The Nigerian-Biafran War

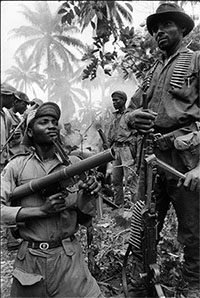

May 30 2017 marks the 50th birthday of the declaration of independence of the republic of Biafra, leading up to a 30-month civil war between federal Nigerian troops and the (Igbo) secessionists. On the occasion of this anniversary, the Library, Documentation and Information Department at the African Studies Centre in Leiden (ASCL) has compiled a web dossier on the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), also known as the Biafran War.

May 30 2017 marks the 50th birthday of the declaration of independence of the republic of Biafra, leading up to a 30-month civil war between federal Nigerian troops and the (Igbo) secessionists. On the occasion of this anniversary, the Library, Documentation and Information Department at the African Studies Centre in Leiden (ASCL) has compiled a web dossier on the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), also known as the Biafran War.

Far from being an exhaustive or even representative overview of the record of scholarship that has appeared on this topic, this dossier is an attempt to highlight different discourses reflected in the ASCL Library’s collection. After the introduction, section 2 presents a selection of publications on the war, ranging from a 1967 propaganda leaflet by the Nigerian government of information (Unity in Diversity) to a 2016 article on ‘the tensions in Nigeria-Biafra war discourses’. A highlight of this section is a collection of student essays on the civil war written in 1971 at the Toro teacher’s college. The cahiers were donated by their teacher, Aart Rietveld. Noteworthy is also the civil war chapters in the textbook series on civics and history for primary schools.

The third section deals with fictional accounts, personal narratives and poetry on the Biafran conflict, illustrating how much more literature there is than the (rightly famous) writings of Ken Saro-Wiwa, Adichie and Achebe.

Sections 4,5 and 6 capture the conflict through the biographical lenses of key actors. Writings by and about the two political protagonists, General Gowon (Nigerian head of state 1966–1975) and General Ojukwu (president of Biafra 1967–1971), give an insight into the federal and Igbo perspectives of the conflict. The third person chosen for this biographical section is the Yoruba nationalist Obafemi Awolowo, who was active as Federal Commissioner for Finance in Gowon’s cabinet during the war. Chinua Achebe portrays Awolowo as the architect of the starvation policy meant to crush the Igbo defence: “It is my impression that Chief Obafemi Awolowo was driven by an overriding ambition for power, for himself in particular and for the advancement of his Yoruba people in general. […] In the Biafran case it meant hatching up a diabolical policy to reduce the numbers of his enemies significantly through starvation […].”(There was a country, p. 233). This view contrasts strongly with the almost hagiographic accounts of “the man of courage , wisdom, reason and vision” (according to Moses Makinde).

The dossier is concluded with a selection of web resources and is introduced by former LeidenASA fellow Jays Julius-Adeoye, who recently published ‘The Nigeria-Biafra war, popular culture and agitation for sovereignty of Biafra nation’ in the ASCL working paper series.

Digital Engagement In A Post-Factual World: Silos, Echo-Chambers And Lies

What is communication?

What is communication?

What constitutes communication has always been historically contingent. It is never easy to pin down and designate ‘what is communication is’ and ‘what it is not’. But it is obvious that communication has taken many forms and evolved: from cave art to town criers, from street theatre to newspapers and television, and finally to digital engagement. One may argue that none of the aforementioned has influenced the world as much as digital engagement, making information available at your fingertips, changing the power dynamics for communicators, and transforming the way people can be influenced and their attitudes shaped. Here we try to explore issues of how digital engagement will thrive in a cynical, nationalist, populist world and raise the pertinent question: Does digital engagement encourage better decision-making, or merely reinforce prejudice?

The impact of Brexit and the USA presidential election

Two major events that gave “post truth” a linguistic footing were Brexit and the election of USA President Donald Trump. They showed that the world has indeed changed, and exposed the fact that people are making decisions based on emotions and beliefs. So, in the new world we live in, is evidence less important than beliefs? In the UK referendum on the EU, the #leave campaign claimed falsely that leaving the EU would mean that £350 million could be given to the National Health Service (NHS). After Brexit, thousands of people signed online petitions to have the result of the referendum reviewed. Gillian Tett, author of ‘The Silo Effect’ wrote, “The Brexit vote was decided on the basis of emotion – and the Remain camp failed to give voters a really positive vision of Europe.”

The impact of digital engagement on decision-making

Digital engagement was meant to make information more accessible to more people. But it has also made it possible for anyone to publish anything they want without having to provide evidence. As a result people find it hard to tell the difference between truth and lies. Fake news propagated on Facebook about the Pope supporting Trump and Trump’s tweets changing the direction of media coverage, makes one wonder whether digital engagement is encouraging propaganda and disinformation? Or whether people are making decisions based on emotions and do not care much about the facts?

In an interview with the Financial Times in June 2016 Adair Turner former Head of the Financial Services Agency (FSA) said, “I was once a confident optimist and rationalist. I also used to believe that everybody could be persuaded by rational argument. I’ve increasingly realised that people need mythologies, people need nationalisms and people need religions.”

Power to the powerless?

Digital engagement was thought to level the playing field and give power to the powerless (as in Arab Spring). It was believed to be a way to re-engage voters, in particular young people, with politics, giving a voice to the voiceless. Instead, it has given the powerful another weapon to acquire even more power. It favours those who shout loudest, responsible for the growth of ‘populism’ and government by Twitter. Today, anyone with a smartphone can voice an opinion, create an opinion train and broadcast beliefs. Communication becomes a political process when this happens, as opinion formation and counter-commonsensical visions gain popularity and contribute to undermining democracy. Perhaps this may have inspired the OECD, which has recently called on schools to teach young people how to identify fake news. Read more

- Page 3 of 3

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3