Riches To Rags To Virtual Riches: When Mizrahi Artists Said ‘No’ To Israel’s Pioneer Culture

No Comments yetUpon their arrival in Israel, Mizrahi Jews found themselves under a regime that demanded obedience, even in cultural matters. All were required to conform to an idealized pioneer figure who sang classical, militaristic ‘Hebrew’ songs. That is, before the ‘Kasetot’ era propelled Mizrahi artists into the spotlight, paving the way for today’s musical stars. Part two of a musical journey beginning in Israel’s Mizrahi neighborhoods of the 1950s and leading up to Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf. Read part one here.

Our early encounter with Zionist music takes place in kindergarten, then later in schools and the youth movements, usually with an accordionist in tow playing songs worn and weathered by the dry desert winds. Music teachers at school never bothered with classical music, neither Western nor Arabian, and traditional Ashkenazi liturgies – let alone Sephardic – were not even taken into account. The early pioneer music was hard to stomach, and not only because it didn’t belong to our generation and wasn’t part of our heritage. More specifically, we were gagging on something shoved obsessively down our throat by political authority.

Our “founding fathers” and their children never spared us any candid detail regarding the bodily reaction they experience when hearing the music brought here by our fathers, and the music we created here. But not much was said regarding the thoughts and feelings of Mizrahi immigrants (nor about their children who were born into it) who came here and heard what passed as Israeli music, nor about their children who were born into it. Had there been a more serious reckoning from our Mizrahi perspective, as well as the perspective of Palestinians, mainstream Israeli culture might have been less provincial, obtuse and mediocre than what it is today.

Israeli radio stations in the 60s and 70s played songs by military bands, or other similar bands such as Green Onion or The Roosters. There were settler songs such as “Eucalyptus Orchard” with its veiled belligerence, and other introverted war songs, monotonous and stale, inspiring depressive detachment. For example, take “He Knew Not Her Name,” sung here by casual soldiers driving in a jeep through ruins of an Arab village, or the pompous “Tranquility.” When these songs burst out in joy, as is the case with “Carnaval BaNahal,” it comes out loud and vulgar. “The Unknown Squad,” composed by Moshe Vilensky, written by Yechiel Mohar and performed by the Nahal Band in 1958, always reminded me of the terrifying military march music I used to hear on Arab radio stations as a child. As far as the Arabs were concerned, these tunes represented trivial propaganda, not the cultural mainstream. However, in Israel, the Nahal Band was lauded as the country’s finest for more than two decades. Thanks to YouTube, we can now revisit the footage and see them marching, eyes livid and intimidating, faces blank.

Shoshana Damari’s voice, which was supposed to cushion our shocking encounter with this music, only made it worse. Every time her voice would boom out on early 70s public television my father would stretch an ironic smile under his thin Iraqi mustache and let out an expressive, “ma kara?” (“what’s the big deal?”), in sardonic astonishment of the wartime-chanteuse’s bombastic pomp.

It’s not hard to understand why revolutionary Zionists would have their hearts set on a patriotic military musical taste, complete with marching music and Eastern European farming songs fitted for a newfound belligerent lifestyle. But this dominating attitude would prove shocking to Mizrahi Jews, and the musicians among them, who took an active role in the greater Arab music scene (for more on the topic read part one of this series). These musicians were accustomed to the cultural freedoms they enjoyed in the cosmopolitan atmospheres of Marrakesh, Cairo and Baghdad before the military coups. And contrary to popular belief, our ancestors carried no sickles or swords. From Sana’a jewelers to Iraqi clerks under British rule, Persian rug merchants and Marrakesh textile merchants, the majority of Mizrahi Jews lived in urban areas.

In Israel, Mizrahi Jews found a political rule that penetrated all aspects of civilian life, controlling and demanding full obedience even in matters like culture and music. Everyone had to conform to the idealized Sabra figure who sang “Hebrew” music – as in, Eastern European music with Mizrahi touches, celebrating the earth-tilling farmer and the hero soldier. The Broadcasting Authority’s Arab Orchestra, where only an small portion of the musicians were employed and paid meagerly, was established for the sole purpose of broadcasting propaganda to Arab audiences, never with a thought toward domestic consumption.

Patriotic songs that tried going Mizrahi weren’t of any greater appeal. We didn’t get what was so mizrahi about their monotonous drone. On rare occasions, a moving song like “Yafe Nof” slipped through. Written by Rabbi Yehuda Halevi and composed by the talented Yinon Ne’eman, a student of songwriter Sarah Levi Tanai, the song plays like an ancient Ladino tune, sung in Nechama Hendel’s beautiful, ringing voice. The delightful Hendel, who had also been shunned by the cultural establishment for a time, sings the magical Yiddish tune “El HaTsipor” (To the Bird), a diasporic soul tune that occasionally snuck its way on to the radio. At the time, I thought this song seemed more adequate in relation to the sorrows of Ashkenazi Holocaust survivors living in my neighborhood than what “Shualey Shimshon” (Samson’s Foxes) had to offer.

There were exceptions, such as Yosef Hadar’s timeless “Graceful Apple” and the internationally acclaimed “Evening of Roses.” Most of the several-dozen versions of this song circulating on the net were not posted by Israelis or Jews, but rather by music lovers in general.

By the early 60s even the founding fathers’ children began rejecting pioneer music, in part due to the rise of the urban bourgeoisie in Israel and its desire to break away from a self-imposed quarantine in exchange for a connection to the West. Naomi Shemer, Israel’s national songwriter, frequently borrowed from Georges Brassens’ chansons and from the Spanish songs of Paco Ibañez. The musical shortcomings of the Kibbutz-born composer are evident by the influences she heavily leaned on during the 60s. You can hear it not only in the tune she used for Israel’s national song, “Jerusalem of Gold,” taken from Paco Ibañez’ Basque folk song “Pello Joxepe“, but also in “On Silver Wings” – a patriotic song glorifying air force pilots. The prettiest phrase in the song (at 0:36) was taken from Brassens’ “La Mauvaise Reputation” (0:21). The irony lies in the fact that Brassens’ song was actually about a nonconformist who chooses to stay in bed on France’s Bastille Day – the entire song is a hymn of dissent.

Mizrahi youth were similarly stranded during the 60s. The radio played songs by artists who came from old Israeli-Sephardic families, such as the great Yossi Banai, who sang a captivating Brassens (translated by Shemer), Yoram Gaon in Ladino, and the Parvarim Duo. Although newer immigrants like Jo Amar managed to slip some heritage into the airwaves, the rest were facing a hopeless situation. They did not have the cultural freedom to delve into their family’s musical heritage and come up with something new of their own.

Zohar Levi To Zohar Argov

In order to escape the Cossacks and their horas, Mizrahi children – as well as the founders’ children – turned to Radio Ramallah, where they could catch up on the Western youth culture denounced by Israel’s cultural-political establishment. Elvis Presley, his voice heavily laced with black gospel, had a deep influence on Mizrahi youths. They would congregate, on the beach or during school breaks, clapping their hands to a rock n’ roll rhythm, usually carrying a small comb in their back pocket (next to a small color photo of The King) in order to arrange a brilliantine hairdo. They would bravely sing away senseless made-up rock n’ roll stand-in lyrics.

Ahuva Ozeri, of the same generation (seen here drumming in a home gathering in the 80s), does a delightful Mizrahi soul cover of Elvis (full of funny Yemenite curse words) and finishes it off with a Yemenite Mawal (01:18). Another possible marker of that generation is represented by an anonymous cover of Jail House Rock, sung in a heavy Moroccan accent. And then there is Shimi Tavori, performing a cover of The Beatles’ Don’t Let Me Down, after singing Farid al-Atrash’s “Ya Yuma” with singer Uri Hatuka chiming in (10:00).

Even when these artists did not remember all the lyrics, their groove and feel for the material was spot on, as if they were born on the Mississippi. Mizrahi and other laborers working in the industrial areas of Hamasger Street in Tel Aviv and in Ramla would return at night to the same streets to visit discotheques. Back then (and to this day) Mizrahi musicians had been equal participants in the nascent Israeli pop-rock scene. Here are the Churchills with lead singer Danny Shoshan playing a Beatles cover.

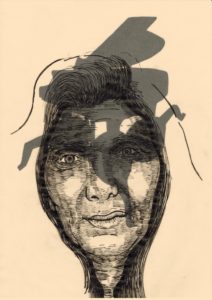

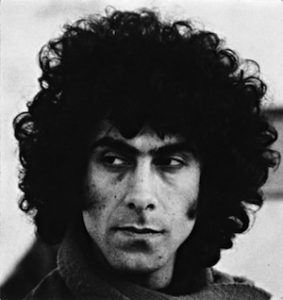

Drummer and composer Zohar Levi, a pioneer of Israeli rock music who composed the score for Hanoch Levin’s 1970 play “Queen of a Bathtub,” presents a possible musical turning point. Levi was also a founding member of Aharit Hayamim, a prominent band in Israel’s rock history. Here we see lead singer Gabby Shoshan performing the Levi-composed “Open the Door” with a touch of Mizrahi groove. Levi’s music has some “Hair” influence in it, along with a hint of Jefferson Airplane, but not much of Baghdad – the place where he was born.

When the founders’ children made haste to adopt a rebellious Western youth culture in the seventies, one might have expected the daring Levin to be the likely role model. The new music should have turned its back on the establishment’s preposterous musical dictums and its mentality of obedience. But talented artists such as Matti Caspi, Ariel Zilber (at the time) and Shalom Hanoch were not really aiming at instigating a “Zionist Spring”; they satisfied themselves with adopting rock techniques and rhythms, as well as the Israeli petite-bourgeois notion that everything taking place in Western capitals is best. The idea was to decorate Hebrew music with some pop-rock. This meant that Mizrahim like Zohar Levi were expected by peers to abandon their heritage in order to progress. Levi represents a shift from a music that grew out of a local and Arab cultural context to a mere imitation of the West, signifying yet another setback for Mizrahi musical culture in Israel. After all, composition is at the very heart of music making. At this point, defeat becomes apparent, as there is no real competition to authentic British and American Rock (even English-speaking countries like Canada and Australia failed miserably).

When comparing Zohar Levi to his Arab contemporaries, such as the younger Ziad al-Rahbani in Lebanon or Ilham al-Madfai in Iraq, the plight of this young Mizrahi generation becomes clearer. Rahbani – the composer, pianist, playwright and actor, had no problem integrating his musical heritage with the jazz and rock music that interested him. Here is his “Abu Ali,” written in 1972, roughly around the time when Zohar Levy was active. As for al-Madfai, he found no problem incorporating Flamenco into his Iraqi sound. Both Rahbani and al-Madfai play frequently in international venues. Levy’s Arab contemporaries showed him that in order to advance his art, there was no real need for him to set aside his heritage. On the contrary – he could have reached into it. In the end, Levy’s musical career was short lived, and despite his impressive talents he did not become the Israeli Rahbani. There were others who did manage such an integration further down the road, such as Yehuda Poliker and Shlomo Bar.

In fact, the new musicians of “Hebrew music” left the wagon of Israeli music stuck in the mud, rutted by its habitual selective deafness. The time was right to not only admire black music because the Beatles and Rolling Stones were making it, but also to try looking at the musical culture of oppressed people at home, which also included Yiddish music. To illustrate just how bad it was – the extent to which prominent Israeli artists were detached and myopic – I’ll mention how Matti Caspi, despite his great talent and musical erudition, disqualified Ofer Levy for choosing to sing in Arabic during an audition for a military band. Anyone who heard Levy singing a cappella back in those days would not be able to fathom such a decision. The story perfectly sums up the essence of the meeting between those generations: Ofer Levy gets Matti Caspi, but Matti Caspi is very much ignorant of Ofer Levy.

The “tape music” (“Kasetot”) that emerged in the late 60s was the sole propriety of Mizrahi Jews, and showed signs of integration with local music with pop-rock. The hafla (a common local ‘shindig’, or gathering) crowd played their own interpretations of Mizrahi and Zionist music, using rock as their medium. Since Mizrahi music was not being taught in Israeli schools, and studying it with musicians abroad seemed like a backwards thing to do, guitarist Yehuda Keisar would sneak into Aris San’s concerts to learn some of his electric guitar secrets. The pioneers of Kasetot music, many of whom were born to Yemenite families who settled in Israel generations ago, and whose sons were educated in kibbutzim and boarding schools, lost the ability to play classical Mizrahi and Western instruments (with the exception of Ahuva Ozeri who played the bulbul tarang, and Moshe Meshumar who played the mandolin). At the same time, Arab musicians of the same generation were still studying classical Mizrahi and Western instruments.

When examining the repertoire of Kasetot music, one finds that alongside the tremendous curiosity and openness it showed towards Mizrahi and Mediterranean styles (and even to that of Hasidic music), early adopters of the genre used many “Hebrew” songs, applying to them their own unique interpretations and rhythms. Back in the 90s, I created the TV series “A Sea of Tears,” which chronicled the history of Israel’s Kasetot music. In it, Ahuva Ozeri said she tried to “add some spice” to the songs, to make them more appealing to Mizrahi ears, or in other words, to serve as a link between Mizrahim and the established culture. Paradoxically, these musicians, who at last managed to make Zionist music more popular with Mizrahim, were the ones to put the cultural establishment in Israel into a blind panic.

At the peak of its success, you could see how the building blocks of Mizrahi music continued to crumble. This time in favor of borrowed music, mainly due to the sidelining of earlier generations of musicians, creating a gaping musical void. Composers of this new style were a small few, mostly without proper instrument training (apart from Ozeri). Ozeri, together with Avihu Medina and singer Avner Gaddasi, were not enough to supply the demand. Medina acknowledged several times that as a boy educated in a kibbutz, his role model had been Naomi Shemer, rather than composers like Aharon Amram or Saleh al-Kuwaiti, who lived in Tel Aviv’s Hatikva neighborhood and sold home appliances. True enough, you can hear the Hora rhythm at the beginning of every verse in “Kvar Avru Hashanim.” In fact, Kasetot music was the compromise second generation Mizrahim made in order to be accepted by the cultural political establishment and receive some airtime. Otherwise, their fate would have been as bitter as that of the artists described in part one of this series. But this compromise was not enough to appease the establishment, which continued to disregard and ridicule these artists for many years.

Kasetot music in those days suffered from poor production value. Studio musicians – a prerogative lavished on artists accepted by the establishment – had been too expensive for Kasetot singers to afford. It goes without saying that the quality of production served as one staple excuse to shun the music. The texts they used, one example of which is the lofty biblical Hebrew Medina learned at home, marked it as outsidermusic of the Mizrahi variety. If we compare it to the approachable feel-good vibes of his contemporaries in Kaveret (a band well-enough versed in local social codes to allow for that kind of verbal jugglery), we can imagine how Mizrahi Jews did not feel at home.

A visit to the Zemereshet website, the main source for Zionist songs, finds dozens of kosher Zionists songs performed by the Hafla crowd. Israel’s cultural commissars would never have dreamt it. It is interesting to note that the songs which captivated that crowd most were not songs of war songs nor marching songs, but rather sad romances. Here is Chen Carmi singing Alexander Penn’s “Suru Meni” to an unknown tune, and here is another interpretation by Rami Danoch of the Oud Band.

Kasetot music, with all its blemishes and delights, had become the only original genre to come out of Israel, and was in fact the most in sync with musical trends abroad: a pop music that successfully blended a mix of ethnic styles.

Sheltered By their fancies

Several years ago, Ariel Hirschfeld, a scholar of Israeli literature and culture, wrote an essay about the late composer Moshe Vilensky. Titled “The Rust of the Obvious,” the essay hails Vilensky as the greatest composer of Israeli music, urging readers to return to his music and to try and “remove the rust of the obvious” while listening again to his songs. Hirschfeld’s words clearly convey the distance between music that is obvious, and music that had ceased to be obvious.

YouTube makes it possible for us to observe how the Zionist founders and their children are sheltered by their fancies of fine tastes and beautiful melodies. It was generally believed that if they were not stuck in the Middle East, surely the whole world would have admired their music. But here they are, all the songs can be found on YouTube, and who listens to them apart from Israeli audiences? The answer is nearly no one. You won’t find any initiatives by foreigners on the web to upload “Hebrew Music.” Many of these songs have only several thousand views and comments strictly in Hebrew.

Even in videos from a later period, often referred to as “new Israeli music” – such as a highly esteemed song like “Atur Mitskhekh” – regarded in some media circles to be the foremost Israeli song of all times, sung by the captivating Arik Einstein and garnering over half a million views — all the comments are in Hebrew, apart from one curious passerby. The same song, uploaded to an English channel on Israel’s musical history, lingers at a mere 1,300 views. Even artists who were selected to represent Israel at the Eurovision song contest (back when a state-appointed the committee chose the competitiors), viewed by many millions in Europe, were not able to harness this exposure to success abroad. The case is the same with artists who were sent by the state on concert tours abroad. A 1974 video of the most admired band in Israeli rock, Kaveret, performing “Natati La Hayay,” posted on the Eurovision’s English-language YouTube channel, has less than 35,000 views. Kaveret’s “Baruch’s Boots” has less than 30,000 views and few comments, most of which are in Hebrew (except for several ones in English, posted by an American Jew who spent some time in Israel in the 70s). After the political power shift in 1977, Mizrahi musicians were chosen by the public to represent Israel in the Eurovision. Yizhar Cohen won the contest in 1978, with hundreds of thousands of views from non-Israeli viewers to show for it. Dana International achieved similar results.

Even Shlomo Artzi, who was sent to the contest in 1975 with “At Va’Ani,” has had very few of his songs uploaded by non-Israelis (apart from “Iceland,” performed in Hebrew by the Jewish French singer and actor Patrick Bruel on French television, with some 120,000 views). Artzi also has few uploads on Spanish or English channels, and not many views. His song “Wiping Your Tears,” on his official channel, has 1.6 million views with comments made only by Israelis (including one Arab Israeli). A version of this song uploaded with an English title to a channel dedicated to old Hebrew songs has only 26,000 views.

Compare this to the oeuvres of the great Jewish-American composers, Irving Berlin, George Gershwin and the likes of Benny Goodman, who readily absorbed everything they could lay their hands on in their new homeland – particularly the music of the oppressed African Americans – and allowed their music to express universal concerns of human existence, and you might begin to understand how the sons of our conservative revolutionary movement did not get very far with their cultural narrow-mindedness and ideological zeal.

It seems that the destitute of Israel’s music scene are the ones chosen by global Internet citizenry to advance to the front of the stage. Ofra Haza, for instance, could not get any composer of “Hebrew” music to work with her until the late 70s. Here she is singing “Im Nin’elu” together with the Hatikva Neighborhood Workshop Theater in the early 70s, in a program produced by Israel’s national Channel 1. The YouTube clip for this Yemenite song, composed by Aharon Amram, has more than 2.2 million views. Finely arranged by Yigal Hared, the song remains close in spirit to the original. The cultural crudeness of the establishment makes an appearance one minute into the song, when program director Rina Hararit queues the ending credits to run over Haza’s face. This clip has more than 3,200 excited comments, the great majority of which are not by Israelis. The version by the Hatikva Workshop Theater has more views than the remix version that would go on to propel Haza to worldwide stardom in the mid-80s. Apparently some felt the song did not need electroshock.

Some may say that Haza is famous enough, such that anything of hers will receive many views. But that is not so: her “songs for the homeland” have a much smaller audience. Here is Naomi Shemer’s “Renewal,” with only 9,000 views, or Ehud Manor and Nurit Hirsch’s “Every Day in the Year” with 23,000. The more Haza distanced herself from songs of earth-toiling and pop towards the end of her life, the more her confidence in her musical depth grew and the more she matured. Here she is performing at the Monterey Jazz Festival, singing a “Kadish” composed by herself and Bezalel Aloni. The clip has over a million views, most of the comments are not in Hebrew, by non-Israelis (judging by the comments, most are probably not even by Jews). Even a stone would be moved by it. Here is another lovely example of an Aharon Amram composition: Shirley Zapari, her mother Miriam Zapari and Achinoam Nini singing “Tsur Manti,” recorded from the Mezzo channel by an Israeli – over 1.2 million views. Amram’s song has double and triple the views of other Nini songs, such as the theme song for Roberto Benigni’s “La Vita è Bella” or her “Ave Maria.” Both were uploaded by non-Israelis.

There is yet another destitute Israeli musical genre that is very popular on the Internet – Hassidic klezmer music. Here is virtuoso violinist Itzhak Perlman with a Klezmer band from the U.S., receiving high ratings for their exquisite playing and garnering more than 1.3 million views. Look hard, and you might find one Hebrew comment among the thousand. But not only the great Perlman gets attention – other anonymous Klezmers are not doing so bad on their own. Listen to gripping Russian Jewish music made by Reb Shaya. Judging by the comments, most of the half-million ecstatic viewers are neither Israeli nor Jewish. The stale Israeli argument that every rejection of Israeli artistic offerings is motivated by anti-Semitism is somewhat hampered by these findings. Perhaps we would do better to consider an alternative conclusion, one that would better enlighten the connection between a military existence, a cultural enclave mentality of nationalistic ideological zeal, and artistic ineptitude.

—

This post originally appeared in Hebrew on Haokets. Translated from Hebrew by Yoav Kleinfeld

Part One: http://rozenbergquarterly.com/riches-to-rags-ingers/

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply