Speaking Papiamentu ~ On Re-Connecting To My Native Tongue

03-07-2024 ~ It starts at Schiphol, the Amsterdam airport. Before that, I am still immersed in my life in Jerusalem, busy with family matters and with grassroots activism against the Israeli occupation, while under pressure to finish grant proposals for the multicultural Jerusalem feminist center and art gallery where I work. I do not have time to connect emotionally to my trip, which still feels more like a yearly obligation to visit my elderly mother in Curaçao, when I would rather spend my precious vacation time trekking in Turkey or Nepal.

03-07-2024 ~ It starts at Schiphol, the Amsterdam airport. Before that, I am still immersed in my life in Jerusalem, busy with family matters and with grassroots activism against the Israeli occupation, while under pressure to finish grant proposals for the multicultural Jerusalem feminist center and art gallery where I work. I do not have time to connect emotionally to my trip, which still feels more like a yearly obligation to visit my elderly mother in Curaçao, when I would rather spend my precious vacation time trekking in Turkey or Nepal.

I usually have a few hours to kill, not enough to take the train into Amsterdam and visit old friends, which I do on my return trip when I have almost twelve hours between planes. And so, I silently wander around the airport, feeling a little like a spy, as I do in Jerusalem when I hear Dutch tourists speaking on the street, not suspecting that I, who probably look like a local to them, would understand. Not identifying myself as a speaker of Dutch, I take in the talk, smiling to myself, my little secret.

Here, in transit at the airport – a liminal space par excellence – I sometimes pretend to be a total stranger and address the salesperson in English. Perhaps that has more to do with the fact that I have not yet woken up my slumbering Dutch, or do not want to give away my unfamiliarity with the currency and other taken-for-granted facts of daily life in the Netherlands.

Or perhaps it is my resistance to being taken for an “allochtoon” – that polite way they refer to the “not really Dutch,” who nevertheless hold Dutch citizenship – a category that groups together the mostly Moslem migrants and those of us, from the former Dutch colonies, blacks and whites alike. It is a label that had not yet been coined when my schoolteachers in Curaçao taught us to see Holland as our “mother country,” to sing Wilhelmus Van Nassauwe, the Dutch national anthem, on Queen Juliana’s birthday and to accept the Batavians, a Germanic tribe, as “our” ancestors. They say that when you count, you invariably give away your mother tongue – to this day I count not in Papiamentu, but in Dutch, so totally did I embrace the colonial language.

I was four when I learned Dutch in kindergarten. I remember the feeling of utter embarrassment when everyone expected me to speak Dutch with my cousins whose father was Dutch, and I ran away crying. I was losing the secure ground that Papiamentu provided, having to jump into the deep waters of a foreign language without a life-vest before I knew how to swim.

Very soon, however, I was speaking Dutch fluently, determined to excel in the language. I wanted to know it even better than the Dutch children whose parents came from Holland. I spoke Dutch with all my school friends, even though most of us spoke Papiamentu at home, including the handful of schoolmates from my own community, the Sephardic Jews who settled on the island in the seventeenth century, after fleeing the inquisition in Portugal and Spain.

In my elementary school days, the teachers forbade us to speak Papiamentu even in the schoolyard, claiming it was the only way to learn proper Dutch. And so, I read, wrote, and thought in Dutch – it became my first literary language, as Papiamentu was basically only a spoken language at that time. Now, as I write this in 2007, after forty-two years away from the Dutch speaking world, my Dutch gets rusty, until I find myself again surrounded by its sounds and it returns to me and becomes almost natural.

I roam around the halls of the airport’s immense shopping center, not quite knowing what I am looking for. It is rather busy at the camera counter – I realize it is not a place to come with all my questions about which new camera to buy, my first digital SLR, after getting excited with the results of my digital point and shoot. Up to now, I had refrained from following the footsteps of all the other photographers in my family and never took my photography seriously. All that changed when I realized that editing my digital photos could finally give me the control over my images that I sought.

No, there is no point shopping here, I’d better look at cameras in Curaçao at a more relaxed pace, where the prices will certainly be lower. At least they used to be, when I was growing up and the island was still a duty-free paradise for American tourists.

Suddenly I remember that once, in these huge avenues of shops designed to entice travelers on the move, there used to be a stand with fresh, raw herring. I do not see it anymore, even though this is still the season of the celebrated first herring catch – the end of June. It fills me with longing, even though “new” herring was not something we ate at my home, it is what the “real Dutch” loved. Raw herring is a taste I developed later, and yet, it is so very much a taste from that past, perhaps from my acquired Dutch identity, and I feel that eating herring now would prepare me for my return. Read more

Gerrit Boer – Diggels. Op vesite in de Veenakker. Naogedachten.

Gisteravond was ik al lezend een paar uur in de Altingerhof in Beilen. Op de afdeling voor dementerenden, de Veenakker, woonde de opoe van Gerrit Boer.

Gisteravond was ik al lezend een paar uur in de Altingerhof in Beilen. Op de afdeling voor dementerenden, de Veenakker, woonde de opoe van Gerrit Boer.

Boer heeft met ‘Diggels. Op vesite in de Veenakker. Naogedachten’ een ontroerend boek geschreven over de bezoeken aan zijn oma in de voorbije jaren.

‘Diggels bint weergaves van woorden en bielden die mij bijbleven bint nao jaorenlange vesites in de Veenakker, verpleeghuus in Beilen veur mèensen met dementie. Vesite betiekent: theedrinken en meelkoekjes eten met de woongroep van opoe, kuiern met zien beiden.

Diggels bint naogedachten over een leven in Midden-Drenthe, vertellings over’t dörp, verhalen over de ruilverkaveling, over de moestuun, over törf, over bloempies, over vögels, over ‘t Olde Diepie, over stienen en over dingen die west bint. Zaken die eigenlijk al vergeten bint en toch iniens weer opduukt.

Totdat alles vort is.

Herinnering is seins een singeliere kostganger.’

Het is verleidelijk om aan de hand van citaten te laten zien hoe langzaam, maar onomkeerbaar, opoe verdwaalt in haar eigen wereld. En hoe mooi het Drents is.

Eentje dan:

‘s Aovends nao ’t melken was ’t eten en koffiedrinken. Miesttied las Harm de Asserkraante en ik dee ok wat. Breien, of ik schreef wat op’n bladtie pepier. Op de achterkaante van een kelenderblad of zukswat.

Seins zungen wij ook wal. Harm speulde mondharpie en ik zung. Daar bij die molen of Achter in het stille klooster …

Dat is wal droevig, dat liedtie, moar wij kunden wal mooi zingen met zien beidend.

Het boek is meer dan ‘wal mooi’.

Wat een bijzonder boek.

Gerrit Boer – Diggels. Op vesite in de Veenakker. Naogedachten.

Uitgegeven door Stichting Het Drentse Boek.

ISBN 978 90 6509 272 4

Bestel het boek in de boekhandel of rechtstreek: https://huusvandetaol.nl/…/diggels-op-vesite-in-de…/

Wat kost dit boek?

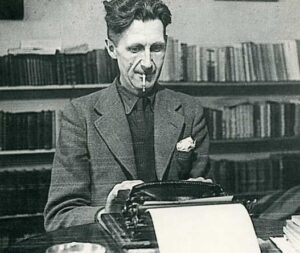

George Orwell – die toen nog gewoon Eric Blair heette, het was ver voor de verschijning van Animal Farm en 1984 – werkte in 1934 en 1935 enige tijd in een boekwinkel met tweedehands boeken, tevens buurtbibliotheek. Booklover’s Corner heette de winkel, gevestigd op de hoek van South End Green in de wijk Hampstead in Londen.

Boekverkoper had Blair een ideaal beroep geleken: je verbleef de hele dag tussen boeiende literatuur, er kwamen vast en zeker interessante klanten die je kon voorzien van deskundig advies. Het viel hem vies tegen.

Ergernissen

Niet het assortiment viel hem tegen – dat was zeker aantrekkelijk – maar vooral de klanten vormden voor hem een bron van ergernis. In zijn essay Bookshop Memories vatte hij dat ongenoegen later samen: “Many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a nuisance anywhere but have special opportunities in a bookshop. For example, the dear old lady who ‘wants a book for an invalid’ (a very common demand, that), and the other old lady who read such a nice book in 1897 and wonders wether you can find her a copy. Unfortunately she doesn’t remember the title or the author’s name or what the book was about, but she does remember that it had a red cover.”(1)

Daarnaast doemden vaak figuren op, net ontstegen aan de zelfkant der samenleving, die een poging deden de handelaar waardeloze boeken te verkopen, of de types die voortdurend boeken lieten reserveren, maar niet de intentie hadden deze ooit op te halen of te betalen. En dan waren er nog de klanten die gefixeerd waren op één onderwerp en voor wie de rest van geen belang leek. Echte boekenliefhebbers, -kenners of verzamelaars leken maar een klein deel van het klantenpotentieel uit te maken. Het lijkt een probleem van alle tijden.

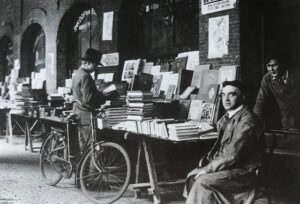

Boekenmarkten

Uit eigen ervaring – op tweedehands boekenmarkten in Deventer, Dordrecht en langs de Amstel – ken ik het verschijnsel. Menig handelaar herkent de klanten die nog tijdens het etaleren van de boeken op de kraam, ongevraagd je dozen openmaken en alvast de handel inspecteren. Of de op iedere boekenmarkt opduikende vader en zoon die vanaf het middenpad de handelaar toeroepen: ‘Heeft u ook olifantenboeken?’ In het kielzog vaak gevolgd door het oudere echtpaar met boodschappentrolley, vanaf dezelfde plek ‘Hallo!!’ naar de handelaar roepen, en vervolgens een bordje met het woord Bridge omhoog houden, toegelicht met de vraag: ‘Heeft u ook boeken over bridge?’ En wat te denken van de klant die in een pittig tempo komt aangelopen, het eerste de beste boek op de kraam aanwijst met de vraag ‘Wat kost dit boek?’ En na het antwoord – 12,50 – zegt ‘Dan weet ik genoeg! Bedankt!’ in hetzelfde tempo doorloopt.

Vergane glorie

Vergane glorie

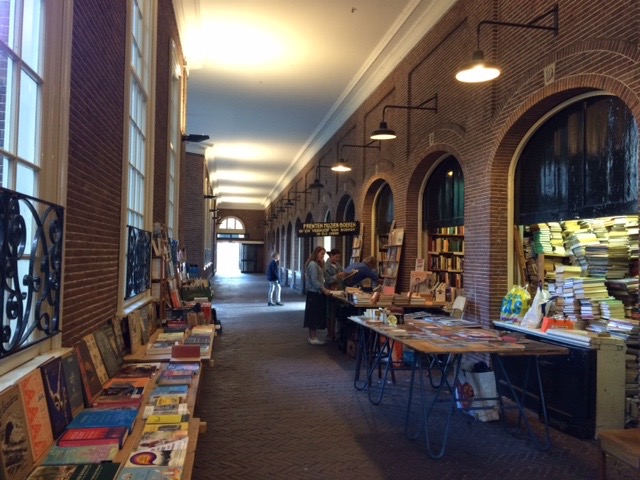

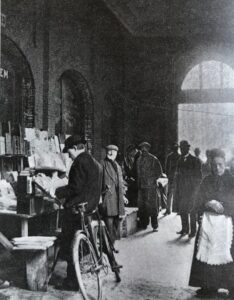

Het zijn voorbeelden van kopersgedrag wat boekhandelaren in de Amsterdamse Oudemanhuispoort in de jaren zeventig van de vorige eeuw al herkenden. ‘Oudemanhuispoort is echt vergane glorie’, zo kopte de NRC in een artikel uit 1974, waarin boekhandelaar Chris Smit tegen journaliste Lisette Lewin mag mopperen over de goede en slechte tijden van deze historische plek.(2) Hij klaagt over het gebrek aan interesse voor ‘het betere boek’.

En de studenten dan? Lezen die niet meer? De oudere handelaar in de Poort die ik onlangs sprak schetst een weinig gunstig beeld van het koperspubliek. ‘Studenten die hier door de Poort lopen, kijken alleen maar op hun telefoon’, zegt hij. ‘Voor boeken hebben ze geen belangstelling.’ Het gaat niet goed met de handel zo blijkt. Corona bracht de handel nog eens een extra slag toe. ‘Helaas moeten we het voor een groot deel hebben van toeristen, maar die zijn er nu niet. Ik moet het hebben van gepensioneerde Engelse echtparen en dat soort volk. Rozenkwekers, bijenhouders en zo, en echte liefhebbers en verzamelaars op zoek naar een gespecialiseerd boek. Of mensen die als souvenir uit Amsterdam een mooi boek willen meenemen.’

Schuifdeuren

De Poort is niet altijd een aangename plek om boeken te verkopen, zo verzekeren de handelaren. De schuifdeuren die enkele jaren geleden aan beide zijden van de gang zijn geplaatst nemen gelukkig nu veel van de tocht en kou weg, maar van prettig in de zon zitten is er hier nooit sprake en het blijft vaak kleumen. Dat de handelaren dus niet iedere dag aanwezig zijn en hun aanwezigheid laten afhangen van de weersomstandigheden, moet de koper maar voor lief nemen.

Winkelkasten

Winkelkasten

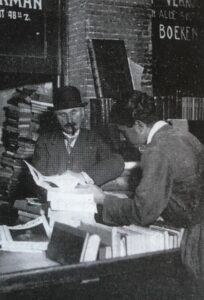

Generaties boekverkopers hebben sinds 1876 via de Universiteit van Amsterdam de beschikking over een boekenstal in de Poort. Daarvoor stonden de handelaren op een vaste boekenmarkt op het Rembrandtplein, maar toen daar het beeld van de schilder geplaatst ging worden, moesten de handelaren verkassen. Er was ruimte in veertien zogenaamde winkelkasten in de Oudemanhuispoort, plekken die daarvoor waren gebruikt door handelaren in goud, zilver en sieraden.(3)

Onbekende brieven

Op een bepaald moment in de jaren tachtig leek even een bijzondere vondst in de Oudemanhuispoort een belangrijke voetnoot op te leveren bij de levensbeschrijving van een Nederlandse premier. Igor Cornelissen (1935-2021), destijds redacteur bij het weekblad Vrij Nederland, was vrijwel dagelijks een bezoeker van de boekenkasten in de Oudemanhuispoort.

De meeste handelaren kende hij goed. In de Poort kwam hem een gerucht ter ore over vooroorlogse onbekende brieven van minister-president Colijn aan diens geheime Duitse minnares. De brieven zouden al eens in de Poort zijn opgedoken, misschien wel verhandeld.

Zouden ze nog te vinden zijn? De inhoud zou bij publicatie ongetwijfeld een heel ander beeld hebben opgeleverd van de stugge, uiterst conservatieve houwdegen Colijn.

Helaas bleven de brieven voor Cornelissen onvindbaar. Nadat hij in Vrij Nederland over de mogelijke minnares had geschreven, moest de biograaf van Colijn – die het bestaan van de minnares fel had ontkend – tandenknarsend toegeven dat het verhaal over de minnares op waarheid berustte.

Tijdsbeeld

Tijdsbeeld

Het gerucht vond verder zijn weg in de roman De brieven van Colijn (1988) van Cornelissen.

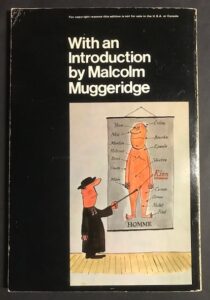

Het eerste hoofdstuk geeft bovendien een mooi tijdsbeeld van de Poort. ‘Er hing een penetrante pislucht in de Oudemanhuispoort’, is de openingszin van de roman. En: ‘Kwam het door de honden, of waren het mannen geweest die zich de vorige avond in de Staalstraat met bier vol hadden laten lopen en, op weg naar het Spui, hier kletterend hun blaas hadden geleegd?’ (4) Het waren ook de jaren waarin junks voor een relatief aangename slaapplek hun toevlucht zochten tot de Poort. Geen prettig gezelschap wanneer je serieus naar boeken speurt. Toch was de Poort voor Cornelissen een bijzondere plek. Hij bleef er tot aan het eind van zijn leven vaak komen. Ooit had hij zich voorgenomen eerste drukken van de boeken van George Orwell te verzamelen. Tijdens reizen naar Engeland bleek hem echter dat deze onbetaalbaar waren. Een eerste druk Orwell – mogelijk door een handelaar niet als zodanig herkend – trof hij in de Oudemanhuispoort nooit aan.(5)

Kennis en deskundigheid

De kans op een dergelijke vondst moet ook vrijwel nihil worden geacht. Immers, de kennis van handelaren over titels, uitgevers, een zoveelste druk of omslagontwerpers moet niet worden onderschat en wordt vaak geroemd. Tegenwoordig is de vraagprijs van een titel op internet makkelijk na te gaan. Maar voor de oorlog al stonden Poorthandelaren als Barend Boekman (1869-1942) en de gebroeders Van Kollem bekend om hun brede kennis van zaken en deskundigheid. Vaak wisten zij precies wat ze in huis hadden, ze kenden hun klanten en wisten waar de belangstelling naar uit ging en welke prijs ze konden vragen. Handelaar Chris Smit was actief in socialistische kringen en had een enorme kennis van boeken en brochures over het socialisme, communisme en anarchisme. Wie een bepaalde obscure socialistische brochure uit het interbellum zocht, kon bij hem proberen.

Verzamelen

Maar is het als handelaar verstandig te handelen in een onderwerp waarin je zelf bent geïnteresseerd? Jaren geleden zocht ik de gepensioneerde antiquaar Gé Nabrink (1903-1993) op in zijn woning in Amstelveen. Voor de oorlog was Nabrink actief als anarchistisch en antimilitaristisch propagandist. Zijn antiquariaat in de Korte Korsjespoortsteeg in Amsterdam specialiseerde zich in boeken over Nederlands-Indië en Indonesië. Zelf verzamelde hij boeken en brochures over het anarchisme. ‘Maar daar ga ik niet in handelen’, zo verzekerde hij me.

‘Dan ondergraaf ik mijn eigen collectie en dan heb ik later spijt van wat ik verkocht heb.’

George Orwell verzamelde geen boeken. Na zijn baantje als boekverkoper stopte hij met het kopen van boeken. Het werk in Booklover’s Corner had hem voorgoed daarvan genezen.

Alleen als hij een bepaald boek niet kon lenen, wilde hij het nog wel eens aanschaffen. Niet alleen stond de weeë geur van oud papier hem tegen, maar ’In gedachten associeer ik het vooral met paranoïde klanten en dode kwallen.’

Noten

1. Bookshop Memories verscheen in november 1936 in het tijdschrift Fortnightly. Het werd herdrukt in: George Orwell, The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume 1, An Age Like This 1920-1940, Penguin Books 1970

2. Lisette Lewin, Oudemanhuispoort is echt vergane glorie, in NRC Handelsblad, 8 januari 1974

3. De geschiedenis van de universiteitsgebouwen rond de Oudemanhuispoort, en een historische schets van de boekenverkoop in de Poort, is te vinden in: Jurjen Vis, De Poort. De Oudemanhuispoort en haar gebruikers 1602-2002, Boom, Amsterdam 2002

4. Igor Cornelissen, De brieven van Colijn, Van Gennep, Amsterdam 1988. (Is dat handelaar Max van Til daar op de omslagfoto van het boek?)

5. Over het verzamelen van boeken van George Orwell schreef Cornelissen o.a. in het laatste deel van zijn memoires Mijn opa rookte ook een pijp, Just Publishers, 2020. Cornelissens collectie Orwell wordt aangeboden door het door hem opgerichte antiquariaat ’t Wasdom in Zwolle.

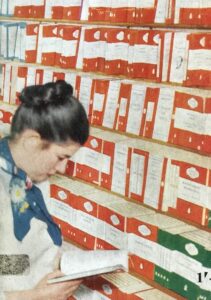

‘The Penguins are coming!’

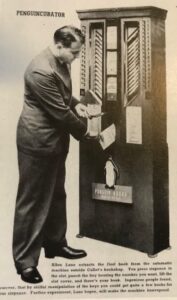

Volgens de gangbare legende ontstond het idee voor de bekende Penguin pockets bij de stationskiosk op het station van Exeter, in zuidwest Engeland. Allen Lane, redacteur bij de vermaarde uitgeverij The Bodley Head, wilde daar op een avond in 1935 de trein naar Londen nemen, na een logeerweekend in Devon te hebben doorgebracht bij detectiveschrijfster Agatha Christie en haar man, de archeoloog Max Mallowan. Hij verbaasde hij zich erover dat in de stationskiosk geen goedkope goede boeken te koop waren, in een voor een reiziger handzaam formaat, makkelijk mee te nemen dus, in de jaszak of reistas. Hij verwonderde zich ook over de abominabele inhoud van de aangeboden titels en de oppervlakkigheid van de genres in het assortiment. Ter plekke moet Lane bedacht hebben dat de markt rijp was voor het uitgeven van een serie voor iedereen betaalbare boeken in een handig formaat, die zich qua inhoud konden meten met de uitgaven van gevestigde Britse uitgeverijen. Literatuur, biografieën, poëzie, wetenschap en kunst, niet duurder dan de aanschaf van een pakje sigaretten.

Volgens de gangbare legende ontstond het idee voor de bekende Penguin pockets bij de stationskiosk op het station van Exeter, in zuidwest Engeland. Allen Lane, redacteur bij de vermaarde uitgeverij The Bodley Head, wilde daar op een avond in 1935 de trein naar Londen nemen, na een logeerweekend in Devon te hebben doorgebracht bij detectiveschrijfster Agatha Christie en haar man, de archeoloog Max Mallowan. Hij verbaasde hij zich erover dat in de stationskiosk geen goedkope goede boeken te koop waren, in een voor een reiziger handzaam formaat, makkelijk mee te nemen dus, in de jaszak of reistas. Hij verwonderde zich ook over de abominabele inhoud van de aangeboden titels en de oppervlakkigheid van de genres in het assortiment. Ter plekke moet Lane bedacht hebben dat de markt rijp was voor het uitgeven van een serie voor iedereen betaalbare boeken in een handig formaat, die zich qua inhoud konden meten met de uitgaven van gevestigde Britse uitgeverijen. Literatuur, biografieën, poëzie, wetenschap en kunst, niet duurder dan de aanschaf van een pakje sigaretten.

Uitgevers

Uitgevers

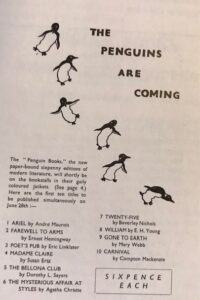

Datzelfde jaar nog verschenen de eerste tien Penguin pockets. Het waren herdrukken, gedeeltelijk afkomstig uit het fonds van The Bodley Head. De overige titels waren met enige moeite betrokken van andere uitgeverijen. Zes romans, een autobiografie, een biografie en twee crimenovels vormden de eerste tien. De uitgaven waren voor Lane een groot risico.

Mogelijk waren boekhandelaren immers niet geïnteresseerd in de uitgaven. En wat als uitgevers niet bereid waren titels uit hun fonds te leveren voor de Penguins? Boekhandelaren stonden dan ook in eerste instantie terughoudend of zelfs afwijzend tegenover de Penguins – de pockets zouden de verkoop van duurdere gebonden boeken in de weg staan – maar nadat warenhuisketen Woolworth in één keer een order van 63.500 exemplaren had geplaatst, was het succes voor Lane verzekerd. Hij nam ontslag bij The Bodley Head en vestigde Penguin als zelfstandige uitgeverij.

Penguins waren overigens niet de eerste pockets op de boekenmarkt. De Duitse uitgeverij Albatross bracht al jaren pockets op de markt, maar niet gericht op het grote publiek. Lane nam niet alleen het concept gedeeltelijk over, voor de naam van zijn uitgeverij koos hij gewoon een andere vogel.

Kleuren

Kleuren

Het omslagontwerp voor de pockets was simpel. Geen illustratie maar de auteursnaam en de titel op een wit vlak in het midden, en een gekleurde band boven en onder: blauw voor biografieën, oranje voor literatuur en romans, groen voor ‘Mystery & Crime’, later aangevuld met paars voor ‘Travel & Adventure’, geel voor essays en grijs voor aan actualiteit gelieerde titels.

Op ieder omslag prijkte een getekende pinguïn als logo. Edward Young, een jonge kantoorklerk op de uitgeverij, was naar de dierentuin in Londen gestuurd om pinguïns te tekenen. ‘My God, how those birds stink!’, zei hij toen hij met zijn schetsboek op kantoor terugkeerde. Penguin pocket no.1 was Ariel van André Maurois, een biografie van Percy Shelley. De duizendste Penguin verscheen op 30 juli 1954.

Puffins en Specials

Onder de reclameslogan ‘The Penguins are coming’ verschenen de Penguins daarop in rap tempo, eerst alleen herdrukken van eerder verschenen titels, maar met het stijgen van populariteit van de uitgaven, stonden auteurs te dringen om hun werk als Penguin te zien verschijnen.

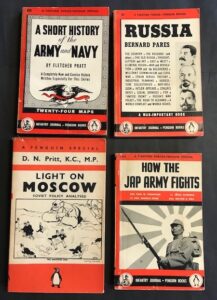

Lane wilde met het fonds een zo breed mogelijke markt bereiken. Voor wetenschappelijke en historische onderwerpen werd de aparte reeks Pelican pockets in het leven geroepen. Kinder- en jeugdtitels verschenen als Puffin Books, er kwam een speciale Penguin Shakespeare reeks,en reeksen met bladmuziek, toneel en poëzie. Vlak voor en tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog kon naar de vraag naar actuele onderwerpen worden voorzien door de Penguin Specials – Germany Puts the Clock Back, van Edgar Mowrer was in 1937 de eerste titel – en nadat in de Verenigde Staten Penguin USA was gestart, de Fighting Forces-Penguin Specials.

Verzamelen

Verzamelen

Wereldwijd zijn er duizenden verzamelaars van Penguin pockets. Het zijn niet de hedendaagse uigaven die door deze verzamelaars worden gezocht, maar juist de uitgaven die verschenen vanaf de oprichting van Penguin Books tot pakweg het einde van de jaren zestig.

Verzamelaars speuren naar de oorspronkelijke uitgaven met de gekleurde banden, of naar deeltjes van de speciale reeksen, of naar pockets met baanbrekende of gedurfde omslagontwerpen uit de jaren zestig. Sommige verzamelaars richten zich op eerste drukken, anderen proberen de eerste duizend of tweeduizend titels compleet te krijgen. Weer anderen verzamelen alleen Pelicans of boeken met de omslagen van een bepaalde ontwerper of titels van inmiddels opgeheven reeksen.

In de jaren zeventig werden de Penguins pas echt een massaproduct, voor zover ze dat al niet waren. Met de stijgende oplages leek de tijd van de gedurfde omslagontwerpen voorbij. De uitgeverij gedroeg zich steeds meer als iedere andere pocketuitgeverij in de strijd om de verovering van de pocketmarkt en leek zich steeds meer te willen stabiliseren en etaleren als een degelijke, betrouwbare uitgeverij met befaamde auteurs. Daarbij was voor experimenten in uitgeven en vormgeving steeds minder plaats. Vooral bestaanszekerheid en het vasthouden van het marktaandeel leken de aandachtspunten te zijn geworden.

Genootschap

Genootschap

De Penguin Collectors Society in Engeland, een genootschap van Penguin verzamelaars met ruim vijfhonderd leden, geeft een interessant tijdschrift uit, de Penguin Collector, waarin diverse facetten uit de historie van de uitgeverij worden behandeld. Er is aandacht voor zaken als de ontwerpen en belettering van uitgaven, de omslagontwerpers, curieuze drukken en gespecialiseerde reeksen van de uitgeverij. Aparte uitgaven verschenen over de vormgeving van Pelican Pockets, de omslagontwerpen van de Penguin Maigrets en over advertenties die in de oorlogsjaren in Penguins verschenen.

Op een willekeurige boekenmarkt kun je voor enkele euro’s meestal wel Penguin pockets aantreffen. Uitgaven die verschenen in lage oplages zijn natuurlijk zeldzamer. Verzamelaars zijn bereid daar meer voor neer te tellen. Maar wat is de meest gezochte Penguin pocket? En wat is de meest waardevolle Penguin? Maar is die meest gezochte ook de meest waardevolle?

Gezochte titels

In een recent filmpje op Youtube geeft verzamelaar Jules Burt een lijstje van de tien meest gezochte titels, met het bedrag wat er onlangs door verzamelaars op veilingen voor is betaald.

Het zijn allemaal titels van voor en tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, een tijd waarin de papierkwaliteit slecht was en de oplages relatief laag waren. Dat veel exemplaren die periode dan ook niet hebben overleefd is niet verwonderlijk. Zo verscheen het detectiveverhaal The Second Shot van Anthony Berkeley in een oplage van slechts 25.000 exemplaren. Een recente verkoop van die titel bracht driehonderd pond op. De roman Full House van M.J. Farrell is zeer gezocht omdat er maar één druk van de persen rolde. Een exemplaar ging onlangs voor vijfhonderd pond over de toonbank. Minstens even gewild is Biggles Flies Again van W.E. Johns, weliswaar een jeugdboek maar uitgebracht als ‘volwassen’ Penguin. Vijfhonderd pond werd er niet lang geleden voor een exemplaar betaald. Verzamelaar Burt noemt als meest gezochte en meest waardevolle titel Ariel van André Maurois. Maar het opvoeren van deze titel in dit lijstje lijkt me niet correct. Burt doelt namelijk op een advance copy – geen publieksuitgave – die door Lane werd gebruikt om aan boekhandelaren te tonen om interesse voor de pockets te wekken.

Er zijn hooguit tien exemplaren van gemaakt, met groene banden. Het is daarom niet vergelijkbaar met de overige gezochte titels. Er zijn maar drie exemplaren bekend, Penguin heeft het zelf niet in haar archief en ook het British Museum heeft het niet in haar collectie.

Later verscheen Ariel weliswaar als Penguin no.1, met blauwe banden, maar dat boek is met enig zoekwerk moeiteloos te vinden.

Cartoonist

Cartoonist

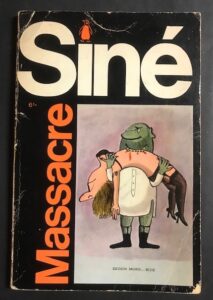

Aanzienlijk minder waard maar zeker gezocht is een boekje wat door andere verzamelaars wordt genoemd: Massacre van de Franse cartoonist Siné uit 1966. Op de antiquarensite Abebooks worden er bedragen tussen de tachtig tot honderd pond voor gevraagd. Lang niet zo waardevol dus, maar wel het boekje met het mooiste achtergrondverhaal.

Siné, pseudoniem van Maurice Sinet (1928-2016), tekende in de jaren zestig al venijnige, satirische cartoons voor het weekblad L’Express. Zijn anarchistisch getinte werk richtte zich vooral tegen het kolonialisme, het kapitalisme en de kerk. In 1981 ging hij tekenen voor het satirische weekblad Charlie Hebdo. Met een column over de zoon van president Sarkozy ging hij echter te ver, zo vond de redactie van Charlie Hebdo en zette hem in 2008 op straat. Men betichtte hem van antisemitisme. Siné richtte daarop zijn eigen weekblad op, Siné Hebdo.

Godslasterlijk

Godslasterlijk

Wereldschokkend zijn de cartoons in Massacre vandaag de dag nauwelijks te noemen, maar destijds werden ze door sommigen als controversieel en schokkend ervaren. Binnen de raad van bestuur van Penguin ontstond verschil van mening over publicatie. Lane stuurde de cartoons ter beoordeling naar een toonaangevende redacteur van de Times Literary Supplement, die ze ‘rather good’ vond. Lane zelf vond ze echter misselijkmakend. Na publicatie kwamen vanuit kerkelijke kringen kwamen felle protesten. Godslasterlijk en pornografisch, zo beoordeelden kerkelijke autoriteiten. Ook boekhandelaren protesteerden en stuurden exemplaren retour. In de raad van bestuur liep de affaire tussen voor- en tegenstanders van verspreiding hoog op. Woedend reed Lane daarop op een avond naar de Penguin vestiging in Harmondsworth, laadde de exemplaren van Massacre uit het magazijn in een busje en reed ermee naar zijn boerderij. In de tuin wierp hij de boeken op een hoop en stak er de brand in. Volgens andere bronnen begroef hij de exemplaren in zijn tuin. De exemplaren zijn in ieder geval nooit meer tevoorschijn gekomen.

De volgende ochtend vond een medewerker nog 220 exemplaren op het Penguin kantoor, die Lane vergeten was. Deze en de retourexemplaren gingen de kluis in. Vanaf dat moment gold voor het boekje ‘out of print.’

Literatuur:

– Phil Baines: Penguin by Design. A Cover Story 1935-2005, Allen Lane-Penguin Books 2005

– Jeremy Lewis: Penguin Special. The Life and Times of Allen Lane, Penguin Books 2006

Wat is lang? Een onderzoek naar lange filmtitels

Ach, wat is lang? Dat is relatief.

Ach, wat is lang? Dat is relatief.

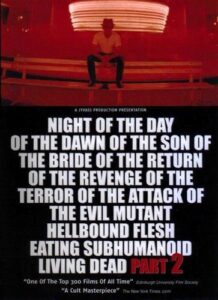

Night of the day of the dawn of the son of the bride of the return of the revenge of the terror of the attack of the evil, mutant, crawling, alien, flesh-eating, hellbound, subhumanoid , zombiefied living dead part 2: in shocking 2-D (2011), bijvoorbeeld, wordt met zijn 40 woorden in vakkringen beschouwd als langste filmtitel.

Het is een parodie op The night of the living dead (1968), de titel van de film waarmee George A. Romero zijn regiedebuut maakte met een budget van slechts $ 150.000,-, een film die nog altijd een van de best gewaardeerde griezelfilms is.

De grap is dat in die ellenlange titel de namen van tal van andere films zijn verwerkt. Om te beginnen die van Romero, maar voorts ook bijvoorbeeld The revenge of the dead (1960), The bride of the monster (1955) of The attack of the killer-tomatoes (1980). Om een idee te geven. En er wordt ook nog een lijst met cliché-monsters bij geleverd, van mutant tot flesh-eating aan toe.

Als uitgangspunt voor hun selectie beperkten de vakkringen zich tot speelfilms – dus geen documentair of educatief werk – van Engelstalige – lees: Amerikaanse – makelij. Niet dat in het Frans – Chacun son cinéma ou Ce petit coup au coeur quand la lumière s’éteint et que le film commence (2007, 18 woorden) -, Duits – Die Antigone des Sophokles nach der Hölderlinschen Übertragung für die Bühne bearbeitet von Brecht 1948 (Suhrkamp Verlag) (1992, 17 woorden) -, Spaans – Mil nubes de paz cercan el cielo, amor, jamás acabarás de ser amor (2003, 13 wooorden) – of Italiaans – Film d’amore e d’anarchia, ovvero ‘stamattina alle 10 in via dei Fiori nella nota casa di tolleranza… (1973, 17 woorden) – geen lange titels bestaan, maar Amerika ziet zichzelf graag als het centrum van de cinematografische industrie en dat is, eerlijk gezegd, niet eens helemaal ten onrechte.

Pseudo-humor

Mocht u niettemin de indruk hebben dat overdreven lange titels zich bij uitstek lenen voor slechte horror – Oh Snap! I’m trapped in the house with a crazy lunatic serial killer! (2008, 13 woorden) – of voor de pseudo-humor van films op het bedenkelijke niveau van I could never have sex with any man who has so little regard for my husband (1973, 16 woorden), dan wordt het tegendeel bewezen door de verfilming van The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum at Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (1967, 25 woorden). Die is gebaseerd op Marat/Sade, het van oorsprong Duitse toneelstuk van Peter Weiss, zoals gespeeld door de Royal Shakespeare Company. Het geheel draait om een toneelstuk – de moord op de Franse filosoof Marat – in de versie van de bewoners van het krankzinnigeninstituut Asile de Charenton in Noord-Frankrijk onder de regie van Marquis de Sade, die daar zelf lang heeft verbleven en er ook zou sterven.

Kort

Kort

De vraag naar de langste titel brengt automatisch ook de zoektocht naar de kortste mee. Om die eer strijden drie films, een Amerikaanse en twee Europese. Q (1982) heette oorspronkelijk The winged serpent, De gevleugelde slang, en dat zou al genoeg moeten zeggen. Een prehistorisch Azteeks afgodsbeeld komt tot leven in zijn nest bovenop een New Yorkse wolkenkrabber en zaait dood en verderf onder de betere kringen in Manhattan.

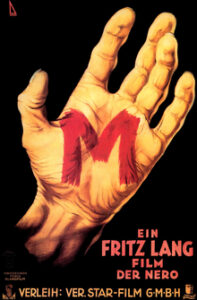

M (1931) van regisseur Fritz Lang is, in contrastrijk zwart-wit gefilmd, een klassiek voorbeeld van Duits expressionisme. Maar M (de afkorting voor Mörder) is vooral nog steeds de moeite waard om de angstaanjagende rol van Peter Lorre als kindermoordenaar.

Er werd in 1951 door Joseph Losey een remake van gemaakt, maar dat bleek een slap aftreksel. Het was ook de inspiratie voor Shadows and fog (1992), een van de betere Woody Allen films.

De tweede niet-Amerikaanse productie is Z (1969), het portret van Griekenland onder het kolonelsregime waarvoor regisseur Constantin Costa-Gavras de Oscar voor beste buitenlandse film werd toegekend. De film heette aanvankelijk The anatomy of a political murder, Z – Grieks voor “Hij leeft” – is het protestsymbool voor het slachtoffer van die moord.

Wim en Pim

Wim en Pim

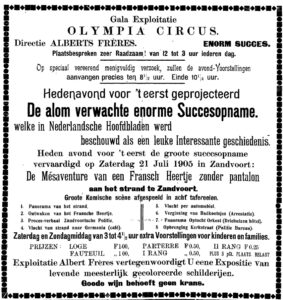

Wie onder Nederlandse films naar lange titels wil zoeken, heeft een indrukwekkende geschiedenis tot zijn beschikking. Opmerkelijke voorbeelden van ver vóór het digitale tijdperk zijn De mesaventure van een Fransch heertje zonder pantalon aan het strand te Zandvoort (1905, 13 woorden) en Het gestolen kind, door de trouwe Nero teruggevonden (1905, 8 woorden).

Maar echt op zoek naar lange Nederlandse filmtitels komt men al snel terecht bij het subsidieverslindende duo Wim Verstappen en Pim de la Parra, in de filmwereld bekend als “Wim en Pim”. Zij schonken ons films met namen als De minder gelukkige terugkeer van Joszef Katús naar het land van Rembrandt (1966, 12 woorden).

De intrigerendste is Mijn nachten met Susan, Olga, Julie, Piet en Sandra (1975, 9 woorden), die in de voorpubliciteit werd gepresenteerd als een “sex-psycho, suspense mystery thriller”, maar die in de praktijk, dat wil zeggen in de woorden van Ab van Ieperen in het NRC, werd getypeerd als “het werk van een niet onbegaafde filmamateur die op een landerige namiddag een ideetje heeft gekregen en dat onmiddellijk ten uitvoer heeft gebracht, zonder zich af te vragen of het eigenlijk wel zo’n goed idee was.”

Dat Pim de la Parra het ook alleen af kon, bewees hij met Paul Chevrolet en de Ultieme Hallucinatie (1985, 6 woorden). In Hollands Hollywood, dat een overzicht biedt van “Alle Nederlandse speelfilms van de afgelopen zestig jaar” (Amsterdam, 1995), doet Henk van Gelder een poging de chaos te schetsen te midden waarvan de film moest ontstaan.

Het is “het verhaaltje van een succesvolle, maar gescheiden thrillerschrijver, die doende is zijn relatie tot vrouwen te onderzoeken – of zoiets, want De la Parra was er de man niet naar om een strakke, glasheldere plot te ontwerpen.

Het is “het verhaaltje van een succesvolle, maar gescheiden thrillerschrijver, die doende is zijn relatie tot vrouwen te onderzoeken – of zoiets, want De la Parra was er de man niet naar om een strakke, glasheldere plot te ontwerpen.

Met de voornaamste acteurs werd een week gerepeteerd, waarbij iedereen naar hartenlust dialogen kon improviseren binnen de opzet. Karin Loomans noteerde die dialogen dan en stelde iets samen dat op een uitgewerkt draaiboek leek. Maar ook tijdens de opnamen was improvisatie nog mogelijk.”

Na de première is nooit meer iets van de film gehoord.

John O’Mill en de macaronische traditie

Er is een tijd geweest, lang vóór de Ryam- en de Beyoncé-agenda de klassen vrolijk kleurden, dat de agenda voor het nieuwe schooljaar door de school zelf werd verstrekt. Andere modellen waren uit den boze. Het waren dan ook saaie, grijzige notitieboekjes, zonder opsmuk.

Er is een tijd geweest, lang vóór de Ryam- en de Beyoncé-agenda de klassen vrolijk kleurden, dat de agenda voor het nieuwe schooljaar door de school zelf werd verstrekt. Andere modellen waren uit den boze. Het waren dan ook saaie, grijzige notitieboekjes, zonder opsmuk.

De enige frivoliteit die de ontwerpers zich veroorloofden, waren korte, lichtvoetige versjes, gewoonlijk rechtsonder op de zaterdag. Populair waren bijvoorbeeld C. Buddingh’, Daan Zonderland en Kees Stip; volwassenen kunnen dankzij die saaie agenda’s vaak nog klassieke regels uit het hoofd reciteren als

Ik ben de blauwbilgorgel,

Mijn vader was een porgel,

Mijn moeder was een porulan

van Buddingh’, of

Er zijn hier heel wat maden bij

die made zijn in Germanij

van Kees Stip, in de gedaante van Trijntje Fop.

Favoriet waren de rijmpjes van John O’Mill, het pseudoniem van de Brabantse docent Engels Jan van der Meulen (1915-2005). Ze waren grappig, eenvoudig te onthouden en dus altijd makkelijk te citeren. Een voorbeeld:

Rot young

A terrible infant, called Peter

sprinkled his bed with a gheter.

His father got woost,

took hold of a cnoost

and gave him a pack on his meter.

Of

Drents adrift

A hot headed Drent in Ter Apel

who always ran too hard from staple

forsplintered his plate

when the waitress was late

and gave her a lell with the laple.

Ze verschenen, behalve in die sombere agenda’s, in kleine boekjes met olijke titels als Lyrical Laria of Rollicky Rhymes, Bonny Ballads, an O’Mill medley of Verse & Worse, Curious Couplets, in Waals en Koeterwaals of – de mooiste – Popsy Poems. Pre-Popsylated Poetry. Rispe Rijmen in Dutch and double Dutch.

Ze verschenen, behalve in die sombere agenda’s, in kleine boekjes met olijke titels als Lyrical Laria of Rollicky Rhymes, Bonny Ballads, an O’Mill medley of Verse & Worse, Curious Couplets, in Waals en Koeterwaals of – de mooiste – Popsy Poems. Pre-Popsylated Poetry. Rispe Rijmen in Dutch and double Dutch.

(Korte taalles: double Dutch is Engels voor “onzin uitkramen”. Risp komt niet voor in het Nederlands en lijkt vooral door de dichter gekozen vanwege de mooie alliteratie met “rijmen”.

Pre-Popsylated wordt in een inleiding door de dichter zelf als volgt toegelicht: “All the verse in this bundle has been carefully and critically pre-popsylated by the author himself, so that any resemblance to art or poetry is purely accidental”. Het zal geen verbazing wekken, dat popsylated niet in de Engelse woordenschat voorkomt. Met wat goede wil kan nog gedacht worden aan een woordspeling met preposterous, volgens het woordenboek te vertalen met “ongerijmd”.)