Democrats Didn’t Win – They Simply Held The Line

Americans invested in the idea of living in a democracy heaved a collective sigh of relief the day after the 2022 midterm elections when it became clear that the dire predictions of a Republican sweep were overblown. Democrats made greater gains than expected, winning races in both the Senate and the House that they didn’t expect to.

It happened because masses of people cast ballots, defying long-standing historical trends of low midterm turnout. Voters almost matched the high turnout of the 2018 elections when outrage over Donald Trump’s first two years in office pushed Congress into the hands of Democrats. Stung by their opposition’s showing and by Trump’s reelection loss two years later, Republicans ramped up voter suppression efforts, hoping to blunt the impact of an increasingly young, diverse, and enthusiastic electorate.

Liberal-leaning voters showed up to the polls during this latest midterm election largely in response to the overturning of abortion rights, but also to stave off right-wing extremism.

Although the worst did not come to pass during the midterms, simply holding the line against a descent into fascism is not enough. Republicans are wresting control of the nation’s steering wheel as hard as they can and forcing it as far right as possible. Their party has divested itself from democratic norms and thrown its weight behind Trump and his lies. They have invested in stripping people of their bodily autonomy and fashioning a dangerous world ruled by force and a riotous mob mentality. Much more is needed in the face of such hubris: Fascists need to be placed on the defensive, and a split Congress is not enough to do so.

Three major factors explain why Democrats didn’t win outright control of both congressional chambers: First, Republicans have aggressively reduced the impact of Democratic votes; second, Democrats were unable or unwilling to articulate a clear message of why their agenda is better than that of the Republicans; and third, the corporate media refused to center people’s well-being in their framing of election-related issues.

Republicans have played the long game on suppressing democracy, redrawing district maps for years in order to favor their candidates and appointing conservative, partisan judges into federal courts to affirm those maps. They have done so in tandem with a slew of voter suppression laws in states they control—which is the majority. Analilia Mejia, co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy Action, says in an interview that such efforts are “a strategy utilized to negate the power of a rising Black and Brown electorate.”

The GOP is also terrified (or should be) of young people voting. Recall in the 2016 presidential race when Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump was blamed, in part, on younger voters who weren’t motivated to show up to the polls. Two years later, that trend was reversed in the first midterms of Trump’s presidency. Now, four years after that, young voters have realized the dangers of apathy and showed up to the polls in force, casting a majority of their ballots for Democrats.

Mejia says “the policies that really motivate people” to vote are “the policies that we know will essentially save humanity and the planet and stop climate change; the policies that we know will ensure that our children, that our elders, that those most vulnerable in our communities have the resources that they need to not only survive but thrive—[these] are policies that are supported by the vast majority of people.”

This—including the overturning of abortion rights at the Supreme Court—was precisely what motivated so many young people and people of color to vote in the 2022 midterms. Varshini Prakash, executive director and co-founder of the Sunrise Movement, a youth climate justice organization, told Common Dreams, “For us, it’s never been just about defeating Donald Trump… We turn out to fight for the issues our generation faces every day, like the impending climate crisis, protecting our reproductive freedoms, and ending gun violence in our schools.”

And yet, climate justice, economic justice, and racial justice were largely missing from the story that Democrats told in order to motivate people to go to the polls.

Rather than tout how his administration and his party would ensure a just transition to renewable fuels, President Joe Biden was fixated on gas prices and how to lower them. Instead of showcasing how the 2021 American Rescue Plan was a good example of federal government action on inequality, candidates running for office were on the defensive against Republicans’ and the media’s hammering of inflation as a central election issue. In contrast to their 2020 promises to tackle racist police brutality and mass incarceration, Democrats decided to pass a bill to increase police funding and stave off GOP accusations of being “soft on crime.”

Voters showed up in spite of this. But they may have shown up to elect Democrats in even higher numbers had climate, economic, and racial justice been front and center ahead of the midterms. “These are popular ideas,” says Mejia.

Not only did Democrats refuse to fully articulate these popular ideas, but the corporate media also shaped its coverage to suit the GOP’s agenda. Outlets aggressively played up the Republican Party’s line that inflation was the central issue of the election—one for which, they alleged, Democrats bore sole blame.

Take one New York Times article published on Election Day. “Inflation is almost certainly the issue pushing the economy to its current prominence,” wrote the Times’ economic reporter Jeanna Smialek in a story headlined, “Inflation Plagues Democrats in Polling. Will It Crush Them at the Ballot Box?” Just hours after it was published, such a confident claim fell apart as the Democrats were most certainly not “crushed” at the ballot box.

Mainstream U.S. corporate news media outlets could have taken a page out of their British counterpart’s book, the Guardian, which publishes analyses like that of former U.S. labor secretary Robert Reich. “Corporations are using rising costs as an excuse to increase their prices even higher, resulting in record profits,” wrote Reich, offering an explanation for inflation largely missing from U.S. outlets.

One Wall Street Journal article went as far as explaining quite convincingly that rather than being sparked by Democrats’ policies, inflation was triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, and that the U.S. was in line with other nations and with historical trends. Yet the Journal couldn’t resist framing the piece with the misleading headline: “Midterm Election Could Make Democrats Latest Governing Party to Pay Price for Inflation.”

Most U.S. newspapers have spent the past year banging the drum of inflation and exaggerating its impact. They have accepted the dogma that higher wages, lower unemployment, and government assistance are the source of rising prices rather than corporate greed.

Mejia is aghast at the consensus that is emerging to tackle inflation through increasing interest rates and slashing benefits. She finds it “unbelievable that the way we dig ourselves… out of an economic crisis is by inflicting strategic targeted and sustained pain to those who are most vulnerable.”

She says that “the only way out of here, out of this moment, is through investment in people, in civic participation, and increasing our political power and voice.”

Perhaps if the Democratic Party had centered its midterm platform on such an approach, and perhaps if the corporate media had not distorted the truth, victory would not have been defined by simply holding the line against a fascist GOP; it would have been—and could have been—an outright defeat of authoritarianism and injustice. Too much is at stake, and our standards of success cannot be low.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

What Was Humanity’s First Cultural Revolution?

We live in a fast-moving, technology-dominated era. Happiness is fleeting, and everything is replaceable or disposable. It is understandable that people are drawn to a utopian vision. Many find refuge in the concept of a “return” to an idealized past—one in which humans were not so numerous, and animals abounded; when the Earth was still clean and pure, and when our ties to nature were unviolated.

But this raises the question: Is this nothing more than a utopian vision? Can we pinpoint a time in our evolutionary trajectory when we wandered from the path of empathy, of compassion and respect for one another and for all forms of life? Or are we nihilistically the victims of our own natural tendencies, and must we continue to live reckless lifestyles, no matter the outcome?

Studying human prehistory enables people to see the world through a long-term lens—across which we can discern tendencies and patterns that can only be identified over time. By adopting an evolutionary outlook, it becomes possible to explain when, how, and why specific human traits and behaviors emerged.

The particularity of human prehistory is that there are no written records, and so we must try to answer our questions using the scant information provided for us by the archeological record.

The Oldowan era that began in East Africa can be seen as the start of a process that would eventually lead to the massive technosocial database that humanity now embraces and that continues to expand ever further in each successive generation, in a spiral of exponential technological and social creativity. The first recognizable Oldowan tool kits start appearing 2.6 million years ago; they contain large pounding implements, alongside small sharp-edged flakes that were certainly useful for, among other things, obtaining viscera and meat resources from animals that were scavenged as hominins (humans and their close extinct ancestors) competed with other large carnivores present in their environments. As hominins began to expand their technological know-how, successful resourcing of such protein-rich food was ideal for feeding the developing and energy-expensive brain.

Stone tool production—and its associated behaviors—grew ever more complex, eventually requiring relatively heavy investments into teaching these technologies to successfully pass them onward into each successive generation. This, in turn, established the foundations for the highly beneficial process of cumulative learning that became coupled with symbolic thought processes such as language, ultimately favoring our capacity for exponential development.

This had huge implications, for example, in terms of the first inklings of what we call “tradition”—ways to make and do things—that are indeed the very building blocks of culture. Underpinning this process, neuroscientific experiments carried out to study the brain synapses and areas involved during toolmaking processes show that at least some basic forms of language were likely needed in order to communicate the technologies required to manufacture the more complex tools of the Acheulian age that commenced in Africa about 1.75 million years ago. Researchers have demonstrated that the areas of the brain activated during toolmaking are the same as those employed for abstract thought processes, including language and volumetric planning.

When we talk about the Acheulian, we are referring to a hugely dense cultural phenomenon occurring in Africa and Eurasia that lasted some 1.4 million years. While it cannot be considered a homogenous occurrence, it does entail a number of behavioral and technosocial elements that prehistorians agree tie it together as a sort of unit.

Globally, the Acheulian technocomplex coincides generally with the appearance of the relatively large-brained hominins attributed to Homo erectus and the African Homo ergaster, as well as Homo heidelbergensis, a wide-ranging hominin identified in Eurasia and known to have successfully adapted to relatively colder climatic conditions. Indeed, it was during the Acheulian that hominins developed fire-making technologies and that the first hearths appear in some sites (especially caves) that also show indications of seasonal or cyclical patterns of use.

In terms of stone tool technologies, Acheulian hominins moved from the nonstandardized tool kits of the Oldowan to innovate new ways to shape stone tools that involved comparatively complex volumetric concepts. This allowed them to produce a wide variety of preconceived flake formats that they proceeded to modify into a range of standardized tool types. Conceptually, this is very significant because it implies that for the first time, stone was being modeled to fit with a predetermined mental image. The bifacial and bilateral symmetry of the emblematic Acheulian tear-shaped handaxes is especially exemplary of this particular hallmark.

The Acheulian archeological record also bears witness to a whole new range of artifacts that were manufactured according to a fixed set of technological notions and newly acquired abilities. To endure, this toolmaking know-how needed to be shared by way of ever more composite and communicative modes of teaching.

We also know that Acheulian hominins were highly mobile since we often find rocks in their tool kits that were imported from considerable distances away. Importantly, as we move through time and space, we observe that some of the tool making techniques actually show special features that can be linked to specific regional contexts. Furthermore, population densities increased significantly throughout the period associated with the later Acheulian phenomenon—roughly from around 1 million to 350,000 years ago—likely as a result of these technological achievements.

Beyond toolmaking, other social and behavioral revolutions are attributed to Acheulian hominins. Fire-making, whose significance as a transformative technosocial tool cannot be overstated, as well as other accomplishments, signal the attainment of new thresholds that were to hugely transform the lives of Acheulian peoples and their descendants. For example, Acheulian sites with evidence of species-specific hunting expeditions and systematized butchery indicate sophisticated organizational capacities and certainly also suggest that these hominins mastered at least some form of gestural—and probably also linguistic—communication.

All of these abilities acquired over thousands of years by Acheulian peoples enabled them not only to settle into new lands situated, for example, in higher latitudes, but also to overcome seasonal climatic stresses and so to thrive within a relatively restricted geographical range. While they were certainly nomadic, they established home-base type living areas to which they returned on a cyclical basis. Thus, the combined phenomena of more standardized and complex culture and regional lifeways led these ancient populations to carve out identities even as they developed idiosyncratic technosocial behaviors that gave them a sense of “belonging” to a particular social unit—living within a definable geographical area. This was the land in which they ranged and into which they deposited their dead (intentional human burials are presently only recognized to have occurred onward from the Middle Paleolithic). To me, the Acheulian represents the first major cultural revolution known to humankind.

So I suggest that it was during the Acheulian era that increased cultural complexity led the peoples of the world to see each other as somehow different, based on variances in their material culture. In the later Acheulian especially, as nomadic groups began to return cyclically to the same dwelling areas, land-linked identities formed that I propose were foundational to the first culturally based geographical borders. Through time, humanity gave more and more credence to such constructs, deepening their significance. This would eventually lead to the founding of modern nationalistic sentiments that presently consolidate identity-based disparity, finally contributing to justifying geographic inequality of wealth and power.

Many of the tough questions about human nature are more easily understood through the prism of prehistory, even as we make new discoveries. Take, for instance, the question of where the modern practice of organized violence emerged from.

Human prehistory, as backed by science, has now clearly demonstrated that there is no basis for dividing peoples based on biological or anatomical aspects and that warlike behaviors involving large numbers of peoples, today having virtually global effects on all human lives, are based on constructed imaginary ideologies. Geographical boundaries, identity-based beliefs, and religion are some of the conceptual constructs commonly used in our world to justify such behaviors. In addition, competition buttressed by concepts of identity is now being accentuated due to the potential and real scarcity of resources resulting from population density, consumptive lifestyles, and now also accelerated climate change.

On the question of whether or not the emergence of warlike behavior was an inevitable outcome, we must observe such tendencies from an evolutionary standpoint. Like other genetic and even technological traits, the human capacity for massive violence exists as a potential response that remains latent within our species until triggered by particular exterior factors. Of course, this species-specific response mode also corresponds with our degree of technological readiness that has enabled us to create the tools of massive destruction that we so aptly manipulate today.

Hierarchized societies formed and evolved throughout the Middle and Late Pleistocene when a range of hominins coevolved with anatomically modern humans that we now know appeared in Africa as early as 300,000 years ago. During the Holocene Epoch, human links to specific regional areas were strengthened even further by the sedentary lifestyles that developed into the Neolithic period, as did the inclination to protect the resources amassed in this context. We can conjecture the emergence of a wide range of sociocultural situations that would have arisen once increasing numbers of individuals were arranged into the larger social units permitted by the capacity to produce, store, and save sizable quantities of foodstuffs and other kinds of goods.

Even among other animals, including primates, increased population densities result in competitive behaviors. In this scenario, that disposition would have been intensified by the idea of accumulated goods belonging, as it were, to the social unit that produced them.

Bringing technology into play, we can clearly see how humans began to transform their know-how into ingenious tools for performing different acts of warfare. In the oldest tool kits known to humankind going back millions of years, we cannot clearly identify any artifacts that appear adequate to be used for large-scale violence. We don’t have evidence of organized violence until millions of years after we started developing tools and intensively modifying the environments around us. As we amplified the land-linked identity-based facet of our social lives, so did we continue to develop ever more efficient technological and social solutions that would increase our capacity for large-scale warfare.

If we can understand how these behaviors emerged, then we can also use our technological skills to get to the root of these problems and employ all we have learned to finally take a better hold of the reins of our future.

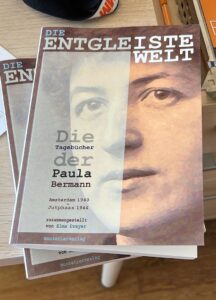

Paula Bermann – Die entgleiste Welt. Die Tagebücher Amsterdam 1940 – Jutphaas 1944

Jetzt erschienen!

Paula Bermann – Die entgleiste Welt – Die Tagebücher der Paula Bermann. Amsterdam 1940 – Jutphaas 1944

Die deutsche Jüdin Paula Bermann, die in den Niederlanden beheimatet war, führte von 1940 bis 1944 ein Tagebuch. Das Tagebuch ist ein beklemmender Bericht über die Welt im Krieg, ihre niederländische Familie, ihre Familie in Deutschland und das heraufziehende Elend einer systematischen Vernichtung alles Jüdischen.

Sie ist politisch sehr gut informiert und beschreibt detailliert den Alltag in Amsterdam und ab 1942 aus dem Versteck in Jutphaas. Zwischen den Zeilen sind ihre Ängste und Sehnsüchte und ihre Abneigung gegen eine aufgezwungene Identität zu lesen: sowohl deutsch als auch jüdisch. Als Deutsche wird sie misstrauisch beäugt, als Jüdin gejagt. Bermanns Tagebucheinträge sind durchdrungen von Melancholie, Wut, Sorge um ihre Kinder, Abneigung gegen ihre Landsleute und Angst vor Verrat. Noch nie hat es eine so leidenschaftliche und präzise Beschreibung eines Lebens in den besetzten Niederlanden gegeben, geschrieben von einer deutschen Jüdin.

Das Tagebuch endet abrupt: Im Frühjahr 1944 werden Paula, ihr Mann Coen und ihre Tochter Inge verraten, verhaftet und über Westerbork nach Bergen-Belsen deportiert. Kurz vor der Befreiung sterben Paula und Coen. Ihre drei Kinder überleben den Krieg.

Musketier Verlag, Bremen, 2022. 264 Seiten. ISBN 9783946635673. Euro 24,90

https://www.musketierverlag.com/die-tagebucher-der-paula-bermann

Kontakt: info@musketier-verlag.de

Refseek

RefSeek is a web search engine for students and researchers that aims to make academic information easily accessible to everyone. RefSeek searches more than five billion documents, including web pages, books, encyclopedias, journals, and newspapers.

RefSeek is a web search engine for students and researchers that aims to make academic information easily accessible to everyone. RefSeek searches more than five billion documents, including web pages, books, encyclopedias, journals, and newspapers.

RefSeek‘s unique approach offers students comprehensive subject coverage without the information overload of a general search engine—increasing the visibility of academic information and compelling ideas that are often lost in a muddle of sponsored links and commercial results.

How can we better serve you or your students? We’d love to hear from you! Please send comments, inquiries, and suggestions using our contact form.

Lula Must Save Brazil From Savage Capitalism, Says Federal Deputy Juliana Cardoso

Juliana Cardoso is sitting in her office in front of a lavender, orange, and yellow mandala that was made for her. She has been a member of São Paulo’s city council since 2008. On October 2, 2022, as a candidate for the Workers Party (PT), Cardoso won a seat in Brazil’s lower house, the Federal Chamber of Deputies.

She is wearing a t-shirt that bears the powerful slogan: O Brasil é terra indígena (Brazil is Indigenous land). The slogan echoes her brave campaign against the disregard shown by Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s 38th president defeated on October 30, towards the Indigenous populations of his country. In 2020, during the height of the pandemic, Bolsonaro vetoed Law no. 14021 which would have provided drinking water and basic medical materials to Indigenous communities. Several organizations took Bolsonaro to the International Criminal Court for this action.

In April 2022, Cardoso wrote that the rights of the Indigenous “did not come from the kindness of those in power, but from the struggles of Indigenous people over the centuries. Though guaranteed in the [1988] Constitution, these rights are threatened daily.” Her political work has been defined by her commitment to her own Indigenous heritage but also by her deep antipathy to the “savage capitalism” that has cannibalized her country.

Savage Capitalism

Bolsonaro had accelerated a project that Cardoso told us was an “avalanche of savage capitalism. It is a capitalism that kills, that destroys, that makes a lot of money for a few people.” The current beneficiaries of this capitalism refuse to recognize that the days of their unlimited profits are nearly over. These people—most of whom supported Bolsonaro—“live in a bubble of their own, with lots of money, with swimming pools.” Lula’s election victory on October 30 will not immediately halt their “politics of death,” but it has certainly opened a new possibility.

New studies about poverty in Brazil reveal startling facts. An FGV Social study from July 2022 found that almost 63 million Brazilians—30% of the country’s population—live below the poverty line (10 million Brazilians slipped below that line to join those in poverty between 2019 and 2021). The World Bank documented the spatial and racial divides of Brazil’s poverty: three in ten of Brazil’s poor are Afro-Brazilian women in urban areas, while three-quarters of children in poverty live in rural areas. President Bolsonaro’s policies of upward redistribution of wealth during the pandemic and after contributed to the overall poverty in the country and exacerbated the deep social inequalities of race and region that already existed. This, Cardoso says, is evidence of the “savage capitalism” that has gripped her country and left tens of millions of Brazilians in a “hole, with no hope of living.”

To Sow Hope

“I was born and raised within the PT,” she tells us, in the Sapopemba area of São Paulo. Surrounded by the struggles against “savage capitalism,” Cardoso was raised by parents who were active in the PT. “As a girl, I walked amongst those who built the PT, such as José Dirceu, José Genoino, President Lula himself,” as well as her mother—Ana Cardoso, who was one of the founders of the PT. Her parents—Ana Cardoso and Jonas “Juruna” Cardoso—were active in the struggles of the metalworkers and for public housing in the Fazenda da Juta area of Sapopemba. A few days after he led a protest in 1985, Juruna was shot to death by mysterious gunmen. Juliana had been sitting in his lap outside their modest home in the COHAB Teotônio Vilela. Her mother was told not to insist on an investigation, since this would “bring more deaths.” This history of struggle defines Juliana.

“We are not bureaucrats,” she told us. “We are militants.” People like her who will be in the Congress will “use the instrument of the mandate to move an agenda” to better the conditions of everyday life. Pointing to the mandala in her office, Juliana says, “I think this lilac part is my shyness.” Her active life in politics, she says, “kind of changed me from being shy to being much firmer.” There is only one reason “why I am here,” she says, and that is “to sow, to have hope for seeds that will fight with me for the working class, for women, during this difficult class struggle.”

Politics in Brazil is Violent

Lula will be sworn into office on January 1, 2023. He will face a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate that are in the grip of the right-wing. This is not a new phenomenon, although the centrão (centre), the opportunistic bloc in the parliament that has run things, will now have to work alongside far-right members of Bolsonaro’s movement. Juliana and her left allies will be in a minority. The right, she says, enters politics with no desire to open a dialogue about the future of Brazil. Many right-wing politicians are harsh, formed by fake news and a suffocating attitude to money and religion. “Hate, weapons, death”—these are the words that seem to define the right-wing in Brazil. It is because of them that politics “is very violent.”

Juliana entered politics through struggles developed by the Base Ecclesiastical Communities (CEBs) of the Catholic Church, learning her ethics through Liberation Theology through the work of Dom Paulo Evaristo Arns and Paulo Freire. “You have to engage people in their struggles, dialogue with them about their struggles,” she told us. This attitude to building struggles and dialoguing with anyone defines Juliana as she prepares to go to Brasilia and take her seat in the right-wing dominated National Congress.

Lula, Juliana says, “is an ace.” Few politicians have his capacity to dialogue with and convince others about the correctness of his positions. The left is weak in the National Congress, but it has the advantage of Lula. “President Lula will need to be the big star,” said Juliana. He will have to lead the charge to save Brazil from savage capitalism.

Japan’s Discomfort In The New Cold War

In early December 2021, Japan’s Self-Defense Force joined the U.S. armed forces for Resolute Dragon 2022, which the U.S. Marines call the “largest bilateral training exercise of the year.” Major General Jay Bargeron of the U.S. 3rd Marine Division said at the start of the exercise that the United States is “ready to fight and win if called upon.” Resolute Dragon 2022 followed the resumption in September of trilateral military drills by Japan, South Korea, and the United States off the Korean peninsula; these drills had been suspended as the former South Korean government attempted a policy of rapprochement with North Korea.

These military maneuvers take place in the context of heightened tension between the United States and China, with the most recent U.S. National Security Strategy identifying China as the “only competitor” of the United States in the world and therefore in need of being constrained by the United States and its allies (which, in the region, are Japan and South Korea). This U.S. posture comes despite repeated denials by China—including by Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian on November 1, 2022—that it will “never seek hegemony or engage in expansionism.” These military exercises, therefore, place Japan center-stage in the New Cold War being prosecuted by the United States against China.

Article 9

The Constitution of Japan (1947) forbids the country from building up an aggressive military force. Two years after Article 9 was inserted into the Constitution at the urging of the U.S. Occupation, the Chinese Revolution succeeded and the United States began to reassess the disarmament of Japan. Discussions about the revocation of Article 9 began at the start of the Korean War in 1950, with the U.S. government putting pressure on Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida to build up the army and militarize the National Police Reserve; in fact, the Ashida Amendment to Article 9 weakened Japan’s commitment to demilitarization and left open the door to full-scale rearmament.

Public opinion in Japan is against the formal removal of Article 9. Nonetheless, Japan has continued to build up its military capacity. In the 2021 budget, Japan added $7 billion (7.3%) to spend $54.1 billion on its military, “the highest annual increase since 1972,” notes the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. In September 2022, Japan’s Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada said that his country would “radically strengthen the defense capabilities we need….To protect Japan, it’s important for us to have not only hardware such as aircrafts and ships, but also enough ammunition for them.” Japan has indicated that it would increase its military budget by 11% a year from now till 2024.

In December, Japan will release a new National Security Strategy, the first since 2014. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida told the Financial Times, “We will be fully prepared to respond to any possible scenario in east Asia to protect the lives and livelihoods of our people.” It appears that Japan is rushing into a conflict with China, its largest trading partner.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power>

Source: Globetrotter