For Him Art, Research, Creation And Politics Were The Same Thing – In Memory Of Paul Boccara

Face à l’ énorme complexité des ces questions, il es urgent d’y aller, au risque d’essuyer les plâtres, des se tromper ; car il y a une béance formidable, et un appel!

Paul Boccara ended with these words the ‘Nine Lessons of Systemic Anthroponomy’. They can be seen as legacy of a great thinker. He was born in Tunis in 1932 – he finally left us on November 26 th 2017. Although he became entirely French in his attitudes, this Mediterranean origin shaped his way of thinking in a peculiar way. I remember one of our meetings in Ivry, where he lived; we went for lunch and there was no hesitation in choosing a seat. “I’m from

Tunisia – I need light,” and so we settled right next to the window. This urge to light was guiding his life, in a metaphorical sense: it was the strive for enlightenment. This was about a very bright light, illuminating the entire socio-historical space and at the same time it was the spotlight, which made it possible to take a close look at details.

Paul Boccara was educated as economist and mastered the tiresome depths of the bourgeois profession as well as the peaks of political economics. The latter was never a flattened shortcut for complex socio-historical constellations. It was only through knowledge of complex relationalities possible to achieve a truly creative application – a Marxist approach in the best possible sense. His profound thinking was also characterised by the fact that he studied in addition to economics also history and anthropology.

Three outstanding works have to be mentioned:

The Études sur le capitalisme monopoliste d’ État, sa crise et son issue [Éditions sociales, 1973] were probably part of the compulsory reading of the left at that time. Boccara’s work was ground-breaking, but at the same time it was part of a wider discourse concerned with the changing role of the state. This has to be understood against the historical background: on the one hand, at least throughout Europe, the ‘special conditions’ of the post WWII period came to an end and the West had to settle down with a consolidating East-West relationship.

What existed as a socialist state and their coalition could not be met by capital alone – if the state would not have existed already, it would have been invented at that time to complement and consolidate the hegemonic claims of the monopoly capital. In fact, such a re-invention of the string state took place in the sense of a close, organic interweaving of economy and state.

The Théories sur les crises, la suraccumulation et la dévalorisation du capital [Delga, 2013/2015] are nearly a late work. Hardly perceived, unfortunately not translated so far, the two volumes show the misery of the economy and of economics. It is noteworthy that the current crisis is analysed in a very fundamental way as a fundamentally structural crisis. Boccara’s oevre goes beyond other works, because it makes use of the very basics of economic theory: accumulation, theory of value, production and consumption, the long waves and the differentiated consideration of predator, casino and profit of capitalist economy are analysed in principle and assessed in connection with the techno-economic processes [‘information technologies of new type’].

Neuf Leçons sur l’ anthroponomie systémique [Delga, 2017], the last book, which is the assets we inherit – and the appeal, an urgent call obliging us to concrete and detailed analysis. Importantly Boccara emphasises the role of anthroponomy – these questions occupied him intensively in recent years. This is refreshingly different from many ‘identity and value discussions’ also in the left.

Strengthening the left can barely rely on hoping for insight into the necessity of a different way of life – questions of faith and pure good will and related hopes should be left to religion. Boccara, on the other hand, puts forward a clear analysis of the interplay between politics and economy and society. And it is not an appeal for such a way of life, but rather an appeal to a culture of debate. Read more

The Economist ~ Why “Affordable Housing” In Africa Is Rarely Affordable

ETHIOPIA’S flagship social-housing programme is probably the most ambitious in Africa. But for most locals the houses are still barely affordable. The poor cannot afford the down payment for even the most subsidised units. And those who can often struggle to meet repayments, opting instead to rent out the houses and move elsewhere. In this respect, though, Ethiopia is hardly alone in Africa. Take Angola, where a recent $3.5bn social-housing project on the outskirts of Luanda, the capital, offered apartments from $84,000, in a country where incomes per person are just over $4,000. Or Cameroon, where the government’s social-housing scheme is out of reach to 80% of the population, according to the World Bank. In Ethiopia the state has spent over a decade building cheap homes on an almost unprecedented scale, but supply still fails to match demand. Why?

Read more: https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/

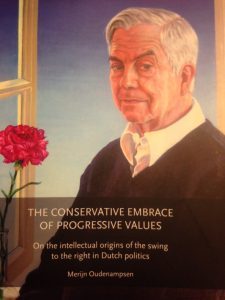

Merijn Oudenampsen ~ The Conservative Embrace Of Progressive Values. On The Intellectual Origins Of The Swing To The Right In Dutch Politics

To talk of ideology in the Netherlands is to court controversy. The Dutch are not exceptional in that sense. Ideology is known internationally to have a bad reputation. After all, the word first came into common use when it was employed by Napoleon as a swearword. But the Dutch distaste for ideology seems to have taken on particularly sharp features. The country lacks a prominent tradition of political theory and political ideology research and often perceives itself as having achieved the end of ideology. Taking recourse to Mannheim’s sociology of ideas, I have attempted to contest that image and fill a small part of the lacuna of Dutch ideology studies. The book started out with an attempt to formulate – in broad strokes – an explanation for the peculiarly apolitical atmosphere in Dutch intellectual life.

To talk of ideology in the Netherlands is to court controversy. The Dutch are not exceptional in that sense. Ideology is known internationally to have a bad reputation. After all, the word first came into common use when it was employed by Napoleon as a swearword. But the Dutch distaste for ideology seems to have taken on particularly sharp features. The country lacks a prominent tradition of political theory and political ideology research and often perceives itself as having achieved the end of ideology. Taking recourse to Mannheim’s sociology of ideas, I have attempted to contest that image and fill a small part of the lacuna of Dutch ideology studies. The book started out with an attempt to formulate – in broad strokes – an explanation for the peculiarly apolitical atmosphere in Dutch intellectual life.

The relative absence of ideological thought in the Netherlands, I have argued, can be traced back to the historical dominance of one particular form of ideological thought: an organicist doctrine that considers Dutch society as a differentiated, historically grown, organic whole. It considers the state and the media as the passive reflection of societal developments, with elites serving as conduits. Organicism is a sceptical, relativist ideology that stresses harmony and historical continuity. Shared by the twentieth-century elites of the different currents in the Netherlands, this ideology has been depicted as the metaphorical roof uniting the different pillars. It has filtered through Dutch intellectual history in complex forms, to emerge in more contemporary manifestations such as Lijphart’s pluralist theory of accommodation.

The thesis of this book is that this has resulted in a lingering tendency in the literature to downplay conflict, rupture and ideology in Dutch history. And instead to favour more harmonious portrayals of Dutch society developing gradually and continuously as a unity, as an organic whole. When it comes to the Fortuyn revolt, a similar inclination has resulted in depoliticized interpretations of the revolt as the exclusive imprint of secular trends that Dutch politics and media simply needed to reflect. Hans Daalder, the doyen of Dutch political science, argued that there is a political incentive to depoliticize matters in the Dutch political system. In the context of the close relationship between politics and social science in the Netherlands, this has given rise to a paradoxical reality: the more politically involved social science becomes, the more depoliticized it needs to become. Ironically, this means that a more autonomous social science will need to repoliticize its account of Dutch political transformation to some degree. That is what this study has sought to do.

See: https://pure.uvt.nl/Oudenampsen_Conservative.pdf

Joseph Sassoon Semah, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam ~ Statement 20 oktober 2017

Dames en heren, dank voor uw aandacht, ik ben een heel klein beetje medeplichtig aan het ontstaan van deze avond en Margriet Schavemaker was zo attent me te vragen die achtergrond toe te lichten. In 10 minuten ga ik dat doen (of 9 1/2 ).

Toen ik enkele jaren geleden mijn eerste werk van Joseph zag, was ik in het gezelschap van een vermaard kunstkenner met grote mond, een vriend die ik nu X ga noemen.

We stonden op een tentoonstelling en ik zag… wat was het?.. bladpapier met notenbalken… een omtrek van een liggende hond? De vorm van een hut? Wat, waarom en hoe: ik zag het niet precies, maar ik dacht: hé, dát vind ik mooi! Wat een eigenzinnige wereld.

Dat mooi slikte ik nét op tijd in. Kunstkenner X had me immers geleerd: échte kunst, vinden wij niet mooi, echte kunst, vinden wij goed. Dat je iets ook nog mooi kan vinden, is volkomen onbelangrijk, oftewel: oninteressant.

Dit fascineert me: het lukt me nooit om naar eigen tevredenheid uit te leggen waarom ik een kunstwerk mooi vind. Het werk van Joseph trok me aan, zonder dat ik kennis had van de achtergrond en referenties. Ik stamelde wat over scherp pikzwart op verkleurd papier, zo wonderlijk een huisje onder een tafel geplakt en ik probeerde mijn onkunde beschaafd te maskeren door wat te mompelen over hoe interessant het opduiken van het motief van de herhaling was, misschien zei ik bij een installatie met hout en metaal zelfs wel iets als: zo sterk dat conflicterende materiaalgebruik.

Waarom is iets mooi? En waarom is iets goed? Tja, ik heb vele, véle gortdroge essays over oude en nieuwe kunst gelezen en in ieder geval wat mooi betreft besloten: hoe mooier het werk, hoe slechter erover wordt geschreven.

Gelukkig begon X me uit te leggen waarom het werk goed was. En zoals meestal in dat soort gevallen, vertelde hij niet zozeer over wat ik zag, maar vooral over waar het aan refereerde, over de ideeën waar het uit voortkwam: over de hoogstpersoonlijke zoektocht van de kunstenaar.

En even werd ik als de moderne museumbezoeker, een lid van de zwijgende massa die devoot luistert naar de audiotour op de koptelefoon en niet in een museum maar op een Open Universiteit lijkt rond te lopen. Read more

Journal Of Anthropological Films

![]() Film cameras, video and sound recorders have for decades been used by anthropologists as research tools, for collecting data, for documentation, for advocacy, for representing a case or a group of people, for disseminating empirical insights and for communicating research findings. For the first time in the history of Visual Anthropology anthropological film can now be published on par with written articles, assessed by peers, and inscribed in international credential systems of academic publication as the Nordic Anthropological Film Association (NAFA) has launched this first edition of Journal of Anthropological Films (JAF)

Film cameras, video and sound recorders have for decades been used by anthropologists as research tools, for collecting data, for documentation, for advocacy, for representing a case or a group of people, for disseminating empirical insights and for communicating research findings. For the first time in the history of Visual Anthropology anthropological film can now be published on par with written articles, assessed by peers, and inscribed in international credential systems of academic publication as the Nordic Anthropological Film Association (NAFA) has launched this first edition of Journal of Anthropological Films (JAF)

Go to: http://boap.uib.no/index.php/jaf/index

Editorial

The Nordic Anthropological Film Association (NAFA) has launched the Journal of Anthropological Films (JAF)

Film cameras, video and sound recorders have for decades been used by anthropologists as research tools, for collecting data, for documentation, for advocacy, for representing a case or a group of people, for disseminating empirical insights and for communicating research findings. For the first time in the history of Visual Anthropology anthropological film can now be published on par with written articles, assessed by peers, and inscribed in international credential systems of academic publication as the Nordic Anthropological Film Association (NAFA) has launched this first edition of Journal of Anthropological Films (JAF) published by Bergen Open Access Publishing (BOAP).

JAF publishes films that combine documentation with a narrative and aesthetic convention of cinema to communicate an anthropological understanding of a given cultural and social reality. JAF publishes films that stand alone as a complete scientific publication based on research that explore the relationship between “contemporary anthropological understandings of the world, visual and sensory perception, art and aesthetics, and the ways in which aural and visual media may be used to develop and represent those understandings” to borrow words from Paul Henley (in Flores, American Anthropologist, Vol 111, No.1, 2009:95). While most films will stand for themselves, only accompanied by an abstract, supplementary text will be accepted when it adds productively to the anthropological analysis and in case the peer-reviewers will ask for it. Read more

Boxing Humans

Well, moving in the academic realm is too often about boxing humans – yes, both sides going together: putting people into boxes and brutally beating them up. The following a letter I sent to relevant newspapers as comment on what is going on, how students [and lecturers] are mal-treated, disrespectful encounters when students are following their curiosity. It makes me increasingly sad, and I feel deeply ashamed …

Well, moving in the academic realm is too often about boxing humans – yes, both sides going together: putting people into boxes and brutally beating them up. The following a letter I sent to relevant newspapers as comment on what is going on, how students [and lecturers] are mal-treated, disrespectful encounters when students are following their curiosity. It makes me increasingly sad, and I feel deeply ashamed …

Dear colleagues,

adding to the various discussions on ranking and formalistic approaches to studying, admission to universities and performance of third-level teaching and research, one point is easily overlooked – the following example is perhaps extreme, though not necessarily completely exceptional.

I worked for two years as professor of economics at Bangor College China, Changsha [BCC] before taking up my current position as research fellow at the Max-Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy in Munich, Germany. Still, one persisting bond to the previous job is concerned with writing references for some students. Some universities where students applied, accepted only references, requiring my mail-address from the previous job – but shouldn’t universities at this time and age accept that scholars are moving, following ambitions and calls in other positions? This means: they should also accept that mail addresses change, and one may even prefer to use a non-institutional address. Anyway, I mentioned the BCC-mail address – however, sending a mail to that address is answered by an auto-reply referring the sender to another address. This is the first point where the institution that was seeking the reference – the Graduate School, The Chinese University of Hong Kong – failed. They ignored the auto-reply and I did not know about the request they sent. Finally I was made aware of it [by the bright applying student], checked the dormant mail box and continued to the website for the submission of the reference. A form opened [after going through a more or less cumbersome procedure], asking for replies to multiple choice questions. I still think students are not made up of multiple choice elements, instead: they are real beings, humans with a multifaceted personality that cannot be squeezed into such forms – even when considering data-processing as an at-times appropriate tool. So, instead of ticking the boxes I preferred skipping them, attaching a recommendation letter instead. However, the system did not allow me to submit the letter unless I would first answer the multiple-choice questions which would feed into a one-dimensional profile. I complained, sent the letter as a mail attachment – and did not receive a reply by the said office of the Hong Kong University. At some stage, I agreed – honestly disgusted by the lack of qualification and respect towards students – ticked the boxes and attached the letter [again cumbersome, as one had to enter a code which was not clearly legible, not allowing to distinguish 0 and O]. I sent another letter of complaint to the Graduate School, The Chinese University of Hong Kong – which was again answered to the BCC address, and again they failed to resend the mail to the e-mail address mentioned in the auto-reply.

If these are the standards of entering higher education, one should not be surprised that at the other end, i.e. at the time of finishing studies, many people have difficulties. They feel their creativity being limited by the requirements of publishing, acquiring funding and the competition along lines of subordination under expectations instead of striving for innovation [see Maximilain Sippenauer: Doktor Bologna; Sueddeutsche Zeitung, 20.10.2017: 11]

Still, it is a bit surprising that all this is well known and still not much is changing. Surprising … ? Perhaps it is not really surprising if we consider that the income of top-administration posts increase while the income of lecturers does not follow accordingly [see for instance the article titled: Times Higher Education pay survey 2016 in The Times Higher Education;https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/times-higher-education-pay-survey-2016%5D.

It seems that there is a long way towards ‘supporting the brightest by open systems’, overcoming the dominantadministrative policy of ‘wedge the narrowest by furthering their smart submission’.

Sincerely

Peter Herrmann