Do Grandmothers Hold The Key To Understanding Human Evolution?

Brenna R. Hassett – Photo: en.wikipedia.org

Of the innumerable species on the planet, just a bare handful have evolved to have one of the most counterintuitive adaptations possible. In a small number of animals, all big-brained mammals, we see something that should not, at first glance, be of adaptive value: animals that have lived past the ability to reproduce. This is so clearly contra the main aim of any living species, which is to survive and reproduce, that evolutionary biology has been forced into entirely new theoretical directions in order to explain one of the most baffling phenomena in science: grandmothers.

Why should grandmothers cause such a stir? As humans, we tend to think of them as a natural part of life—and women who are past reproductive age are in fact a critical part of our societies. Most of the women who hold positions of power and respect around the world, be it in politics, culture, family life, or other aspects of society, are at a point in life where they are not involved in the time-consuming business of physically reproducing. But however common we might think women of a certain age are, there is no getting around the fact that they are virtually unknown in the rest of the animal kingdom. One of the hallmarks of evolutionary theory is that success for a species is measured by offspring. Offspring are how genetic material passes itself through time, and any species that reproduces through combining genetic material is going to have to focus on offspring if it wants to continue. The idea that we deliberately turn off our potential to have children flies in the face of a basic tenet of evolutionary success—that doing well is measured by having children. Yet, even though reproduction is the absolute key to the survival of a species, in humans we give up on reproduction well before the individual itself is done.

It is worth noting that this odd adaptation to living beyond reproduction is really only seen in females. We talk about the oddity of grandmothers but not of grandfathers, because, technically, grandfathers do not outlive their reproductive potential. Despite reduced reproductive success with age, males do not have the same vertiginous shift in hormonal production that females do, and they do not stop producing male gametes (sperm) in the same way that females stop releasing eggs. We know from a vast amount of scientific research on human female fertility that our species really does call time on releasing eggs that can turn into embryos sometime in our fifth decade. Producing those eggs is something that actually happens before we are even born; 7 million potential egg-forming cells (oocytes) in utero become 2 million by the time we are born and are down to about 400,000 before puberty and the hormonal mechanisms even start that would let oocytes become pregnancies. About a thousand oocytes self-destruct each menstrual cycle, but we start with such high numbers that we could in theory keep producing them for 70-odd years after puberty—but we don’t. Something intervenes in our species—and only in biological females—to turn off the entire process. The million-dollar evolutionary question is: why?

Up until this year, only humans and a few whale species had ever been shown to have post-reproductive individuals alive and well in their societies—and all of them female. This has led to a flurry of theorizing about what elements of whale and human evolution might have conspired to create such an extraordinary adaptation as a grandmother. Much of the theoretical background on why these few species, and only these few species, have individuals that happily live on after reproduction is no longer possible has centered on the role those individuals play in promoting group fitness. The aspect of evolutionary biology that has come in for considerable attention in the issue is the role of alloparental care. An alloparent is any animal that does a bit of substitute parenting, be they a biological relative or just another group member. Alloparenting is thought to be evolutionarily advantageous as it allows for a wider support base for group offspring. This support can come in many forms: from providing protection and resources to offering more teachers and playfellows. In social species—like whales and humans—having extra hands is part and parcel of growing up. And for humans, the most well-known explanation of the utterly unlikely existence of grandmothers was first laid out in exactly those terms.

In 1978, researcher Kristen Hawkes and her collaborators proposed “The Grandmother Hypothesis.” Based on Hawkes’s own research with the Hadza people, who are mobile within Tanzania and largely forage food rather than farm, she noted that grandmothers had a very special role in Hadza society because they are expert foragers and carers with years of experience. What’s more, they don’t have children of their own who eat up all those resources. Hawkes’s contribution was to note that in families where grandmothers were around to help their own children provide for their children—particularly their daughters—those grandkids grew better. Even more important from an evolutionary standpoint was that not only did grandmothers enhance the ‘fitness’ of their grandchildren, but their support also meant even more grandkids. Here was a proposal that made sense: the adaptive value that allowed for the evolution of post-reproductive individuals is the contribution of those individuals not only to the next generation but also to the generation after that.

The discovery of post-reproductive whales seemed to add weight to the idea that post-reproductive females are a way to get the benefit of older females without the drain on resources that having children entails. Female orcas, false killer whales, and pilot whales all have been observed to have long periods of life after ceasing reproduction, and all species are highly social, with survival depending on the success of each social unit, thought to be mostly led by females. But in whales, the benefit appears immediately, to the whales’ own children: adult whales with living mothers do better than those without. For both humans and whales, it seems that post-reproductive females are valuable assets who contribute significantly to the survival of their families. This led to two different ways of theorizing the evolutionary role of grandmothers: that they are adaptive because of the contribution of alloparental care (as in humans), or simply because their knowledge and experience make them better resource-gatherers (as in whales).

In 2023, a group of particularly long-lived chimpanzees waded into the debate. In the group of chimpanzees living at Ngogo in Uganda, many of the females survived for quite some time beyond the age of 50, which is the usual point at which chimpanzees stop giving birth. A lack of births in these older individuals combined with hormonal evidence from urine samples that shows the same hormonal changes associated with menopause allowed researchers to suggest that these individuals really are post-reproductive. However, in chimpanzee society, grandmothers do not live in the same group as their daughters and so could not help out the same way Hadza grandmothers do. The adaptive benefit to the chimps is less clear, but the researchers have argued that it is the grandmothers themselves who benefit by not having to compete to reproduce. Their work suggests maybe the reason we haven’t seen grandmother chimps before is that in most chimpanzee groups, life expectancy doesn’t go beyond 50, but at Ngogo, the group has been very successful, with abundant fruit and meat available and most predators (particularly leopards and humans) no longer a threat. This gives us a fascinating insight into the conditions that could have driven our own evolutionary process. Perhaps grandmothers, with their additional resources and valuable experience, are the result of species success—and their success becomes the success of their children, their grandchildren, and their species.

By Brenna R. Hassett

Author Bio:

Brenna R. Hassett, PhD, is a biological anthropologist and archaeologist at the University of Central Lancashire and a scientific associate at the Natural History Museum, London. In addition to researching the effects of changing human lifestyles on the human skeleton and teeth in the past, she writes for a more general audience about evolution and archaeology, including the Times (UK) top 10 science book of 2016 Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death, and her most recent book, Growing Up Human: The Evolution of Childhood. She is also a co-founder of TrowelBlazers, an activist archive celebrating the achievements of women in the “digging” sciences.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Human Bridges, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Socialism’s Self-Criticism And Real Democracy

Richard D. Wolff

Democracy is incompatible with class-divided economic systems. Masters rule in slavery, lords in feudalism, and employers in capitalism. Whatever forms of government (including representative-electoral) coexist with class-divided economic systems, the hard reality is that one class rules the other. The revolutionaries who overthrew other systems to establish capitalism sometimes meant and intended to install a real democracy, but that did not happen. Real democracy—one person, one vote, full participation, and majority rule—would have enabled larger employee classes to rule smaller capitalist classes. Instead, capitalist employers used their economic positions (hiring/firing employees, selling outputs, receiving/distributing profits) to preclude real democracy. What democracy did survive was merely formal. In place of real democracy, capitalists used their wealth and power to secure capitalist class rule. They did that first and foremost inside capitalist enterprises where employers functioned as autocrats unaccountable to the mass of their employees. From that base, employers as a class purchased or otherwise dominated politics via electoral or other systems.

Socialism as a critical movement, before and after the 1917 revolution in Russia, targeted the absence of real democracy in capitalism. Socialism’s remarkable global spread over the last three centuries attests to the wisdom of having stressed that target. Capitalism’s employee class came to harbor deep resentment toward its employer class. Shifting circumstances determined how conscious that resentment became, how explicit its expressions, and how varied its forms.

A certain irony of history made the absence of real democracy in socialist countries an ongoing target of many socialists in those countries. More than a few socialists commented on the shared problem of that absence in both capitalist and socialist countries notwithstanding other differences between them. The question thus arose: why would the otherwise different capitalist and socialist systems of the late 20th and early 21st centuries display quite similar formal democracies (apparatuses of voting) and equally similar absences of real democracy? Socialists developed answers that entailed a significant socialist self-criticism.

Those answers and self-criticism flowed from a recognition that in both capitalist and socialist systems, business enterprises (factories, offices, stores) were organized overwhelmingly around the dichotomy of employer and employee. This was and remains true of private enterprises, whether more or less state-regulated, and likewise of state-owned-and-operated business enterprises. In parallel fashion, much the same was true in slave economic systems: the master-slave organization of productive activities prevailed in both private and state enterprises. Similarly, the lord-serf organization of production prevailed in both state (royal) and private (vassal) feudal enterprises.

Real democracy proved equally incompatible with slave, feudal, capitalist, and socialist systems in so far as the socialist systems retained the prevailing employer-employee structure of their enterprises. In fact, the three kinds of modern socialist systems all display that employer-employee structure. Western European social democracies do so because they leave most production in the hands of private capitalist enterprises that were always built on employer-employee foundations. Moreover, when they established and operated public or state-owned-and-operated enterprises, they copied those employer-employee structures.

Soviet industries—chiefly publicly owned and operated—positioned state officials as employers in relation to employees. Finally, the People’s Republic of China comprises a hybrid form of socialism combining a mix of both of the other forms, a roughly equal split of private and state enterprises. China’s hybrid socialism shares the employer/employee organizational structure in both its state and private enterprises. All three kinds of socialism—social democratic, Soviet, and Chinese—broke in many important ways from the capitalism that preceded them. But they did not break from the basic employer-employee organization of enterprises, that relationship which Marx’s Capital pinpoints as the source of exploitation, that appropriation by employers of the surplus produced by employees.

All three kinds of modern socialism remain crucially incomplete in terms of having not yet gone beyond the employer-employee organization of production. It follows that socialists’ self-criticism—that actually existing socialist systems fell short of their standard of real democracy—may be linked crucially to those systems’ retention of the employer-employee relationship at their economic core.

Employers and employees are, together, defined by a specific class structure. They are its poles, the two possible positions individuals hold in production. They emerged with capitalism out of the disintegrations of previous systems. Such prior systems included (1) feudalism and its economic structure’s two positions of lord and serf, and (2) slavery and its economic structure’s two positions of master and slave. Because masters, lords, and employers are usually few relative to the numbers of slaves, serfs, and employees, and because they live off the surplus extracted from those slaves, serfs, and employees, they cannot allow a real democracy as it would directly threaten their class positions and privileges. In actually existing socialist societies, real democracy’s incompatibility with class-divided economic systems is encountered yet again.

Because this time it is many socialists who make the encounter, they ask why modern socialism, a social movement critical of capitalism’s lack of real democracy, would itself merit a parallel criticism. Why have socialist experiments to date produced a self-criticism focused on their inability to create and maintain authentic democratic systems??

The answer lies in the employer-employee relationship. It always was the key obstacle to real democracy, the cause and literally the definition of those classes whose oppositional existence precludes real democracy. Those socialists who faced the problem of real democracy articulated it as a definition of/demand for “classlessness.” Without classes, no ruling class. If the employees become, collectively, their own employer, the capitalist class opposition disappears. One group or community replaces two. Absent a class-divided economic system, efforts to bring real democracy to a society’s economy and politics could anticipate success.

Socialist self-criticism can enable a solution to real democracy’s absence by advocating for a transition from an employer/employee-based economic system to one based on workers’ self-directed enterprises (or “worker coops” in common language). The incomplete socialisms constructed in the 20th century need to be upgraded by making that transition. That would get those socialisms nearer to completion, nearer to real democracy, and further from capitalist systems whose undying commitment to the employer-employee relationship precludes them from ever getting closer to real democracy.

By Richard D. Wolff

Author Bio:

Richard D. Wolff is professor of economics emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a visiting professor in the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University, in New York. Wolff’s weekly show, “Economic Update,” is syndicated by more than 100 radio stations and goes to 55 million TV receivers via Free Speech TV. His three recent books with Democracy at Work are The Sickness Is the System: When Capitalism Fails to Save Us From Pandemics or Itself, Understanding Socialism, and Understanding Marxism, the latter of which is now available in a newly released 2021 hardcover edition with a new introduction by the author.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

ExxonMobil Wants To Start A War In South America

Vijay Prashad

On December 3, 2023, a large number of registered voters in Venezuela voted in a referendum over the Essequibo region that is disputed with neighboring Guyana. Nearly all those who voted answered yes to the five questions. These questions asked the Venezuelan people to affirm the sovereignty of their country over Essequibo. “Today,” said Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, “there are no winners or losers.” The only winner, he said, is Venezuela’s sovereignty. The principal loser, Maduro said, is ExxonMobil.

In 2022, ExxonMobil made a profit of $55.7 billion, making it one of the world’s richest and most powerful oil companies. Companies such as ExxonMobil, exercise an inordinate power over the world economy and over countries that have oil reserves. It has tentacles across the world, from Malaysia to Argentina. In his Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power (2012), Steve Coll describes how the company is a “corporate state within the American state.” Leaders of ExxonMobil have always had an intimate relationship with the U.S. government: Lee “Iron Ass” Raymond (Chief Executive Officer from 1993 to 2005) was a close personal friend of U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney and helped shape the U.S. government policy on climate change; Rex Tillerson (Raymond’s successor in 2006) left the company in 2017 to become the U.S. Secretary of State under President Donald Trump. Coll describes how ExxonMobil uses U.S. state power to find more and more oil reserves and to ensure that ExxonMobil becomes the beneficiary of those finds.

Walking through the various polling centers in Caracas on the day of the election, it was clear that the people who voted knew exactly what they were voting for: not so much against the people of Guyana, a country with a population of just over 800,000, but they were voting for Venezuelan sovereignty against companies such as ExxonMobil. The atmosphere in this vote—although sometimes inflected with Venezuelan patriotism—was more about the desire to remove the influence of multinational corporations and to allow the peoples of South America to solve their disputes and divide their riches among themselves.

When Venezuela Ejected ExxonMobil

When Hugo Chávez won the election to the presidency of Venezuela in 1998, he said almost immediately that the resources of the country—mostly the oil, which finances the country’s social development—must be in the hands of the people and not oil companies such as ExxonMobil. “El petroleo es nuestro” (the oil is ours), was the slogan of the day. From 2006, Chávez’s government began a cycle of nationalizations, with oil at the center (oil had been nationalized in the 1970s, then privatized again two decades later). Most multinational oil companies accepted the new laws for the regulation of the oil industry, but two refused: ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil. Both companies demanded tens of billions of dollars in compensation, although the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) found in 2014 that Venezuela only needed to pay ExxonMobile $1.6 billion.

Rex Tillerson was furious, according to people who worked at ExxonMobil at that time. In 2017, the Washington Post ran a story that captured Tillerson’s sentiment: “Rex Tillerson got burned in Venezuela. Then he got revenge.” ExxonMobil signed a deal with Guyana to explore for off-shore oil in 1999 but did not start to explore the coastline till March 2015—after the negative verdict came in from the ICSID. ExxonMobil used the full force of a U.S. maximum pressure campaign against Venezuela both to cement its projects in the disputed territory and to undermine Venezuela’s claim to the Essequibo region. This was Tillerson’s revenge.

ExxonMobil’s Bad Deal for Guyana

In 2015, ExxonMobil announced that it had found 295 feet of “high-quality oil-bearing sandstone reservoirs”; this is one of the largest oil finds in recent years. The giant oil company began regular consultation with the Guyanese government, including pledges to finance any and every upfront cost for the oil exploration. When the Production Sharing Agreement between Guyana’s government and ExxonMobil was leaked, it revealed how poorly Guyana fared in the negotiations. ExxonMobil was given 75 percent of the oil revenue toward cost recovery, with the rest shared 50-50 with Guyana; the oil company, in turn, is exempt from any taxes. Article 32 (“Stability of Agreement”) says that the government “shall not amend, modify, rescind, terminate, declare invalid or unenforceable, require renegotiation of, compel replacement or substitution, or otherwise seek to avoid, alter, or limit this Agreement” without the consent of ExxonMobil. This agreement traps all future Guyanese governments in a very poor deal.

Even worse for Guyana is that the deal is made in waters disputed with Venezuela since the 19th century. Mendacity by the British and then the United States created the conditions for a border dispute in the region that had limited problems before the discovery of oil. During the 2000s, Guyana had close fraternal ties with the government of Venezuela. In 2009, under the PetroCaribe scheme, Guyana bought cut-price oil from Venezuela in exchange for rice, a boon for Guyana’s rice industry. The oil-for-rice scheme ended in November 2015, partly due to lower global oil prices. It was clear to observers in both Georgetown and Caracas that the scheme suffered from the rising tensions between the countries over the disputed Essequibo region.

ExxonMobil’s Divide and Rule

The December 3 referendum in Venezuela and the “circles of unity” protest in Guyana suggest a hardening of the stance of both countries. Meanwhile, at the sidelines of the COP-28 meeting, Guyana’s President Irfaan Ali met with Cuba’s President Miguel Díaz-Canel and the Prime Minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines Ralph Gonsalves to talk about the situation. Ali urged Díaz-Canel to urge Venezuela to maintain a “zone of peace.”

War does not seem to be on the horizon. The United States has withdrawn part of its blockade on Venezuela’s oil industry, allowing Chevron to restart several oil projects in the Orinoco Belt and in Lake Maracaibo. Washington does not have the appetite to deepen its conflict with Venezuela. But ExxonMobil does. Neither the Venezuelan nor the Guyanese people will benefit from ExxonMobil’s political intervention in the region. That is why so many Venezuelans who came to cast their vote on December 3 saw this less as a conflict between Venezuela and Guyana and more as a conflict between ExxonMobil and the people of these two South American countries.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

By Vijay Prashad

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

Source: Globetrotter

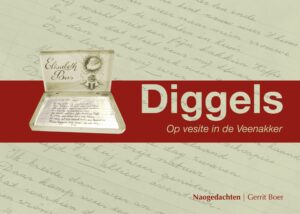

Gerrit Boer – Diggels. Op vesite in de Veenakker. Naogedachten.

Gisteravond was ik al lezend een paar uur in de Altingerhof in Beilen. Op de afdeling voor dementerenden, de Veenakker, woonde de opoe van Gerrit Boer.

Gisteravond was ik al lezend een paar uur in de Altingerhof in Beilen. Op de afdeling voor dementerenden, de Veenakker, woonde de opoe van Gerrit Boer.

Boer heeft met ‘Diggels. Op vesite in de Veenakker. Naogedachten’ een ontroerend boek geschreven over de bezoeken aan zijn oma in de voorbije jaren.

‘Diggels bint weergaves van woorden en bielden die mij bijbleven bint nao jaorenlange vesites in de Veenakker, verpleeghuus in Beilen veur mèensen met dementie. Vesite betiekent: theedrinken en meelkoekjes eten met de woongroep van opoe, kuiern met zien beiden.

Diggels bint naogedachten over een leven in Midden-Drenthe, vertellings over’t dörp, verhalen over de ruilverkaveling, over de moestuun, over törf, over bloempies, over vögels, over ‘t Olde Diepie, over stienen en over dingen die west bint. Zaken die eigenlijk al vergeten bint en toch iniens weer opduukt.

Totdat alles vort is.

Herinnering is seins een singeliere kostganger.’

Het is verleidelijk om aan de hand van citaten te laten zien hoe langzaam, maar onomkeerbaar, opoe verdwaalt in haar eigen wereld. En hoe mooi het Drents is.

Eentje dan:

‘s Aovends nao ’t melken was ’t eten en koffiedrinken. Miesttied las Harm de Asserkraante en ik dee ok wat. Breien, of ik schreef wat op’n bladtie pepier. Op de achterkaante van een kelenderblad of zukswat.

Seins zungen wij ook wal. Harm speulde mondharpie en ik zung. Daar bij die molen of Achter in het stille klooster …

Dat is wal droevig, dat liedtie, moar wij kunden wal mooi zingen met zien beidend.

Het boek is meer dan ‘wal mooi’.

Wat een bijzonder boek.

Gerrit Boer – Diggels. Op vesite in de Veenakker. Naogedachten.

Uitgegeven door Stichting Het Drentse Boek.

ISBN 978 90 6509 272 4

Bestel het boek in de boekhandel of rechtstreek: https://huusvandetaol.nl/…/diggels-op-vesite-in-de…/

We Can Have Either Billionaires Or Democracy. Not Both.

Sonali Kolhatkar

The only way to steer American democracy to safety is to wrest money out of the claws of the wealthiest elites, who now control finances rivaling the economies of whole nations.

As we count down toward the 2024 general election, we should expect to hear from media pundits about candidates and their viability, swing states and the electoral college, likely voters and poll results, and much more. Occasionally we may hear about some issues of importance. Most likely, we will hear little about the urgent need for wealth redistribution in the United States. Extreme inequality remains an invisible scourge underlying so much of what ails society and, even when discussed, is touted as an unavoidable and inevitable outcome of our economy.

However, there is abundant evidence that wealth inequality is the product of intentional design and the idea that what is good for billionaires is good for society. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The Switzerland-based global bank UBS just released its 2023 Billionaire Ambitions report and concluded, “For the first time in nine editions of the report, billionaires have accumulated more wealth through inheritance than entrepreneurship.” Benjamin Cavalli, Head of Strategic Clients at UBS Global Wealth Management said, “This is a theme we expect to see more of over the next 20 years, as more than 1,000 billionaires pass an estimated [$5.2 trillion] to their children.”

That’s more than the economy of the entire United Kingdom. It’s more than the economies of Canada and Mexico combined.

The UBS report was not a critical one and hardly blinked an eye about the obscenity of wealth being hoarded in dynasties. About half of all billionaires around the world use UBS’s banking services, so the bank merely analyzed the investment habits of its most important clients. It did so candidly, referring to “the great wealth transfer” from one generation to the next, avoiding mention of the wealth transfer from the majority of the public to an elite minority.

The report also declared with pride that intent on “continuing the current family legacy, 60% of heirs want to enable future generations to benefit from their wealth.” Of course, they meant future generations of their own families, not in general.

But this wealth transfer is directly the result of tax codes written to benefit the uber-rich. ProPublica’s 2021 analysis of the tax returns of the richest Americans found that they paid an average of 3.4% in taxes, employing armies of lawyers to exploit every loophole carved out to offer special advantages to wealthy elites. Meanwhile, middle-class and working-class Americans pay double-digit tax rates. What this amounts to is collective theft from government revenues.

It’s time to reverse this trend by resorting to a concerted project of wealth redistribution. It’s time to wrest billions, if not trillions, out of the hands of billionaires and their heirs and pour it back where it belongs: to the rest of us.

Call it socialism—which is what the pro-rich rightwing GOP does—or call it progressive taxation, or economic justice. It doesn’t matter; the nation’s fiscal conservatives will demonize any ideas of wealth redistribution and will attempt to instill baseless fears of creeping communism, no matter what specific language we use around fairness. So, we might as well start spelling it out instead of trying to appease the right. After all, there’s a reason why conservatives and wealthy elites want the public to be afraid of socialism: they’re terrified that Americans might be thrilled to embrace policies such as wealth redistribution through taxation.

And if we need any more reasons to put a bullseye on billionaire wealth, it turns out they are vicious, dangerous fascists, whose children are an even more callous lot than their parents.

Billionaires don’t need the protections that democracy offers: earned benefits like Social Security or Medicare, access to free or affordable health care including abortion, labor and wage protections, and due process (they can buy the best legal help when they get in trouble).

In fact, democracy is a threat to their wealth hoarding, which is why they are backing the most dangerous demagogue to have ever occupied the White House: Donald Trump. Economic analyst and former U.S. Labor Secretary Robert Reich lists the numerous billionaires backing Trump for a second term and cites Trump’s promise to wealthy elites, that he plans to “root out the communists, Marxists, fascists and the radical-left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.” Wealthy elites helped bring us Trump’s first term, and they’re itching for a second.

Why wouldn’t billionaires back fascism? It benefits them in ways democracy doesn’t. Indeed, billionaires exist as a design flaw in democracy. The greater the number of billionaires and the greater the wealth they hoard, the weaker the democracy that binds them.

Legislation like Senator Ron Wyden’s Billionaire Income Tax is what they fear if democracy trumps fascism. Wyden’s bill is so modest that it doesn’t target wealth, only income, and would affect fewer than 1,000 Americans, trimming off tiny slivers of their unprecedented hoardings, leaving them as fabulously wealthy as before. After all, is there a real difference between being worth $10 billion versus $9.9 billion?

As to the children of billionaires being worse than their parents, there is a small mention in the UBS report of how heirs of billionaires are far less philanthropic than first-generation billionaires: “while more than [two-thirds] (68%) of first-generation billionaires stated that following their philanthropic goals and making an impact on the world was a main objective of their legacy, less than a third (32%) of the inheriting generations did so.” One could conclude that empathy among children of the ultra-wealthy drops by half each generation. This could be a generation even more determined to fund and fuel fascism in order to protect their riches compared to their parents.

The wealthy are so secure in the protections they have from democratic curbs on their financial power that their biggest worries, as per the UBS report, include “geopolitical tensions,” inflation, recession, and higher interest rates. Fears around a “tight jobs market” and “stricter sustainability rules,” fall low on their list. In other words, they feel secure against threats of wage rebellions and government regulations.

And so, as we hurtle toward authoritarian aristocracy, we must normalize the idea of wealth redistribution. There is no good reason against it, not a single one. We can have either billionaires or democracy, not both.

By Sonali Kolhatkar

Author Bio:

Sonali Kolhatkar is an award-winning multimedia journalist. She is the founder, host, and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a weekly television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. Her most recent book is Rising Up: The Power of Narrative in Pursuing Racial Justice (City Lights Books, 2023). She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and the racial justice and civil liberties editor at Yes! Magazine. She serves as the co-director of the nonprofit solidarity organization the Afghan Women’s Missionand is a co-author of Bleeding Afghanistan. She also sits on the board of directors of Justice Action Center, an immigrant rights organization.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

The Cradle Of Humanity

Grotte de Lascaux – Ills.: en.wikipedia.org

What reading Georges Bataille could teach you about the birth of art—and of humanity.

Why should we explore caves and excavate fossils? Why should we seek more information about our origins? And what can the first women and men tell us about the human condition? Reading Georges Bataille (1897-1962) answers these questions profoundly. The French writer considerably influenced authors such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan, and Julia Kristeva, with provocative novels and essays exploring love, grief, economic theories, social structures, and systems of beliefs. He was also fascinated by prehistoric art and culture, a topic he wrote about in many essays, reviews, and books, including his 1955 book Prehistoric Painting: Lascaux or the Birth of Art. Recent discoveries in paleontology, ethnoarchaeology, and anthropology confirm how relevant some of his ideas about our Neolithic ancestors were.

Bataille’s writings on the topic resulted from much research and by following a scientific methodology. He studied the discoveries of Henri Breuil, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and other specialists in the 1940s and 1950s when social sciences flourished. Like his peers, he was very cautious toward a topic that, he understood, we can only partly apprehend. We lack most references to scientifically analyze what we are excavating, so prehistory remains, in many ways, an “abyss.” He also knew how difficult it is to surpass our cultural perceptions and projections. In “A Meeting in Lascaux,” a 1953 essay in the posthumously published collection of Bataille’s works The Cradle of Humanity: Prehistoric Art and Culture, Bataille writes:

“After more than ten years, we are still far from having fully recognized the magnitude of the discovery of Lascaux… They are within the provinces of both science and desire. Would it be possible to discuss them the way Proust discussed Vermeer or Breton discussed Marcel Duchamp? Not only is it inappropriate to fall under their spell when near them, in the disorder of a visit, lacking the time to collect ourselves, but prehistorians also bid us to keep in mind what these apparitions meant to the men who animated them and who, unintentionally, bestowed them on us.”

Bataille’s approach to prehistory also comes from a very personal, almost intimate experience. He got permission to visit the Lascaux caves in southwestern France alone and would stay there indefinitely, amazed by the prehistoric wall paintings he saw.

The discovery of Lascaux is now part of its legend: on September 12, 1940, 18-year-old Marcel Ravidat and a few other teenagers were the first known to have ventured into the labyrinthine tunnels, pits, and caverns of Lascaux after rediscovering a cave entrance. Their lamp illuminated depictions of thousands of figures, including some heretofore unknown species of animals, humans, and mysterious abstract figures that were, until the discovery of the Lascaux paintings, not known to have even existed.

Bataille marvels at the moment of Lascaux’s rediscovery, connecting the young human witnesses in 1940 to the art made circa 15,000 B.C. He also exclaims about the significance of prehistoric humanity’s divergence from nonhuman animals through the means of art-making, while still being subject to compete against nonhuman animals for survival: “What we now conceive clearly is that the coming of humanity into the world was a drama,” he writes in “The Cradle of Humanity: The Vézère Valley,” the eponymous 1959 essay in The Cradle of Humanity.

A Changing Understanding of the ‘Pit’ Scene

One scene in particular depicted on the walls of a pit in Lascaux appears to have fascinated and even obsessed Bataille. He brings it up repeatedly throughout the works collected in The Cradle of Humanity. The scene depicts, on its left-hand side, a wiry human, drawn faintly and in straight lines. This man’s penis is erect, and he is wearing a bird mask. He appears to be drawn at an angle, as if he is falling to the ground (“It seems like this man is dead,” writes Bataille), and we imagine that he has been knocked down by the bison that appears on the right-hand side. The bison appears wounded, gutted by a spear. Next to the man, a bird hangs on an elongated object—maybe a stick. Further out, in the distance, a rhinoceros is moving away.

This scene, also known as “the pit,” “the well,” or “the shaft,” has been the object of endless interpretation by prehistorians, writers, and philosophers over the last 80 years. Those who have had the chance to observe it in situhave been fascinated by the mysterious protagonists it depicts but have also expressed their discomfort with its violence and sexuality. Who is this man? Has he really wounded the animal? Why does he have an erection? Why is he wearing a bird mask? Does it have anything to do with that other bird on the strange stick, turning his back to this scene?

Georges Bataille – Photo: nl.wikipedia.org

Bataille initially refused to interpret the scene, preferring to express his “heavy indebtedness” to the analyses provided by the prehistorians of his day, such as Henri Breuil, Hans-Georg Bandi, and Johannes Maringer. Though they had different understandings of what was going on there, they shared a “utilitarian” or “functionalist” view that cave paintings were created to “facilitate the work of the hunt,” as Stuart Kendall, one of the translators of Bataille’s work, puts it in his editor’s introduction to The Cradle of Humanity: “Prehistoric hunters attempted to provoke the actual appearance of their prey by painting apparitions of the animals on the cave walls. Painted arrows wounded the icons in anticipation of the actual hunt.” Bataille added some observations made by Claude Lévi-Strauss and other anthropologists to this view while studying tribes of hunters in various parts of the world. “Expiation for the murder of animals killed in the hunt is a rule for many tribes of hunters,” Bataille writes in his 1957 book Erotism. “The act of killing invested the killer, hunter, or warrior with a sacramental character. In order to take their place once more in profane society, they had to be cleansed and purified, and this was the object of expiatory rituals.” So, the scene taking place is one of murder and expiation for Bataille. The bird-man chimera is a “shaman… expiating, through his own death, the murder of the bison,” Bataille writes in Erotism. His bird face is a mask, which forms part of this ritual.

Recent discoveries by archaeological researchers and chemists have analyzed the principal pigments in the Lascaux caves. This scientific progress partly discredits how we have understood the pit scene. The rhinoceros, for instance, is made from a different formula than the one used for the other protagonists. The rhinoceros might have nothing to do with the possible hunting and ritual expiation going on with the bird-man and the bison. On the other hand, pigments from this formula were discovered on the painting of a horse, which is situated on the opposite wall, and that was not previously interpreted as being part of the pit scene. “All the observers were fooled from the start,” affirms Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, anthropologist and emeritus director of research at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS). “We are looking at this wall with images and consider it a scene. We frame it as if we were in a museum. But what proves these images were created to compose a scene? It’s not because they are juxtaposed that they were meant to be read together.”

The Chauvet Cave and the Lascaux Cave

Prudence should always guide us when we look at these cave paintings and interpret them with our subjective, contemporary gaze. Our analyses of prehistoric discoveries are only relevant until contradicted by a new cave, a new fossil, and a new site being excavated. These discoveries often cause us to reevaluate and sometimes contradict a previously held notion, as scientific progress in all disciplines is made.