Graham Greene And Mexico ~ A Hint Of An Explanation

In a short letter to the press, in which he referred to Mexico, Graham Greene substantially expressed his view of the world.

“I must thank Mr. Richard West for his understanding notice of The Quiet American. No critic before, that I can remember, has thus pinpointed my abhorrence of the American liberal conscience whose results I have seen at work in Mexico, Vietnam, Haiti and Chile.”

(Yours, etc., Letters to the Press. 1979)

Mexico is a peripheral country with a difficult history, and undeniably the very long border that it shares with the most powerful nation on earth has largely determined its fate.

After his trip to Mexico in 1938, Greene had very hard words to say about the latter country, but then he spoke with equal harshness about the “hell” he had left behind in his English birthplace, Berkhamsted. He “loathed” Mexico…” but there were times when it seemed as if there were worse places. Mexico “was idolatry and oppression, starvation and casual violence, but you lived under the shadow of religion – of God or the Devil.”

However, the United States was worse:

“It wasn’t evil, it wasn’t anything at all, it was just the drugstore and the Coca Cola, the hamburger, the sinless empty graceless chromium world.”

(Lawless Roads)

He also expressed abhorrence for what he saw on the German ship that took him back to Europe:

“Spanish violence, German Stupidity, Anglo-Saxon absurdity…the whole world is exhibited in a kind of crazy montage.”

(Ibidem)

As war approached, he wrote: “Violence came nearer – Mexico is a state of mind.” In “the grit of the London afternoon”, he said, “I wondered why I had disliked Mexico so much.” Indeed, upon asking himself why Mexico had seemed so bad and London so good, he responded: “I couldn’t remember”.

And we ourselves can repeat the same unanswered question. Why such virulent hatred of Mexico? We know that his money was devalued there, that he caught dysentery there, that the fallout from the libel suit that he had lost awaited him upon his return to England, and that he lost his reading glasses, among other things that could so exasperate a man that he would express his discontent in his writing, but I recall that it was one of Greene’s friends, dear Judith Adamson, who described one of his experiences in Mexico as unfair. Why?

The answer might lie in the fact that he never mentioned all the purposes of his trip.

The answer might lie in the fact that he never mentioned all the purposes of his trip.

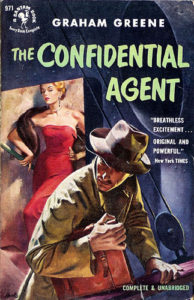

In The Confidential Agent, one of the three books that Greene wrote after returning to England, working on it at the same time as The Power and the Glory, he makes no mention whatsoever of Mexico, but it is hard to believe that the said work had nothing to do with such an important experience as his trip there.

D, the main character in The Confidential Agent, goes to England in pursuit of an important coal contract that will enable the government he represents to fight the fascist rebels in the Spanish Civil War, though Greene never explicitly states that the country in question is Spain. The said confidential agent knows that his bosses don’t trust him and have good reason not to do so, just as he has good reason to mistrust them.

We, who know Greene only to the extent that he wanted us to know him, are aware that writers recount their own lives as if they were those of other people, and describe the lives of others as if they were their own. Might he not, then, have transferred to a character called D, in a completely different setting, his own real experiences as a confidential agent in Mexico?

Besides wishing to witness the religious persecution in Mexico first-hand, his mission might also have been to report on developments in the aforesaid country and regarding its resources -above all its petroleum- in view of the imminent outbreak of the Second World War. Read more

David Van Reybrouck ~ Zink (2016) met Mohamed El Bachiri en Een jihad van liefde (2017)

David Van Reybrouck tekent in ‘Zink’ het verhaal op van Joseph Rixen, zoon van Maria Rixen, dienstmeisje bij een fabriekseigenaar in Düsseldorf. Nadat ze van hem zwanger was geraakt en verstoten, kwam ze in het najaar 1902 terecht in Neutral Moresnet, “waar meer meisjes naar toe trokken en waar men je met rust liet”. Haar zoon groeit op in een pleeggezin, waar zijn naam van Joseph in Emil Pauly veranderd. Hij wordt speelbal van de ontwrichtende (oorlogs)geschiedenis van dit ministaatje, dat van 1816 tot 1919 het buurland was van Nederland, België en Duitsland. Gedurende een ruime eeuw bezat het een eigen vlag, een eigen bestuur, een eigen rijkswacht en een eigen nationaal volkslied in het Esperando. Ooit

moest het de eerste staat worden waar de officiële taal Esperanto was. Men vond er o.a. zink.

De jonge Emil, verwekt in Pruisen, geboren in neutraal gebied, woont sinds 1915, zonder te verhuizen, voor de volgende drie jaar in het westelijk deel van het Duitse keizerrijk. Na de wapenstilstand in 2018 wordt Brussel zijn hoofdstad; hij is pas vijftien en al aan zijn derde nationaliteit toe. Na zijn dienstplicht in het Belgische leger, trouwt Emil met Jeanne Lafèbre,

afkomstig uit Tilburg. Tussen 1934 en 1950 worden elf kinderen geboren, negen zonen en twee dochters. Ze wonen in Kelmis, waar hij bakker is.

In mei 1940 valt Hitler België binnen en annexeert het voormalige Neutraal Moresnet. Inwoners krijgen de Duitse nationaliteit en moeten onder de Wehrmacht gaan dienen. Het nazi bestuur wil Jeanne eren met het ‘Ehrenkreuz der Deutsche Mutter’, hetgeen ze weigert.

“Wat heeft zij als Nederlandse die naar België is verhuisd te maken met een Führer die beweert dat het gezin ‘het slagveld van de moeder’ is?” Als het zevende kind is geboren, eist de overheid dat hij als Duits staatsburger de voornaam en het peterschap van Hermann Wilhelm Göring krijgt. Voor de administratie wordt deze zoon Leo gedoopt, voor de kerk naar de Belgische vorst Leopold, de ouders wilden niet al te provocerend zijn. In 1943, na de nederlaag bij Stalingrad, wordt Emil Rixen ingelijfd bij de Wehrmacht; later deserteert hij. Na de bevrijding keert hij terug bij zijn gezin, maar wordt gearresteerd door

een ondergrondse verzetsorganisatie. Niet als Belg, verdacht van collaboratie, maar als Duitser in dienst van de Wehrmacht. Read more

May Day 2018: A Rising Tide Of Worker Militancy And Creative Uses Of Marx

International Workers’ Day grew out of 19th century working-class struggles in the United States for better working conditions and the establishment of an eight-hour workday. May 1 was chosen by the international labor movement as the day to commemorate the Haymarket massacre in May 1886. Ever since, May 1 has been a day of working-class marches and demonstrations throughout the world, although state apparatuses in the United States do their best to erase the day from public awareness.

In the interview below, one of the world’s leading radical economists, Jawaharlal Nehru University Professor Jayati Ghosh, who is also an activist closely involved with a range of progressive and radical social movements, discusses the significance of May Day with C.J. Polychroniou for Truthout. She also analyzes how different and challenging the contemporary economic and political landscape has become in the age of global neoliberalism, examining the new forms of class struggle that have surfaced in recent years and what may be needed for the re-emergence of a new international working-class movement.

C.J. Polychroniou: Jayati, each year, people all over the world march to commemorate International Worker’s Day, or May 1. In your view, how does the economic and political landscape on May Day, 2018, compare to those on past May Days?

Jayati Ghosh: Ever since the eruption of workers’ struggles on May 1, 1886, commemorating May Day each year reminds us of what organized workers’ movements can achieve. Over more than a century, these struggles progressively won better conditions for labor in many countries. But such victories — and even such struggles — have now become much harder than they were. Globalization of trade, capital mobility and financial deregulation have weakened dramatically the bargaining power of labor vis-à-vis capital. Perversely, this very success of global capitalism has weakened its ability to provide more rapid or widespread income expansion. As capitalism breeds and results in greater inequality, it loses sources of demand to provide stimulus for accumulation, and it also generates greater public resentment against the system.

The trouble is that, instead of workers everywhere uniting against the common enemy/oppressor, they are turned against one another. Workers are told that mobilizing and organizing for better conditions will simply reduce jobs because capital will move elsewhere; local residents are led to resent migrants; people are persuaded that their problems are not the result of the unjust system but are because of the “other” — defined by nationality, race, gender, religion, ethnic or linguistic identity. So this is a particularly challenging time for workers everywhere in the world. Confronting this challenge requires more than marches to commemorate May Day; it requires a complete reimagining of the idea of workers unity and reinvention of forms of struggle. Read more

- Page 2 of 2

- previous page

- 1

- 2