ISSA Proceedings 1998 – The Renaissance Roots Of Perelman’s Rhetoric

Everyone here, I dare say, is aware of the stature of The New Rhetoric (as the Traité de l’argumentation came to be known in its English incarnation) has these days in the field of argumentation theory, of the elegance of Perelman’s critique of cartesian formalism, of his re-positioning of the question of what constitutes reasonability, and of the consequent enhancement – perhaps the rehabilitation – of a discipline that many found suspect: rhetoric. You are all no doubt aware as well of the sorts of reservations Perelman’s ideas have elicited, chiefly in the area of his notion of the “universal audience” or, indeed, of his radical audience-orientation in general. Of these I shall have nothing to say because my concern is a rather different one from those expressed in the vast majority of critical response to Perelman.

Everyone here, I dare say, is aware of the stature of The New Rhetoric (as the Traité de l’argumentation came to be known in its English incarnation) has these days in the field of argumentation theory, of the elegance of Perelman’s critique of cartesian formalism, of his re-positioning of the question of what constitutes reasonability, and of the consequent enhancement – perhaps the rehabilitation – of a discipline that many found suspect: rhetoric. You are all no doubt aware as well of the sorts of reservations Perelman’s ideas have elicited, chiefly in the area of his notion of the “universal audience” or, indeed, of his radical audience-orientation in general. Of these I shall have nothing to say because my concern is a rather different one from those expressed in the vast majority of critical response to Perelman.

Nothing I have seen in the critical literature pays much attention to two important subjects treated by Perelman in the Traité: loci and figures. I do not know why this is so. It may be that his interpreters of record understand these things better than I do. But it is nevertheless exceedingly strange that they should ignore them, since they constitute by far the greatest part of Perelman’s discussion. On the very face of it, therefore, a look at Perelman’s treatment of loci and figures seems very much in order. His book, he tells us in the very first pages, was to be a study of the discursive methods of “securing adherence”, methods that extend beyond the “perfectly unjustified and unwarranted limitation of the domain of action of our faculty of reasoning and proving” imposed by logic (p.3). His rhetoric is accordingly a method both of inquiry and of the means by which we can articulate the reasons for our decisions. The study of these discursive means centers on the loci of preference (NR pp.83-114/ TA 112-153) and schèmes argumentatifs (187-450/251-609) based on the loci (p.190/254f.), and on the verbal devices of eloquence in all its forms, devices ordinarily relegated to the realm of ornamentation and devalued as mere device (pp.167ff., 450f./ 225ff., 597f.). The primary subjects of the Traité are in short invention (not judgement, as so many want to claim) and expression.

Since time is short (and the argument is long), I will restrict myself to a brief examination of the resemblances between Perelman’s treatment of loci and Renaissance “place-logics” – particularly the place logic in the De inventione dialectica of the great Renaissance humanist, Rudolph Agricola. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – “I’m Just Saying…”: Discourse Markers Of Standpoint Continuity

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Group discussion of a controversial issue confronts participants with intellectual and pragmatic challenges that in practice are inextricably entwined. Argumentation theory attends primarily to the intellectual challenges and provides conceptual tools for analysis of issues and arguments. Practical argumentation, however, is fundamentally a pragmatic, communicative process. The pragmatic work of discussion is not merely a distraction from the intellectual work of argumentation. Rather, it sustains the social matrix within which argumentation becomes possible and meaningful as a constituent feature of certain collective activities.

To understand the normative and pragmatic dimensions of argumentation in their intertwined complexity requires empirical studies of practical argumentative discourse along with analytical and philosophical studies of normative argumentative (van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Jackson, & Jacobs 1993). The present study attempts to contribute to the empirical side of this inquiry by describing and analyzing certain uses of a particular pragmatic device.

Specifically, the paper reports a discourse analysis of discussions among students in an undergraduate “critical thinking” course. Student-led discussions of two controversial issues (capital punishment and legal recognition of homosexual marriages) were audiotaped and transcribed. Examining discourse markers (Schiffrin, 1987) in the two discussions, we noted frequent uses of “I’m just saying” and related metadiscursive expressions (I’m/we’re saying, I’m/we’re not saying, etc.). Our central claim is that these “saying” expressions are pragmatic devices by which speakers claim “all along” to have held a consistent argumentative standpoint, one that continues through the discussion unless changed for good reasons. Through microanalysis of a series of discourse examples (see Appendix B), in the following sections we show how these discourse markers are used to display continuity, deflect counterarguments, and acknowledge the force of counterarguments while preserving continuity. In a concluding section we reflect critically on the use of these continuity markers with regard to a range of argumentative and pragmatic functions that they potentially serve.

2. “Saying” as a Marker of Standpoint Continuity

Speakers often use “saying” as a discourse marker in order to highlight a formulation of their continuing standpoint in contrast to some other idea with which it might be confused. As in (1)19, the purpose may be simply to distinguish the speaker’s main point from a subordinate element such as evidence. Often, however, the purpose is to dissociate the speaker’s standpoint from some other, usually less acceptable, standpoint that in the context has been, or might plausibly be, attributed to the speaker. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Is Praise A Kind Of Advice?

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

In this paper, I will try to capture the fonction of the epideictic genre of the classical rhetoric from a linguistic point of view. This will be done by describing both praise and blame as peculiar varieties of “advices”.

2. Aristotle on epideictic

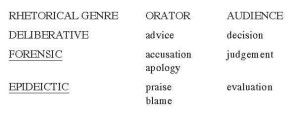

According to Aristotle, the object of rhetoric is a judgement that the audience should perform on the matter that is presented by the orator. Each of the three rhetorical genres – i.e. deliberative, forensic and epideictic – requires a specific discursive activity of the orator and a specific judgement of the audience. This typology can be summarized as follows:

In the light of this typology, one may observe that Aristotle’s statements remain rather vague about the activity performed by the audience of the epideictic genre. In the deliberative genre, the audience’s activity is a “decision”, i.e. some kind of deontic activity. In the forensic genre, the audience’s activity is a “judgement”, i.e. some kind of epistemic activity. But what about the “evaluation” which is supposed to be the audience’s activity in the epideictic genre? Aristotle, who seemed to be aware of this fuzziness, considered this “evaluation” as an aesthetical activity. Indeed, for him, the audience of the epideictic genre is in charge to judge the orator’s talent. But this way out endangers the internal coherence of the whole typology. In the deliberative and the forensic genres, the matter of the judgement reduces to the object of the discourse (the action (not) to be realized or the innocence/guilt of the defendant). On the contrary, the matter to be decided on by the audience of the epideictic genre is discourse itself.

3. Contemporary theories

Perelman rightly underlined the fact that although epideictic discourses – of praise or blame – have to do with matters that are not disputable (e.g. the greatness of the city, the authority of gods, the virtues of a dead person…), they nevertheless fulfil a function which is not merely aesthetical, since they are used to increase the communion of feelings concerning those values that are already endorsed by the whole community. In my opinion, Perelman implicitly referred to the ancient notion of homonoïa (i.e. concord, conformity, unanimity). As pointed out by Barbara Cassin, homonoïa is an effect created by discourse. In epideictic rhetoric, homonoïa could be seen as the emotion produced by amplification i.e. by the evocation of those prototypes of agents or actions that represent the values of the community. It should induce, in the mind of each citicitizen, a general disposition to some kind of political action. For example, Isocrates’ Panegyric, praises the city of Athens; this praise provokes a homonoïa effect which is such that Athenians citizens are inclined to accept, and to engage in, a war on the Persians.

This conception entails that there is an essential link between the epideictic genre and the deliberative one. Indeed, both aim at triggering a certain type of decision that should precede a certain type of action. This relationship had already been noticed by Greek and Latin authors. It is emphasized in Pernot’s book which directlyinspired me when choosing a title for this lecture: indeed, according to Pernot, praise is a kind of advice.

Pernot remarks that many discourses, like Isocrates’ Panegyric, belong to a hybrid genre, partly epideictic, partly deliberative. In other words, such texts are basically symbouleutic (from sumboulê: advice) – i.e. the orator supposedly performs a deliberative activity – but they are grounded on an encomiastic matter (from enkômion: praise), so that the orator should also perform an epideictic activity. According to Pernot, this is the typical case in which we can see that praise is a kind of advice. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Calculating Environmental Value: The Displacement Of Moral Argument

They took all the trees and put ‘em in a tree museum

They took all the trees and put ‘em in a tree museum

And they charged the people a dollar-and-a-half just to see ‘em

Joni Mitchell

“Big Yellow Taxi”

Rather, money endangers religion in that money can serve as universal symbol, the unitary ground of all action. And it endangers religion not in the dramatic, agonistic way of a “tempter,” but in its quiet, rational way as a substitute that performs its mediatory role more “efficiently,” more “parsimoniously,” with less “waste motion” as regards the religious or ritualistic conception of “works.”

Kenneth Burke

A Grammar of Motives

In May, 1997, Robert Costanza and a group of colleagues published in Nature the results of a meta-analysis of studies designed to measure the economic value of the environment. Perhaps due to the dramatic nature of their findings – they estimated the annual value of ecosystem functions and services at probably around $33 trillion in U.S. dollars compared to annual global gross national product of about $18 trillion – the report received considerable publicity, including coverage in the United States on National Public Radio and in the New York Times (Costanza, et al. 1997; Stevens 1997). Though the figures are stark, and probably startling to most, the fundamental argumentative strategy, the justification of environmentalism on purely economic grounds, a striking and controversial departure from traditional appeals for the defense of the environment, is part of a quietly growing trend. Kenneth Boulding, in the 1960s, called for such an accounting as a way to talk about the “throughput” of what he characterized as the “cowboy economy” (Boulding 1970: 97). Eric Freyfogle’s denominator is “free-market environmentalism,” and he identifies as its purpose “to structure resource-use decision making so that decisions respond, not to bureaucratic mandates, but to the more disciplined signals of the market” (Freyfogle 1998: 39). Costanza and his colleagues illustrate this purpose in the opening sentence of their report: “Because ecosystem services are not fully ‘captured’ in commercial markets or adequately quantified in terms comparable with economic services and manufactured capital, they are often given too little weight in policy decisions” (Costanza et al.1997: 253; sa Breslow 1970: 102-103).

The co-authors of the report in Nature, in their individual productions, represent a substantial voice on the academic side of this trend (Costanza et al. 1997: 260), but this is not arcane academic theory. Paul Hawken, co-founder of Smith and Hawken, makes precisely the same argument from a commercial perspective. “In order for a sustainable society to exist, every purchase must reflect or at least approximate its actual cost, not only the direct cost of production but also the costs to the air, water, and soil; the cost to future generations; the cost to worker health; the cost of waste, pollution, and toxicity” (Hawken 1993: 56). As for political manifestations of free-market environmentalism, Freyfogle points to the U.S. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Argumentation And Children’s Art: An Examination Of Children’s Responses To Art At The Dallas Museum Of Art

Until recently, relatively little attention has focused on the role of argument in the visual arts. In the last few years, however, and concurrent with the attention given to argument in other disciplines, argumentation scholars have begun to theorize about the intersection of argument and art. In 1996, a special edition of Argumentation and Advocacy examined visual argument, with essays that speculated about the argumentative functions in visual art and political advertisements. In their introductory essay to that special edition, David Birdsell and Leo Groarke write: In the process of developing a theory of visual argument, we will have to emphasize the frequent lucidity of visual meaning, the importance of visual context, the argumentative complexities raised by the notions of representation and resemblance, and the questions visual persuasion poses for the standard distinction between argument and persuasion. Coupled with respect for existing interdisciplinary literature on the visual, such an emphasis promises a much better account of verbal and visual argument which can better understand the complexities of both visual images and ordinary argument as they are so often intertwined in our increasingly visual media (Birdsell & Groarke 1996: 9-10).

Until recently, relatively little attention has focused on the role of argument in the visual arts. In the last few years, however, and concurrent with the attention given to argument in other disciplines, argumentation scholars have begun to theorize about the intersection of argument and art. In 1996, a special edition of Argumentation and Advocacy examined visual argument, with essays that speculated about the argumentative functions in visual art and political advertisements. In their introductory essay to that special edition, David Birdsell and Leo Groarke write: In the process of developing a theory of visual argument, we will have to emphasize the frequent lucidity of visual meaning, the importance of visual context, the argumentative complexities raised by the notions of representation and resemblance, and the questions visual persuasion poses for the standard distinction between argument and persuasion. Coupled with respect for existing interdisciplinary literature on the visual, such an emphasis promises a much better account of verbal and visual argument which can better understand the complexities of both visual images and ordinary argument as they are so often intertwined in our increasingly visual media (Birdsell & Groarke 1996: 9-10).

Although there is no consensus as to whether or not there should be a theory of visual argumentation, the attention given to the concept in this special issue merits further consideration.

The parallels between the fields of art and argumentation are striking. Both are concerned with the theoretical and the practical. Argumentation is concerned with the philosophical underpinnings of the making and interpreting of arguments, as well as the practical side of teaching the construction of arguments for others’ consumption. Art also must be concerned with the philosophy of the interpretation and construction of art works, as well as the practical and pedagogical aspects of teaching students to create art. Participants in both fields are also involved in the critical process, with the concomitant responsibility of speculating about the development of critical approaches and methodologies. Finally, and most relevant to this study, both are concerned with the realm of the symbolic.

In 1997, an exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art celebrated the role of animals in African Art. Particular works in this exhibition were supplemented with “imagination stations,” or sketchbooks with colored pencils, which allowed children to draw their reactions to this art. Children were guided by instructions developed by the education staff at the museum. These instructions asked the children to describe their reactions to the art and to put it into a context specific to their own backgrounds, such as asking the children to draw an animal that they were familiar with in a similar context to the one in the artwork. These sketchbooks were collected by museum staff, and provide the textual basis for this study. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Semantic Shifts In Argumentative Processes: A Step Beyond The ‘Fallacy Of Equivocation’

In naturally occuring argumentation, words which play a crucial role in the argument often acquire different meanings on subsequent occasions of use. Traditionally, such semantic shifts have been dealt with by the “fallacy of equivocation”. In my paper, I would like to show that there is considerably more to semantic shifts during arguments than their potentially being fallacious. Based on an analysis of a debate on environmental policy, I will argue that shifts in meaning are produced by a principle I call ‘local semantic elaboration’. I will go on to show that semantic shifts in the meaning of a word, the position advocated by a party, and the questions that the parties raise during an argumentative process are neatly tailored to one another, but can be incommensurable to the opponent’s views. Semantic shifts thus may have a dissociative impact on a critical discussion. By linking the structure of argumentation to its pragmatics, however, it may be revealed that there are two practices that account for a higher order of coherence of the debate. The first practice is a general preference for disagreeing with the opponent, the second practice is the interpretation of local speech acts in terms of an overall ideological stance that is attributed to the speaker. Because of these practices, parties do not criticize divergent semantic conceptions as disruptive, but they treat them as characteristic and sometimes even metonymic reflections of the parties’ positions.

In naturally occuring argumentation, words which play a crucial role in the argument often acquire different meanings on subsequent occasions of use. Traditionally, such semantic shifts have been dealt with by the “fallacy of equivocation”. In my paper, I would like to show that there is considerably more to semantic shifts during arguments than their potentially being fallacious. Based on an analysis of a debate on environmental policy, I will argue that shifts in meaning are produced by a principle I call ‘local semantic elaboration’. I will go on to show that semantic shifts in the meaning of a word, the position advocated by a party, and the questions that the parties raise during an argumentative process are neatly tailored to one another, but can be incommensurable to the opponent’s views. Semantic shifts thus may have a dissociative impact on a critical discussion. By linking the structure of argumentation to its pragmatics, however, it may be revealed that there are two practices that account for a higher order of coherence of the debate. The first practice is a general preference for disagreeing with the opponent, the second practice is the interpretation of local speech acts in terms of an overall ideological stance that is attributed to the speaker. Because of these practices, parties do not criticize divergent semantic conceptions as disruptive, but they treat them as characteristic and sometimes even metonymic reflections of the parties’ positions.

1. The fallacy of equivocation

Starting with Aristotle’s fallacies dependent on language (Aristotle 1955: 165 b 23ff.), the impact of shifts in the meaning of words on the validity of arguments has been a standard topic in the study of fallacies (as a review, see Walton 1996). Traditionally, such shifts have been dealt with by the ‘fallacy of equivocation’. We can say that a fallacy of equivocation occurs, if the same expression is used or presupposed in different senses in one single argument, and if the argument is invalid because of this multiplicity of senses. Moreover, in order to be a fallacy, the argument must appear to be valid at a first glance, or, at least, it has to be presented as a valid argument by a party in a critical discussion. Equivocation can be produced by different kinds of semantic shifts, for example, switching from literal to metaphorical meaning, using homonyms, confounding a type-reading and a token-reading, using the same relative term with respect to different standards (see Powers 1995, Walton 1996).

Like many others, Woods and Walton (1989) analyze equivocation as a fallacy in which several arguments are put forward instead of one. If the ambiguous term occurs twice, then there is at least one argument in which the ambiguous term is interpreted in an univocal way, and there is at least one other argument in which it is interpreted differently. Each of these arguments is invalid: The first argument is invalid, because in one of its assertions, the ambiguous term must be disambiguated in an implausible way to yield a deductively valid argument; the second argument is unsound, because it is deductively invalid. So, analytically, the fallacy of equivocation can be viewed as a conflation of several arguments. In practice, however, this ‘several arguments’ view seems to be very implausible. Woods and Walton posit that people reduce the cognitive dissonance that resulted from being faced with invalidating readings of the argument by conflating them into one that is seemingly acceptable. This “psychological explanation” for the “contextual shift”, that allows for two different readings of the equivocal term to occur in one argument (see Woods & Walton 1989: 198ff.), is not convincing. First, there is no reason why a person should generally be disposed to accept the argument in order to reduce cognitive dissonance – why doesn’t she simply reject it, if she discovers the fallacy? Secondly, most textbook examples of equivocation are puns or trivial jokes. Their humourous effect is founded on the incongruence between the plausible, default reading of the potentially equivocal expression on its first occasion of use and the divergent disambiguation it has to receive on its second occasion, if it is to make sense (Attardo 1994). That is, people just do not develop alternative readings, which they afterwards conflate, but they restrict themselves to contextually plausible readings.[i] It seems then that it is not a conflation of several arguments that leads to the acceptance of an equivocation. I suggest that it is simply the identity of the form of an expression that can be misleading, because it can erroneously suggest the identity of meanings, as long as there is no definite semantic evidence which points to the contrary. This view is in line with the observation that gross equivocations -for instance those that rest on homonyms which share no contextually relevant semantic features (like “bank”)- are easily discovered, while in the case of subtler equivocations, people often “feel” that there’s something fishy about the argument without being able to locate the trouble precisely. Read more