The Growing Wealth Gap Marks The Return Of Oligarchy

One of the most striking features of our era is the widening gap between rich and poor. In fact, wealth inequality may be higher today than any other era, although we lack the data to draw meaningful comparisons with the distant past. Moreover, the gap between the haves and the have-nots seems to be growing, as the annual reports from the development charity Oxfam clearly indicate. What are the key reasons for the growing divide between rich and poor, especially when governments claim that there is a recovery underway since the 2008 global financial crisis? And what can be done to reorganize society so wealth is no longer concentrated into so few hands while millions of people live in extreme poverty or are barely subsisting? In the interview below, Thomas Weisskopf, emeritus professor of economics at the University of Michigan and a long-time member of the Democratic Socialists of America, offers his insights on the state of economic injustice.

C.J. Polychroniou: Professor Weisskopf, according to the 2019 Oxfam report, a handful of billionaires own as much wealth as the poorest half of the world’s population. In fact, 2018 was a year in which the rich got richer again and the poor, poorer. Do we know the primary culprits behind the ever-growing gap in economic well-being between rich and poor?

Thomas Weisskopf: There are both economic and political reasons for the growing wealth gap between the very rich and the poor. The natural tendency of capitalism is to generate both overall economic growth and ever-increasing inequality in both wealth and income. Most people do not have the opportunity to acquire much wealth, but those who have inherited or accumulated a certain amount of wealth have many opportunities to increase it, and the more wealth you have, the easier it is to do so. Wealth is everywhere much more unequally distributed than income, because those who have wealth can use it to generate even more. The distribution of wealth has a huge impact on the distribution of income, because wealth is an important source of income — especially for the very rich. The underlying unequalizing tendency of capitalism can be interrupted by catastrophic developments — such as wars or major economic crises, which can shrink the wealth of an entire capitalist class, or natural disasters which can destroy the wealth of individuals whose wealth is vulnerable to such events. World Wars I and II, as well as the Great Depression of the 1930s, had the effect of reducing the degree of wealth and income inequality around the world. The natural unequalizing tendency of capitalism can also be limited, and sometimes even reversed, by political intervention. From the end of World War II to the 1970s the capitalist world achieved rapid economic growth without much increase in wealth and income inequality, because most governments took responsibility for assuring that the gains from growth would be widely shared. They did this through a variety of means, including relatively high (by current standards) taxes on wealth and income, which funded government spending on public programs that had the effect of redistributing income and opportunities from richer to poorer segments of the populations, well as policies that curbed the power of large corporations and protected workers from exploitation by employers. Beginning in the late 1970s, government policies in many capitalist countries — most markedly in the U.K. and the U.S. — shifted toward less redistributive tax and spending policies, less regulation of large corporations, and less protection for workers. Read more

Herdenking Februaristaking 2019 – Toespraak Burgemeester Halsema

25 februari 2019. In de toespraak bij de herdenking van de Februaristaking verwijst burgemeester Femke Halsema naar het dagboek van Paula Bermann.

Zie: https://www.amsterdam.nl/burgemeester/toespraak

Paul Scheffer ~ De vorm van vrijheid

Paul Scheffer (1954), publicist en hoogleraar Europese studies, schreef voor de Maand van de Filosofie 2016 het essay De vrijheid van de grens. In ‘De vorm van vrijheid ‘verdiept hij zijn inzichten omtrent grenzen verder, mede naar aanleiding van de vluchtelingencrisis, de Brexit, en de muur die Trump wil bouwen. Vrijheid zonder vorm is niet mogelijk: een open samenleving vraagt om grenzen, aldus Scheffer.

Paul Scheffer begint zijn boek met een filosofische beschouwing over de betekenis van het kosmopolitisme. Het kosmopolitisme is een principieel pleidooi om door het overbruggen van verschillen duurzame vrede voort te brengen, een belangrijke en ook omstreden traditie in het Europese denken. De filosofen Plato en Aristoteles waren de eersten die dachten over wereldburgerschap. De Renaissance plaatste later het ideaal van kosmopolitisme weer op de agenda. Scheffer gaat in op de filosofen Kant en Erasmus om te illustreren dat men al lang op zoek was naar een gelijkheidsideaal voorbij de grenzen, maar dat zij toch ook gevangen waren in vooropgezette ideeën met een religieuze of nationale strekking. Het kosmopolitisme en pacifisme van Erasmus hebben vanwege de beperkingen en ook tegenstrijdigheden van dat ideaal nu nog steeds betekenis. De vragen die Erasmus opwerpt als ‘Hoe verhouden macht en moraal zich in Europa’ en ‘Baseren we ons op een seculier uitgangspunt dat verder strekt dan een veronderstelde joods-christelijke erfenis?’ zijn nog steeds actueel.

Kant, met zijn filosofie van ‘de eeuwige vrede’ omarmt het wereldburgerschap, een scheiding der machten, gelijkheid voor de wet en het idee van vertegenwoordiging. Het primaat ligt bij de binnenlandse staatsordening in de internationale politiek, het volkenrecht behoort te zijn gebaseerd op een federalisme van vrije staten en het wereldburgerrecht behoort beperkt te zijn tot de voorwaarden van algemene gastvrijheid. Read more

Le nihilisme: 1. Le nihilisme dans la pensée grecque antique

1. Y-a-t-il ou non un nihilisme en Grèce Ancienne ?

Les philosophes Barbara Cassin et Francis Wolff évoquent les origines du nihilisme. Commentant à tour de rôle les définitions possibles de la doctrine, ils s’attachent à en trouver trace dans la pensée grecque, notamment chez Socrate et le sophiste Gorgias.

2: Le père Stanislas Breton, philosophe et auteur de ‘La pensée du rien’ (Pharos), distingue la pensée du rien “par excès”, tel le bouddhisme, du rien “par défaut”, qui recouvre la doctrine nihiliste proprement dite. Puis il définit les principaux mouvements philosophiques liés à la pensée du néant par défaut, l’approche de Nietzsche, et les différentes catégories du nihilisme qu’il a dégagées : nihilisme optatif, optionnel absolu, de conséquence.

3: Christine Goémé reçoit le philosophe Gérard Lebrun à propos de Schopenhauer, initiateur malgré lui du nihilisme ; il évoque l’écrivain russe Tourgueniev, l’un des inventeurs du terme “nihilisme”, l’ouvrage de Schopenhauer ‘Le Monde comme volonté et comme représentation’ et l’influence de Schopenhauer en France et à l’étranger.

4. Christine Goémé reçoit Georges Leyenberger et Jean Jacques Forte, organisateurs d’un colloque sur le nihilisme qui s’est tenu à Strasbourg, suivi d’une publication. Ils parlent des différentes manières de comprendre le nihilisme, et donc le “rien” et le “vide”, en faisant référence notamment à Nietzsche et à Kant.

5. Entretien avec Alain Badiou à propos du nihilisme. Il donne sa définition du nihilisme, dont le point ultime serait le terrorisme (nihilisme actif). Propos sur le nihilisme de Friedrich Nietzsche. Il existe aussi un nihilisme passif, qu’il qualifie d'”inauthentique”, il s’agit surtout de “gloseries”. La personnalité de Sofia Kovalevskaia, nihiliste russe et mathématicienne. La grandeur de son oeuvre. Ce que veut dire être nihiliste aujourd’hui dans une société menée par l’argent. Le nihilisme se traduit par une révolte émeutière aveugle face au néant monétaire. Ce nihilisme est en défaut d’acte et dénué de pensée. Il faudrait une vraie critique radicale du nihilisme du monde. Les relation entre l’art contemporain et le nihilisme. L’élément nostalgique du nihilisme et la notion “d’éternel retour” chez Nietzsche.

A World Political Party: The Time Has Come

Shared problems require shared action. The world economy and deepening global risks bind us together, but we lack the collective global agency required to address them. A sustainable global future will be impossible without a fundamental shift from the dominant national mythos to a global worldview, and the concomitant creation of institutions with transformative political agency. A world political party would be well-suited to bring about such a shift. Although such a party will not materialize overnight, it can emerge from the chrysalis of activism and experimentation already forming on the world stage.

The transnational Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (DiEM25) is a compelling experiment in this vein, providing useful lessons for a world political party proper. Although the challenges to forming a transformative world party are profound, the risks of inaction are grave – and the rewards of success momentous.

Party Time

We now understand how small our planet has become. The local and global have become profoundly intertwined as our daily activities depend on the workings of the world economy. Common risks, like ecological crises and weapons of mass destruction, tie all our fates together.

Despite such interconnectedness, people’s everyday experiences still differ greatly. For example, consider the contrasts between a day in the life of a high school teacher in Finland, a textile worker in China, a CEO of a multinational corporation in Brazil, and a janitor in Kenya—a case study in lateral and vertical diversity. Their lives’ possibilities are interwoven and shaped by the global economy, but in sharply divergent ways. Shared problems require shared action. But to achieve collective agency on the global level, disparate individuals must learn to see themselves (and their daily lives) as fundamentally connected to one another through common global structures, processes, and challenges. Such collective learning has the potential to politicize the world economy and the institutions that govern it. Rather than being treated as immutable, these institutions can and must become the subject of political contestation. Both radically reforming existing institutions and building new ones must be on the agenda. Seeing the world system as malleable goes hand in hand with the quest for globalized political agency, for advancing transformative visions of “another world.”

The roots of the contemporary quest go back to the formation of transnational political associations in the nineteenth century with the burgeoning peace and labor movements. A century later, in the 1960s and 1970s, new movements for gender and racial equality, nuclear disarmament, and environmental justice sparked global organizing and activism. In the 1980s, economic globalization became an era-defining issue. Then, as the walls of the Cold War came tumbling down and the Internet eroded barriers to communication, the concept of global civil society took hold. To this day, civil society carries the banner of transformative hope, expressed through pursuit of peace, justice, democracy, economic well-being, and ecological sustainability.

The growing organization and influence of global civil society can be seen in the human rights movement. For example, an international criminal court was

first proposed in 1872 in response to the atrocities of the Franco-Prussian War. However, the NGO Coalition for an International Criminal Court (ICC), which featured prominent human rights organizations, was not founded until 1995. By the time the Rome Statute was adopted in July 1998, more than 800 organizations had joined the campaign; in the early 2000s, the number was more than one thousand. The ultimate creation of the ICC, though noteworthy, was an achievement tempered by the nonparticipation of China, Russia, and the US, among others, and by accusations, especially by African states, that the court has been guilty of applying double standards. Read more

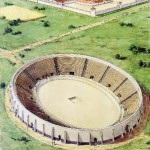

De grond lezen als een boek ~ Graven naar de geschiedenis van de Cariben. Met Corinne Hofman

Toen Columbus meer dan 500 jaar geleden de oceaan over zeilde op zoek naar de Nieuwe Wereld, stapte hij het eerst aan wal in het Caribisch gebied. Hoe leefde de Indiaanse bevolking daar? Hoeveel contact was er tussen de eilanden? En hoe verliep de ontmoeting tussen de oude en de nieuwe wereld? Al meer dan 20 jaar zoekt archeoloog Corinne Hofman het antwoord op deze vragen in de Caribische aarde.

Merianprijs

De KNAW Merianprijs is ingesteld om de zichtbaarheid van vrouwelijke wetenschapsbeoefenaren in Nederland te bevorderen en de deelname van vrouwen in de wetenschap in Nederland te stimuleren. De prijs wordt mogelijk gemaakt door SNS REAAL Fonds.

Geproduceerd door Fast Facts

Mogelijk gemaakt door de Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen en het SNS REAAL Fonds

Met dank aan Marja van der Putten, Ilone de Vries, Jimmy Mans, leden Caribische onderzoeksgroep Universiteit Leiden

Met beeld van Johan Gielen, Ben Hull

Gemaakt door: Aline Idzerda 2013

In samenwerking met

Camera & montage: Persistent Vision

Muziek: Daan van West

Grafisch ontwerp: SproetS