After Victory, What Will Lula’s Foreign Policy Look Like?

The tenure of President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil is defined by the deforestation of the Amazon, the return of 33 million Brazilians to hunger, and the terrible governance of the country during the pandemic.

But it also marked a radical turning point on a subject that receives little public attention in general: foreign policy. It’s not just that the Bolsonaro government has transformed Brazil, a giant in land area and population, into a kind of diplomatic dwarf. Nor is it just the fact that Bolsonaro turned the country’s back to Latin America and Africa. The most serious thing is that in his pursuit of aligning Brazil to the United States, Bolsonaro broke with a long tradition of Brazilian foreign policy: the respect for constitutional principles of national independence, self-determination of the peoples, non-intervention, equality between States, defense of peace, and peaceful solution of conflicts.

Despite the different foreign policies adopted by Brazilian governments over the years, no president had ever so openly broken with these principles. Never had a Brazilian president expressed such open support for a candidate in a U.S. election, as Bolsonaro did to Trump and against Biden in 2020. Never had a president so openly despised Brazil’s main trading partner, as Bolsonaro did with China on different occasions. Never had a Brazilian president offended the wife of another president as Jair Bolsonaro, his Economy Minister Paulo Guedes, and his son Representative Eduardo Bolsonaro did in relation to Emmanuel Macron’s wife, Brigitte. And never, at least since re-democratization in the 1980s, has a president talked so openly about invading a neighboring country as Bolsonaro did toward Venezuela.

This attitude has thrown Brazil into a position of unprecedented diplomatic isolation for a country recognized for its absence of conflicts with other countries and its capacity for diplomatic mediation. As a result, during the campaign for the 2022 elections—won by Lula da Silva on Sunday, October 30, by a narrow margin of 2.1 million votes, with 50.9 percent of the votes for Lula against 49.1 percent for Bolsonaro—the topic of foreign policy appeared frequently, with Lula promising to resume Brazil’s leading role in international politics.

“We are lucky that the Chinese see Brazil as a historic entity, which will exist with or without Bolsonaro. Otherwise, the possibility of having had problems of various types would be great. … [For example, China] could simply not give us vaccines,” professor of economics at Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) Elias Jabbour tells me. “Brazil should once again play a decisive role in major international issues,” he adds.

The Return of ‘Active and Assertive’ Foreign Policy?

International relations during the first Lula administrations, from 2003 to 2011, were marked by Celso Amorim, minister of foreign affairs. He called for an “active and assertive” foreign policy. By “assertive,” Amorim meant a firmer attitude to refuse outside pressure and place Brazil’s interests on the international agenda. By “active,” he was referring to a decisive pursuit of Brazil’s interests. This view was “meant to not only defend certain positions, but also attract other countries to Brazil’s positions,” Amorim said.

This policy meant a commitment to Latin American integration, with the strengthening of Mercosur (also known as the Southern Common Market) and the creation of institutions such as Unasur, the South American Institute of Government in Health, the South American Defense Council, and CELAC. The IBSA forum (India, Brazil, and South Africa) and the BRICS bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) were also established. During this period, Brazil also advanced its relations with the European Union, Africa, and the Middle East. Due to Brazil’s size and the diplomatic weight it took on by increasing its diplomatic representation worldwide, Brazil came to be an important player in international forums, seeking to advance discussions toward multilateralism and greater democratization of these forums, effectively mediating sensitive issues such as the Iran nuclear agreement with the UN and tensions between Venezuela and the U.S. during the Bush administration.

So Far From God and So Close to the U.S.

There is a popular phrase throughout Latin America, originally said by Mexican General Porfirio Díaz, overthrown by the Mexican Revolution in 1911: “Poor Mexico! So far from God and so close to the United States.” It applies outside the bounds of its original time and place. Today’s Latin Americans could easily swap out “poor Mexico” for their own country, whether that’s Colombia, Guatemala, Argentina, or even Brazil—a country where a Christ the Redeemer statue is an international tourist attraction.

In a scenario where nations are heading toward war and confrontation, the return of a diplomatically active Brazil may be exactly what the world, and Latin America in particular, needs. “For the past 40 days, the war in Ukraine has been heading toward a point of no return. Diplomatic exits are no longer on the agenda and the use of brute military force has increased,” says Rose Martins, a doctoral candidate in international economic relations at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). “In this scenario, the BRICS and its New Development Bank offer alternatives for economic development distinct from the neoliberal terms.”

The question, perhaps, is which “world” actually looks forward to an active Brazil. This resumption may interest the Third World, for example, but there are doubts about whether it would interest the so-called Western world. “In this global situation, in which there is a dispute over ‘cosmotechnics’ and among which the exercise of force is in place, Brazil will have to play in a very balanced way, with great caution,” says Professor Héctor Luís Saint-Pierre, coordinator of the Defense and International Security Study Group (GEDES). “I can imagine two possible attitudes: from the point of view of the dispute over cosmotechnical hegemonies, it would be the pragmatic non-alignment. In other words, entering into commercial, economic, and technological relationships in a pragmatic way, non-aligned: neither with one nor with the other,” he says. “And with regard to the U.S., a certain precaution, because they are at war—we are not. We don’t need to go to war to defend U.S. interests: the right thing to do, to defend Brazilian interests, is not going to war. Sometimes national interests are defended by not going to war.”

In addition to the external challenge, Lula arrives at the presidency in a very different situation from that found in his first term. Not only will he have to deal with all the institutional destruction left by Jair Bolsonaro, but he will also have to deal with the members of his own “broad front” coalition—many of whom had been radical opponents during his previous governments. One of the most sensitive topics, however, is how the armed forces will act. Since the coup against Dilma Rousseff, in 2016, the generals have returned to the Brazilian political scene, expanding their domains to the point of conquering thousands of positions under Bolsonaro—a scenario that puts a country that only left its last military dictatorship 37 years ago on alert. “More than paradoxical, it is aporetic. It’s a dead-end situation,” says Saint-Pierre, when I ask him whether the way to disarm military power internally would be to carry out a consistent foreign policy, or if, in order to carry out a consistent foreign policy, it would first be necessary to disarm military power. He believes that Lula will have to establish some kind of pact with the military, in which their demands are respected, so that he can effectively govern. But for all the challenges, Saint-Pierre, Martins, and Jabbour all seem to agree on one point: the Lula government’s foreign policy will definitely be better for Brazil, Latin America, and the world than Bolsonaro’s. So do the Brazilian people.

This article was produced by Globetrotter in partnership with Revista Opera.

Pedro Marin is the editor-in-chief and founder of Revista Opera. Previously, he was a correspondent in Venezuela for Revista Opera and a columnist and international correspondent in Brazil for a German publication. He is the author of Golpe é Guerra—teses para enterrar 2016, on the impeachment of Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff, and coauthor of Carta no Coturno—A volta do Partido Fardado no Brasil, on the role of the military in Brazilian politics.

Source: Globetrotter

Indigenous Organizers In Alaska Lead The Way Toward Livable Climate Future

In the United States, the public and politicians are moving in opposite directions on climate change. Grassroots environmental activism is spreading on the local state, regional and national levels, while Congress generally continues with a “business-as-usual” approach, rejecting the foremost way to avoid the worst consequences of global warming: the Green New Deal.

While the Green New Deal remains aspirational in the U.S., it has been adopted by the European Union, and scores of countries around the world have committed to pursuing its goals.

Among the many organizations in the U.S. fighting for environmental sustainability and a just transition toward clean, renewable energy is Native Movement, an organization dedicated to building people power for transformative change and imagining a world without fossil fuels.

“There is no future at all with continued oil and gas extraction,” says Ruth Łchav’aya K’isen Miller, Native Movement’s climate justice director, in this exclusive interview for Truthout. “We must eliminate fossil fuel extraction now through a just transition that guarantees justice for workers and for the lands.”

Miller is a Dena’ina Athabascan and Ashkenazi Jewish woman. She works toward Indigenous rights advocacy and is a member of the Alaska Just Transition Collective and the Alaska Climate Alliance.

C.J. Polychroniou: Ruth, what does a just transition, from a Native and Indigenous perspective, look like in Alaska?

Ruth Miller: A just transition is a journey of returning to economies, governance structures and social contracts that are not new, but built on Indigenous wisdoms and place-based knowledge to create a truly regenerative economy. A just transition will be built on a values framework of anti-racism and decolonization, deep reciprocity, and respect for all lands, waters and air.

Any just transition for Alaska must be rooted in Indigenous perspectives, because it is Alaska’s Native nations who have lived in harmony with these lands for over 30,000 years, and whose deep connections, encyclopedic knowledge and spiritual interconnectivity will heal the wounds of the past 100 years of colonization and extractive capitalism. For this reason, we refer to this shift in resource extraction, governance, labor practices and culture as “remembering forward,” first translated in 2020 in the Behnti Kengaga language as “Kohtr’elneyh,” and in 2022 in the Dena’ina language as “Nughelnik.”

In Alaska this takes many forms. It includes deep democracy, which actively seeks to incorporate minority voices as well as those in the majority and requires the diversification of elected leaders. It includes an end to all oil and gas extraction, as well as irresponsible mining and other development projects. It means a return to responsible land management practices, including timber and fisheries management, and it means returning stewardship of lands and waters back to their original and eternal caretakers. It includes supporting Alaska Native language and cultural revitalizations while supporting unimpeachable subsistence hunting and fishing rights. It means all workers will have their fair pay and rights protected through strong unions, while communities will be empowered to support themselves through mutual aid networks and non-predatory community loan funds for moving toward clean and efficient energy.

A just transition for Alaska means investing in regenerative industries like sustainable mariculture and ocean-healing crops such as kelp, while also supporting culturally informed eco-tourism that elevates local business with local returns. As we have previously written for Non-Profit Quarterly, “To achieve [a Just Transition], resources must be acquired through regenerative practices, labor must be organized through voluntary cooperation and decolonial mindsets, culture must be based on caring and sacred relationships, and governance must reflect deep democracy and relocalization.”

Why is the complete elimination of fossil fuel extraction needed to secure a just transition?

The simple truth is that the oil and gas industry is one of the largest contributors to climate change, spewing greenhouse gas emissions to the point at which we are now in the sixth great extinction — one which has been entirely caused by recent human activity. The Arctic, being bled dry for its non-renewable resources, is now experiencing a climate crisis at two to four times the rate as the rest of the globe.

In Alaska, thawing permafrost is not only destabilizing Arctic infrastructure, but the thawing of eons-old organic material leads to the accelerated release of methane, a gas more than 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere. The same thawing is leading to coastal and riverbed erosion, causing more and more communities to be forced to relocate. Already less Arctic sea ice returns in the winter than past generations remember, putting coastal communities at increased risk of damage by winter storms.

With a global temperature rise of 2.5 degrees Celsius or higher (which we are projected to reach within the decade without drastic international action now), it is expected we will have an entirely ice-free Arctic Ocean at least once every eight years. Beyond their climate effects, extractive projects are already causing extreme and irreversible devastation to lands, waters and food systems.

The ecological harm caused by such projects leaves toxic waste, pollution and contamination, harming the health of Alaska Native peoples who live closest with the land. Near the sites of extractive projects, high rates of cancers, birth defects, respiratory illnesses, and more health impacts have been observed for decades. Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit relatives suffer increased rates of homicide, disappearance and domestic violence in and around the man camps that supply labor to extractive development projects.

There is no future at all with continued oil and gas extraction…. We must eliminate fossil fuel extraction now through a just transition that guarantees justice for workers and for the lands. Read more

Stopping The War In Ukraine Now Is The Only Option

It might not be ‘cool’ to lay down weapons now, but it would mean the end of senseless violence and prevent the annihilation of Ukraine.

Reuters estimates that, after three weeks of war, 14,000 people have been killed, 2,7 million people have fled, 1,700 buildings have been destroyed and damages exceed 110 billion euro. The trauma that will result from what is happening in Ukraine will last decades.

Defense budgets all over Europe are being increased and relationships with Russia will be disrupted for years to come.

Whenever there is fighting, we seem to be grabbed by a hunger for war: Nuances disappear and a choice must be made between good and evil. The complex reality doesn’t matter anymore, nor do the reasons for the conflict.

Language as a weapon

Language also becomes a weapon in times of war: “Those who do not support us militarily, want us to slowly die”, says Zelensky. It may sound logic, but it’s not true – nobody wants the Ukrainian people to slowly die.

The appeal is clear, however. If you care about us, you support us with weapons, whatever it takes. The Netherlands is also understanding of Zelensky’s call for Polish fighter jets and Finland’s wish to become a member of NATO. Both would be an extremely dangerous escalation.

Ukraine did not start this war, but every day Zelensky chooses to continue this inequal battle, he also bears responsibility for the death toll, the refugees and the destruction of his country.

A high price to pay

Continuing to fight maybe cool, but the people of Ukraine and soldiers on both sides are paying a terrible price. Putting weapons down might not be cool, but it would end the senseless violence and prevent the annihilation of Ukraine.

Even if it would cost him his life, ending the war would make Zelensky immortal, a true hero. Defending your country sounds noble, but what if the price is a completely destroyed country? With tens of thousands more dead and millions of refugees?

A report from the NOS Journaal (Dutch news report) sticks with me. A captured Russian soldier being interrogated somewhere in Ukraine. “How old are you?” Answer: 21 years old. “Where are you from?” From St Petersburg. “What are you doing here?” I was sent here. “What do you want?” I want to go home.

According to the voice-over the young man was later executed. Refusing to perform military service is incredibly difficult in both Russia and Ukraine. Soldiers do not have a choice, political leaders do. As Bob Dylan wrote in his song Masters of War in 1963: ‘You put a gun in my hand / And you hide from my eyes.’

Peaceful protest

War is terrible and the next violent outbursts are already announcing themselves: Moldavia, Georgia, the Baltic States, Taiwan. Will we push the world closer to the brink of war? I prefer to draw hope from the peaceful protest Gandhi used against the British rule in India, the kind that Martin Luther King used to end segregation in the United States, how mass protests around the world helped end the war in Vietnam and how peaceful protest from the East Germans brought down the Berlin Wall in 1989.

According to War Resisters’ International (WRI), an organization founded in 1921 to promote peace and antimilitarism, over 1,1 million Russians have signed a petition against the war started by Russian human rights activist Lev Ponomarev.

Yurii Sheliazhenko of the Ukrainian Pacifist Movement called for peaceful protest three days after the start of the war, where most people only see military solutions. He considers a neutral Ukraine the best option for the future.

The only option

They know that violence only begets violence, history is full of it. Pacifism is not a popular concept in times of war, but among the people who believed in it and practiced it were Jesus of Nazareth and Albert Einstein, John Lennon and Mother Theresa. Call them idealists, but the world would be a far worse place without them.

Stopping the war now is the only option. Does that mean Putin gets his way? No. If he wants to occupy all of Ukraine and succeeds, he inherits a country of 44 million dissidents. Even for a dictator, that is a nightmare.

Willem de Haan is a Dutch sociologist, conscientious objector and journalist. Go to: https://www.willemdehaan.nl

Original published in Leeuwarder Courant (Dutch daily), 03.19.2022

Translation: Sunny Resch

“Politics as Usual” Will Never Be A Solution To The Current Climate Threat

There is an ever-growing consensus that the climate crisis represents humanity’s greatest problem. Indeed, global warming is more than an environmental crisis — there are social, political, ethical and economic dimensions to it. Even the role of science should be exposed to critical inquiry when discussing the dimensions of the climate crisis, considering that technology bears such responsibility for bringing us to the brink of global disaster. This is the theme of my interview with renowned scholar Richard Falk.

For decades, Richard Falk has made immense contributions in the areas of international affairs and international law from what may be loosely defined as the humanist perspective, which makes a break with political realism and its emphasis on the nation-state and military power. He is professor emeritus of international law and practice at Princeton University, where he taught for nearly half a century, and currently chair of Global Law at Queen Mary University London, which has launched a new center for climate crime and justice; Falk is also the Olaf Palme Visiting Professor in Stockholm and Visiting Distinguished Professor at the Mediterranean Academy of Diplomatic Studies, University of Malta. In 2008, Falk was appointed as a United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967. He is the author of some 50 books, the most recent of which is a moving memoir, titled Public Intellectual: The Life of a Citizen Pilgrim (2021).

C.J. Polychroniou: The climate crisis is the greatest challenge of our time, but, so far, we seem to be losing the battle to avoid driving the planet to dangerous “tipping points.” Indeed, a climate apocalypse appears to be a rather distinct possibility given the current levels of climate inaction. Having said that, it is quite obvious that the climate crisis has more than one dimension. It is surely about the environment, but it is also about science, ethics, politics and economics. Let’s start with the relationship between science and the environment. Does science bear responsibility for global warming and the ensuing environmental breakdown, given the role that technologies have played in the modern age?

Richard Falk: I think science bears some responsibility for adopting the outlook that freedom of scientific inquiry takes precedence over considering the real-world consequences of scientific knowledge — the exemplary case being the process by which science and scientists contributed to the making of the nuclear bomb. In this instance, some of the most ethically inclined scientists and knowledge workers, above all, Albert Einstein, were contributors who later regretted their role. And, of course, the continuous post-Hiroshima developments of weaponry of mass destruction have enlisted leading biologists, chemists and physicists in their professional roles to produce ever more deadly weaponry, and there has been little scientific pushback.

With respect to the environmental breakdown that is highlighted by your question, the situation is more obscure. There were scientific warnings about a variety of potential catastrophic threats to ecological balance that go back to the early 1970s. These warnings were contested by reputable scientists until the end of the 20th century, but if the precautionary principle included in the Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment (1972) would have been implemented, then certainly scientists bore some responsibility for continuing to work toward more capital-efficient means of finding technological applications for oil, gas and coal. As with adverse health effects, post-Enlightenment beliefs that human progress depended on scientific knowledge inhibited regulation for the benefit of the public good. Only when civil society began to sound the alarm were certain adjustments made, although often insufficient in substance, deferring to private interests in profitability, and public interests in the enhancement of military capabilities and governmental control.

Overall, despite the climate change crisis, there remains a reluctance to hamper scientific “progress” by an insistence on respecting the carrying capacity of the Earth. Also, science and scientists have yet to relate the search for knowledge to the avoidance of ecologically dangerous technological applications, and even more so in relation to political and cultural activities. There is also the representational issue involving the selection of environmental guardians and their discretionary authority, if a more prudential approach were to be adopted.

The climate crisis also raises important ethical questions, although it is not clear from current efforts to tame global warming that many of the world’s governments take them seriously. Be that as it may, how should ethics inform the debate about global warming and environmental breakdown?

The most obvious ethical issues arise when deciding how to spread the economic burdens of regulating greenhouse gas emissions in ways that ensure an equitable distribution of costs within and among countries. The relevance of “climate justice” to relations among social classes and between rich and poor countries is contested and controversial. As the world continues to be organized along state-centric axes of authority and responsibility, ethical metrics are so delimited. Given the global nature of the challenges associated with global warming, this way of calculating climate justice and ethical accountability in political space is significantly dysfunctional.

Similar observations are relevant with respect to time. Although the idea of “responsibility to future generations” received some recognition at the UN, nothing tangible by way of implementation was done. Political elites, without exception, were fixed on short-term performance criteria, whether satisfying corporate shareholders or the voting public. The tyranny of the present in policy domains worked against implementing the laudatory ethical recognition of the claims of [future generations] to a healthy and materially sufficient future.

Taking account of the relevance of the past seems an ethical imperative that is neglected because it is seen as unfairly burdening the present for past injustices. For instance, reparations claims on behalf of victimized people, whether descendants of slavery or otherwise exploited peoples, rarely are satisfied, however ethically meritorious. There is one revealing exception: reparations imposed by the victorious powers in a war.

In the environmental domain, the past is very important to the allocation of responsibility for the atmospheric buildup of greenhouse gas emissions. Most Western countries are more responsible for global warming than the vast majority of the Global South, and many parts of Africa and the Middle East face the dual facts of minimal responsibility for global warming yet maximal vulnerability to its harmful effects.

These various ethical concerns are being forced onto the agendas of global conferences. This was evident at the 2021 COP-26 Glasgow Climate Summit under UN auspices. The intergovernmental response was disappointing, and reflected capitalist and geopolitical disregard of the ethical dimensions of the climate change challenge.

“Localization” Can Help Free the Planet From Neoliberal Globalization

Localization offers the means to return to a real and stable economy not based on speculation, exploitation and debt.

Is there a viable alternative to the economic, social, political and environmental problems stemming from globalization? How about “localization”? This is the antidote to globalization propounded by Helena Norberg-Hodge, founder and director of Local Futures, an organization focused on building a movement dedicated to environmental sustainability and social well-being by rejuvenating local economies. Norberg-Hodge is a pioneer of the new economy movement, which now has spread to all continents, and the convener of World Localization Day, which was endorsed by the likes of Noam Chomsky and the Dalai Lama. Norberg-Hodge is the author of several books and producer of the award-winning documentary, The Economics of Happiness.

In this interview, Norberg-Hodge discusses in detail why localization represents a strategic alternative to globalization and a way out of the climate conundrum, the ways through which localization challenges the spread of authoritarianism, and what a post-pandemic world might look like.

C.J. Polychroniou: The global neoliberal project, under way since the early 1980s following the so-called “free-market revolution” launched by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in the U.S. and U.K., respectively, has proven to be an unmitigated disaster on all fronts. Why does a shift toward economic localization, a movement which you have initiated on every continent of the world, represent a superior strategic alternative to the existing socioeconomic order, and how do we go about making this transition?

Helena Norberg-Hodge: The process of globalization with its disastrous effects is a consequence of governments systematically using taxes, subsidies and regulations to support global monopolies at the expense of place-based regional and local businesses and banks. This process has been going on in the name of supporting growth through free trade, but it has actually impoverished the majority, that has had to work harder and harder just to stay in place. Even nation states have become poorer, relative to the trillions of dollars circulating in the hands of global financial institutions and other transnational corporations. This has systematically corrupted virtually every avenue of knowledge, from schools to universities, from science to the media.

As a consequence, instead of questioning the role of the economic system in causing our multiple crises, people are led to blame themselves for not managing their lives well enough, for not being efficient enough, for not spending enough time with family and friends, etc., etc… In addition to feeling guilty, we often end up feeling isolated because the ever more fleeting and shallow nature of our social encounters with others fuels a show-off culture in which love and affirmation are sought through such superficial means as plastic surgery, designer clothes and Facebook likes. These are poor substitutes for genuine connection, and only heighten feelings of depression, loneliness and anxiety.

I see a shift toward economic localization as a powerful strategic alternative to neoliberal globalization for a number of reasons. For starters, the increasingly planetary supply chains and outsourcing endemic to corporate globalization are systematically making every region less materially secure (something that became starkly apparent during the COVID crisis) and enabling ecological and labor exploitation cost shifting such that feedback loops that could promote greater transparency and thus responsibility are severed. A recent study showed that one-fifth of global carbon emissions come from multinational corporations’ supply chains. Localization means getting out of the highly unstable and exploitative bubbles of speculation and debt, and back to the real economy — our interface with other people and the natural world. Local markets require a diversity of products, and therefore create incentives for more diversified and ecological production. In the realm of food, this means more diversified production with far less machinery and chemicals, more hands on the land, and therefore, more meaningful employment. It means dramatically reduced CO2 emissions, no need for plastic packaging, more space for wild biodiversity, more circulation of wealth within local communities, more face-to-face conversations between producers and consumers, and more flourishing cultures founded on genuine interdependence.

This is what I call the “solution-multiplier” effect of localization, and the pattern extends beyond our food systems. In the disconnected and over-specialized system of global monoculture, I have seen housing developments built with imported steel, plastic and concrete while the oak trees on-site are razed and turned into woodchips. In contrast, the shortening of distances structurally means more eyes per acre and more innovative use of available resources.

Mati Shemoelof – Opening Words – On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV, October 28, 2021, Goethe-Institut Amsterdam, Performance

28 October 2021, 20.00 pm, Performance and Meeting – Mati Shemoelof (Poet, Author, Editor, Journalist, Berlin) & Joseph Sassoon Semah

The discussion about the creative activities of Joseph Beuys adhere to Eurocentric culture in general and to post-war German culture in particular. And yet, what will happen when two Iraqi Jews, i.e. Babylonian Jews – who live in two European capitals, Berlin and Amsterdam, respectively – decided to deconstruct Beuys’ post war art production.

Could we give these two guests who became our host free speech, and should we listen to their desire to reclaim the Jewish Babylonian tradition from Joseph Beuys’ art?

Most of the research on Joseph Beuys artistic activity has been generated by theories concerning Eurocentric culture, values and experiences, however this time we have the opportunity to hear other voices, a different reading that criticizes Beuys’ work.

Mati Shemoelof – Opening Words 28.10.2021. Goethe Institut – Amsterdam

Joseph Sassoon Semah’s artistic work criticizes and unmasks the work of Joseph Beuys, the most influential German artist post WWII. In his criticism of Beuys’ art, Joseph Sassoon Semah uses the term “An Oppressive memory”. To my mind, he means how an oppressor performs/re-presents/re-disguises himself as a victim and by doing so, he silences the victim.

Beuys, the big shaman of German art, spoke of the famous LEGEND of how his airplane was shot down and that he was saved by the Tartars. This is a myth that he created in order to make us feel compassion for his deeds.

Let us first state the facts: In 1936 Beuys was a member of the Hitler Youth. We know that it was compulsory, but later on, in 1941, Beuys volunteered for the Luftwaffe (the aerial warfare branch of the Wehrmacht during World War II). In 1942, Beuys was stationed in Crimea and was a member of various combat bomber units. From 1943 on he was deployed as a rear-gunner in the Ju 87 “Stuka” dive-bomber. Initially stationed in Königgrätz, later on in the eastern Adriatic region. On March 16th 1944, Beuys’ plane crashed on the Crimean Front, close to Znamienka. Records state that Beuys was conscious and recovered by German search commandos. There were no Tatars in the village at that time however. Beuys was then brought to a military hospital where he stayed for three weeks from March 17th to April 7th.

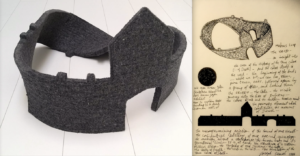

The research, texts, performances, art works and installations of Joseph Sassoon Semah today is a Babylonian Jewish de-construction of the artistic activities of Beuys from the center of Europe. In his artistic performance Joseph Sassoon Semah refers to two famous installations of Beuys. The first is the “Straßenbahnhaltestelle / Tram Stop” that was unveiled at the Venice Biennale of 1976. Joseph Beuys created a copy of a monument which was placed next to Tram Stop in Kleve – consisting of a field cannon crowned with a bust based on the figure of “Jean Baptiste Cloots”. Cloots was born in 1755 near Kleve, at the castle of Gnadenthal, and later called himself “Anachrsis Cloots”. He later joined the French revolution and symbolizes democracy.

Joseph Beuys’ Tram Stop in 1976 is in a matter of fact a memory of Beuys as a 5 year old kid waiting for the train that would take him to visit his uncle who lived in Kleve. Joseph Beuys explained that he used to cross the street and sit on the monument named by the city as the “Iron Man”; At a certain time, the field cannon was crowned with a cupid. So, the memory is love and the idea that democracy should be spread by the cannon, and not war.

In Kleve not so far from the tram stop, there was a Jewish synagogue that was destroyed by Nazi troops during Kristallnacht. And when you add the fact that Beuys himself was part of the Nazi air force you get a story of re-creating himself as a rebel figure. Meanwhile ignoring the authentic victim while re-presenting himself as a victim.

Joseph Sassoon Semah doesn’t forget Kleve’s synagogue, as well as the real actions of Beuys. He writes letters to Albrecht Dürer, another German artist, in order to penetrate the German and European cannon and to bring back the lost Jewish voice. He writes: “All in all, Jose[f]ph Beuys’ Straßenbahnhaltestelle / Tram Stop 1976 is physical – that is a real visible object in opposition – a manifestation to be contemplated from afar. The result of the intolerable conflict of false and true elements in Jose[f]ph Beuys’ ideology which he tried to expand – to escape as it were, from his impossibility, i.e. from his post-traumatic stress disorder into a symbolic Healer of post-war West Germany, and at the same time to foster its future reputation.”

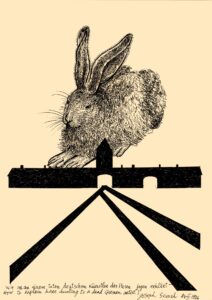

In another famous Artwork Beuys planted 7000 Oak trees throughout the city of Kassel – each tree accompanied with basalt stone – as part of the seventh Documenta in Kassel (1982). Joseph Beuys’ idea was to breath life back into the emptiness and rubble of 7000 bomb holes that were left bythe carpet bombing made by the allies in WW2.

Joseph Sassoon Semah refers to different theological resources – the Bible and the New Testament – in order to find the origins of meanings of the number 7000.

1 Kings: 19: 17-18 “17. And it shall come to pass, that him that escapeth the sword of Hazael shall Jehu slay: and him that escapeth from the sword of Jehu shall Elisha slay. 18. Yet I have left me 7000 seven thousand in Israel, all the knees which have not bowed unto Baal, and every mouth which hath not kissed him.”

And the New Testament – Romans 11:4 – “But what saith the answer of God unto him? I have reserved to myself 7000 seven thousand men, who have not bowed the knee to the image of Baal.”

Joseph Sassoon Semah uses these two resources in order to re-capture the real essence of the number 7000. He also uses an additional theological resource to capture the essence of The OAK and the Stone from the Old Testament – The Bible tells us about the OAK AND THE STONE – Joshua 24 :25-27: “On that day Joshua made a covenant for the people, and there at Shechem he established for them a statute and ordinance. recorded these things in the Book of the Law of God. Then he took a large stone and set it up there under the oak that was near the sanctuary of the LORD. And Joshua said to all the people, “You see this stone. It will be a witness against us, for it has heard all the words the LORD has spoken. To us, and it will be a witness against you if you ever deny your God.”

To summarize my ideas until now, I want to contextualize why we are doing the action of planting an OAK tree and placing it next to a Stone originated from Jerusalem. Joseph Sassoon Semah wants to create a real new covenant with God. Not the God of the scripture, but the spiritual one. He reclaims the Jewish symbols which Beuys appropriated, and recreates a new symbolic order on the land of Europe. It is both an artistic moment and a spiritual one, both happening here on the European ground.

Beuys refers to Kleve with nostalgia and at the same time forgets about the Kristallnacht and his own involvement in WW2; Beuys also refers to the bombing of KASEL and forgets that it took place in order to defeat NAZI troops and to stop the destruction of Jewish life. In his position Beuys appropriates the victim voice but Joseph Sassoon Semah reclaims it and re-creates a new alliance with God using the old meaning of the Oak tree and the stone here in the garden of Goethe Institute.

2.

Joseph Sassoon Semah’s de-construction of Beuys art is also another dialogue that he conducts as an Israeli Jew who emigrated to Europe.

In his artistic performances and installations, he criticizes the admiration of Israeli artists toward Beuys.

In his insightful article, Dr. Kobi ben Meir writes about “Joseph Beuys and the Cultural Effect of Israeli Art of the 1970s”. I will use some of his ideas in order to reflect upon Joseph Sassoon Semah’s sharp artistic and poetic response to the Israeli admiration of Beuys’ art.

At the art school of Bezalel, Beuys became a revered hero, and Israeli artists made a pilgrimage to his Studio in Düsseldorf. The known Israeli artist David Ginaton says that he first heard about the beginning of the Yom Kippur War as he was he travelling by train to Düsseldorf. As soon as they arrived in Düsseldorf on the second day of the war, on October 7th, 1973, Ginaton went to Joseph Beuys’ home. After ringing the doorbell of Beuys’ house, his wife opened the door and said that her husband was out of town for several days. Ginaton’s partner photographed him kneeling in front of the door of the Beuys’ house.

It is interesting to examine how Ginaton positions himself in front of the closed door of Beuys’ house. When it comes to size ratios, the young artist appears small in size and is almost disappearing in front of the massively large door. He kneels like an admirer of a holly person, and while he lowers himself, he is looking up as if at a holy past or a coveted hero. Ginaton kneels outside the door frame in a sense the frame represents the high German art world to which he can’t enter. Therefore, Ginaton has no choice but to admire in reverence. Dr. Kobi ben Meir concludes that this admiration is a sign of pagan fetishism.

If we go back to the first part of my interpretation of the artistic work of Joseph Sassoon Semah, we will find the real man behind Beuys. The soldier, the oppressor who manipulates through his myth in order to transform himself into the voice of the oppressed. When we observe the kneeling of Ginaton in frontof Beuys door – We get a distorted image.

How is it possible then that the Israeli Jewish artists, most of them second-generation Ashkenazi Jewish Holocaust survivors – are kneeling in front of Joseph Beuys and not the other way around?

Only 30 years after 1945 Beuys transformed himself into an extraordinary identity, which somehow forced them to forget about his real past actions.

David Ginaton testifies that through this photo and others he sought to clarify the relationship between Israeli art and international art, and to discuss questions of influence and appropriation.

In this photograph, the Israeli artist reveals himself as inferior to European art as part of a central and peripheral relationship, both influential and influenced.

In his artistic works Joseph Sassoon Semah removes the veil and de-mystifies this distorted identity. Joseph Sassoon Semah is both a European/Amsterdam Based artist and a post-Israeli one. In having this dual identity he raises critical questions directed at the backbone of German and European art (Dürer-Beuys) and at the same time directs his artistic critical gaze towards the Israeli Jewish field of art to which he belonged before leaving Israel. He questions the reasons for the admiration that borders on self-cancellation.

There are several answers I can give as a commentator concerning these distorted relationships of the Israeli art world towards the image of Joseph Beuys:

1. The Israeli militarism, subconsciously is being connected to the figure of the German soldier, in which the Israeli admiration towards the Israeli soldiers is evident.

2. The insult felt by the survivors of European descent from Europe. Yes, the same Europe that annihilated their families, became a phantasmatic desire to be accepted by them.

3. There is an element of an imagined return to the ethnic hierarchies that existed before World War II, in which European Germans were above all and Asians were inferior. That is, in perverted peripheral/center relations that recur in the minds of the Ginaton as a symptom to the positioning of the Israeli art in relation to the European art.

You can read it well in the famous Hannah Arendt‘s quote in a letter she wrote from Jerusalem in 1961, when she was attending the Eichmann trial. Her description of the crowd at the courthouse, in a letter she sent to Jaspers, passes beyond condescension into outright racism: “On top, the judges, the best of German Jewry. Below them, the prosecuting attorneys, Galicians, but still Europeans. Everything is organized by a police force that gives me the creeps, speaks only Hebrew, and looks Arabic. Some downright brutal types among them. They would obey any order. And outside the doors, the oriental mob, as if one were in Istanbul or some other half-Asiatic country.”

Joseph Sassoon Semah’s gaze is a DOUBLE gaze, it resembles the double face of Janus the god of Gates: On the one hand, he deconstructs and demystify the admiration of the Israeli artist to Joseph Beuys. On the other hand, his artistic work criticizing and unmasking the work of Joseph Beuys and the whole European cannon.

He also uses old Biblical knowledge (don’t forget that he is the grandson of the last Rabbi of Bagdad). So, his art is also a living traditional performance that is very much inspired by the Jewish tradition in order to re-present and re-perform a new artistic, social and political, spiritual and geographical order between his Babylonian Jewish point of view and his temporary place /HaMakom – both towards the German European art and the Israeli art.