Mirjam de Bruijn ~ ‘The Telephone Has Grown Legs’: Mobile Communication And Social Change In The Margins Of African Society

No Comments yetInaugural Address – September 2008

My phone at home in the Netherlands never stops ringing nowadays and on the display I often see the Malian, Chadian or Cameroonian country codes. And in the evenings there are always ‘missed calls’ from African numbers too. This was unimaginable when I started doing my PhD research in central Mali in the early 1990s. For the people at home then, I was far away. People’s understanding and experiences of distance are very different today.

At breakfast I often speak Fulfulde to Ahmadou, a herder from central Mali who tells me how he is sitting under the trees next to his cows. The costs of communication have apparently dropped so much that he can afford just to call to greet me, the owner of a part of his herd.

We met in 1990 and became like a brother and sister sharing life in the Fulani cattle camp where his father hosted me and my husband. Ahmadou is his eldest son and married two wives and has today 7 children. After the death of his father in 2006, he became the head of his family and clan.

The telephone has given him the chance to change his life, as was apparent when he asked our family to support his political campaign. We agreed; after all it was the least we could do since he had herded our cows for so many years.

Ahmadou has big plans. He would now like to build a house in the city. In one of our phone conversations, he asked me to bring him a television on my next visit. His last call was to communicate his victory in the political campaign!

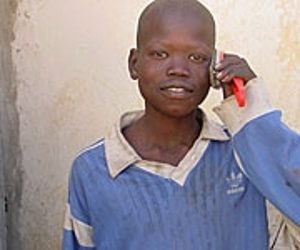

For 35 years, the people of Chad have been living in the midst of a civil war and with repressive state machinery. But even in the regions where war and hunger are a daily reality, people now have access to mobile telephony in spite of widespread deep-rooted poverty. Mongo, the country’s fifth largest

city, has had access to mobile telephony since 2005. I worked and lived in 2002/2003 in Mongo and met with Ousmanou who became one of my research assistants.

Ousmanou did some investigation on his own, being a literate, and together we developed a plan for a NGO (Non-Governmental Organisation) to help impoverished children who live in the streets of Mongo. He is married and has four children. The mobile phone helps to continue our exchanges.

Ousmanou regularly sends text messages to keeps me updated of the recent ups and downs of his family and the city. The telephone has also been a good help to raise some funds for this NGO. However during the last upsurge of fighting in Chad (in 2008, and also before in 2006 and 2007), all telephone connections were cut, which led to a high degree of panic amongst our Chadian acquaintances (and us). With no way of contacting the outside world, their

lives were suddenly once again in the hands of the authoritarian regime of President Idriss Deby.

It will be clear that the way information from these ‘remote’ parts of Africa is being transferred to those in the West has changed with these new methods of communication. The growth of mobile telephony in Africa became possible after the liberalization of the telecommunications market and its

escalation has been astonishing. The unexpectedly high access to mobile telephones has risen from 1 in 50 persons at the beginning of the 21st century to 1 in 3 just a few years later in 2008. Even the inhabitants of remote rural areas in Africa are being introduced to the world of wireless telephony.

Ahmadou and Ousmanou live in marginal regions of the world where modern technology is sparse and where it is not easy to survive due to the difficult natural and economic circumstances of these harsh regions and their political instability. Government interest and investment in marginal regions are usually minimal as they are considered to be areas of little economic or social interest. But Ahmadou and Ousmanou do not see themselves as being marginalized at all. For them, these regions are part of their identity and their use of the mobile phone makes it clear that these marginal areas are not isolated at all, in spite of the absence of good infrastructure. On the contrary, these regions’ relations stretch as far as Europe.The margins cannot be demarcated geographically; they are social margins.

I am interested in the question if and how mobile telephony, a new communication technology, will change the social, political and economic dynamics in the social margins of our world in the coming years? Does it reflect a revolution in communication and development, or will nothing ultimately change at the end of the day?

Ahmadou and Ousmanou and their families in Mali and Chad have become part of these changes. I have been following them and their families since 1990 and 2002 respectively and will continue doing so. And I have recently started a project in the Grassfields area in Cameroon. In the coming years I will be following families in Mali, Chad and Cameroon and try to understand the new dynamics in their societies also through their eyes.

Here, therefore, I am not presenting a completed story but an initial exploration of possible changes in the social margins of Africa. To be able to look into change I will introduce my understanding of the social margins, elaborate on the concept of communication ecology and social relations in the margins. And then I will explore possible social changes that are the result of the new communications technology. I will thus introduce a current and important field of study within African Studies, where interdisciplinary collaboration can make a contribution to the study of mobility and migration, of poverty and of social conflict.

Download Text (PDF): https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/ASC-075287668-2048-01.pdf?

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply