Rebecca Dalzell ~ A City To Grow Into

“It sounds utopian, I know,” says Daniel Haime, standing over the map of Serena del Mar, the city he is building on the Caribbean Sea. He plans to transform a 2,500-acre site outside Cartagena, Colombia – which his family bought in 1968 – into a lively metropolis. There will be a world-class hospital, low-income housing and state-run schools, a marina and bike trails, a luxury hotel and waterfront dining. One day, vaporetti on the lagoon could connect Serena del Mar to downtown Cartagena.

It seems like an auspicious time to build a new city in Colombia. In 2016, the government and theFARC rebel group signed a peace deal ending 50 years of conflict. A cautious optimism buoys the economy. Bogotá and Medellín, the country’s largest cities, have become models for smart urban design. But not Cartagena. It may be one of the fastest-growing cities in Colombia but, according to Nicolás Galarza Sanchez, a research scholar at New York University’s Marron Institute of Urban Management, it is also a case study in how not to expand. It has spread in a fashion typical of South America: high-rise condominiums for the rich have sprouted along the waterfront while poor settlements made up of squalid, informal dwellings have grown in areas prone to flooding. Galarza and his colleagues are working with the Colombian government to help manage growth in 100 cities across the country.

Read more: https://www.1843magazine.com/a-city-to-grow-into

Amílcar Sanatan ~ The Little-Known Stories Of two Revolutionary Caribbean Women

There is a ‘lost history’ of radical women and women’s organizing in the Caribbean for social and economic justice that changed our landscape for more than a century.

When we think of great leaders, we think of presidents, prime ministers and heads of revolutionary movements. In our collective memory, we sometimes forget the immense sacrifices of left organizers for social, economic and political change. Yet, not all revolutionaries and martyrs are equal.

Working class, non-white, activist, and left women from the Global South suffer from the greatest invisibility. There is a ‘lost history’ of radical women and women’s organizing in the Caribbean for social and economic justice that changed our landscape for more than a century.

In what will forever be remembered as the July 26 Movement, a young Fidel Castro led a failed attack against the Moncada army barracks in Santiago de Cuba in an attempt to inspire a national uprising against dictator Batista. While many of his comrades were slaughtered in the action, the passionate and idealistic Fidel, in 1954 wrote a lengthy critique of capitalism in the Isle of Pines prison, decrying the social and economic ills of Cuba under dictatorial rule instead of making a defense regarding the charges brought against him.

In a speech that has been remembered for one of its precious lines, “History will absolve me,” Fidel Castro joined the distinguished tradition of revolutionaries who defended themselves in court by advancing their radical political beliefs. One year before Fidel would be absolved by history, Claudia Jones, made her defense in a U.S. court challenging the imprisonment she faced because of her communist beliefs.

Read more: http://caricomreparations.org/little-known-stories-two-revolutionary-caribbean-women/

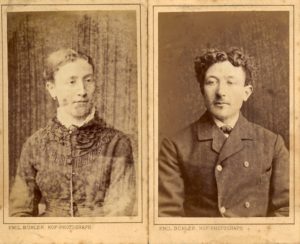

Uit het fotoalbum

Het echtpaar Bermann had vijf kinderen:

Isidor Bermann – 1883 (Konken) – 1935 (Ludwigshafen)

Mathilde Bermann -1884 (Konken) – 1942 (Auschwitz)

Ernst Bermann – 1888 (Konken) – 1943 (Sobibor)

Luitpold Bermann – 1891 (Konken) – ? (U.S.A.)

Paulina Bermann – 1895 (Konken) – 1945 (Bergen Belsen)

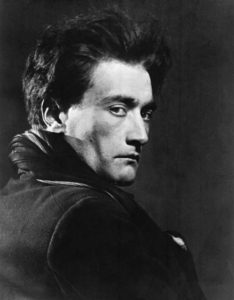

Islamic State & The Artaudian Theatre Of Cruelty

Abstract

Intrigued by the idea that the Islamic State’s media is performing Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, we questioned in this article whether Islamic State’s use of media does indeed compare to the hellish visions of the notorious French dramaturge, and consequently ask ourselves, if so, how we should interpret and give meaning to the eventual connection between two subjects that seem so far apart, and yet so close to each other: the Theatre of Cruelty and the gruesome religiously inspired videos of Islamic State.[i] The results of our analysis confirm significant parallels between the Theatre of Cruelty and the cruel videos of Islamic State. Considering the fact that the message of cruelty is central to many of their videos, we conclude that ‘Islamic State’s media productions indeed implement the characteristics underlying Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.’ But what does all this mean? Cruelty and violence are indeed elements of human being’s nature. Humankind has to embody it in one way or the other, and from that perspective, it is much better to incorporate these darker sides of men in the metaphysical sphere. We are deliberately speaking here of humankind, irrespective of religious or ethnic background, because there are Westerners and Easterners that have learnt this dear lesson: acknowledging the dark side of men and expressing it in art.

Key words: # Islamic State # Artaud # Theatre # Propaganda # Cruelty # Hermeneutics # Interpretation

1 Introduction

‘Artaud, a sickly child twisted further by the shock of World War I, wanted his actors to “assault the senses” of the audience, shocking parts of the psyche that other theatrical methods had failed to reach. Well, IS has read the book. It’s been obvious since September 11 that we’re living in an age of vicious political theatre. That’s what ‘terrorism’ is: the manipulation of large populations by shock and awe and ‘liberating unconscious emotions’’ (to quote Artaud).’[ii]

‘If the attacks on the Twin Towers used the iconography of the Hollywood action blockbuster, the beheadings in the desert evoke drama far more ancient – Old Testament strife, Hellenic legend. [..]It may sound unlikely, but ISIS is carrying out in extremis the program of the ‘Theatre of cruelty’ of the influential French dramaturgedemiurge Antonin Artaud.’[iii]

In the summer of 2014, the geopolitical stage was shaken by the Islamic State videos. Starting off a series of terrifying communiqués with a video of the beheading of journalist James Foley in A message to America, Islamic State quickly set a new standard for extremists’ use of media as a propaganda tool. Now that the extreme display of violence has become the hallmark of Islamic State terror, certain journalists have suggested a link between these brutal videos and dramatist Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) and his ‘Theatre of Cruelty’. We were intrigued by the idea that the correspondence between Islamic State’s media outlets and Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty might actually go beyond the shared predominance of cruelty and have taken the suggestion made by Sakurai as a cue to research whether Islamic State’s use of media does indeed compare to Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty on a more fundamental level. And consequently ask ourselves how, if so, we should interpret and give meaning to the eventual connection between two subjects that seem so far apart, and yet so close to each other: the Theatre of Cruelty and the gruesome religiously inspired videos of Islamic State.

The research done is comparative in nature. By comparing and contrasting the principal underlying ideas, the audience/performance relation, and the performance itself of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and Islamic State’s video productions, we hope to arrive at a detailed and nuanced understanding if and if yes, how Islamic State and Artaudian theatre relate to each other. The possible connection between both being eventually confirmed, we will consequently dwell on the meaning of such connection. Read more

Mati Shemoelof ~ …reisst die Mauern ein zwischen ‘uns’ und ‘ihnen’

Onlangs verscheen van dichter, auteur, uitgever, en bekende stem in de Arabisch-joodse Mizrahi-Beweging Mati Shemoelof …reisst die Mauern ein zwischen ‘uns’ und ‘ihnen’. Tekst en gedichten wisselen elkaar af.

Het heeft Mati Shemolof enige tijd gekost om te begrijpen dat de geschiedenis van zijn familie uit de geschiedenisboeken is verwijderd en in de Israëlische samenleving is gemarginaliseerd. Je komt in een soort van diaspora terecht als je van Arabische afkomst bent, terwijl Israël een thuis zou moeten zijn voor joden die naar een joodse staat emigreerden, aldus Shemoelof. Hij nam in 2007 dan ook het initiatief om Echoing Identies: Young Mizrahi Anthology uit te geven met teksten van de derde generatie Mizrachi. Door al zijn ervaringen is Mati Shemoelof zich bewust geworden van de diaspora van anderen, of het nu Syriërs zijn in Berlijn, Afghanen, Libiërs of Oost-Europeanen; maar vooral de diaspora van de Palestijnen uit de periode 1948 en 1967 raakt hem.

Shemoelof’s Perzische grootvader werd in het begin van de 20e eeuw gedwongen uit Mashhad (Iran) naar Haifa te emigreren, dat toen nog bij Palestina hoorde. Haifa van voor 1948 was een moderne stad, waar verschillende culturen vreedzaam naast elkaar leefden, waar zijn opa goed zaken kon doen en vrij was. Maar deze Palestijnse geschiedenis van Haifa is niet meer bekend.

De geschiedenis van zijn moeder is kenmerkend voor een familie van Mizrachim, voor joden met een Arabische cultuur en taal. Ze waren goed geïntegreerd in Irak en over het algemeen seculier. Zij werden echter in 1951 gedwongen van Bagdad naar Israël te emigreren, net als zo’n 120.000 andere Iraakse-joodse burgers, met achterlating van al hun bezit. Dat was onderdeel van de deal tussen Irak en Israël: de zionistische beweging kreeg arbeidskrachten en Irak bezit. Maar eerder had al de Farhud in Irak plaatsgevonden: op 1 en 2 juni 1941 vond een Pogrom plaats tegen joden in Bagdad, waarbij tussen de 150 en 200 doden vielen en van velen hun bezit werd afgenomen.

Nu zijn in Israël muren rondom Palestijnen, maar ook om de Arabische joden is een muur geplaatst. En toch zijn vele Mizrachi, die in armoede leven, niet solidair met de Palestijnen.

Om je te verhouden tot al die muren in Israël, in – en extern, is moeilijk en maakte Mati Shemoelof tot activist van de Mizrachi-Beweging, die strijdt voor sociale rechtvaardigheid en erkenning van identiteit. De Mizrachi-Beweging onderzoekt met name de verwantschap tussen hun identiteit en die van de Palestijnen en de Arabische wereld. Read more

Human Rights, State Sovereignty, And International Law

We live in an era where virtually every government on the planet claims to pay allegiance to human rights and respect for international law. Yet, violations of human rights and plain human decency continue to occur with disturbing frequency in many parts of the world, including many allegedly “democratic” countries such as the United States, Russia, and Israel. Indeed, Donald Trump’s immigration policy, Putin’s systematic repression of dissidents, and Israel’s abominable treatment of Palestinians seem to make a mockery of the principle of human rights. Is this because “faulty” forms of government or because of some Inherent tension between state sovereignty and human rights? And what about the international regime of human rights? How effective is it in protecting human rights? Richard Falk, a world renowned scholar of International Relations and International Law sheds light into these questions in the exclusive interview below with C. J. Polychroniou.

Richard Falk is Alfred G. Milbank Emeritus Professor of International Law, Politics, and International Affairs at Princeton University and the author of some 40 books and hundreds of academic articles and essays. Among his most recent books are A New Geopolitics (to be published in December 2018); Palestines’s Horizon: Toward a Just Peace (2017); Humanitarian Intervention and Legitimacy Wars: Seeking Justice in the 21st Century (2015); Chaos and Counterrevolution: After the Arab Spring (2014); and Path to Zero: Dialogues on Nuclear Dangers (2012).

C. J. Polychroniou: Richard, you taught International Law and International Affairs at Princeton University for nearly half a century. How has international law changed from the time you started out as a young scholar to the present?

Richard Falk: You pose an interesting question that I have not previously thought about, yet just asking it makes me realize that this was a serious oversight on my part. When I started thinking on my own about the role and relevance of international law during my early teaching experience in the mid-1950s, I was naively optimistic about the future, and without being very self-aware, I now understand that I assumed that moral trajectory that made the future work out to be an improvement on the past and present, that there was moral progress in collective behavior, including at the level of relations among sovereign states. I thought of the expanding role of international law as a major instrument for advancing progress toward a peaceful and equitable world, and endeavored in my writing to encourage the U.S. Government to align its foreign policy with international law, arguing, I suppose in a liberal vein, that such alignment would promote a better future for all while at the same time being beneficial of the United States, especially given the overriding interest in avoiding World War III.

My views gradually evolved in more critical and nuanced directions. As my interests turned toward the dynamics of decolonization, I came to appreciate that international law had legitimized European colonialism, and the exploitative arrangements that were imposed on the countries of the global south. I realized that the idealistic identification of international law with peace and justice was misleading, and at best only half of the story. International law was generated by the powerful to serve their interests, and was respected only so long as vital interests of these dominant states were not threatened.

The Vietnam War further influenced me to adopt a more cautious view of international law, and even more so, of the United Nations. I opposed the war from the outset from the perspective of international law, citing the most basic prohibitions on intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign states and the core prohibition of the UIN Charter against all recourses to aggressive force. I did find it useful to put the debate on Vietnam policy in a legal format as the country was then under the sway of liberal leadership, although tinged with Cold War geopolitics and ideology. The defenders of Vietnam policy, motivated by Cold War considerations, relied on legal apologetics as well as claims that it was important for world order to contain the expansion of Communist influence, and that the adversary in Vietnam was China rather than North Vietnam. The legal debate to which I devoted energy for ten years convinced me that international law on war/peace issues was subordinated to geopolitics including by the Western democracies, and that even so, legal counter-arguments were always available to governments eager to disguise their reliance on geopolitical priorities. International law remains useful and even necessary for the routine transnational activities of people and governments, stabilizing trade and investment relations, but often in ways that favor the rich, and issues pertaining to questions of safety, communications, and tourism exhibit a consistent adherence to an international law framework. Read more