Fashola Replies Amnesty International, To Build 1,008 Flats In Badia

www.channelstv.com. August 12, 2013. The Lagos state governor, Babatunde Fasola, in a counter response to allegations made by Amnesty International has refuted claims that his administration is displacing some residents by pulling down their buildings.

A report by the organisation stated that an estimated 9,000 residents of Badia East lost their homes or livelihoods. However senior officials in the Lagos state government had claimed that the area was a rubbish dump.

According to Oluwatosin Popoola who is Amnesty International’s Nigeria researcher, “The effects of February’s forced eviction have been devastating for the Badia East community where dozens are still sleeping out in the open or under a nearby bridge exposed to rain, mosquitoes and at risk of physical attack”.

However, Governor Fashola countered Amnesty’s allegation that the government’s plan is to solve problems and ensure better living for residents. “That is why I have committed to build 1,008 flats in Badiya, to take people out of living on the refuse heap.”

Read more: http://www.channelstv.com/fashola-replies-amnesty-international

The Housing Crisis

Amandla.org. August, 12, 2013

As demonstrated in these pages the housing crisis is complex and multi-layered and cannot be separated from the wider social malaise facing South Africa. The causes of this crisis include policy confusion, market-based mechanisms for service provision, and the conception of ‘word-class cities’ as the ultimate goal of urban planners.

It should be noted that the housing crisis is not unique to South Africa. A similar phenomenon can be found across the developing world, from Brazil to India. Millions are flocking to the growing megacities in search of a better future as neoliberal policies force peasants off their land to make way for new mining projects and small-scale farmers are forced to compete with large-scale agribusiness from the EU or the US.

The cost of the neoliberal vision of the ‘world-class city’ is the emergence of new human dumping grounds in South Africa, termed ‘temporary relocation areas’ (TRAs). The most infamous of these is Blikkiesdorp, in Delft, Cape Town. Many of those evicted due to gentrification in such neighbourhoods as Woodstock, or because of decisions to ‘clean up’ the city for tourists for the 2010 World Cup, are dumped into these areas, supposedly for a short period. But, as any Blikkiesdorp resident will tell you, nobody seems to be moving out of these areas and into brand new RDP houses.

Read more: http://www.amandla.org.za/the-housing-crisis

Lejone John Ntema – Self-Help Housing In South Africa: Paradigms, Policy And Practice

Although the role of the state in housing provision in developing countries has varied considerably since World War II, Harris (1998; 2003) asserts that the state has, in general, continued to play a significant role in the provision of low-income housing. In turn, the role of the state – as embodied in its various policies, paradigms and practices – has become the subject of debate among academics, scholars, researchers and policy makers. Despite the fact that self-help housing is as old as humankind itself (Pugh, 2001), and that it was practised in different parts of the world before World War II (Harms, 1992; Harris, 2003; Parnell & Hart, 1999; Ward, 1982), it has since received varied institutional backing (Harris, 2003) and even more prominently since the early 1970s because of the World Bank’s influence in this regard (Pugh, 1992). From literature it is evident that one can distinguish between three different forms of self-help, namely laissez-faire self-help (virtually without any state involvement),

state aided self-help (site-and-services schemes) and institutionalised self-help (cases where the state actively supports self-help through housing institutions) (more detailed definitions follow in Section 1.1.2). Various forms of self-help housing have long been one of the most prevalent housing options in the world since World War II (see for example Dingle, 1999; Harris, 1998; Ward, 1982). The theoretical notion of self-help in the context of developing countries is commonly attributed to JFC Turner (Turner, 1976). Yet, it should be admitted that aided self-help in particular was both lobbied for, and practised, long before the rise of Turner’s ideas in the 1960s and 1970s (see Harris, 1998; 1999b). Furthermore, Turner’s

work, along with its practical consequences, is closely associated with the site-and-services and neo-liberal policies promoted by the World Bank (Pugh, 1992).

PhD-thesis University of the Free State, Bloemfontein: http://etd.uovs.ac.za/NtemaLJ.pdf

Blaise Dobson & Jean-Pierre Roux – Opportunities in Urban Informality, Development And Climate Resilience In African Cities

cdkn.org. Blaise Dobson and Jean-Pierre Roux (SouthSouthNorth) argue that African urbanisation and burgeoning informal settlements present an opportunity to build truly adaptive cities.

African cities are characterised by high levels of slums and informal settlements, largely informal economies, high levels of unemployment, majority youthful populations, and low levels of industrialisation. They have the highest growth rates in the world despite the fact that sub-Saharan Africa is still only approximately 40% urbanised. The urban poor, who largely reside in informal settlements and slums, are vulnerable to a range of global change effects, including global economic and climate change impacts. These can combine to have devastating effects on the poor, who generally survive on less than US$ 2 per day, but also on the ‘floating middle class’, who are defined as living on between US$ 2 – 4 per day, and constitute 60% of the African middle class.

The African Centre for Cities (ACC) and Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) hosted a three-day workshop in Cape Town in July aimed at developing a framework for understanding the intersection between climate resilience and urban informality, and promoting integrated urban development and management within African cities. ‘Champion groups’ from Accra (Ghana), Kampala (Uganda) and Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), which included local authorities, academia and civil society attended.

http://cdkn.org/opportunities-african-cities/

Natalia Ojewska – Ghana’s Old Fadama Slum: “We Want to Live in Dignity”

thinkafricapress.com. August 7, 2013. “On the outskirts of Accra, alongside the Odaw River and the Korle Lagoon, lies the slum of Old Fadama. Pejoratively referred to by many Ghanaians as a modern day “Sodom and Gomorrah”, Old Fadama is said to be home to around people, making it Ghana’s biggest slum.

Life here can be precarious and opportunities for social mobility are few and far between. Made up of a bustling, roughshod tessellation of closely built wooden structures, up to twenty people sleep on the floors of its individual ‘kiosks’ – each one an average of 3-4m2. Social amenities such as sanitation, running water, medical care and waste collection are hard to come by.

Read more: http://www.thinkafricapress.com/old-fadama-slum

Moladi – Imagination For People – Social Innovation For The Bottom Of The Pyramid

designmind. August 2013. About the project

designmind. August 2013. About the project

The aim of empowering people at the Bottom of the Pyramid is to identify appropriate technical solutions in order to tackle basic needs in developing countries. But what are basic needs exactly?

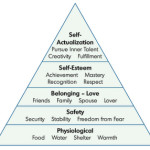

In 1943, Abraham Maslow presented his well-known “hierarchy of needs”. According to his theory, people need food, water, sleep and warmth the most. These are considered to be basic needs and it is only when these basic physical requirements are met that individuals can progress to the next level, that of safety and security. Once these needs are fulfilled, interpersonal needs such as love and friendship, as well as the need for self-esteem and respect from others, can gain importance. Self-fulfilment and the realization of one’s own potential represent the top of the hierarchy.

What does Maslow tell us? Food, sanitation and shelter are not only mandatory preconditions for survival – they also lay the foundations for the personal development of an individual. People can only grow and develop if they don’t suffer from basic supply problems: Children in school simply cannot learn on an empty stomach and the social and economic development of communities depends on access to safe water and sanitation services.

Today, the basic needs approach has become an integral part of theories about human motivation, social and economic development, particularly in the context of development in low income countries. It has become one of the major approaches to the measurement of what is believed to be an eradicable level of poverty and it also forms the center of people-focused development strategies. The “basic needs strategy in development planning” by the ILO (1976), for instance, calls for giving priority to meeting minimum human needs, providing certain essential public services, and also stresses the importance of citizen participation in the determination and tackling of needs. Citizen participation, economic growth, globalization and technology are all intertwined in these development approaches.

The definition of basic needs within the framework of empowering people therefore also encompasses food, water, shelter (moladi), sanitation, education and healthcare. The use of technology in concert with social entrepreneurship to improve the quality of life and social structures.

Read more: http://www.designmind.co.za/for-the-bottom-of-the-pyramid