Health communication in southern Africa: The Portrayal of HIV/AIDS in Lesotho Print Media: Fragmented Narratives and Untold Stories

No Comments yet Part II: Social Representations and Entertainment Education

Part II: Social Representations and Entertainment Education

Abstract

In late 2005, the Government of Lesotho launched the world’s first comprehensive plan to offer its entire adult population voluntary HIV testing and counselling. Using manifest and latent content analysis this study explores how articles in the two largest weekly newspapers in Lesotho portrayed HIV/AIDS and the campaign during seven month. While HIV/AIDS is frequently covered and recognised as a public health threat, the 227 articles rarely discuss the underlying causes, and do thereby not offer the reader information on the key driving forces behind collective and individual vulnerability to the virus. Moreover, the portrayal of HIV/AIDS as an insurmountable and overwhelming phenomenon could be counterproductive to efforts to get an entire population to test for HIV.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Lesotho

Lesotho is a small least-developed country completely encircled by South Africa with a population of 1.8 million. Among the adult population one in four is infected with HIV, making Lesotho one of the hardest hit nations in the world (Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, MoHSW, 2004; United Nations joint programme on HIV/AIDS, UNAIDS, 2006a; Word Health Organisation, WHO, 2005).

Immediate causes contributing to the dramatic increase in infection rates over the past two decades include unsafe heterosexual intercourse and mother to child transmission (World Bank, 2000). Underlying structural causes include widespread poverty and social dislocation because of migratory labor practices and gender inequality (World Bank, 2000; WHO, 2005) A recent positive result is that almost 94 percent of the population is reported to have ‘correct’ knowledge of HIV/AIDS. However, parts of the population still harbor a number of misconceptions about the HIV virus and only 24 percent of the women and 19 percent of the men are said to have comprehensive knowledge of both HIV transmission and prevention methods. Moreover, only 12 percent of men and 9 percent of women have gone for voluntary counselling and testing and know their HIV status (MoHSW, 2004). Today the epidemic in Lesotho has a mature pattern, similar to many countries in southern Africa, where the apparent stability in prevalence masks high rates of new HIV infections and even higher rates of AIDS-related deaths. In Lesotho, life expectancy has plummeted from 60 years in 1990-1995 to the most recent estimate of 42,6 years (United Nations Development Programme, UNDP, 2007) and 97,000 children are living as orphans due to parents dying of AIDS (United Nations Childrens Fund, UNICEF, 2006). High levels of morbidity and mortality increase demands on an already overstretched healthcare system and tend to impose a ‘shock’ to the household economy as it is often the economically active individual that falls ill and dies (World Bank, 2000a).

In 2003 the Government of Lesotho openly acknowledged the dire situation when the Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili warned: “we have to act NOW if we are to avert the potential annihilation of our nation” (emphasis in original document, Government of Lesotho/United Nations, 2003, p. xxiv) and in December 2005 the Know Your Status (KYS) Campaign was launched. The Know Your Status Campaign is the first attempt by any country in the world to provide universal HIV testing. The rationale behind the campaign is that voluntary counselling and testing is considered a key entry point into the components and activities of a comprehensive societal response. A comprehensive approach is generally expected to cover: prevention, treatment, care and support for those infected and affected by the virus, and impact mitigation (Barnett & Whiteside, 2006; Hewer, Motaung, Mathope & Meyer, 2005; McKee, Becker- Benton & Bertrand, 2004; UNAIDS, 2000, 2006a, 2006b; Weiser et al., 2006). The objectives of voluntary counselling and testing are to:

(i) detect infection early,

(ii) assist infected individuals to remain as healthy as possible,for as long as possible, by having access to available care and treatment services,

(iii) educate infected individuals to avoid infecting others

(iv) help individuals not infected to remain so through the maintenance of safe behaviour,

(v) assist individuals in life planning issues, and

(vi) assist individuals and couples in decisions about having more children, decreasing the chances of infecting infants (McKee et al., 2004:194).

A comprehensive response dominated by health interventions alone is insufficient to address the epidemic. Instead, a multi-sectoral approach that involves a broader range of stakeholders has since the mid 1990s gained ground as well as international recognition (Gavian, Galaty, & Kombe, 2006; United Nations, 2001, World Bank 1999b, 2003). Political leadership at the highest level is an absolute prerequisite for mobilizing a society’s response (Piot, 2000). Moreover, without actively addressing stigma and discrimination, many HIV/AIDS-related health services could remain unused. Hence, aside from the human rights aspect, fighting stigma and discrimination is pivotal in making the available services a real option for those who need them (UNAIDS, 2005). In the case of Lesotho, aiming for universal testing, as opposed to singling out population segments, could potentially have a destigmatizing effect as everyone is treated equally.

The official goal of the campaign is to have offered all those living in Lesotho who are over 12 years of age the opportunity to be HIV tested by end of 2007. The ambitious plan is to offer 1.3 million individuals the opportunity to learn their status. Post-test services will be offered according to HIV status (MoHSW, 2005). A key element of post-test services is the provision of anti-retroviral therapy for those who test positive for HIV and who are in need of medical treatment. The plan to provide anti-retroviral therapy to all who need it is particularly bold when taking into account the scale of the epidemic and the fact that, as of December 2005, only 8,400 individuals out of an estimated 58,000 in need of treatment actually received antiretroviral therapy (WHO, 2005). The strategy also regards the availability of treatment as a key-motivating factor for individuals accepting the offer of an HIV test. Thus, an initial and central objective of the communication component of the campaign will be to raise awareness around anti-retroviral treatment and its availability through messages via electronic and print media, as well as other advocacy material (MoHSW, 2006).

The Know Your Status Campaign communication strategy identifies national mass media as a crucial partner and as a way of building national and local

ownership of the campaign (MoHSW, 2006). Despite the radio’s overwhelming reach in Lesotho, television and newspapers are part of the Know Your Status Campaign communication channels as they are believed to be particularly effective in reaching opinion leaders such as cultural leaders, community elders and heads of official and traditional institutions at various levels. “Opinion leaders are important for ‘selling’ the programme to community members” (MoHSW, 2006, p.8). Without being mentioned a diffusion of innovation model is implied in the communication strategy.

Mass media are to be persuaded to participate and report on key events through consultative meetings and through capacity building workshops for interested journalists (MoHSW, 2006). In terms of readiness and perhaps even willingness to take part in a national effort, the Lesotho mass media already have shown its relative readiness to take on the issue. According to a recent study from Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA, 2006), Lesotho has the highest overall proportion of HIV/ AIDS coverage in Southern Africa. Lesotho print and electronic mass media mentioned HIV in 19 percent of the all the surveyed stories, compared to a regional average of just 3 percent. HIV/AIDS is also better mainstreamed into the general news coverage. In addition, 37 percent of the stories on the epidemic have HIV and AIDS as the focus, while it was a sub-theme in the rest. Lesotho mass media also carried a significantly higher proportion of locally originated stories than the rest of the region, which can have an impact on the readers’ perception of the issues relative relevance (MISA, 2006).

Not your typical communication challenge

More than 20 years into the HIV pandemic and despite countless information campaigns on prevention, anti-discrimination, treatment and care, a continuous rise in HIV prevalence, especially in southern Africa, has produced a number of studies questioning the straight forward relationship between information and changes in primarily long term sexual behaviour (James et al., 2005; Panos, 2003; Rogers & Singhal, 2003; UNAIDS, 1999a, b). One general conclusion from this work is that: Communication is necessary, but alone not sufficient for preventing HIV/AIDS, or augmenting care and support programmes. It should be noted that early communication efforts were successful in raising awareness of the existence of HIV/AIDS as well as knowledge on transmission modes (Bertrand, O’Reilly, Denison, Anhang & Sweat, 2006). Today, there is a growing acknowledgement that, in addition to spreading basic information, campaigns need to address the barriers that prevent the adoption of safer sexual behaviour more directly (McKee et al.,2004; UNAIDS, 1999a; 1999b).

There are several reasons why HIV/AIDS should not be treated as a typical communication challenge. A major factor is that, as a sexually transmitted disease, it is surrounded by numerous societal restrictions, taboos and moral codes, and often HIV infection is associated with promiscuity or immoral sexual behaviour (Aggleton, 2000; Delius & Glaser, 2005; Kelly, 2004). In southern Africa there is also a dimension of traditional rules guiding ‘pure’ and correct sexual behaviour, which implies that the disease cannot be regarded simply as “as a result of sexual promiscuity. It is also understood to be the outcome of breaches of critical sexual taboos. The afflicted are therefore seen as partly responsible for their own predicament” (Delius & Glaser, 2005, p. 33). Moreover, HIV has linked death to sexuality: “the two most powerful sources of ritual impurity and contagion” in many traditional African belief systems (Delius & Glaser, 2005, p. 33). Accordingly, all the ingredients for fear of the infected and subsequent strong stigma are present, and offer an explanation of the depth of stigma in southern Africa. Stigma is a social process characterised by exclusion, blame, or devaluation of a despised and/or minority group, and/or a blemished character or faults of the moral statue of an individual (Goffman, 1963). The function of stigma is to identify individuals perceived as threat to the rest of the community and exclusion is a manifestation of that fear (Douglas, 1966; Goffman 1963).

“Stigma is one of the major barriers to effective communication about AIDS” (Rogers & Singhal, 2003, p. 285). Others argue that it is the greatest challenge (Aggleton & Parker, 2002). HIV-related stigma and subsequent denial is a major barrier for recognizing HIV as a personal risk, and seeking voluntary counselling and testing (Countinho, 2004; Kalichman & Simbayi, 2003; Maclean, 2004; UNAIDS 2005). A study from South Africa showed that individuals who did not seek voluntary counselling and testing demonstrated greater AIDS-related stigmas and ascribed greater levels of shame and guilt, as well as social disapproval of people living with HIV (Kalichman & Simbayi, 2003). In Botswana, stigma was identified as a major factor in delaying testing (Wolfe et al., 2006). Even after the introduction of free anti-retroviral therapy in 2002 through the Masa project, HIVrelated stigma is a factor influencing the decision of accepting the offer of a routine HIV test, as well as planning to test among people not previously tested (Weiser et al., 2006). Findings from Botswana suggest that “success of large-scale national anti-retroviral therapy programmes will require initiatives targeting stigma” (Wolfe et al., 2006, p. 931), if they are to be successful. In this context it is important to note that there is nothing ontological about stigma. Social attitudes and fears connected with certain behaviours, groups, diseases, and so forth have always been under contestation, and can and do change.

Another factor making HIV/AIDS communication particularly challenging is its interconnectedness with embedded power structures. Three aspects influence sexual practices on both the individual and societal level: knowledge, rationality, and power relations (Ek, 1996). Accordingly, power relations determine what knowledge is to be socially sanctioned and acted upon, sometimes making it impossible for prevention messages to be realised into safer sexual practices. In terms of sexuality, “power determines whose pleasure is given priority as well as when, how, and with whom sex takes place” (Gupta, 2000, p. 2) Gender inequality is a key driving factor in the epidemic (Baylies & Bujra, 2000; Gupta, 2000). As such, “AIDS is not only an information problem, but a manifestation of an unequal power distribution between the sexes” (Ek, 1996, p. 146).

Poverty exacerbates the already unequal power distribution and skews the rationality concept. “Extreme poverty deprives people of almost all means of managing risk themselves” (World Bank, 2000b p. 1). Poverty forces individuals to make long term ‘irrational’ choices, as it makes them less likely to adopt safer behaviours if long term rewards collide with short-term access to immediate resources (Barnett & Whiteside, 2006; Kalipeni, Craddock & Gosh, 2003; Rogers & Singhal, 2003).

An epidemic is par excellence a collective event. While individuals do have responsibility for their actions, that responsibility has always to be considered in a context of what individuals can do given the structures of inequality and the histories within which they live their lives (Barnett & Whiteside, 2006, p. 79).

Thus, interventions need to broaden their focus from merely targeting the individual to persuading him/her to adopt new safer behaviours, to include addressing relevant structural constraints or altering those in conflict with the safer new behaviour (Barnett & Whiteside, 2006). In short, a “fundamental step is to realise that the HIV/AIDS epidemic is not just a biomedical and health problem. It represents a political problem, a cultural problem, and a socio- economic problem” (Rogers & Singhal, 2003, p. 389), and, as such, it can never be successfully addressed by public health campaigns alone.

Having acknowledged the barriers for effective communication in terms of soliciting behavioural change does not imply that public health campaigns cannot promote health messages. A recent 10-year research review of health mass media campaigns concludes

… that targeted, well-executed health mass media campaigns can have small to moderate effects not only on health knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes, but on behaviours as well, which can translate into major public health impact given the wide reach of mass media (Noar, 2006, p. 21).

Mass media in western countries are a major source for both correct and distorted information on HIV/AIDS (Lupton, 1994; Rogers & Singhal, 2003). A recent review of mass communication programmes to change HIV/AIDS related behaviours in developing countries, showed a small to moderate effect on knowledge levels and a range of behaviours (Bertrand et al., 2006). The study concludes that mass media did have a positive impact when it came to increasing knowledge of HIV transmission and reduction of high-risk sexual behaviour (Bertrand et al., 2006). Mass media campaigns in the developing world have also proven to be able to both promote favourable attitudes on voluntary counselling and testing and provide information on where to access the services (McKee et al., 2004). Research from Zimbabwean HIV testing centers showed that 64 percent of the clients learned about the voluntary counselling and testing services through mass media (McKee et al., 2004). In Botswana, 69 percent of voluntary counselling and testing attendants reported that a television or radio message had facilitated their decision to accept the offer of a routine HIV test (Weiser et al., 2006). In addition, it has been argued that mass media can offer space for and be a part of creating an enabling and supportive societal climate for discussing HIV, stigma and discrimination, as well as, encouraging leaders to take action and keep policymakers and service providers accountable (UNAIDS, 2004). A study of 15 African countries identifies the higher a person’s level of formal education and the more often he/she read newspapers, the more likely they are to cite HIV/AIDS as an important public problem (Afrobarometer, 2004). Subsequently, it could be argued that newspapers potentially could facilitate an educated elite readers’ understanding of HIV/AIDS as a public priority.

Mass media can, through its portrayal and selective use of language, “trivialise an event or render it important; marginalise some groups, empower others; define an issue as an urgent problem or reduce it to a routine” (Nelkin, 1991 cited in Lupton, 1994 p. 22). This study examines print media content, by using a method that combines elements of systematic content analysis and more interpretive examinations of the properties of the portrayal of HIV/AIDS in general and the Know Your Status Campaign in particular in two weekly newspapers in Lesotho.

Method

The method is ‘quasi quantative’ as it relies on a number of quantifications and statements of frequency of the manifest features of the texts (Berleson, 1952). Still, the study relies more on a qualitative ethnographic approach to capture the more complex discursive formations in the texts.

Print media were selected as the Know Your Status Campaign communication strategy identifies this channel as a key channel to reaching key opinion leaders who are thought to be crucial for campaign success. While Lesotho has an adult literacy of 81.8 percent (Government of Lesotho/DLSSD, 2002), newspapers are primarily available in the urban areas and are regarded as a vehicle to reach elite audiences. Unfortunately, there are no reliable circulation data. Moreover, we anticipated a difference in coverage of the government initiated Know Your Status Campaign within a government channel as opposed to a privately owned and run channel. The radio scene is dominated by Radio Lesotho, and lacks a privately owned equivalence in terms of content to the state channel. Using print media had the additional advantage that, unlike the electronic media, there are comprehensive archives.

Sampling procedure

There are no daily newspapers in Lesotho, but a number of weeklies. The government-owned and operated newspaper, Lesotho Today, which has the widest geographical distribution, and the largest overall circulating paper, the privately owned, Public Eye were selected. Both papers devote half of their space to articles in English and the other half carries the same articles in the indigenous language, Sesotho. Both languages are official languages in Lesotho. The period under study runs from the Know Your Status Campaign launch date on December 1st 2005 and for 7 months until the end of June 2006. This time frame was selected to include the reporting of the campaign launch on World AIDS Day, but extended to provide a large enough sample with ‘regular’ HIV/AIDS coverage during the first year of the campaign. Only the month of December could be said to be an a-typical month as the events around the Know Your Status Campaign launch and world AIDS Day both occurred during that month. During the sample period, only April featured any significant Know Your Status Campaign outreach event as the campaign secretariat spent most of the early months of 2006 by conducting baseline studies, formulating a communication strategy, preparing information materials.

The content analysis was carried out only on the English section. All articles in the English sections including the words ‘HIV’ or ‘AIDS’ were included in the sample and the total number of articles included in the analysis amounted to 227 of various lengths. Paid space, such as public service announcements, HIV/AIDS banners from local or international NGOs or government was not included.

Manifest and latent content analysis

By analyzing press representations of HIV/AIDS insights into a society’s broader socio- cultural constructions around, not only HIV/AIDS, but disease, illness and health can be gained (Lupton, 1994). The content analysis and subsequent coding aimed at identifying reoccurring public discourses on HIV and AIDS. A discourse was identified as ways of organizing meaning, that are often, though not exclusively, realised through language.

The study looks at both manifest (obvious and explicit content and characteristics of the text) and latent (unintended or sub-textual content). A coding scheme was developed inductively after numerous readings and re-readings. The scheme included a part that registered the frequencies of manifest elements of the articles, and a second part that initially focused on latent features of the texts, such as the dominant and obvious narratives interwoven into the manifests elements of the text. This section was expanded to also include the absent discourse – causes of the epidemic. The method for the more interpretive and in-depth examination of the texts was inspired by an ethnographic content analysis (Altheide, 1996). The manifest analysis focused on registering:

a) if HIV/AIDS was the primary or secondary focus on the article,

b) if the content was local or international in its focus,

c) in what thematic surface context HIV/AIDS was dealt with (see Table 2 for surface themes and distribution), and

d) what kind of article HIV/AIDS appeared in, that is: news article/feature story/opinion piece/column, reader’s letter, review and whether the article made it to the front page.

An article was coded as a feature story if the content had one or more of the following characteristics: a human interest story, well researched investigative exposé, conversation piece, personal experiences, personality profile, or a piece of timeless nature. All articles with a clear viewpoint or with a clear intention to persuade the reader were coded into one of the following categories: opinion piece/column, editorial, reader’s letter or review.

In addition, all articles were checked for e) statistics describing facts about the epidemic, for example prevalence rate, death rates, number of orphans and so forth. Quantification in health news stories is of particular importance. By providing statistics, the statements made in the article are substantiated, as well as give the reader with an impression of objectivity. Statistics showing to what scale something has happened also enhance the value of the news story and add drama. (Lupton, 1994). However, no attempt was made to evaluate the accuracy of the factual information in the articles. Finally all articles were scanned for f) if the article carried information on the Know Your Status Campaign, and, if so, whether the information was comprehensive.

The latent content analysis scanned for reoccurring narratives around the epidemic, and features of those very same narratives. The focus on narratives led to the inclusion of an examination of absence of certain features in those very same narratives.

Results

Content analysis

The manifest and latent text analysis provided two complementary sets of results. Through the manifest content analysis it could be concluded that HIV/AIDS is well featured both as a stand-alone topic and as a mainstreamed secondary focus throughout the material. HIV/AIDS is, however, rarely front-page material. Only 6 out of the 227 articles made it to the front page. For the privately owned Public Eye, HIV/AIDS was well integrated into the entire newspaper: news articles, feature articles, opinion pieces /columns, editorials, reader’s letters, and reviews (Table 1). Lesotho Today covered HIV/AIDS only in news, feature articles and editorials.

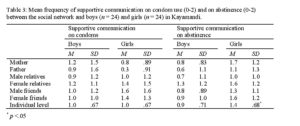

Table 1. Number and percentage of article types by primary versus secondary focus on HIV/AIDS in two newspapers.

News articles appear to be the main type of article to carry HIV/AIDS content for both papers. Feature articles did not carry more comprehensive narratives on HIV/AIDS, that is, descriptions of the epidemic’s immediate and root causes or inclusion of people living with HIV/AIDS, than did news articles. As for the government newspaper, Lesotho Today, feature articles were less frequent in general and HIV/AIDS content never appeared in readers’ letters, opinion and columns. Lesotho Today did not carry reviews. In almost half (45 percent for Public Eye and 42 percent for Lesotho Today) of all the articles, HIV/AIDS was featured as the main theme, which is consistent with the findings of the aforementioned 2006 Media Institute of Southern Africa’s study. Of the total 227 articles, 79 percent had a local Lesotho focus, that is, the focus of the article was featuring local conditions or interviewees was either Mosotho or both. Another interesting feature is the frequency of editorials, 11 in total. The high percentage of articles featuring local conditions instead of bought regional or international material in combination with the frequency of almost an editorial a month could indicate that newspapers do perceive HIV/AIDS as an important issue to cover.

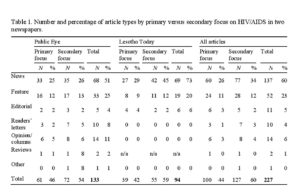

In terms of the context in which HIV/AIDS is covered either as main focus or as a complimentary focus, all articles were sorted into exclusive categories of surface themes. Table 2 presents the ten most frequent surface themes in which HIV/AIDS occur in the sample. The ten categories include 86 percent of the sample. The remaining articles were distributed over a number of smaller categories. In terms of what contexts HIV/AIDS occur, International Development Cooperation, that is, technical and financial assistance provided by external donors to development programmes in Lesotho, is the most frequent context for HIV/AIDS.

This category is closely followed by Government and Governance that includes coverage of the Lesotho government, ministers and government officials’ communication and initiatives. There is however a clear difference between the two papers and their coverage of the Government of Lesotho. The state run and owned newspaper Lesotho Today covers HIV/AIDS in this context far more often (27 percent of the 94 articles) than Public Eye (eight percent). The third most frequent surface theme in which HIV/AIDS appear is Lesotho Health Care System. The potential implications of placing and constructing narratives around HIV/AIDS in these contexts are elaborated upon in the discussion. Another interesting feature of the surface themes is the similarities in the respective papers’ topical prioritisation. The use of quantification and provision of statistics as a journalistic tool to add weight to a news piece is used eight percent in the government paper Lesotho Today. In the Public Eye sixteen percent of the articles contained a quantification of the epidemic. In terms of the frequency of the Know Your Status Campaign, fourteen percent of the articles included coverage of the Campaign. However, only six articles provided comprehensive information on what the campaign actually entails. There was no discernable difference between the two papers in terms of covering the national Know Your Status Campaign.

Dominant narratives on HIV/AIDS

While HIV/AIDS is found to be frequently featured in both papers, an equally important question relates to how the epidemic is covered. That is, how the print media construct the epidemic in a recognizable universe for its Basotho readers. The quantitative analysis gave a basic structure, but provides little insight into the ‘maps of meaning’ that are provided by the media texts (Hall, Critcher, Jefferson, Clarke & Roberts, 1978). The following section presents only the dominant narratives that emerged through the more interpretative qualitative analysis. The reader should therefore bear in mind that the material also contains other narratives. Somewhat simplified it could be argued that there is only one dominant narrative, that of the devastating consequences of the epidemic that runs through the articles. This meta narrative is ever present and serve as a backdrop for coverage of international cooperation, crime, children and youth, the Lesotho Health Care System’s struggle to deliver services to an ailing population, Government response and so forth. This dominant narrative in turn carries a number of sub-themes, where the epidemic’s consequences on children, individuals, communities, and the Basotho society are elaborated on. Of equal importance is often what is not covered in the articles and the latent text analysis came to focus especially on uncovering the untold narratives on HIV/AIDS.

Consequences of HIV/AIDS

The consequences of the HIV epidemic on individual lives, community and society at large were a dominant narrative through the entire period. Three themes are particularly well covered:

a) the impact on children and the growing numbers of orphans and vulnerable children,

b) HIV and AIDS as a cause of death and disintegration of communities, and finally,

c) the negative impact on the country’s overall socio-economic development. These narratives are intertwined with news articles whose main focus is to cover for example a new international cooperation programme or local, regional activism and voluntary work.

The impact on children and the growing number of orphans and vulnerable

children (OVC in the news articles below) is one of the most dominant themes. The plight of children in the midst of the epidemic is both a surface theme in its own right, but also a narrative that is closely connected to other coverage. HIV/AIDS is not only identified as the underlying factor for the increase of orphans in Lesotho, but the articles also elaborate on the consequences for affected children. The real impact of the disease on Lesotho’s children is recognised and form a central part of the print media’s discourse:

Humanity is grappling with the invisible killer on the rampage, devouring millions and leaving stranded orphans behind (Public Eye 17-22 /3 2006). The HIV/AIDS pandemic continues to cripple economies and to rob children of their childhood (Lesotho Today 8-14/12 2005).

Our government’s endeavours to fight the spread of this scourge that continues to kill young men and women at their prime age, whom in most instances are breadwinners leaving thousands of children as orphans (Lesotho Today 1-7/12 2005).

The consequence of HIV/AIDS is the increasing number of OVCs and that OVCs live in a viscous cycle of food insecurity, disease and lack of care and education resulting in malnutrition and high mortality (Lesotho Today 26/1-1/2 2006). HIV/AIDS has redefined childhood. Children are left to grow alone without their primary line of protection- parents and they are left vulnerable to abuse, exploitation and violence (Public Eye 2-8/12 2005).

Another sub-narrative is HIV/AIDS as a cause of death and disintegration of communities, along with the devastating effects on macro-demographics:

People are buried every weekend due to deaths caused by HIV/AIDS or other related illnesses (Lesotho Today 13-26/4 2006).

At this rate of dying this village will soon be wiped out … we are burying a child or adult victim of AIDS almost every day” (Public Eye 3-8/2 2006).

In Lesotho, many families have been devastated by the deadly disease of HIV, and the situation seems to be worsening from day to day (Lesotho Today 25-31/5 2006).

HIV/AIDS has affected not only the size of population but also the age and sex composition and structure of the population (Lesotho Today 2-8/3 2006).

Between 2003 and 2005, HIV/AIDS and its associated disease conditions continued to make an unprecedented impact on Lesotho’s population structure (Public Eye 21-27/4 2006).

The material also includes a number of accounts of the epidemic’s negative impact on the overall development of the country as the productive segments of the population fall sick and die. The texts also highlight the fact that the epidemic is an added burden on the government’s budget. This theme was primarily covered by the government owned newspaper:

HIV/AIDS pandemic is a barrier to development as people with skills often die of this disease (Lesotho Today 22/12- 4/1 2006).

The most productive people who can bring the difference or development in the country are the most affected by the pandemic (Lesotho Today 13-26/4 2006).

If HIV/AIDS is still cleaning up the nation, most of the development will come to halt (Lesotho Today 27/4-3/5).

The future looks bleak for Lesotho (Lesotho Today 27/4-3/5).

This year’s budget will see some of the governments projects being put aside more funds into fighting the disease (Lesotho Today 16-22/2 2006).

Know your status campaign, voluntary counselling and testing and treatment literacy The Know Your Status Campaign is awarded positive coverage. The initiative is often presented as the government’s greatest response to date. The articles often report of the praise given to the campaign by the international community. The fact that Lesotho is the first country in the world to attempt to offer all its citizens voluntary counselling and testing, seems to be highlighted with a sense of national pride.

Basotho know that they are fighting for survival. Words like extinction and annihilation are commonplace. The Know Your Status Campaign is meant unflinchingly to confront the unthinkable (Public Eye 17-22 /3 2006). In a ground breaking move, the government has planned to introduce door-to-door HIV/AIDS testing and counselling as a measure (Public Eye 23-29 /12 2005). The first time in history for a door to door … campaign (Lesotho Today 22/12 2005). In a landmark move, Lesotho would become the first country in the world to offer door-to-door HIV/AIDS voluntary counselling and testing (Public Eye 30/12 2005 – 5/1 2006). Lesotho’s Know Your Status campaign, the first of its kind worldwide (Public Eye 5-11/5 2006).

The positive effects of anti-retroviral therapy are described, but the information is far from comprehensive in the sense that correct information on when treatment can be started, that treatment is a lifelong commitment and that full adherence is very important but seldom achieved. Potentially coverage of the positive effects of anti-retroviral therapy can be a motivating factor for accepting the offer of Voluntary Counselling and Testing:

Let’s all know our status because it is only then that those infected can receive appropriate treatment (Public Eye 6-12/1 2006).

Testing HIV positive was like a death sentence, and for many people this signaled the end of their lives. However, the situation has significantly changed thanks to life-prolonging anti-retroviral treatment. (Public Eye 3-9/3 2006).

I started treatment … I feel very healthy now and can easily go around my daily chores … working in the fields (Public Eye 30/12 2005 -5/1 2006).

He could now work the fields (Public Eye 3-9/3 2006).

The reference point of being able to continue farming thanks to anti-retroviral therapy is reoccurring in the material and, for a rural society, an easily recognised benchmark for being healthy. Despite the clear link between testing and access to anti-retroviral therapy, it cannot be said that the articles provide essential medical information on the complexities of treatment. It is, therefore, debatable whether or not it can be claimed that print media are raising the level of treatment literacy in any substantial way.

The absent discourses on causes

The elaborate descriptions of the devastating impact of the epidemic create an impression that the Lesotho print media are fulfilling one of the basic missions of journalism: cover events of relevance to the readers. However, the results of the latent text analysis show that both immediate causes, transmission through mother to child, and through unsafe blood, as well as root causes: poverty, gender inequality and social disruption due to labour migration, are more or less absent in the material. Transmission through sex is featured, but burdened by moral judgments. This fragmented narrative on HIV/AIDS and the exclusion of the epidemic’s immediate and root causes cannot be derived from the lack of country-specific data, as the facts on the causes are almost as conclusive as that of the consequences.

HIV/AIDS is predominantly a heterosexually transmitted disease in Lesotho and aside from a few exceptions, most notably some neutral statements done by the Prime Minister of Lesotho, sex and HIV infection are intimately linked to bad morals. The discourse on moral and blame ranges from open statements of condemnation, to being silently implied by the type of sexual behaviour described, such as sodomy, prostitution and rape, all of which are regarded as social ills in traditional Basotho society.

The illicit wanderings of men and women for heterosexual indulgence are disastrous … HIV/AIDS is predominantly spread through secretion of the sexual organs which normally occurs in cases of illicit sexual practices out of wedlock (Public Eye 16-22 /12 2005).

Introduction of the [teaching of] use of condoms in school, apart from being sinful, is indeed justification and opening the door for immoral lifestyles (Lesotho Today 19/1-25/1 2006).

They [Government of Lesotho] supply the community with condoms, and gloves, adding that in prisons they do not promote sodomy as it is a crime, but they supply them with prevention of HIV/AIDS (Lesotho Today 23-29/3).

Changes have been employed in prisons to fight HIV/AIDS which is reported to be rife due to sodomy and other factors that make prisoners prone to adulterous activities (Lesotho Today 13-26/4).

We are under the state of emergency and cannot afford to give priority to people rights to privacy over the need to stop the massacre of our people. Prostitution, as one of the sources of spreading the disease, must also be put under control (Public Eye 6-12/1 2006).

Be faithful to one partner. Which many of us interpret as ‘be as faithful as practicality, convenience, peer pressure and other factors permit. In Lesotho, the biggest problems are massive urbanisation and erosion of good cultural and religious values, the endemic alcoholism, the influence of media such as television, and the fact that most employed people do migrant work (Public Eye 9-15/12 2005).

Sexual intercourse as a mode of transmission and cause of HIV infection is not absent from the texts like transmission between mother and child, the other main mode of HIV infection in Lesotho, nor is it nearly absent as in the case of transmission through unscreened blood. The main structural causes of Lesotho’s HIV pandemic: widespread poverty, gender inequality and social dislocation due to a system of migrant workers are with a few exceptions all absent in the material. The potential implications of this fragmented portrayal disconnected from the realities of the epidemic in Lesotho, combined with the last discourse of hopelessness and defeat, will be discussed momentarily.

A sense of hopelessness and defeat

Instead of providing the reader with a whole narrative HIV/AIDS, some texts feature the HIV epidemic as a phenomenon threatening to destroy the nation. More worrisome, this discourse also portrays struggle against this unavoidable fate as being futile and hopeless.

HIV/AIDS pandemic continues to wreak havoc to our nation … We learn in some African countries like Uganda and Zimbabwe scourge of this disease is declining, but with us here the situation is gloomy” (Lesotho Today 16-22/2 2006).

The entire Basotho nation will be doomed if Basotho continue to ignore the disease in a manner that they are doing presently (Lesotho Today 8-12/12 2005).

Any discussion about the future must take full cognisance of the frightening scourge of HIV/AIDS pandemic which threatens to wipe off the entire African continent, including Lesotho, from the face of the earth (Lesotho Today 25-31/5 2006).

HIV/AIDS as a tragic event that the human mind cannot dissect. It shows how humanity is grappling with the invisible killer on the rampage, devouring millions and leaving stranded orphans behind (Public Eye 17-22 /3 2006).

Besides describing the worst possible scenario – the annihilation of the nation – the material presents a picture where past interventions aimed at escaping such a fate have rendered little result.

Despite massive HIV/AIDS campaigns very little behaviour change has been observed (Public Eye 5-11/ 5 2006).

The government, church organizations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), small groups and the business sector exerted conceited efforts to arrest the escalation of the scourge, but it seemed all these efforts were no avail. The scourge is increasingly annihilating the nation and has made it prone to extinction (Public Eye 13-18/1 2006).

HIV/AIDS remains a huge mountain for nations to climb as amidst programmes and policies that government have, the number of new infections keep on increasing daily and alarmingly (Lesotho Today 8-14/12 2005).

The pandemic which continues to deprive Basotho of their valuable lives as the numbers of those infected and affected are continuing to increase. This despite all efforts applied to contain the disease (Public Eye 6-12/1 2006).

The state of affairs is forcing the country’s social structure to gradually collapse, leaving little room for hope in people’s mind (Public Eye 16-22/12 2005).

The two words extinction and annihilation have become common place for Lesotho and Swaziland, Africa’s only functional kingdoms as far as the fight against HIV/AIDS is concerned (Public Eye 17-22 /3 2006).

Discussion

Mass media through its selections, omissions and interpretations visible through its contextual frames and narratives, provide its audiences with social constructions of numerous topics. An issue can be trivialised or awarded great importance and call for the audience attention. This paper set out to attempt to identify some of the components available to the Lesotho readers in a time when their country is making a bold move to address the HIV epidemic through increased voluntary counselling and testing. Naturally, mass media are one out of many channels to provide the Basotho people with information that contributes to their understanding of the HIV epidemic.

In a regional comparison, according to the Media Institute of Southern Africa (2006) the Lesotho mass media in general prioritise HIV/AIDS coverage both in terms of frequency and framing the epidemic in a local and culturally relevant context. In this study of two weekly Lesotho newspapers both the privately owned Public Eye and the government owned Lesotho Today provides space to cover the HIV/AIDS epidemic from a number of perspectives. On average these weekly newspapers each carry 16 articles that include HIV/AIDS every month. Moreover, both papers award editorial space to the issue and thereby signal that they regard HIV/AIDS as an important issue for commentary. The salience given the epidemic is positive, but hardly surprising. In a high prevalence country such as Lesotho, the impact of the epidemic is so tangible for all citizens that failure to acknowledge or consistently misrepresent the everyday realities would be incompatible with the print media’s most basic news delivery function. Without coverage of the epidemic, the newspapers would most likely appear more or less fictional even to the most uncritical reader.

Counterproductive social messages

In a time when the government of Lesotho is making an attempt to offer their entire adult population a voluntary counselling and testing, the inclusion of HIV/AIDS in the newspapers’ editorial and ordinary news agenda is positive. However, of perhaps even greater importance is how the epidemic is constructed and framed for the reader. From a Know Your Status Campaign perspective it could be of interest to try to understand various mass media constructions of how the epidemic is to be understood and acted upon, and if needs be fine-tune future Voluntary Counselling and Testing messages accordingly. Returning to this study, it could be interesting to further investigate what the implications are of placing HIV/AIDS to a large extent in the context of international development cooperation, government, and the Lesotho health care system. By framing HIV/AIDS discursively as an issue closely connected to national and international institutions far away from the individual there is a potential risk the epidemic is perceived as an issue which is the responsibility of these very same institutions.

Moreover, strong narratives on the devastating consequences of the epidemic, such as high death rates due to HIV/AIDS, disruption of communities, changing demographics, an escalating orphan crisis, adverse impact on the economy and the overall development of the country, might even further construct HIV/AIDS as an overwhelming force beyond the control of the individual. In addition, fragmented narratives on the epidemic’s causes that denies the reader any real understanding of why Lesotho is so severely affected, in combination with a defeatist discourse might fuel a reading of the articles that the HIV epidemic is too large and incomprehensible to act against. This interpretation of the epidemic is not conducive to create a momentum for mass HIV testing. In short, fragmented narratives on the causes of HIV/AIDS, combined with a defeatist portrayal of the epidemic, does not encourage social mobilisation or social action of key opinion leaders needed to make the campaign successful. If the struggle against HIV/AIDS individually and collectively is portrayed as futile, inaction is an unfortunate but rational behavioural response.

Despite that the two surveyed newspapers provide space and positive coverage for the national Know Your Status Campaign during the first seven months of the campaign period, a moralistic discourse on sex could also be counterproductive.

Framing HIV/AIDS and sexuality in a way that further deepens stigma and discrimination, could contribute to denial of personal risk and adversely affect the perceived need for an HIV test. The strong social stigma associated with HIV/AIDS and the human response of denial has proven to be a strong adversary when it comes to getting individuals to go for voluntary counselling and testing, even when it is the only way to access life-saving treatment.

HIV/AIDS as a facilitator of change Ek (1996) discusses how an epidemic is an extraordinary event and thereby often inconsistent with previous experiences. A situation where previous experiences and ways of organizing human relations no longer can guide future interaction, has a great potential to open up for social change. An epidemic can therefore create space for actors who wish to challenge existing beliefs, norms, attitudes and practices (Ek, 1996). A situation where a virus is spread slowly and by known channels, like the HIV virus, should provide excellent preconditions for deliberation and subsequent adjustment of the social practices making individuals and communities vulnerable.

In countries where putting an ever increasing number of people on expensive life prolonging anti-retroviral therapy is not an option, changed sexual practices is the only sustainable strategy for both the individual and the society at large to gain control over the epidemic. According to LaFont and Hubbard (2007), the HIV epidemic has assisted countries in Southern Africa to expose the social structures and open up space to discuss previous social taboos, such as patriarchal power structures, gender inequality, sex and sexuality and so forth. The sheer impact of the epidemic has forced these previously off-limit topics into the limelight, and enabled social actors to openly challenge them.

In the case of the Public Eye and Lesotho Today, the discourse on sex and sexuality, as well as the absent coverage of power relations that guide sexual

relations and practices, are conspicuous, even if not surprising. Sexuality and entrenched gender inequality are socially sensitive and highly provocative topics, and here the two media outlets choose to play it safe, and omit them from their narratives around the epidemic. By merely reproducing the status quo in terms of gender inequality, sexual practices, and so forth, the articles fail to draw much needed attention to the complexity of the disease as well as the need for changing individual behaviours. Through omission of gender inequality and sexual practices, the opportunity to provide the reader with a more comprehensive understanding of both the epidemic and their own vulnerability is lost. A clear and neutral acknowledgment of current sexual behaviour and practices as the main cause for the epidemic would highlight each individual’s responsibility to take action.

HIV/AIDS has been part of the public agenda for some 20 years and will in the absence of a vaccine continue to have a significant impact on life in Lesotho.

Awarding this ever-present epidemic with timely, accurate, non-discriminatory, and informative coverage is no doubt going to be a challenge. More comprehensive narratives that do not shy away from the socially controversial aspects of the epidemic could solve this problem for some to come.

While the Know Your Status Campaign ended in December 2007, efforts to decentralise voluntary counselling and testing is planned to continue even after 2007. According to a World Health Organization press release in April 2008, 240 000 people in Lesotho knew their status at the end of 2007, and that 30 of the tests had been conducted in community-based settings. The author has been unable to find reliable statistics on how many individuals were tested as a result of the campaign.

References

Afrobarometer. (2004). Public opinion and hiv/aids: Facing up to the future? (Afrobarometer Briefing paper No 14). Retrieved February 1, 2008 from www.afrobarometer.org/papers/AfrobriefNo14.pdf.

Aggleton, P. (2000). HIV and AIDS-related stigmatization, discrimination and denial: Forms, context and determinants. Geneva: UNAIDS.

Aggleton, P., & Parker, R. (2002). World AIDS campaign 2002-2003. A conceptual framework and basis for action: HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination. Geneva: UNAIDS.

Altheide, D.L. (1996). Qualitative media analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Barnett, T., & Whiteside, A. (2006). AIDS in the twenty-first century: Disease and globalization. Second Edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Baylies, C., & Bujra, J.M. (2000). AIDS, sexuality and gender in Africa: Collective strategies and struggles in Tanzania and Zambia. London: Routledge.

Bertrand, J., O’Reilly, K., Denison, J., Anhang, R., & Sweat, M. (2006). Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass communication programmes to change hiv/aids-related behaviours in developing countries. Health Education Research, Theory and Practice, 21(4), 567-597.

Countinho, A. (2004). Challenging links involved in research policy-implementations – moving from national policy to free provision of ARVs in Uganda. In Sida (ed.) Forging the links against AIDS (pp. 49-56). Stockholm: Sida.

Delius, P., & Glaser, C. (2005). Sex, disease and stigma in south africa: Historical perspectives. African Journal of AIDS Research, 4, 29-36.

Douglas, M. (1966). Purity and danger: An analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo, London and New York: Routledge.

Edgar, T., Fitzpatrick, M.A., & Freimuth, V.S. (1992). AIDS: A communication perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

EK, A-C. (1996). Kenyanska AIDSdiskurser: En studie av AIDSinformation i Kenya och dess betydelse för kvinnors och mäns sexuella relationer i Luosamhället. Umeå: UmU Tryckeri.

Gavian, S., Galaty, D., & Kombe, G. (2006). Multisectoral HIV/AIDS approaches in Africa: How are they evolving. In S. Gillespie (ed.), AIDS, poverty, and hunger. Challenges and responses. Washington: IFPR Publications Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma, notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York.

Simon and Schuster Government of Lesotho & United Nations/UN (2003). Turning crises into an opportunity strategies for scaling up the national response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic in Lesotho. New York: Third Press Publishers.

Government of Lesotho/DLSSD (2002). Lesotho Core Welfare Indicators Questionnaire, CWIQ Survey. Unpublished report.

Gupta, G.R. (2000). Gender, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS: The what, the why, and the how. Paper presented at XIIIth International AIDS Conference. Durban, South Africa 2002.

Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J., & Roberts, B. (1978). Policing the crises: Mugging, the state, and law and order. London: MacMillan Press.

Hewer, R., Motaung, E., Mathope, A. & Meyer, D. (2005). Social marketing as a means of raising community awareness of HIV voluntary counselling and testing site in Soweto, South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research, 4, 51-56.

James, S., Reddy, P., Ruiter, R.A.C., Taylor, M., Jinabhai, C.C., Van Empelen, P., & Van Den Borne, B. (2005). The effects of a systematically developed photo-novella on knowledge, attitudes, communication and behavioural intentions with respect to sexually transmitted infections among secondary school learners in South Africa. Health Promotion International, 20, 157-165.

Kalichman, S., & Simbayi, L. (2003). HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 79, 442–447.

Kalipeni, E., Craddock, S., & Gosh, J. (2003). HIV and AIDS in Africa: Beyond epidemiology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Kelly, M. (2004). Ethical considerations of HIV/AIDS research in Africa. In Sida (Ed.), Forging the links against AIDS (pp.9-18). Stockholm: Sida.

LaFont, S., & Hubbard, D. (2007). Unraveling taboos – gender and sexuality in Namibia. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

Lupton, D. (1994). Moral Threats and Dangerous Desires. AIDS in the News Media. London: Taylor& Francis.

Maclean, R. (2004). Stigma Against People Infected With HIV Poses a Major Barrier to Testing. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30, 103.

McKee, N., Becker- Benton, A. & Bertrand, J. (2004). Strategic Communication in HIV/AIDS Epidemic. New Delhi: Sage.

Meyer-Weitz, A. (2005). Understanding fatalism in HIV/AIDS protection: The individual in dialogue with contextual factors. African Journal of AIDS Research, 4, 75-82.

Media Institute of Southern Africa [MISA]. (2006). HIV and AIDS and gender baseline study. Media Institute of Southern Africa. Retrieved August 2007 from www.misa.org.

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare [MoHSW] (2004). Lesotho demographic and health survey 2004. Maseru: Government of Lesotho.

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. (2005). Know Your Status Campaign operational plan 2006-7- gateway to comprehensive HIV prevention, treatment, care and support. Universal access to HIV testing and counselling. Government of Lesotho. Unpublished document.

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. (2006). ‘KYS communication strategy’, Government of Lesotho. Unpublished report.

Noar, S. (2006). A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: Where do we go from here? Journal of Health Communication, 11, 21-42.

Panos. (1999). AIDS reports: Investigating an epidemic. Report from Panos Institute South Asia. Panos-UNESCO publication. London:Panos

Panos. (2003). Missing the message? 20 years of learning from HIV/AIDS. London: Panos Institute UK.

Piot, P. (2000). Global AIDS epidemic: Time to turn the tide. Science, 288, 2176-2178.

Rogers, E.M. & Singhal, A. (2003). Combating AIDS: Communication strategies in action. New Delhi: Sage.

UNAIDS. (1999a). Sexual behaviour change for HIV: Where has theory taken us? UNAIDS Best Practice Collection. Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNAIDS. (1999b) Communications framework for HIV/AIDS – A new direction. A UNAIDS/ Penn State Project. Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNAIDS. (2000). Tools for evaluating HIV voluntary counselling and testing. Best Practice Collection. Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNAIDS. (2004). The media and HIV/AIDS: Making a difference. Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNAIDS. (2005). HIV-related stigma, discrimination and human rights violations. UNAIDS Best Practice Collection. Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNAIDS. (2006a). Report on the global AIDS epidemic: Executive summary of the report on the global AIDS epidemic, 2006. UNGASS & Toronto report. Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNAIDS. (2006b). UNAIDS action plan on intensifying HIV prevention 2006-2007. Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNDP. (2007). Fighting climate change: Human solidarity in a divided world. Human Development Report. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

United Nations. (2001). United Nations General Assembly special session on HIV/AIDS declaration of commitment. Goals set to be achieved by 2003-2005. New York: UN.

United Nations Childrens Fund. (2006). Women and children – the double dividend of gender equality. The state of the world’s children 2007. New York: UNICEF.

Weiser, S., Heisler, M., Leiter, K., Percy-De Korte, F., Tlou, S., Demonner, S., Phaladze, N., Bangsberg, D., & Iacopino, V. (2006). Routine HIV testing in Botswana: A population based study on attitudes, practices, and human rights concerns. PLoS Medicine, 3(7), e261.

WHO. (2005). Summary country profile for HIV/AIDS treatment scale up. Retrieved January 20 2008 from www.who.int/countries/lso/en/.

Wolfe, W.R., Weiser, S.D., Bangsberg, D.R., Thior, I.J., Makhema, M., Dickinson, B., Mompati, K.F. & Marlink, M.R. (2006). Effects of HIV-Related Stigma among an early sample of patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Botswana. AIDS Care, Vol. 18: 931-933.

World Bank. (1999). Intensifying action against HIV/AIDS in Africa – responding to a development crises. Retrieved from http://go.worldbank.org/QRWUPT6440.

World Bank. (2000a). Lesotho – the development impact of HIV/AIDS – selected issues and options. World Bank Macroeconomic Technical Group. Unpublished report.

World Bank. (2000b). World Development Report. Retrieved January 20 2008 from http://go.worldbank.org/Z2LU71DB90.

World Bank. (2003). Multisectoral HIV/AIDS projects in Africa: A social analysis perspective. Retrieved January 20 2008 from http://go.worldbank.org/Y2BJAG21L0.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply