. The word “antisemitism” can’t be taken seriously in the Arab lands because they are also semitic. Well, I am a Babylonian Jew and I don’t succumb to all of the construction of silence around Beuys. I am free from it. I can read it in a totally new way. It took me time.

–

This article was submitted as part of our Open Source initiative. With Open Source, Berliner Verlag gives freelance writers and anyone interested the opportunity to contribute articles containing relevant content and written to a professional standard. Selected contributions will be published and paid for.

This article is subject to the Creative Commons licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). It may be freely reused by the general public for non-commercial purposes on the condition that it remains unaltered and that the author and Berliner Zeitung are attributed.

Smadar Lavie

Photo:en.wikipedia.org

This paper analyzes the failure of Israel’s Ashkenazi (Jewish, of European, Yiddish-speaking origin) feminist peace movement to work within the context of Middle East demographics, cultures, and histories and, alternately, the inabilities of the Mizrahi (Oriental) feminist movement to weave itself into the feminist fabric of the Arab world.

Although Ashkenazi elite feminists in Israel are known for their peace activism and human rights work, from the Mizrahi perspective their critique and activism are limited, if not counterproductive. The Ashkenazi feminists have strategically chosen to focus on what Edward Said called the Question of Palestine—a well funded agenda that enables them to avoid addressing the community-based concerns of the disenfranchised Mizrahim. Mizrahi communities, however, silence their own feminists as these activists attempt to challenge the regime or engage in discourse on the Question of Palestine. Despite historical changes, the Ashkenazi-Mizrahi distinction is a racialized formation so resilient it manages to sustain itself through challenges rather than remain a frozen dichotomy.

Source: Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies · April 2011

Download Full Text: Lavie_MizrahiFeminismandtheQuestionofPalestine

Amira Hess. Ills.: Joseph Sassoon Semah

And As Far As What I Wanted

And as far as I wanted to further explain to you

what every sign says.

After all, surely you understand the way of colors,

the gilded light, the chlorophyll light,

the light of pain and the light of need and vigilant light

and the light of an arc in the sky

splitting through again to seed with drops of sun suddenly burning

the essence of yearning.

The light of the eyes of the dogs

shine loyalty in the dark to their masters.

The growing shadow of darkness placed late

in fading time.

How the radiant blackness disseminates its night

And how the arrows’ whiteness smothers its light

How everything is lucid from so much pain.

– Translated from the Hebrew by Yonina Borvick

From And The Moon Drips Madness

There was a time

when I’d have said:

I won’t defile myself

with this contemptible Orient,

I’ll relegate my ancestral

home to oblivion,

my mother’s owlish visage

weeping over the ruins,

my father’s face like a cherub-

the Lord – graced him not.

And I also said:

The West, for instance,

Has no cares to its spirit,

well-done within, singed to the shrouds.

East and West I’ll set out in a strong beat

for there is no ark

to bestir myself, if daughter

departs more spirit

to make eagles soar.

– Translated from the Hebrew by Ammiel Alcalay

Then Slake Him From

Then slake him from

A wineskin flowing and a wineskin of milk and a wineskin of loveliness

Kiss and weep, for the time of loving has come.

Woman-dust-earth seeped into the lust in his touch

Keen after him

Kiss his footprints

Do not bind his freedom.

Place him as a cock

Rising early, at sun’s fire,

As a madman, his body screaming desire.

– Translated from the Hebrew by Marsha Weinstein

Read more

The Schnitzel has been brought by the European Jews to Israel, and currently everyone enjoys it!

The Schnitzel has been brought by the European Jews to Israel, and currently everyone enjoys it!

I visited many households in Israel, and at any time of the day or night one can enjoys a Chicken Schnitzel. The Israeli version of Schnitzel is recognizable because of the white sesame seeds which cover the meat.

True, it might not be the most exciting or unique dish out there, and yet, it is definitely a staple in Israel when compared to the hummus.

Ingredients:

2 to 4 chicken breasts depending on how much you want to make (one can substitute the chicken breasts with chicken thighs for a more juicy fatty version)

flour

2 or 3 eggs

breadcrumbs (panko breadcrumbs are nice for a pleasant crisp)

salt & pepper

paprika powder

sesame seeds

cayenne pepper (if you want it a bit more spicy)

lemon wedges

Preparing the chicken:

First, you should cut the chicken into thin flat slices; you can use a butterfly cutting technique to make them bigger and flatter.

When the flat pieces of chicken are ready, place them in between two sheets of plastic and with a mallet or a hammer give them a good pounding until they are even and flat – you should focus mainly on the thicker parts.

Next, you should prepare three bowls, fill the first bowl with flour, and in the second bowl place two eggs or three eggs and beat them.

As to the third bowl, you should fill it with bread crumbs, add sesame seeds, salt, pepper, and paprika – optionally, you can use cayenne pepper – mix all the ingredients together.

Now, season lightly the chicken with salt and pepper, dredge chicken in flour until the surface is completely covered and shake off the excess flour.

Next, dip the chicken in beaten eggs mixture and then roll it through the breadcrumbs to coat, and make sure the chicken is completely covered and then lightly shake off the excess breadcrumbs.

Repeat the process until all the chicken pieces are done.

Cook the chicken:

Add a healthy layer of cooking oil to a hot skillet, make sure it is not too hot, after all, you do not want the oil to be smoking.

Softly place the pieces of chicken into the hot oil.

Fry the schnitzels for 2 or 3 minutes on each side, until golden brown.

After frying the schnitzel, let it rest on paper towels for a couple of seconds.

Chicken Schnitzel is a perfect dish for lunches, or in the evening!

Very enjoyable with a simple Israeli salad, and some pita bread with Hummus.

Serve with lemon wedges – remember, the squeeze lemon adds so much flavor to the schnitzel.

Tal Nitzan. Ills.: Joseph Sassoon Semah

I remember Etty Hillesum

Did she still whisper

“Why anticipate trouble”

when transported from Westerbork

to Auschwitz in Wagon Number 12,

“They should be exterminated like fleas,

those petty fears of the future”

as her future rushed towards her

to exterminate her?

Maybe I should pause, retreat

or at least recite

“Why anticipate joy”

as I hurry past the yellow squares of life

that once were far and sealed

and tonight open towards me

to let me in and out as I wish

while a silly hope for happiness

sways like a jug, too large,

on my head

“An interrupted life”, the diaries of Etty Hillesum, 1941-1943

Translation: Tal Nitzan & Vivian Eden

The third child

I’m your unknown child.

I’m the negative

between your two blue-eyed children

who radiate against my darkness.

I’m your forgotten, your vanished, I’m your

kicked away.

I kneel – while they close their eyes

and reach out their hands for the gift –

as if begging for the blow

that will not come.

I feed on the cocoa trail they leave,

on the rustle of wrappings.

I shrink at night into the corner

of their beds, where tiny stuffed animals

encircle them

like shelter against evil,

lurking for the nocturnal ritual,

when you step on my toes unseeing,

and bend to smoothe their plump blankets.

When you close your eyes

(green like mine!)

I’ll creep under your eyelids and murmur:

“Mommy”.

If you try to banish the nightmare of my face

you’ll find out, shamefully,

you don’t even know my name.

Translation: Tal Nitzan & Vivian Eden

Tal Nitzan was born in Jaffa, Israel, and has lived in Argentinia, Colombia, and U.S.A. (NY). She currently lives in Tel Aviv.

She is an awardwinning poet, writer, translator of Hispanic literature and editor.

Tal Nitzan published numerous poetry books.

https://www.facebook.com/IsraelinNY/

Shelley Elkayam – Ills.: Joseph Sassoon Semah

Current Sufism in Israel El Tarika El Ibrahimiyyah – The Way of Abraham – A Bridge between Middle East Religions

Introduction

I wish to thank the University of Goettingen for inviting me to lecture at the Intercultural Theology program on the Current Sufism in Israel and on Sephardic Ultra-Orthodoxy in Israel.

I will begin by introducing my subject with some historical background. Then, I would like to make a reference to the specific audience sitting here right now because it is a very special audience. On the one hand, it is German; on the other, it is an international audience. So we have to consider how do we speak to such a local yet global group.

At that point, I will present the thesis of this lecture.

So, let us now discuss the issue of the Sephardic Jews. Who are they?

The reason why one knows so little about the Sephardic or Oriental Jews is also a matter of scientific concern for those of us who study Intercultural Theology. Thus, let us have a quick look at a long and serious matter such as The Stage of History.

Yes, stage as in Stage Theater, with the very writers who write the script and the very actors who play the protagonists and the very hegemonic audience who wish to see themselves on stage, or else the very far exotic other. Then we shall move forward to have an idea about the intellectual assets of the ISRAEL Sufi way and perhaps if time allows, we shall read during our workshop some of the devotional texts studied by the Israel Sufi Way, such as El-Ghazali. So hopefully you should have some taste regarding the intercultural Theology that is bridging between religions in the Middle East today, and we shall conclude with that today.

Background

In the Jewish State of Israel, Sufi activity had been almost eliminated by the disruption of the War in 1948, partly revived after the renewal of contacts between Palestinians in Israel and in the West Bank and Gaza “in the wake of 1967 Arab Israeli War” and suppressed in the Second Intifada, also known as the Oslo War and the Al- Aqsa Intifada (2000 to 2005). This Intifada raged between the 20th and the 21st century.

In this lecture I focus on Sufism in Israel as manifested by The Israeli Sufi Way. The Israeli Sufi Way is known as The Sufi Way of Abraham. In Hebrew – One of Israel’s two national languages, it sounds Derekh Avraham (אברהם דרך). In Arabic, the other national language, it sounds Al-Tariqah Ibrahimiyyah or Ibrahimiyyah-Al (א-טַּרִיקַה אל-אִבְּרַאהִימִיַּה) / الإبراهميّة الطّريقة ).

The members of the Israeli Sufi Way come from various circles: Academy, conservative and orthodox Rabbinic institutes and leadership of other Sufi brotherhoods of Israel: Qadiriyyah, Shadhiliyyah-Yashrutiyyah and Naqshbandiyyah.

Ibrahimiyyah defines itself (2014) publicly as an inter-religious movement encouraging dialogue between Jews, Christians and Muslims. This inter-religious character is a “post-Sufi” strategy as well as a spiritual response to the particular modern European challenges of the State of Israel, tackling the Israeli East-West debate.

The Sufi leadership of the 3 Muslim brotherhoods responded to the challenge of the peculiar circumstances in which they live in the Middle East, by joining the Ibrahimiyyah and establishing it as the Israeli Sufi Way of Abraham.

This Israeli Sufi brotherhood was created during the 1990s right at the end of the twentieth century. Public activity gathered momentum during the first decade of the twenty first century, with a double mission of both peace between Jews and Muslims, and spiritual search for Medieval Jewish Sufi roots. Special attention is given to 16th century Safed (in the Land of Israel) and of Egypt and North Africa and since the Sufi festival in 2010 also to Indian Jewish Sufism of perhaps 12 century.

Read more