Capitalist Workplaces Set Bosses Up To Be Authoritarian Tyrants

Long before the growing interest in economic inequality facing contemporary capitalist societies, radical thinkers and union organizers were concerned about the authoritarian governance in workplaces. Unfortunately, this concern seems to have taken a back seat in political philosophy during the present era. Elizabeth S. Anderson, a professor of philosophy and women’s studies at the University of Michigan, is seeking to remedy this with her trenchant analyses of the coercive and hierarchical nature of capitalist firms and corporations. Her book Private Government offers an important reminder that bosses tend to be dictators and that workers’ lives are essentially at the mercy of private government.

C.J. Polychroniou: In your book Private Government, you analyze the different facets of modern workplaces and argue that firms and corporations operating under so-called “free market” norms and arrangements are actually coercive and hierarchical in nature, and rule over workers’ lives as authoritarian governments tend to do. Can you elaborate a bit on these highly challenging ideas, as most people don’t seem to view workplaces as dictatorships?

Elizabeth S. Anderson: Look at the organizational chart of any firm: You will see a hierarchy of offices, with subordinates reporting to their bosses, and bosses issuing orders to subordinates that must be obeyed on pain of sanctions such as getting fired, demoted, harassed or denied decent hours. That’s all it takes to make a little government — the power to issue orders to others, backed by threats of punishment. If the workplace is a government, we can ask, what is the constitution of that government? The answer, in nearly all cases where workers lack union representation, is that the constitution of workplace government is a dictatorship. Workers don’t get to elect their bosses. They don’t have a right to participate in the firm’s decision-making about the terms and conditions of their work. For the most part, they have little effective recourse if their bosses abuse them, other than to quit.

Workers even lack the power to hold their bosses to account for a wide range of abuses at work — even when those abuses are illegal, such as sexual harassment and wage theft. The scale of wage theft — effected by forcing workers to work off the clock, work overtime without extra pay and numerous other scams — is vast. It exceeds the sum total of all other thefts in the U.S. The vast majority of workers who are sexually harassed face illegal retaliation at work for complaining. So most keep silent. More and more, employees are forced to sign mandatory arbitration agreements, which strip them of their right to have their case be heard by a neutral judge following legal procedures. Instead, they must go to an arbitrator chosen by their employer, who is bound by no procedures, and knows that the arbitration contract will not be renewed if they render too many judgments in favor of the worker. No wonder workers under mandatory arbitration are far less likely to win their cases, and when they win, receive far less compensation than workers who sue their employer in court. It’s a recipe for mass abuse. While many workers — particularly those in management or with rare skills — get decent treatment, millions of ordinary workers suffer under awful working conditions, low pay, unstable hours, and subjection to discrimination, wage theft and other illegal treatment.

Dictatorial employer control over workers doesn’t even end when workers are off-duty. The default rule in the U.S. is “employment at will.” This means that, with a few exceptions (mostly having to do with discrimination), employers are legally entitled to fire, demote and harass workers for any reason or no reason at all. This rule opens the door to punishing workers for things they do while off-duty. Many workers have been fired because their boss disapproves of their choice of sexual partner, support for candidates and political causes the boss doesn’t like, unconventional gender presentation, recreational use of marijuana on days off and other personal decisions. When a Coke worker can be fired for drinking Pepsi at lunch, it’s easy to see that the scope of employer control over workers’ lives is nearly unlimited. Read more

Rosa Luxemburg Internet Archive

“Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of ‘justice’ but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when ‘freedom’ becomes a special privilege.” – The Russian Revolution

“Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of ‘justice’ but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when ‘freedom’ becomes a special privilege.” – The Russian Revolution

The Library: https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/index.htm

21 juni 1943

Begin van de zomer! Het zou een stralende zomerdag moeten zijn maar het regent. Gisteren was het warm, een onweer zorgde voor regen. De langste dag. Voor ons blijven het lange dagen.

Begin van de zomer! Het zou een stralende zomerdag moeten zijn maar het regent. Gisteren was het warm, een onweer zorgde voor regen. De langste dag. Voor ons blijven het lange dagen.

De schrik van vorige week zit nog in mijn benen en omdat ik Hans eigenlijk zaterdag verwacht (soms komt hij onaangekondigd), zit ik alweer in angst. Stilletjes, want ik mag de anderen niet aansteken, maar mijn angst om Hans en Inge groeit elke dag, neemt enorme proporties aan. Ik weet dat mijn zenuwen me die streek leveren maar de angst om je kinderen is ook zoiets verschrikkelijks.

Morgen komt misschien Inges vriend (vorige week kwam hij niet) en ik blijf onrustig over hoe het met het kind gaat, of zij zich kan aanpassen, of ze kan blijven.

Van Sigrid Undset heb ik Ida Elisabeth gelezen. Wat schrijft die vrouw mooi, eenvoudig, en juist in de eenvoud van haar stijl ligt haar meesterschap. De moeder in haar laat haar zo prachtig schrijven. Baren is alleen het onbewerkte materiaal leveren, laat ze Ida zeggen, daarom mag een moeder haar kinderen nooit loslaten, totdat ze volwassen zijn. Zo dacht ik ook altijd, ik ging nooit op reis, en ik hoor daarover nog steeds verwijten van mijn man, die me dit nooit heeft vergeven.

Van Pierre Benoit heb ik zijn beroemde boek Atlantis gelezen.

Wat een geluk dat hier een tamelijk goede bibliotheek is. Benoit fantaseert over het door Plato beschreven verloren land Atlantis, midden in de Sahara, met koningin Antinea, die een verzameling Europese minnaars aanlegt en die diverse gestrikten – uit liefde gestorven en door een onbekend procedé gebalsemd – in een zaal van haar paleis bewaart.

De geest van de mens die ons door zo’n boek steeds weer bezielt. Het goddelijke in de mens en in de natuur dat je ertoe dwingt te denken dat er toch iets tussen hemel en aarde bestaat wat wij niet begrijpen. Het is alsof een vroegere geest in het hoofd van de nu levenden is gekomen en deze beelden uit oude, oeroude tijden voor ons doet herleven.

En dan de werkelijkheid. Ik word wakker uit een mooie droom als ik zo’n boek lees en ons zie zitten met z’n drieën, ondergedoken, omdat we weer zoveel eeuwen zijn teruggeworpen.

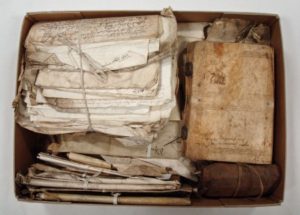

Dutch Prize Papers

HCA 32 / 1845.1: A box with ship’s documents, court papers, ship’s journals, cash books and a wallet with a small French prayer book, seized in the 17th century during the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars. Source: Sailing Letters Journal IV, Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2011, 12; picture: Erik van der Doe

The Prize Papers are documents seized by British navy and privateers from enemy ships in the period 1652-1815. These papers are kept in the archive of the High Court of Admiralty in The National Archives in Kew (London). Approximately a quarter of the Prize Papers originates from Dutch ships. Apart from ship’s journals, lists of cargo, accounts, plantation lists and interrogations of crew members, this collection also contains approximately 38,000 business and private letters. The letters originate from all social strata of society and most of them never reached their intended destination.

Research

The huge variety of the Prize Papers makes it suitable for different types of research. It means that the Prize Papers can be used for a wide range of research topics, for example, for developments in language and dialect, trade, material culture, social relationships and knowledge transfer from the 17th to the 19th centuries. A large international research project by the universities of Oxford and Birmingham led by Jelle van Lottum focused on the migration of sailors and the distribution of human capital, based on records of interrogations of crew members. This research was financed by the Economic and Social Research Council (2011-2016).

The Sailing Letters’ project carried out by the National Library of the Netherlands in 2004, introduced the Prize Papers to a broad group of Dutch researchers. Five Sailing Letters Journals were published between 2008 and 2013 to make this rich and versatile resource even more widely known.

Preservation and digitisation

The award at the end of 2015 of a substantial subsidy to Huygens ING by Metamorfoze, the national programme for the preservation of paper heritage, made it possible to preserve and digitise 144.000 pages of selected documents.

Go to: https://www.huygens.knaw.nl/dutch-prize-papers/

or: https://prizepapers.huygens.knaw.nl/

Sinclair Lewis ~ It Can’t Happen Here

It Can’t Happen Here is the only one of Sinclair Lewis’s later novels to match the power of Main Street, Babbitt, and Arrowsmith. A cautionary tale about the fragility of democracy, it is an alarming, eerily timeless look at how fascism could take hold in America.

Written during the Great Depression, when the country was largely oblivious to Hitler’s aggression, it juxtaposes sharp political satire with the chillingly realistic rise of a president who becomes a dictator to save the nation from welfare cheats, sex, crime, and a liberal press.

Called “a message to thinking Americans” by the Springfield Republican when it was published in 1935, It Can’t Happen Here is a shockingly prescient novel that remains as fresh and contemporary as today’s news.

Chapter I

THE handsome dining room of the Hotel Wessex, with its gilded plaster shields and the mural depicting the Green Mountains, had been reserved for the Ladies’ Night Dinner of the Fort Beulah Rotary Club.

Here in Vermont the affair was not so picturesque as it might have been on the Western prairies. Oh, it had its points: there was a skit in which Medary Cole (grist mill & feed store) and Louis Rotenstern (custom tailoring—pressing & cleaning) announced that they were those historic Vermonters, Brigham Young and Joseph Smith, and with their jokes about imaginary plural wives they got in ever so many funny digs at the ladies present. But the occasion was essentially serious. All of America was serious now, after the seven years of depression since 1929. It was just long enough after the Great War of 1914-18 for the young people who had been born in 1917 to be ready to go to college… or to another war, almost any old war that might be handy.

The features of this night among the Rotarians were nothing funny, at least not obviously funny, for they were the patriotic addresses of Brigadier General Herbert Y. Edgeways, U.S.A. (ret.), who dealt angrily with the topic “Peace through Defense—Millions for Arms but Not One Cent for Tribute,” and of Mrs. Adelaide Tarr Gimmitch— she who was no more renowned for her gallant anti-suffrage campaigning way back in 1919 than she was for having, during the Great War, kept the American soldiers entirely out of French cafés by the clever trick of sending them ten thousand sets of dominoes.

Nor could any social-minded patriot sneeze at her recent somewhat unappreciated effort to maintain the purity of the American Home by barring from the motion-picture industry all persons, actors or directors or cameramen, who had: (a) ever been divorced; (b) been born in any foreign country—except Great Britain, since Mrs. Gimmitch thought very highly of Queen Mary, or (c) declined to take an oath to revere the Flag, the Constitution, the Bible, and all other peculiarly American institutions. Read more

To Be Effective, Socialism Must Adapt To 21st Century Needs

IS socialism making a comeback? If so, what exactly is socialism, why did it lose steam toward the latter part of the 20th century, and how do we distinguish democratic socialism, currently in an upward trend in the U.S., from social democracy, which has all but collapsed? Vijay Prashad, executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and a leading scholar in socialist studies and the politics of the global South, offers answers to these questions.

C.J. Polychroniou: Socialism represented a powerful and viable alternative to capitalism from the mid-1800s all the way up to the third quarter of the 20th century, but entered a period of crisis soon thereafter for reasons that continue to be debated today. In your view, what are some of the main political, economic and ideological factors that help explain socialism’s setback in the contemporary era?

Vijay Prashad: The first thing to acknowledge is that “socialism” is not merely a set of ideas or a policy framework or anything like that. Socialism is a political movement, a general way of referring to a situation where the workers gain the upper hand in the class struggle and put in place institutions, policies and social networks that advantage the workers. When the political movement is weak and the workers are on the weaker side of the class struggle, it is impossible to speak confidently of “socialism.” So, we need to study carefully how and why workers — the immense majority of humanity — began to see the reservoirs of their strength get depleted. To my mind, the core issue here is globalization — a set of structural and subjective developments that weakened worker power. Let’s take the developments in turn.

There were three structural developments that are essential. First, major technological changes in the world of communications, database management and transportation that allowed firms to have a global reach. The global commodity chain of this period enabled firms to disarticulate production — break up factories into their constituent units and place them around the world. Second, the third world debt crisis debilitated the power of national liberation states and states that — even weakly — had tried to create development pathways for their populations in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The debt crisis led to [International Monetary Fund] IMF-driven structural adjustment programs that released hundreds of millions of workers to international capital and for the workforce of the new global commodity chain. Third, the collapse of the USSR and the Eastern bloc, as well as the changes in China provided international capital with hundreds of millions of more workers. What we saw is in this period of globalization was the break-up of the factory form, which weakened trade unions; the impossibility of nationalization of firms, which weakened national liberation states; and the use of the concept of arbitrage to force a race to the bottom for workers. These structural developments, from which workers have not recovered, deeply weakened the workers’ movement. Read more