17 maart 1941

Mijn verjaardag is weer voorbij. En hoe zal het volgend jaar zijn? Wie weet wat er allemaal gaat gebeuren. Het wordt vast en zeker een zwaar, onheilspellend jaar, vol gevaren, angst en dood. Je mag niet nadenken, moet van de ene dag in de andere leven, je geen zorgen maken voor morgen. Maar wie kan dat?

Mijn verjaardag is weer voorbij. En hoe zal het volgend jaar zijn? Wie weet wat er allemaal gaat gebeuren. Het wordt vast en zeker een zwaar, onheilspellend jaar, vol gevaren, angst en dood. Je mag niet nadenken, moet van de ene dag in de andere leven, je geen zorgen maken voor morgen. Maar wie kan dat?

De dagen lengen, ’s ochtends mag je al om acht uur de verduistering verwijderen. Wat een geluk! Mijn tuintje ziet er alweer echt lenteachtig uit, het jonge groen komt bijna tevoorschijn. Het wonder der natuur ontroert me ieder jaar weer.

Zandvoort en andere plaatsen zijn nu voor ons Joden verboden, maar wie zou zin hebben om eropuit te gaan? Ook zwembaden mogen ons niet meer toelaten. Dat spijt me voor Coen en Sonja, ze houden zo van zwemmen. Maar ach, dat is het ergste niet. Als ze ons maar in onze huizen laten wonen en ons niet naar getto’s afvoeren en de mannen naar werkkampen. Hans is ook somber en zou weg willen, maar waarheen?

Vroeger dacht je dat je zorgen had. Wat waren ze in vergelijking met deze zorgen, in deze tijden? En toch houd je het hoofd koel, ben je blij dat je leeft en niet het lot van de Engelsen deelt die dagelijks in gevaar verkeren. Seyss-Inquart heeft vorige week een scherpe rede gehouden, op ons gescholden en Nederland gewaarschuwd dat bij een eventuele invasie [van de geallieerden] geen huis heel blijft.

Ook Hitler sprak in Oostenrijk dreigende, gevaarlijke woorden die geen twijfel laten bestaan over wat hij allemaal met ons van plan is. Zullen we de oorlog overleven? Vaak denk ik van niet. Mijn pessimistische woorden mag ik hier niet uitspreken, er is altijd nog hoop, maar ikzelf zie het somber in.

De voorjaarsschoonmaak staat voor de deur. De zin die er anders was, is er niet, maar iets moet er toch gebeuren. Gordijnen wassen en kasten schoonmaken. Waarom eigenlijk?

Over de onaardigheid van de kinderen wind ik me niet meer op. Ik zie minder, ben niet zo snel beledigd en ik kan het beter met ze vinden. Je leert tevredener te zijn, deze tijden leren je dat.

Belangrijkere zaken vragen om aandacht.

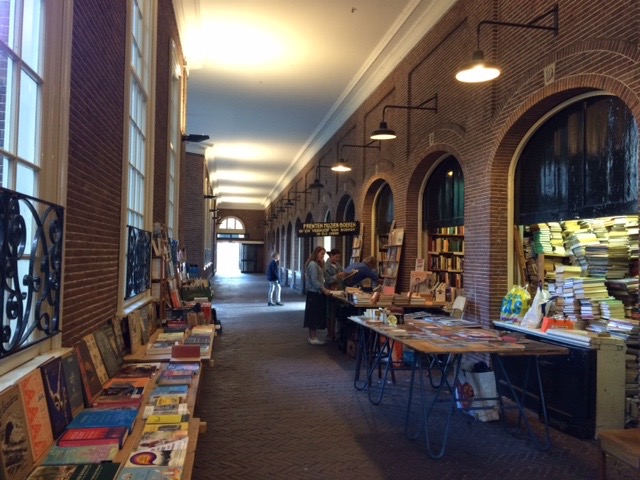

Joseph Sassoon Semah – Bushuis Oost-Indisch Huis & Duitsland Instituut

Bushuis – Ooost-Indisch Huis, UvA, Kloveniersburgwal 48, Amsterdam

Bushuis – Ooost-Indisch Huis, UvA, Kloveniersburgwal 48, Amsterdam

Installation Joseph Sassoon Semah: 24 March – 24 June 2022

Duitsland Instituut, UvA – SPUI25 – 7 april 2022, 17.00 hrs

Meeting: Footnotes accompanying the work of Joseph Beuys and Joseph Sassoon Semah

&

A Meeting with Hans Peter Riegel (Switzerland), Dr. Arie Hartog (Director Gerhard-Marcks Haus Bremen) and Joseph Sassoon Semah, under the direction of Professor Ton Nijhuis (Director DIA)

Introduction by Hans Peter Riegel, author of the four-part critical biography about Joseph Beuys, ‘Beuys, Die Biografie’, the standard reference to Beuys.

Reservation SPUI25: https://spui25.nl/programma/footnotes-to-the-work-of-joseph-beuys/make_reservation

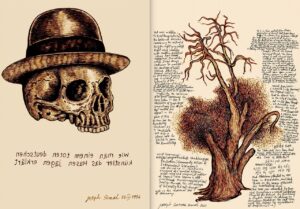

Art cannot be seen disengaged from society – which political, social and cultural implications does Joseph Beuys’ work show us? How do work and politics relate in Beuys’ work, what is myth and what is reality? Did Beuys free art of power and financial gain or did he use his art with the purpose to forget or idealize his own war history and that of Germany? Does his transformation from perpetrator to victim fit into post-war Germany? How did Beuys use his ‘visual codes’, that have disappeared, and secret symbols?

Do works of art lose their magic when the imagery is based on a myth and lies?

Do works of art lose their magic when the imagery is based on a myth and lies?

What role do the German art world and politics play to promote Joseph Beuys to one of the most important post-war artists?

How must we interpret Beuys in this celebratory year 2021/22?

‘On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV – How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist [The usefulness of continuous measurement of the distance between Nostalgia and Melancholia]’ (‘Hasenjagd’ is the code word for killing Jews during World War II) centers on Joseph Beuys and Joseph Sassoon Semah takes us on a journey of critical analysis of Beuys. Linda Bouws is the curator.

Joseph Sassoon Semah, has done extensive research into Joseph Beuys’ work, values and ideas and based on this research and texts he will analyse the deeper meaning of the (secret) symbols used by Joseph Beuys for ‘On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV- How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist [The usefulness of continuous measurement of the distance between Nostalgia and Melancholia]’. He reacts to them using new monumental sculptures and a series of old and new drawings, performances, texts and meetings.

Joseph Sassoon Semah, has done extensive research into Joseph Beuys’ work, values and ideas and based on this research and texts he will analyse the deeper meaning of the (secret) symbols used by Joseph Beuys for ‘On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV- How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist [The usefulness of continuous measurement of the distance between Nostalgia and Melancholia]’. He reacts to them using new monumental sculptures and a series of old and new drawings, performances, texts and meetings.

This project wants to raise public awareness about the missing information on Joseph Beuys.

Information that has been disregarded during this celebratory year or has been evaded to avoid uncomfortable confrontations. A new project about the reading of Beuys ‘shrouded’ art by the Jewish-Babylonian artist Joseph Sassoon Semah.

We cooperate with among others with Gerard-Marcks-Haus Bremen, Goethe-Institut Amsterdam, Duitsland Instituut Amsterdam, Deutsche Bank, Lumen Travo Gallery, Redstone Natuursteen &Projecten, Maarten Lutherkerk, Advocatenkantoor Birkway, Landgoed Nardinclant/Amsterdam Garden, Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg Amacura and The Maastricht Institute for the Arts. After completion of the manifestation a complementary publication will be compiled.

© Stichting Metropool Internationale Kunstprojecten

The project is realised in part with the support of Mondriaan Fund, the public fund for visual art and cultural heritage and Redstone Natuursteen & Projecten.

Chomsky: Peace Talks In Ukraine “Will Get Nowhere” If US Keeps Refusing To Join

As Russia steps up its assault on Ukraine and its forces advance on Kyiv, peace talks between the two sides were scheduled to resume today for the fourth time, but have now been postponed until tomorrow. Unfortunately, some opportunities for a peace agreement have already been squandered, so it’s hard to be optimistic about when the war will end. Regardless of when or how the war ends, though, its impact is already being felt across the international security system, as the rearmament of Europe shows. The Russian invasion of Ukraine also complicates the urgent fight against the climate crisis. The war takes a heavy toll on Ukraine and on the environment, but it also gives the fossil fuel industry extra leverage among governments.

In the interview that follows, world-renowned scholar and dissident Noam Chomsky shares his insights about the prospects for peace in Ukraine and how this war may impact our efforts to combat global warming.

Noam Chomsky, who is internationally recognized as one of the most important intellectuals alive, is the author of some 150 books and the recipient of scores of highly prestigious awards, including the Sydney Peace Prize and the Kyoto Prize (Japan’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize), and of dozens of honorary doctorate degrees from the world’s most renowned universities. Chomsky is Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and currently Laureate Professor at the University of Arizona.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, while a fourth round of negotiations was scheduled to take place today between Russian and Ukrainian representatives, it is now postponed until tomorrow, and it still seems unlikely that peace will be reached in Ukraine any time soon. Ukrainians don’t appear likely to surrender, and Putin seems determined to continue his invasion. In that context, what do you think of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s response to Vladimir Putin’s four core demands, which were (a) cease military action, (b) acknowledge Crimea as Russian territory, (c) amend the Ukrainian constitution to enshrine neutrality, and (d) recognize the separatist republics in eastern Ukraine?

Noam Chomsky: Before responding, I would like to stress the crucial issue that must be in the forefront of all discussions of this terrible tragedy: We must find a way to bring this war to an end before it escalates, possibly to utter devastation of Ukraine and unimaginable catastrophe beyond. The only way is a negotiated settlement. Like it or not, this must provide some kind of escape hatch for Putin, or the worst will happen. Not victory, but an escape hatch. These concerns must be uppermost in our minds.

I don’t think that Zelensky should have simply accepted Putin’s demands. I think his public response on March 7 was judicious and appropriate.

In these remarks, Zelensky recognized that joining NATO is not an option for Ukraine. He also insisted, rightly, that the opinions of people in the Donbas region, now occupied by Russia, should be a critical factor in determining some form of settlement. He is, in short, reiterating what would very likely have been a path for preventing this tragedy — though we cannot know, because the U.S. refused to try.

As has been understood for a long time, decades in fact, for Ukraine to join NATO would be rather like Mexico joining a China-run military alliance, hosting joint maneuvers with the Chinese army and maintaining weapons aimed at Washington. To insist on Mexico’s sovereign right to do so would surpass idiocy (and, fortunately, no one brings this up). Washington’s insistence on Ukraine’s sovereign right to join NATO is even worse, since it sets up an insurmountable barrier to a peaceful resolution of a crisis that is already a shocking crime and will soon become much worse unless resolved — by the negotiations that Washington refuses to join.

That’s quite apart from the comical spectacle of the posturing about sovereignty by the world’s leader in brazen contempt for the doctrine, ridiculed all over the Global South though the U.S. and the West in general maintain their impressive discipline and take the posturing seriously, or at least pretend to do so.

Zelensky’s proposals considerably narrow the gap with Putin’s demands and provide an opportunity to carry forward the diplomatic initiatives that have been undertaken by France and Germany, with limited Chinese support. Negotiations might succeed or might fail. The only way to find out is to try. Of course, negotiations will get nowhere if the U.S. persists in its adamant refusal to join, backed by the virtually united commissariat, and if the press continues to insist that the public remain in the dark by refusing even to report Zelensky’s proposals.

In fairness, I should add that on March 13, the New York Times did publish a call for diplomacy that would carry forward the “virtual summit” of France-Germany-China, while offering Putin an “offramp,” distasteful as that is. The article was written by Wang Huiyao, president of a Beijing nongovernmental think tank.

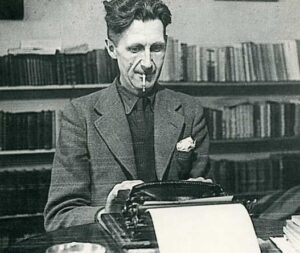

Wat kost dit boek?

George Orwell – die toen nog gewoon Eric Blair heette, het was ver voor de verschijning van Animal Farm en 1984 – werkte in 1934 en 1935 enige tijd in een boekwinkel met tweedehands boeken, tevens buurtbibliotheek. Booklover’s Corner heette de winkel, gevestigd op de hoek van South End Green in de wijk Hampstead in Londen.

Boekverkoper had Blair een ideaal beroep geleken: je verbleef de hele dag tussen boeiende literatuur, er kwamen vast en zeker interessante klanten die je kon voorzien van deskundig advies. Het viel hem vies tegen.

Ergernissen

Niet het assortiment viel hem tegen – dat was zeker aantrekkelijk – maar vooral de klanten vormden voor hem een bron van ergernis. In zijn essay Bookshop Memories vatte hij dat ongenoegen later samen: “Many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a nuisance anywhere but have special opportunities in a bookshop. For example, the dear old lady who ‘wants a book for an invalid’ (a very common demand, that), and the other old lady who read such a nice book in 1897 and wonders wether you can find her a copy. Unfortunately she doesn’t remember the title or the author’s name or what the book was about, but she does remember that it had a red cover.”(1)

Daarnaast doemden vaak figuren op, net ontstegen aan de zelfkant der samenleving, die een poging deden de handelaar waardeloze boeken te verkopen, of de types die voortdurend boeken lieten reserveren, maar niet de intentie hadden deze ooit op te halen of te betalen. En dan waren er nog de klanten die gefixeerd waren op één onderwerp en voor wie de rest van geen belang leek. Echte boekenliefhebbers, -kenners of verzamelaars leken maar een klein deel van het klantenpotentieel uit te maken. Het lijkt een probleem van alle tijden. Read more

Climate Mitigation Isn’t Just A Matter Of Ethics; It’s Life And Death

The climate crisis worsens with each passing year — and even the current levels of warming are disastrous, affecting ecosystems as well as social and environmental conditions of health. People in the world’s poorest countries remain most vulnerable to the crisis. The world’s governments are slow to react to the greatest challenge facing humanity today, even though potential solutions are not in short supply, with the transition to a green economy offering the most effective pathway to tackling the problem of global warming at its roots.

There are, in addition, intermediate steps that can be taken toward climate stabilization, such as carbon pricing and even the adoption of a universal basic income scheme as a means to counter the effects of global warming. Meanwhile, policy frameworks for climate adaptation are urgently needed, as renowned economist James K. Boyce points out in this interview. Boyce is professor emeritus of economics and senior fellow at the Political Economy Research Institute of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He received his PhD in economics from Oxford University and is the author of scores of books, including, most recently, The Case for Carbon Dividends (2019) and Economics for People and the Planet (2021). He received the 2017 Leontief Prize for Advancing the Frontiers of Economic Thought.

C.J. Polychroniou: The climate crisis is the biggest problem facing humanity in the 21st century. In the effort to avoid a greenhouse apocalypse, competing approaches to climate action have been advanced, ranging from outright technological solutions to an economic and social revolution as envisioned in the Green New Deal project and everything in between. Two of those “in between” approaches for cutting carbon emissions are cap-and-trade, a system already implemented in the state of California, and carbon pricing and carbon dividends, which is the approach you are advocating. Why do we need to put a price on carbon? How does carbon pricing work, and what are its benefits?

James K. Boyce: First, let me say that I do not think it is useful to invoke the language of a coming “apocalypse.” It’s a vision with a lot of historical baggage, much of it downright reactionary, as my partner Betsy Hartmann explains in her book, The America Syndrome: War, Apocalypse, and Our Call to Greatness (Seven Stories Press, 2019). It misrepresents the climate crisis as a cliff edge, an all-or-nothing question akin to nuclear war, as opposed to an unfolding process that has ever-worsening consequences for humans and other living things. And it can instill a sense of despair and hopelessness that is deeply counterproductive. I agree with the late Raymond Williams that the task of the true radical is “to make hope possible, not despair convincing.”

Something similar can be said about the contrast between technological fixes and revolutionary transformations. Economic and social revolution is a process, too, not a one-off affair. Technological change can help to propel institutional change, and vice versa, and often there is an intimate connection between the two. I do not think we will solve the climate crisis with new technologies alone. The transition to a clean energy economy will require profound changes not only in how we relate to the natural world but also in how we relate to each other. I have argued that it will require a narrowing of inequalities and a deepening of democracy. But it would be folly to sit aside, waiting for social and economic revolution, before tackling the climate problem.

Cap-and-trade and carbon dividend policies both put a price on carbon. Instead of being able to dump carbon into the atmosphere free of charge (more precisely, free of monetary charge, since nature is charging us big time), pollution would carry a price tag. But there are crucial differences between these two policies. Cap-and-trade gives free pollution permits to corporations, up to the limit set by the cap. Consumers feel the bite in higher prices for transportation fuels, heating and electricity, just as they do when the oil cartel restricts supplies. The extra money they pay goes as windfall profits into the coffers of the corporations that received free permits. This may blunt political opposition to a carbon price from fossil fuel lobbyists, but their first preference remains no cap at all, as was shown in the repeat debacles of efforts to pass cap-and-trade bills in Washington, D.C. in the first decade of the century.

Carbon dividend policies put a price on carbon, too, either via a cap with auctioned (not free) permits or by means of a tax. But instead of fueling windfall profits, the money from higher prices goes directly back to the public in equal per-person payments, consistent with the principle that we all own the gifts of nature — in this case, the limited capacity of the biosphere to absorb carbon emissions — in common and equal measure. As I discuss in my book, The Case for Carbon Dividends (Polity Press, 2019), this is an example of universal property. The right to receive carbon dividends cannot be bought or sold, or accumulated in a few hands, or owned by corporations. Universal property is individual, inalienable and perfectly egalitarian. This new kind of property, which is more akin to traditional common property than to private property or state property, could be a cornerstone for what is sometimes called “libertarian socialism.”

It’s not that we simply need to put a price — any price — on carbon, although anything is better than the prevailing de facto price of zero. What we need to do is to keep the fossil fuels in the ground, to curtail their extraction at a pace and scale ambitious enough to stabilize the Earth’s climate by the middle of the century. This is the goal of the Paris Agreement. In practice, it means that high-consuming countries, like the United States, must cut their use of fossil fuels by about 8 or 9 percent per year, year after year, between now and 2050. The easiest way to arrive at the “right” price on carbon is to cap the amount of fossil fuels we allow to enter our economy to meet this trajectory. For each ton of carbon they sell, fossil fuel firms would have to surrender a permit. They would buy permits (up to the limit set by the cap that tightens over time) at auctions. This is not rocket science. Quarterly auctions have been held since 2009 under the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative for power plants in the northeastern states of the U.S. The carbon price comes about as a side effect of keeping fossil fuels in the ground, not as an end in itself.

n addition to climate stabilization, a side benefit of carbon dividends is that they would take a modest step toward reducing economic inequality, which has reached obscene levels in the U.S. and many other countries. Most households would come out ahead financially with carbon dividends, receiving more in dividends than they pay in higher fuel prices, for the simple reason that their carbon footprints are smaller than average. High-income households with their outsized consumption of carbon, and everything else, would pay more than they get back, but they can afford it.

You have also argued for a universal basic income as a solution to inequality and the effects of global warming. How would a universal income be funded, and would it be an addition to existing welfare programs or a replacement for them?

Correction: Universal basic income can be part of the solution. Guaranteed employment can also be part of the solution, and as my colleagues Bob Pollin and his coauthors have shown, the clean energy transition will generate millions of jobs. The extent to which existing welfare programs become redundant would depend on how much money we’re talking about. A big advantage of universal income, compared to means-tested welfare payments, is that it unites society rather than dividing it between the welfare-eligible poor and everyone else. Universality helps to ensure political durability, as we’ve seen with Social Security and Medicare here in the U.S.

For universal basic income, a key question is how to pay for it. Most proposals rely on government funding. But redistributive taxation can be a heavy lift, and its durability is never certain since it depends on the vagaries of party politics. This is one reason I favor universal property as a source of universal basic income [universal property refers to the idea of a universal birthright to an equal share of co-inherited wealth]. Carbon dividends are one example. In his new book, Ours: The Case for Universal Property (Polity Press, 2021), Peter Barnes discusses a number of other possibilities.

We now know that dramatic mass climate catastrophe is inevitable, especially for mega-cities and coastal populations. What are the sorts of changes (involving migration, changes in how cities are structured, changes in how nations relate to each other, technologies, etc.) that could help humans as a global community weather these catastrophes without massive human deaths? And what are the sorts of pressures and dynamics (protests, legislation, international cooperation) that would actually make these changes imaginable to implement in time?

Every year that passes without serious policies to keep fossil carbon in the ground, where it belongs, increases the suffering that climate change will inflict. Coastal populations will be among the most seriously affected, but they will not be alone. Drought-prone regions in Africa, for example, are at grave risk, too.

Not long ago, proponents of action to halt climate change (“mitigation” in the official lingo), including many governments in the Global South, were averse to discussing adaptation, fearing that it would let the big polluters off the mitigation hook. Times have changed. Today, the need for adaptation is urgent and undeniable. The key questions are how adaptation resources will be allocated across and within countries, and who will foot the bill.

Noam Chomsky: A No-Fly Zone Over Ukraine Could Unleash Untold Violence

As war rages on in Ukraine, diplomacy continues to take a back seat in spite of the heartbreaking devastation Russia’s invasion has wrought. The post-World War II global architecture is simply incapable of regulating issues of war and peace, and the West continues to reject Russia’s security concerns. Moreover, there are calls in some quarters for a declaration of a no-fly zone over Ukraine, although the actual enforcement of such a policy would quickly escalate violence, with potential consequences nearly too horrible to speak. The idea of a no-fly zone is profoundly dangerous, warns Noam Chomsky in this exclusive interview for Truthout.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, nearly two weeks into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian forces continue to pummel cities and towns while more than 140 countries voted in favor of a UN nonbinding resolution condemning the invasion and calling for a withdrawal of Russian troops. In light of Russia’s failure to comply with rules of international law, isn’t there something to be said at the present juncture about the institutions and norms of the postwar international order? It’s quite obvious that the Westphalian state-centric world order cannot regulate the geopolitical behavior of state actors with respect to issues of war/peace and even sustainability. Isn’t it therefore a matter of survival that we develop a new global normative architecture?

Noam Chomsky: If it really is literally a matter of survival, then we are lost, because it cannot be achieved in any relevant time frame. The most we can hope for now is strengthening what exists, which is very weak. And that will be hard enough.

The great powers constantly violate international law, as do smaller ones when they can get away with it, commonly under the umbrella of a great power protector, as when Israel illegally annexes the Syrian Golan Heights and Greater Jerusalem — tolerated by Washington, authorized by Donald Trump, who also authorized Morocco’s illegal annexation of Western Sahara.

Under international law, it is the responsibility of the UN Security Council to keep the peace and, if deemed necessary, to authorize force. Superpower aggression doesn’t reach the Security Council: U.S. wars in Indochina, the U.S.-U.K. invasion of Iraq, or Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, to take three textbook examples of the “supreme international crime” for which Nazis were hanged at Nuremberg. More precisely, the U.S. is untouchable. Russian crimes at least receive some attention.

The Security Council may consider other atrocities, such as the French-British-Israeli invasion of Egypt and the Russian invasion of Hungary in 1956. But the veto blocks further action. The former was reversed by orders of a superpower (the U.S.), which opposed the timing and manner of the aggression. The latter crime, by a superpower, could only be protested.

Superpower contempt for the international legal framework is so common as to pass almost unnoticed. In 1986, the International Court of Justice condemned Washington for its terrorist war (in legalistic jargon, “unlawful use of force”) against Nicaragua, ordering it to desist and pay substantial reparations. The U.S. dismissed the judgment with contempt (with the support of the liberal press) and escalated the attack. The UN Security Council did try to react with a resolution calling on all nations to observe international law, mentioning no one, but everyone understood the intention. The U.S. vetoed it, proclaiming loud and clear that it is immune to international law. It has disappeared from history.

It is rarely recognized that contempt for international law also entails contempt for the U.S. Constitution, which we are supposed to treat with the reverence accorded to the Bible. Article VI of the Constitution establishes the UN Charter as “the supreme law of the land,” binding on elected officials, including, for example, every president who resorts to the threat of force (“all options are open”) — banned by the Charter. There are learned articles in the legal literature arguing that the words don’t mean what they say. They do.

It’s all too easy to continue. One outcome, which we have discussed, is that in U.S. discourse, including scholarship, it is now de rigueur to reject the UN-based international order in favor of a “rule-based international order,” with the tacit understanding that the U.S. effectively set the rules.

Even if international law (and the U.S. Constitution) were to be obeyed, its reach would be limited. It would not reach as far as Russia’s horrendous Chechnya wars, levelling the capital city of Grozny, perhaps a hideous forecast for Kyiv unless a peace settlement is reached; or in the same years, Turkey’s war against Kurds, killing tens of thousands, destroying thousands of towns and villages, driving hundreds of thousands to miserable slums in Istanbul, all strongly supported by the Clinton administration which escalated its huge flow of arms as the crimes increased. International law does not bar the U.S. specialty of murderous sanctions to punish “successful defiance,” or stealing the funds of Afghans while they face mass starvation. Nor does it bar torturing a million children in Gaza or a million Uighurs sent to “re-education camps.” And all too much more.

How can this be changed? Not much is likely to be achieved by establishing a new “parchment barrier,” to borrow James Madison’s phrase, referring to mere words on paper. A more adequate framework of international order may be useful for educational and organizing purposes — as indeed international law is. But it is not enough to protect the victims. That can only be achieved by compelling the powerful to cease their crimes — or in the longer run, undermining their power altogether. That’s what many thousands of courageous Russians are doing right now in their remarkable efforts to impede Putin’s war machine. It is what Americans have done in protesting the many crimes of their state, facing much less serious repression, with good effect even if insufficient.

Steps can be taken to construct a less dangerous and more humane world order. For all its flaws, the European Union is a step forward beyond what existed before. The same is true of the African Union, however limited it remains. And in the Western hemisphere, the same is true for such initiatives as UNASUR [the Union of South American Nations] and CELAC [the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States], the latter seeking Latin American-Caribbean integration separate from the U.S.-dominated Organization of American States.

The questions arise constantly in one or another form. Up to virtually the day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the crime very possibly could have been averted by pursuing options that were well understood: Austrian-style neutrality for Ukraine, some version of Minsk II federalism reflecting the actual commitments of Ukrainians on the ground. There was little pressure to induce Washington to pursue peace. Nor did Americans join in the worldwide ridicule of the odes to sovereignty on the part of the superpower that is in a class by itself in its brutal disdain for the notion.

The options still remain, though narrowed after the criminal invasion.

- Page 2 of 3

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- next page