Where Do Living Creatures Get Their Sense Of Rhythm?

The science of rhythm across species is a new and growing research field, as yet without agreement on the question of whether the phenomenon of rhythm exists for every species. There is, however, fascinating and suggestive experimental and observational evidence: Parrots can bob their heads to a beat; rats can synchronize head movement to music; the cockatoo Snowball is famous for dancing; the California sea lion Ronan can move to music but does not vocalize; and chimpanzees can beat rhythmically on hollow tree trunks.

The science of rhythm across species is a new and growing research field, as yet without agreement on the question of whether the phenomenon of rhythm exists for every species. There is, however, fascinating and suggestive experimental and observational evidence: Parrots can bob their heads to a beat; rats can synchronize head movement to music; the cockatoo Snowball is famous for dancing; the California sea lion Ronan can move to music but does not vocalize; and chimpanzees can beat rhythmically on hollow tree trunks.

Research on human musicality is also advancing; one study found that fetuses were attuned to the rise and fall in the sound of music and speech (cadence) by the last three months in the womb. Further, their baby cries mimicked the cadence of the mother’s native tongue, lilting upward in French and descending in German.

Animals singing and dancing in time to music may seem perfectly natural to human audiences familiar with Disney and other cartoon characters. In reality, each species varies in its capacity to perceive a beat and coordinate movement with it, a synchronized process called entrainment. The research on entrainment in non-human species in the past decade alone has changed the way scientists think about rhythm across species and how it works.

Yet, a consensus on entrainment is still lacking. Although studies have found that dolphins, bats, and songbirds can learn vocal patterns, some researchers have determined that these species have “no evidence of rhythmic entrainment.” An opposing view holds that there is, “in fact, no convincing case” against beat-matching in animals, and that it could be widespread.

As a non-specialist looking at the emerging evidence, the second view seems more likely.

How Rhythm Works

One of the basic questions in the science of rhythm is whether the brain mechanisms enabling rhythm and entrainment are similar in humans and nonhumans.

The physical mechanism of rhythm and synchrony—matching motion, like tapping a foot or bobbing a head—in non-human species is an open research question. The perception of simple rhythms, patterns, periodicities, and the pattern of beats in a musical piece should all be investigated, a 2021 review of the field recommends.

There are two major competing hypotheses of the brain architecture involved in rhythm: gradual audiomotor evolution and vocal learning, each with experimental data to back it up. Gradual audiomotor evolution focuses on the brain’s neural circuit interaction of hearing and movement and does not link with vocal perception. The vocal learning hypothesis centers on the idea that the brain has a preadaptation for vocal cues that evolves genetically and culturally.

The gradual audiomotor evolution hypothesis holds that rhythmic entrainment, the ability to perceive a beat and coordinate movement with it rhythmically, is a complex phenomenon in the human brain involving hearing and the motor system (movement) in a two-way interaction. Until recently, scientists thought that this is a specifically human ability, but newer research indicates that some non-human primates and other animals have the ability to perceive a beat and match it to movements.

Among animals found to have rhythmic entrainment, there are wide variations in aptitude. Some experimental studies found that Rhesus monkeys, when trained, could tap to match a tempo, but macaques could not.

The empirical data from many different experiments suggest that chimpanzees and humans have similar neural circuits involved in perceiving rhythm patterns and that the neural circuits of macaques are less evolutionarily developed in this ability. Doubters of this conclusion suggest that there is so little data that more research might find that macaques are also musically trainable.

Interestingly, the same study found that macaques could synchronize their arm movements with visual cues, but not with vocal cues. (Picture pairs of macaques facing each other, moving their arms in synchronous rhythm.)

An Alternative Hypothesis: Vocal Learning

Vocal learning is an alternative hypothesis, first proposed in 2006, which instead looks at vocal perception and the neural circuit–how sound is perceived and what it is connected to in the brain. When the original vocal learning hypothesis was proposed, there was as yet no research showing beat perception and synchronization in non-human animals, either in the field or in the laboratory.

Based on more recent experimental data, a 2021 study has updated the vocal learning hypothesis. The revised view holds that vocal learning is a “preadaptation for sporadic beat perception and synchronization” that emerges from the coevolution of genes and culture. In other words, a preexisting neural structure develops the ability of a species to take on a new function, in this case, entrainment. Humans have a specialized sound and motion (auditory-motor) circuitry in their brains which enables more complex vocal learning, this theory proposes. The human brain has existing neural oscillations—electrical activity or brain waves—and these get stimulated by sounds outside the body and add new oscillations—waves of regular movement back and forth—to the existing ones.

The vocal learning proponents suggest that vocal learning capacities exist in a continuum across species, providing many areas for further research in beat perception, synchronization, and cognitive gene and culture coevolution.

So far, there is a lack of research into the coevolution of genes and culture, the 2021 study notes, so vocal learning research into the neural specializations that develop could help move general knowledge of coevolution forward. The study points to one coevolution area as an example, the anatomical changes accompanying lactose tolerance that developed 10,000 years ago in dairying cultures.

What About Human Rhythm?

The importance of music in all human cultures is well documented, but how and why it developed evolutionarily is still being investigated as part of the broader question of rhythm. To take one example, recent research indicates that beat perception is probably not the result of the heartbeat, as initially thought, but requires “specific neural networks.”

Another approach is to look at music culturally, as does a 2023 anthropological study supported by the Leakey Foundation, asking why music is ubiquitous across cultures.

An international team of researchers tested hypotheses of the function of music and singing by studying the hunter-gatherer Mbendjele BaYaka people in the Republic of Congo. For two years, the researchers observed a group of BaYakan women who spontaneously sang as they foraged in the rainforest for tubers and other food, concluding that singing produced community spirit, averted potential conflict, and in the words of the BaYakas, made the forest “happy.”

The team was investigating two hypotheses for the evolution of music: first, that singing developed as a tool to signal solidarity in the group and affirm a “willingness” to work together, and second, that it warned against possible dangers. Additionally, the researchers explored the function of mothers singing to their infants.

The researchers observed 1,704 separate foraging trips, 19 percent of which involved singing. The evidence clearly supported the first hypothesis, that the women sang to affirm cooperation and avoid conflict, especially in groups of less familiar women. There was no indication that the purpose of singing was to deter predatory animals. In fact, the researchers found that the BaYaka sing to “please the forest” so that the forest would provide more food.

Another tantalizing possibility is that “touch triggers singing”; the women were more likely to sing when they were holding an infant. They yodeled loudly or patted the infant’s back rhythmically when the child cried.

The study concludes that “music could have originated to signal coalition, particularly cooperative intent or intention to form coalitions within and between groups,” and it suggests future research on coalition signaling in other societies.

A Work in Progress

Based on this brief look at current research among humans and nonhumans, the answer to the question of whether all species have rhythm is “yes.” How exactly this works, how it evolved, and rhythm’s present role in animal and human communication are research topics in progress. Stay tuned!

By Marjorie Hecht

Author Bio:

Marjorie Hecht is a longtime magazine editor and writer with a specialty in science topics. She is a freelance writer and community activist living on Cape Cod.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Human Bridges, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Carbon Farming: A Sustainable Agriculture Technique That Keeps Soil Healthy And Combats Climate Change

01-10-2024 ~ How one North Dakota farmer saved his farm and livelihood using carbon-friendly farming methods.

01-10-2024 ~ How one North Dakota farmer saved his farm and livelihood using carbon-friendly farming methods.

What if there were a way to safely pull billions of tons of carbon out of the atmosphere to substantially reduce or even eliminate global warming?

What if this approach costs relatively little and could be used around the world?

What if it also put billions of dollars in cash into the hands of countless working Americans and people worldwide?

What if it even slashed fossil fuel consumption and made the world more resilient to climate stress?

Well, it turns out there is a system that can do all that. It’s called carbon farming, and it just might be key to restabilizing the climate. In the process, it can revitalize rural economies while also producing healthier, more nutritious crops. And amazingly, it’s also low-cost, low-tech, and low-risk.

The carbon farmer works with simple inputs: land, seed, compost, moisture, sometimes animals and manure, and sometimes specially selected microorganisms that speed a depleted soil’s return to health.

Carbon farming doesn’t pull land out of production or abuse natural ecosystems. It’s a “down-to-earth” solution to global warming that employs nature’s omnipresent carbon cycle, which constantly shuttles carbon molecules into and out of the atmosphere, soil, fresh water, and ocean. Yet carbon farming is still neither widely known nor widely practiced.

A School of Hard Knocks

In well-worn jeans and a plaid shirt, Gabe Brown looks like the North Dakota farmer-rancher he is. But if you were to assume that Brown practices typical U.S. production agriculture, you would be wrong. Brown has an iron will, a deep religious faith, a tremendous capacity for hard work, and “a calling” to bring hope to struggling farmers and ranchers while providing healthful food to consumers. Unlike most farmers, though, he’s not as concerned with yields per acre or dollars per pound as he is with soil health.

How soil became “top of mind” for Brown—and how he became a rock star of regenerative agriculture—is a tale of good tidings for the climate, the planet, and agriculture in the United States.

Early in his farming career, Brown endured modern-day trials of Job. In 1995, he wasn’t much different from many farmers he knew: a young man with a new family, a struggling farm, and a sizable operating loan to service. That year, a hailstorm wiped out 1,200 acres of his spring wheat the day before he was to start harvesting it. Because hail had been uncommon and mild during the previous 35 years, Brown had no hail insurance and was financially devastated.

The bank stuck with him, though, and loaned him more money—but, once again, the following year, hail destroyed his entire crop. At that point, the bank refused to provide a similar new loan.

Brown had to figure out how to ranch and farm without all the expensive chemical fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and genetically modified (GMO) seeds on which neighboring farmers and ranchers depended, and which he now had no money to purchase.

In those days, no one baled the grass in the roadside ditches into hay for cattle because of the garbage and rocks found there. “It was a pain to do,” Brown recalled. But his ranch was relatively small, and he could no longer afford to buy forage for his cattle. So, he went from neighbor to neighbor and asked if he could put the hay in their ditches.

“They just laughed and said, ‘Sure.’” “I would mow it and rake it and bale it. Then I’d carry those small square bales out of that ditch [and] onto the road. At night, my wife would drive with the kids in the car seats with a flatbed trailer behind, and I’d throw those bales onto that trailer one at a time. They probably averaged about 70 or 75 pounds, and I remember years we did 7,000 of them. … That’s a lot of steps up and down a road ditch.”

The next year, 1997, was extremely dry. Brown and his wife Shelly were just able to scrape enough feed together to keep the cattle, but once again, he had no crop income. “So, you just keep digging a bigger hole because we had land payments to make,” he explained.

The next June, another hailstorm cost Brown 80 percent of his crop.

Those four years, Brown said, “were hell to go through. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody, but in the end, it was the best thing that could have happened because it forced me to change my mindset. … I realized, ‘I have to look at my whole operation… from the eyes of nature and how nature functions.’”

Refocusing on the Synergies of Nature

During the years of hail and drought, Brown had often wondered how the 2,000 acres of unplowed native prairie on his land could grow so much forage naturally every year without synthetic inputs. It always had live roots, was always protected by vegetation that sealed in the moisture, and was extraordinarily rich in species.

To figure this out, Brown went to his local public library. There, he read the journals Thomas Jefferson had kept about agricultural practices on his plantation at Monticello, Virginia, where Jefferson planted turnips and vetches to improve degraded soil. Brown also read the journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who had wintered at native Mandan villages in North Dakota—just north of Brown’s ranch—in the early 19th century. The Mandans planted “the three sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—along with tobacco. They were focusing on the synergies of nature, said Brown. They got a legume, a grass, and the squash plant “all working in harmony to benefit each other.” He took note.

Brown also noticed that when the third hailstorm pounded his crops onto the ground, it armored his thirsty soil, sealing in its moisture against drought. This was important because his ranch has no irrigation and gets only 10 to 12 inches of rainfall a year, plus another 5 inches of moisture from melted snow. (It snows there every month except July.)

Informed by his new knowledge of Mandan agriculture, Brown decided to try planting legumes and grass, cover crops that would thrive synergistically through the residue of the hail-killed crops. He intended to raise feed for his livestock and add organic matter to the soil. Then, not even having money to buy the twine to bale hay, Brown simply let his livestock graze off the cover crops. The livestock got a free meal, and their manure enriched the soil. “That started the act of livestock integration on cropland.”

Carbon-Friendly Agriculture

Through his efforts to survive and keep his farm, Brown gained crucial insights into how ecosystems function and the importance of livestock to maintaining a healthy soil ecosystem. Surmounting the challenges this presented forced him to create a new, “carbon-friendly” agriculture that was as economical, as creative, and unconventional.

At a time when many family farms were succumbing to competition from industrial agriculture, Brown was able to avert bankruptcy by throwing out the prevailing business model. Instead of the soil-depleting, additive-heavy, financially draining agricultural practices he had learned in vocational school, his farming techniques mimic nature, heeding soil biology and integrating profitable enterprises in an agrarian ecosystem in which little is wasted; the byproducts of one operation are cleverly used as the inputs or feedstock of another.

As a result, the more than 130 different products sold by Brown’s Ranch include organic, grass-fed beef and lamb, pastured pork and pigs, poultry, honey, fruit, and heirloom vegetables in season, as well as border collies. “Don’t tell me there’s no money in production agriculture!” he said. “There’s a myriad of opportunities.”

These days, instead of baling grass in ditches at night, Gabe Brown is on the road most of the year to consult and lead regenerative agriculture workshops through the nonprofit Soil Health Academy, where he is a partner. “I really believe that my purpose is to give people hope. … By that, I mean farmers and ranchers and now, more so, consumers. … We’re trying to regenerate everything, including climate.”

What Makes Soil Ecosystems ‘Tick’

To understand what Gabe Brown is up to, one has to understand how soil ecosystems operate: they run on carbon, the same way fuel powers an engine. Carbon-rich organic matter gives rich, fertile soils their dark color and clumpy texture and nourishes soil organisms and plants. Carbon-poor soil is less able to support life, producing lower crop yields, less forage, and less biodiversity. Soil health is like a magic elixir for climate health.

Brown’s new approach to farming was not initially aimed at mitigating climate change. He simply noticed that the cover crops he grew, when his fields otherwise would have been fallow, significantly raised the soil’s water-holding ability and put more live roots into it year-round, as on the native prairie; when those cover crops died, their roots decomposed and increased the soil’s organic matter content, nourishing other plants and soil organisms.

So, the organic matter Brown added to nourish his crops and livestock also had the unsought benefit of boosting the soil’s carbon concentration. (Organic matter is more than 50 percent carbon.) Even in harsh, dry North Dakota—where it’s sometimes -40 degrees Fahrenheit in winter—Brown’s agricultural techniques have captured vast amounts of valuable carbon. And that carbon, removed from the air and packed away in the soil, provides climate benefits.

Sequestering Carbon in the Soil

Brown’s Ranch was the subject of a soil survey operation designed by John M. Norman, an environmental biophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Norman analyzed the carbon and nitrogen in the ranch’s top 4 feet of soil. An early measurement he made in 2017 indicated that those horizons contained an extraordinary amount of carbon per acre (92 tons), but the preliminary estimate was never confirmed, despite some follow-up measurements in 2018 and 2019, due to the project’s premature termination. “The amount of carbon he’s sequestered in this soil is staggering,” Norman told me at the time. Even digging 4 feet below the surface wasn’t deep enough for Norman to record all the extra carbon.

Moreover, he said, “The deeper you bury the carbon, the longer it’s going to be in there.” That’s important for climate stability because if the carbon moves back into the air right away, it hasn’t been purged from the atmosphere for the long term. “[Gabe] built a remarkable soil in a couple of decades. … A wise farmer,” Norman concluded, “can grow soil a lot faster than Mother Nature.”

To further increase his soil’s organic matter, Brown nowadays inoculates his seeds with mycorrhizal fungi, and he plants a diverse mix of cover crops to keep the soil from overheating in the summer as the plants capture carbon from the air. Mycorrhizal fungi form a relationship with the roots of vascular plants and are critically important to the development of soil structure, fertility, and water-holding capacity; they also aid plants in using soil nutrients and resisting disease. By promoting plant growth and health, they help increase soil organic matter. “Nature is more collaborative than competitive,” Brown believes.

‘Mob-Grazing’ Pasture

Ultimately, Brown’s cover crops are incorporated into the soil after frost kill and decomposition or when Brown “mob-grazes” a pasture. That’s when cattle trample much of the forage into the soil, protecting it against wind and water erosion and helping it to insulate the ground from temperature extremes, thereby improving warm-weather water retention.

“The hotter it gets, the less water is available for plant growth,” Brown said. “At 70 degrees, 100 percent of the water is available for plant growth. At 100 degrees, only 15 percent is used for growth, and 85 percent is used for evaporation. At 130 degrees, 100 percent of water evaporates; at 140 degrees, soil bacteria die.”

“[Soil] structure is built by a living system of microorganisms—little animals and the roots of the plants,” Norman said. “They basically make a house for themselves and maintain that structure under a condition that’s high yield for the whole system.”

Conventional Versus Regenerative Agriculture

Conventional farmers are addicted to fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides. They see nature as more competitive than cooperative, so they try to remove or poison anything they see competing with their crops—thereby killing beneficial insects and soil life, including the helpful fungi. In addition, conventional farmers often leave the ground bare in the spring, allowing the soil to erode under rushing snowmelt water and pounding rains that can seal its surface, increasing runoff and decreasing water storage.

By contrast, in Brown’s regenerative agricultural system, plant residues are left on the ground to decompose, and tiny organisms come up to the soil surface. “They increase the infiltration rate by a huge factor,” Norman said. This is important not only for allowing adequate moisture to soak in to carry plants through dry spells but also for farmers and ranchers trying to adapt to climate change.

As the climate gets warmer and the frequency and severity of flooding increases, permeable soil is more important than ever to absorb the heavier rainfall. “Gabe Brown’s soil can take a foot of water in an hour with no runoff,” Norman reported. “That’s unheard of in a conventionally tilled agricultural soil.”

By John J. Berger

Author Bio:

John J. Berger is an environmental science and policy specialist, prize-winning author, and journalist. His latest book is Solving the Climate Crisis: Frontlines Reports from the Race to Save the Earth (Seven Stories Press, 2023). He is a contributor to the Observatory.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This adapted excerpt is from Solving the Climate Crisis: Frontline Reports From the Race to Save the Earth © 2023 by John J. Berger and is licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by permission of Seven Stories Press. It was adapted and produced for the web by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

What Is To Be Done?

Richard D. Wolff

01-10-2024 ~ In 1863, the Russian social critic, Nikolay Chernyshevsky, published a novel entitled “What Is to Be Done?” Its story revolves around a central heroine, Vera Pavlovna, and her four dreams. It brilliantly intertwines her personal life and the social turmoil of Russia’s transition at the time from feudalism to capitalism. Chernyshevsky, a revolutionary imprisoned by the Czarist government, wrote a novel that was nothing less than a pioneering work of socialist feminism. In it, he also passionately appealed for an urban, industrial economy based on worker cooperatives, a modern and transformed version of Russia’s earlier agrarian communes. An appreciative Lenin entitled one of his most important political pamphlets, published in 1902, “What Is to Be Done?”

Two decades later, after the Soviet revolution defeated foreign invaders and domestic enemies in a long civil war, Lenin returned to the theme of worker cooperatives. In Soviet circumstances, much changed from Chernyshevsky’s Russia, Lenin argued forcefully for the USSR’s activists to recognize the enormous importance of building, spreading, and respecting cooperatives as key to Soviet socialism’s future. Worker coops, he argued, answered the burning political question among activists then: what is to be done? Here I want to adapt and apply Lenin’s argument to today’s social conditions that are raising that same question even more urgently.

Today’s capitalism is global—the basic economic structure of the world economy features its core employer-employee model. The “relations of production” inside enterprises (factories, offices, and stores) position a small minority of workplace participants as employers. They make all the basic “business decisions” about what, how, and where to produce and what to do with the product (and revenue when they sell it). They alone make all those decisions. Employees, the majority of workplace participants, are excluded from those decisions.

Capitalism today is also globally divided into two major blocs: one old and one new. The old is allied with the United States. Besides being older, the G7 is now the smaller of the two blocs, having shrunk in relative global importance over recent decades. It includes the UK, Germany, France, Italy, Canada, and Japan as well as the United States. The now fast-rising newer bloc, the BRICS, first included Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Recently, it invited six new member states to join, as of January 2024: Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, and Argentina. Since 2020, the BRICS’ total GDP exceeded that of the G7, and that gap between them keeps growing.

The G7’s “mature capitalisms” all survived and grew because workers accepted the employer-employee organization of workplaces. Amid and despite the G7 nations’ endless ideological celebrations of democracy, workers accepted the total absence of democracy inside capitalist enterprises. With some exceptions and resistance, it became routine common sense that representative democracy somehow belonged in residential communities but not in the communities at work. Inside capitalist enterprises, autocracy was the norm. Employers ruled employees but were not democratically accountable to them. Employers in each capitalist enterprise enriched a select circle by delivering portions of the revenue to themselves, to owners of the enterprise, and to a few top executives. That select circle wielded extraordinary political and cultural influence. It replicated the absence of democracy inside its enterprises by keeping the democracy outside them merely formal. Governments in capitalism were typically shaped by that select circle’s paid lobbyists, campaign donations, and paid mass-media productions. In modern capitalism, the kings and queens banished in earlier centuries reappeared, altered, and relocated, as CEOs inside ever larger capitalist enterprises dominating whole societies.

Employees’ actual or anticipated opposition to democracy’s exclusion inside workplaces has always haunted capitalism. One major way employers can deflect such opposition is by narrowly defining their obligation to employees in terms of wages paid to enable consumption. Wages adequate for consumption became the necessary and explicitly sufficient compensatory reward for work. Implicitly, they likewise became the employees’ compensation for the absence of democracy within the workplace. Rising levels of employee consumption signaled a “successful” capitalism. In stark contrast, rising democracy inside the workplace never became a comparable standard for evaluating the system.

Making consumption the point and purpose of work contributed to a social overvaluation of consumption per se. Advertising contributed to that overvaluation too. Modern capitalist society added “consumerism” to its catalog of moral failings. Clerics thus routinely caution us not to lose sight of spiritual values in rushing to consume (of course, those spiritual values rarely include democratic rights inside workplaces).

Confronted and outcompeted by China and the BRICS, G7’s declining empires and economies now risk that mass consumption will increasingly be constrained. In declining empires, the rich and powerful preserve their wealth and privileges while offloading the costs of decline onto the mass of employees. Automating jobs, exporting them to lower-wage regions, importing cheap immigrant labor, and mass campaigns against taxes are the tried-and-true mechanisms to accomplish that offloading.

Such “austerities” are now in full swing nearly everywhere. They explain a good part of the mass working-class anger and bitterness in the older (G7-type) capitalisms expressed in gestures against social “elites.” Given capitalism’s long favoritism shown to its right-wing versus its left-wing critics, it should surprise no one that the anger and bitterness first take right-wing forms (Trump, Boris Johnson, Wilders, Alternative for Germany, and Meloni).

The political temptation for the left will be to focus again as it did in the past on demanding rising consumption now that a declining capitalism undermines it. Capitalism promised a rising consumption that it now fails to deliver. Fair enough, but that is not enough. Often in the past, capitalism was able to deliver rising real wages and workers’ living standards. And it may yet again. Indeed, China is now delivering just that.

The clear lesson is that the left needs a new and different answer to the question of what is to be done. Its criticism must effectively criticize and oppose capitalism when and where it is delivering rising wages and likewise when and where it is not.

Now is the time to expose and attack capitalism’s deprivation of democracy in the workplace and the resulting social ills (inequalities, instabilities, and merely formal political democracy). Workers’ goals never needed to be and should never have been limited to raising wages, important as that was and is. Those goals can and should include a demand for full democracy inside the workplace. Otherwise, whatever reforms and gains workers’ struggles achieve can subsequently be undone (as happened to the New Deal in the United States and social democracy in many other countries). Workers have had to learn that only democratized workplaces can secure the reforms workers win. What is to be done in the old, declining centers of capitalism is for class struggles to include the democratization of enterprises. A transition toward economies grounded on worker-cooperative enterprises is the strategic target.

In the new, ascending capitalisms in the world, the BRICS, a different logic leads again toward worker cooperatives as a focal goal for socialist politics and organizing. Among the BRICS, the same employer-employee model organizes factories, offices, and stores. Unlike the G7, the employers are relatively more often not private. Rather, some employers run privately owned enterprises, while others are state officials who operate enterprises owned by the state. In the People’s Republic of China, where roughly half of enterprises are private and half public, nearly all have adopted the employer-employee organizational model.

Where the state takes a large, major, or commanding role in economic development and especially where one or another socialist ideology accompanies and justifies that role, a turn toward a focus on worker cooperatives is now timely. It will attract many in those countries as socialism’s necessary next step. The “development” or socialism accomplished there—macro-level changes already achieved (via decolonization struggles and revolutions)—are celebrated but also widely understood as insufficient. Bigger social goals and changes motivated those struggles and revolutions. Democratizing enterprises takes “development” to a whole new level reaching toward those goals.

There is yet another source of the answer that now responds to the question: what is to be done? The qualities of democracy that have been achieved within the G7, the BRICS, or most other countries, to date have been more formal than substantive. Where elections of representatives occur, the influences of wealth and income inequalities, the social power wielded by CEOs, and their controls over mass media render democracy more symbolic than real. Many people know it; still more feel it. Extending democracy into the economy and specifically into the internal organization of enterprises represents a major step in moving political democracy beyond merely formal and symbolic to substantive and real. And much the same applies to moving socialism beyond its earlier forms.

The old cry to workers of the world to unify—“You have nothing to lose but your chains”—was an early, partial answer to the question: What is to be done? After a century and a half of development and socialisms, we can now provide a much fuller and more specific answer to that question. To get beyond capitalism’s core—the production relations of employer versus employee—we need explicitly to replace those relations with a democratized workplace, to substitute workers’ self-directed cooperatives for hierarchical capitalist business.

By Richard D. Wolff

Author Bio:

Richard D. Wolff is professor of economics emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a visiting professor in the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University, in New York. Wolff’s weekly show, “Economic Update,” is syndicated by more than 100 radio stations and goes to 55 million TV receivers via Free Speech TV. His three recent books with Democracy at Work are The Sickness Is the System: When Capitalism Fails to Save Us From Pandemics or Itself, Understanding Socialism, and Understanding Marxism, the latter of which is now available in a newly released 2021 hardcover edition with a new introduction by the author.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

The Problem Of Refugee Camps In The Middle East And North Africa

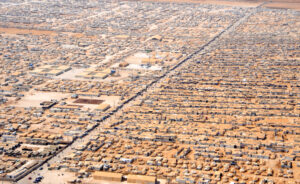

Za’atari refugee camp – Jordan

Photo: en.wikipedia.org

01-08-2024 ~ In 2024, 12 percent of “forcibly displaced and stateless people” are expected to be from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, said the United Nations. This displacement will be caused due to war, humanitarian crises, and environmental catastrophes. The number’s recent causes are the civil war in Sudan and the fallout from natural disasters in Turkey, Syria, Morocco, and Libya. This percentage does not include the millions of people in Palestine who have been displaced since 1948.

At Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan, where 20-year-old pregnant Syrian woman Souad lives, children make up 50 percent of the camp’s population of more than 80,000.

“Raising a child in the camp is difficult. There’s limited access to essential resources such as clothing and baby milk formula,” Souad told the Wilson Center, a U.S.-based policy think tank in June 2023.

For a short while in 2013, Za’atari was the fourth-largest city in Jordan and was host to more than 200,000 people from Syria at the time. The population of the 11-year-old refugee camp has since decreased, but with no sign of an end to the conflict in neighboring Syria, Za’atari remains the biggest refugee camp in the Middle East and one of the largest in the world, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (The vast majority of refugees don’t live in formal camps.)

The UNHCR stated that an estimated 131 million people are projected to be displaced around the world in 2024.

Of the total 131 million people who are projected to be displaced, 63 million are expected to be internally displaced and another 57 million will be refugees or those who are externally displaced, said the UNHCR. As with Za’atari, women and children will make up the vast majority of those who have been displaced.

In 2022, more than three-quarters of the refugees were hosted in low- and middle-income countries, with Turkey leading the way in sheer numbers at 3.6 million followed by Iran at 3.4 million. Meanwhile, “Lebanon hosts the largest number of refugees per capita (one in eight), followed by Jordan (one in fourteen),” stated the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The majority of the refugees in the MENA region are from Syria, where the civil war began in 2011 and continues unabated. More than 5.3 million refugees from Syria are in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and North Africa. Germany also hosts roughly 560,000 Syrian refugees, the most in Europe.

This does not include about 6.8 million internally displaced persons who remain in Syria. About three-quarters of those under the purview of UNHCR in the MENA region were internally displaced, including millions from Yemen’s and Syria’s civil wars.

Za’atari, which features a bustling business thoroughfare known as the Sham Elysees (a play on the Arabic word for Syria and the Parisian avenue Champs-Élysées ), is often highlighted for the “entrepreneurial” spirit of the refugees. But 18-year-old Asia Amari, a resident of the camp, said in 2016 to CNN, “We are not living here, it’s just an existence.”

A visit to another refugee camp for Syrians in Jordan, Azraq, reveals a very different story than the one about a thriving bazaar. Designed as a model camp, Azraq has been characterized as “a heavily controlled, miserable, and half-empty enclosure of symmetrical districts that restricts economic activity, movement, and self-expression.” Refugees have characterized it as an “outdoor prison” and outside observers have called it a “dystopian nightmare.”

Meanwhile, nearly 6 million multigenerational Palestinian refugees fall under the mandate of a different UN body. About 1.5 million Palestinian refugees live in refugee camps in the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, as well as smaller numbers reside in other MENA countries.

According to the United Nations Relief and Work Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), which oversees the camps for Palestinians, “Socioeconomic conditions in the camps are generally poor, with high population density, cramped living conditions, and inadequate basic infrastructure such as roads and sewers.”

For example, the nearly 488,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are stateless and “have very limited access to public health care, education, or the formal economy,” according to the think tank Migration Policy Institute. Nearly 45 percent of them live in camps. According to the nongovernmental organization Anera, “In some Lebanese camps, when the winter rains come, raw sewage washes into people’s homes.” In 2012, a Lancet study published to assess the health and living situation of Palestinian refugees residing in these camps found that 31 percent had chronic medical conditions and 55 percent experienced “psychological distress.” Not only is gender-based violence a major issue in these camps, but according to UNRWA, “[v]iolent clashes [among various groups] are [also] a regular occurrence.”

In another example of the dire conditions of Palestinians, in Gaza, the poverty rate is more than 80 percent, as is the percentage of people dependent on humanitarian assistance. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate was 47 percent as of August 2022. Anera reports that in 2017, 13 percent of the youth population faced malnutrition. And that was before Israel started its genocidal bombing and invasion campaign.

Like many Palestinians, a lot of refugees retain a strong desire to return to their home country, should conditions once more allow for it to be safe for them to go back. But few have the opportunity—for example, in the first eight months of 2023, less than 25,000 Syrian refugees were able to return to the country.

Others, like Amari, wish to resettle in Europe, Canada, or elsewhere. But for now, they are stuck in squalid camps.

By Saurav Sarkar

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Saurav Sarkar is a freelance movement writer, editor, and activist living in Long Island, New York. They have also lived in New York City, New Delhi, London, and Washington, D.C. Follow them on Twitter @sauravthewriter and at sauravsarkar.com.

Source: Globetrotter

Carel C.A. van den Berg – The Making Of The Statute Of The European System Of Central Banks

You can download the complete book (PDF-file) here: CCAvdBerg – MakingofStatute

You can download the complete book (PDF-file) here: CCAvdBerg – MakingofStatute

Dutch University Press, Amsterdam, 2004, 2005 ISBN 90 3169 292 7 – This book is the commercial edition of the dissertation defended and approved at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration of the Vrije Universiteit of Amsterdam on 29 October 2004 . Thesis printed by Thela Thesis – ISBN 90 5170 997 8 (2004).

Zur Thematik

The creation of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) is one of the most profound steps in the monetary history of Europe, which has significance not only for professionals, politicians and academics, but also for everyday life. Among the accomplishments that stand out are the establishment of a federally structured European System of Central Banks (ESCB)[i]and the introduction of a single currency. The opinions and decisions of the European Central Bank (ECB)[ii] are almost daily topics for the national newspapers, discussions on its accountability (or perceived lack thereof) are recurrent topics in the European Parliament and political and academic circles. In short, the ECB has become a reality for almost everyone within a couple of years since its establishment. Technically it has been successful: the transition from national currencies to a single currency, the euro, has been a remarkably smooth process despite the gigantic scale of the operation. Though it is too early to evaluate how effective the ECB is in implementing its mandate, for the Monetary Union as a whole inflation rates are lower than they were during a large part of the nineties.

The legal underpinnings of the System and its independence have been extensively studied, see e.g. Stadler (1996), Smits (1997) and also Endler (1998). Also, from a political angle, the degree in which the negotiations leading up to the signing of the so-called Treaty of Maastricht in February 1992 could be characterized as a success for the German or for the French negotiators has been analyzed, e.g. by Viebig (1999) and Dyson/Featherstone (1999). In many respects these authors have concluded that it was a German success. However, the ESCB is not a copy of an existing central bank, not even the Bundesbank. It has been established on the basis of a unique Statute.[iii] This Statute will guide the ECB, also in the future. But like many texts, the Statute is sometimes ambiguous. For a right interpretation of the texts it is important to know their genesis. Sometimes wording was copied from existing other texts, sometimes texts are a delicate compromise, sometimes texts have a difficult technical history.

What distinguishes this study from these other studies is that these studies analyzed the ESCB from only one perspective, i.e. either from a legal, political or economic point of view. This study aims to show how political, economic and institutional considerations were combined and have found their way into the (legal) wording of the ESCB Statute. To this end I focus on each article, describing the economic rationale behind it as well as its genesis, systematically using historical sources which until now have not been used for these purposes. The perspective I take in order to interpret, analyse and assess the Statute of the ESCB is that of checks and balances. We will identify and study the ‘checks and balances’ which have been introduced in the Statute of the ESCB. ‘Checks and balances’ are an important characteristic of any federally designed system. They are part of the ‘rules of the game’, which have to be taken into account by the components of the system, which rules should ensure the system’s stability and effectiveness. For instance, ‘checks and balances’ prevent the possibility of ‘winner takes all’, because this would mean the end of the federal character. A clear normative framework for checks and balances for federal central bank systems is not available, though there are general notions which any workable system of checks and balances has to accord with. Therefore, we will develop a framework to describe the checks and balances in central bank systems.

The concept of checks and counterchecks also played a role when the American central bank system (the Federal Reserve System, FRS) was designed. A nice description can be found in P.M. Warburg in his book ‘The Federal Reserve System, Its Origins and Growth’ (1930), p. 166: ‘The position of the Reserve Board, as designed in the Act [of 1913], was bound to prove exasperatingly difficult and trying. The office was burdened with the handicap, commonly imposed upon so many branches of administration in a democracy, of a system of checks and counter-checks – a paralyzing system which gives powers with one hand and takes them away with the other. […] Success or failure in such cases generally depends on the wisdom with which the balancing of the checks and counter-checks in a legislative act is handled, and on the intelligence with which, later on, the act is administered.’ And ibidem p. 170: ‘[….] many attempts were made to find a satisfactory answer to the tantalizing puzzle of how to safeguard the autonomy of the reserve banks while giving, at the same time, adequate coordinating and directing powers to the Reserve Board.’ From our study it appears that these considerations were still relevant for the conception of the European central bank.

PVV Blog 2 ~ The Evil French Revolution Has Made Islam Even More Evil

01-08-2024 ~ Liberty, Equality and Fraternity

01-08-2024 ~ Liberty, Equality and Fraternity

Our democracy is indebted to the slogan of the French Revolution ‘Liberty, Equality and Fraternity’, but Party for Freedom leader Geert Wilders rejects the same French revolution.

He even draws a remarkably negative connection between the French Revolution and the world of Islam. What is the common thread behind this connection?

The bloodthirsty history of Islam

In his book Marked for Death. Islam’s War Against the West and Me Wilders describes parts of the history of Islam, based on his view that Islam is an aggressive totalitarian ideology and not a religion. Wilders deals extensively in descriptions of Muslim’ wars of conquest, the genocides they allegedly committed and the slave system they maintained. He also discusses the position of dhimmis, who are usually Jews and Christians, and who have a separate civil status within Islam, with fewer rights than Muslims. Nowhere does Wilders mention a positive aspect of Islam. Islam experienced a period of prosperity and growth from the beginning of its origins in the seventh century but fell into a subordinate position with the rise of Europe as the most powerful continent in the world from around the seventeenth century onwards.

The French Revolution inspires the Muslims

An interesting turning point in Wilders’ description of the alleged violent history and nature of Islam is the following. While in his book he discusses the emerging European supremacy over the world in the seventeenth century and beyond, with Islamic countries falling into the hands of Britain (such as Pakistan), France (Algeria), Italy (Libya), Spain (Spanish Sahara) and the Netherlands (Dutch East Indies), Wilders comes to the following insights: ‘when all seemed lost… Allah saved Islam, orchestrating what in Islamic eyes must look like two miraculous events: the outbreak of the French Revolution and the West’s development of an unquenchable thirst for oil’ (p. 112). Paradoxically, Allah was the driving force behind the French Revolution. In Wilders’ words, this is the same revolution that ‘revamped Islam at a crucial moment when its resourceswere diminishing due to its lack of innovation, the decline of its dhimmi population (i.e., Jews and Christians), and dwindling influxes of new slaves’ (p. 113)’.

Muslims cannot do it alone

Wilders’ reasoning is that Islam in itself stimulates neither development nor creativity. It depends on dhimmis and slaves to live and survive. Now that dhimmis and slaves had been exploited to the bone at the end of the eighteenth century, Islam needed new resources and innovations: the French Revolution provided this. After all, according to Wilders, one of the dogmas of the French revolutionaries was the complete submission of the entire people to the all-powerful state. The French showed the Muslims how they were able to subjugate their own people and virtually all European nations on the continent (at his height, Napoleon controlled large parts of the European continent; JJdR) to the principles of their ideology. It rang a bell and stimulated Muslims to become aware of their glorious past again, or in the words of Wilders: ‘In a sense, Islam encountered a “kindred soul” in Western totalitarian revolutionary thinking’ (p. 113). The line of reasoning is complex. Wilders is convinced of the aggressive character of Islam. Islam had somehow, paradoxically, and against its nature, fallen asleep in the centuries leading up to the French Revolution. God saved Islam by, again paradoxically, allowing the anti religious French Revolution to happen. When the French came to Egypt in 1798, they made the lethargic Muslims remember their glorious past.

Feeling inspired again, they rose to try to restore their once so beautiful empire.

Revolutionary France, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany: it’s a mess

Wilders rejects the French Revolution. In his book he blames Enlightenment thinking for the totalitarian character of the French Revolution. The French Revolution may have given rise to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, the basis of the current Charter of the United Nations, but Wilders still condemns it for its alleged totalitarian character, which culminated in the terror of the guillotine under Robespierre’s reign of terror. He calls Revolutionary France an ‘ideocratic state’ and groups it together with other ‘ideocratic’ states: ‘… such states –whether revolutionary France, the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany – exterminated their perceived enemies with guillotines, gulags and gas chambers’ (p. 32). Not a word in his book about the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or about the principle of human equality, which were also the fruits of this revolution.

Evil encourages evil

The French Revolution was nothing if not evil, and it is this evil that has awakened that other sleeping evil. ‘Islam began from the nineteenth century onward parroting Western

revolutionary jargon, adopting Western technological and scientific innovations, and embracing the belated industrial revolution that Western colonial administration was

bringing to the Islamic world – all with the goal of advancing jihad and world domination’ (p.114). This again sounds like a paradox for a religion that developed independently for the first 1200 years, but apparently that situation had changed. The key question for Wilders is that ‘exposure to Islam is ultimately fatal to us, but for Islam, contact with the West is a vital lifeline. Without the West, Islam cannot survive’ (p. 116). It is a deeply melancholy look at a religion that also produced the Taj Mahal and the Alhambra.

Cut the tires and let them die

Wilders’ view that the West is essential for Islam gives the same West an unexpected dominant position over Islam. If a country wants to get rid of its Muslims, all it has to do is cut ties with the community. The community then dies off automatically. How this should be done is of course a big question, but it will not be a pleasant operation. Cutting ties with Muslims will certainly not become a goal of the new Dutch government under Party for Freedom leadership, currently under construction, the other future coalition parties will not accept that, but it is my belief that it will remain an important ideological driving force in everything the new government will decide: How will measures and legislation in any area, but especially culture and education, ensure that the role of Islam and Muslims in the Netherlands is reduced? The anti-Islam ideology is in the DNA of the Party for Freedom and we will see it surface sooner or later.

Previous posts:

https://rozenbergquarterly.com/pvv-blog-introduction-the-dutch-party-for-freedom-an-analysis-of-geert-wilders-thinking-on-islam/

https://rozenbergquarterly.com/pvv-blog-1-geert-wilders-islam-is-not-a-religion-it-is-a-totalitarian-ideology/