‘Be Realistic, Demand The Impossible!’ ~ How The Events Of 1968 Transformed French Society

No Comments yet

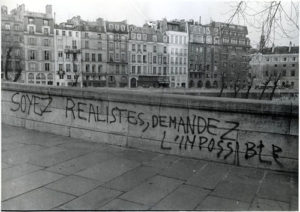

France. Paris et Banlieue. Graffiti, bombages, inscription et affiche dans les fac et les rue autour de mai 1968

This week, 50 years ago, France was going through the biggest labour strike in its history. Two-thirds of its labour force were out in the streets demanding better working conditions. Workers had taken control of factories, set up barricades, organised sit-ins and fought off attempts by the police to disperse them. Thousands of students who had rebelled against conservative university administrations had also joined them.

By the end of the week, French President Charles de Gaulle would disappear from Paris, seeking support from the French army for a military intervention against the strikers.

Tanks, however, would not roll down the streets of Paris that year. De Gaulle would decide instead to dissolve the parliament and call for general elections. Although the crisis would subside by June, the events of May would have a major ripple effect in space and time.

Today, 50 years later, we can honestly say that what happened in May 1968 – from Paris to Prague, and from Mexico to Madrid – was the most significant political development that took place in the West during this tumultuous decade.

The 1960s witnessed the emergence of the second chapter of the civil rights movement in the US, the re-radicalisation of the labour force throughout Western Europe, women’s rights, and gay rights. But the political scene in the 1960s was marked above all else by the Vietnam War and the protests of 1968 against political elites, authoritarianism, and the bureaucratisation of everyday life.

They were spontaneous, explosive protests of rebellious spirits that changed fundamentally the political, social and cultural landscape of entire nations, although no revolution ever occurred

The May ’68 protests had the most dramatic impact in the country that had experienced one of the greatest social upheavals in western history, the French Revolution.

And it all started, as most challenges to the status quo do, by the youth.

French students who came of age with politics and philosophy normalising resistance and personal responsibility (Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialist-Marxism reigned supreme throughout the 1960s) rebelled against a highly traditional and even archaic educational system, but their protests soon developed into a fight against the capitalist system and the whole bourgeois model, resting on a “patriarchal-authoritarian sexual order” came under attack.

The student protests in France actually started in 1967, at Nanterre University, against restrictions that prevented male students from visiting female colleagues at their dorm.

A series of events that followed in the first months of 1968, including the arrest of several students over the explosion of an American Express office in central Paris, helped to further radicalise the youth. The protests spread to other universities after Nanterre University was shut down by its dean in a desperate attempt to prevent the further escalation of protests.

When the Sorbonne was also closed following clashes between students and police, a major march was scheduled for May 10 which led to the Night of the Barricades.

What followed is well-traversed territory by journalists and historians alike.

Thousands of students clashed in the early hours of May 11, with hundreds of riot police who used tear gas and beat students with truncheons. By the time the sun came up, hundreds of students had been hospitalised and some 500 had been arrested.

By then, the battle was not merely over sexual repression and educational reform. It was about a demand for deep social transformation and that demand was accompanied by inexorable anger over the hypocrisy of a conservative, authoritarian system, the legacy of the Algerian independence war, and, yes, even the legacy of collaboration with the Nazis during World War II.

The French student protests of May 1968 were indeed about producing a national catharsis in the context of a rapidly changing world.

As such, the slogan that best captures the spirit of the May 1968 protests was the one that first appeared mainly on the walls of Paris and read as follows: “Be realistic, demand the impossible.”

A few days after the Night of the Barricades, millions of workers walked off their job and joined the nation-wide strike. The French Communist Party and its allied labour union organisation, the Confederation Generale du Travail, did their best to keep workers apart from students and to block any potential path to a revolution.

Indeed, like all potential revolutions, this one was also betrayed from within.

To the surprise of many at the time, the May 1968 protests ended in early June when the trade unions accepted a government deal which included generous wage hikes and a shorter work week. Soon afterwards, the student protests also fizzled out.

Nonetheless, the May 1968 protests changed France in fundamental ways.

For starters, the rage behind the protests led to an end of Gaullism, a highly conservative, state-oriented ideology, and converted the country into an open, tolerant and secular society.

Thanks to the spirit and the aims of the May ’68 protests, women became socially liberated (before, French women could not even wear pants at work and had to have a husband’s permission to open a bank account), while worker militancy secured better conditions of life and work.

It is of little surprise therefore that conservative political leaders in France (and elsewhere) continue to this day to blame the legacy of May 1968 for the overthrow of conservative norms and values.

This spirit of change and openness, however, has not really survived to present times. Today’s France has turned inward, resisting change and embracing xenophobia. French democracy has plunged into crisis.

Students and workers remain politically active, but they lack the rage of their predecessors and are in need of a new vision for the future.

Does this mean then that the legacy of May 1968, like that of the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, is now just a memory? Perhaps. But the course of history has fooled us before, and it can fool us again.

In a world of dire need for radical change and social justice, the May revolts of 1968 could still become a source of inspiration. All that it takes is a new generation of rebellious spirit, bold enough to say “Be realistic, demand the impossible!”

Previously published on https://www.aljazeera.com/

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply