Colonial Film Database ~ Moving Images of the British Empire

Welcome to Colonial Film: Moving Images of the British Empire. This website holds detailed information on over 6000 films showing images of life in the British colonies. Over 150 films are available for viewing online. You can search or browse for films by country, date, topic, or keyword. Over 350 of the most important films in the catalogue are presented with extensive critical notes written by our academic research team.

Welcome to Colonial Film: Moving Images of the British Empire. This website holds detailed information on over 6000 films showing images of life in the British colonies. Over 150 films are available for viewing online. You can search or browse for films by country, date, topic, or keyword. Over 350 of the most important films in the catalogue are presented with extensive critical notes written by our academic research team.

The Colonial Film project united universities (Birkbeck and University College London) and archives (British Film Institute, Imperial War Museum and the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum) to create a new catalogue of films relating to the British Empire. The ambition of this website is to allow both colonizers and colonized to understand better the truths of Empire.

Take a look: http://www.colonialfilm.org.uk/home

Tanja D. Hendriks ~ ‘Home Is Always Home’. (Former) Street Youth In Blantyre, Malawi, And The Fluidity Of Constructing Home

For many Malawians the concept of home is strongly associated with the rural areas and one’s (supposedly rural) place of birth. This ‘grand narrative about home’, though often reiterated, doesn’t necessarily depict lived reality. Malawi’s history of movement and labor migration coupled with contemporary rapid urbanization makes that the amount of people whose lives do not fit this grand narrative, is increasing fast.

For many Malawians the concept of home is strongly associated with the rural areas and one’s (supposedly rural) place of birth. This ‘grand narrative about home’, though often reiterated, doesn’t necessarily depict lived reality. Malawi’s history of movement and labor migration coupled with contemporary rapid urbanization makes that the amount of people whose lives do not fit this grand narrative, is increasing fast.

In the current context of extreme poverty, destitution and devastation – the latter due to the flash floods of January 2015 – slum areas in Blantyre city are growing and so is the number of street children and youth. Some of them are taken in by organizations such as the Samaritan Trust; a street children shelter. This program aims at taking street youth home by ‘reintegrating’ them in their (rural) communities. When asked, the majority of (former) street youth adhere to the grand narrative and state their home to be in a rural village. Yet at the same time, this home is a place they intentionally left and do not wish to (currently) return to. Hence they are generally depicted as ‘homeless’. I wondered: how do (former) street youth in Blantyre, Malawi, engage with ‘the grand narrative about home’ in trying to imagine their ‘becoming at home’ in the city?

My thesis departs from the idea that (the search for) home is an integral part of the human condition. During eight months of ethnographic fieldwork in Blantyre, Malawi, I used qualitative methods – mainly interviews and participant observation – to come to an understanding of the meaning of home for (former) street youth. Some of them, the street girls, currently reside at Samaritan Trust and the former street youth are boys who formerly resided there. Their home-making practices in relation to a marginalized socio-economic position in an overall challenging economic context point towards more fluid and diverse constructions of home that exist alongside the grand narrative without rendering it obsolete. Under pressure, (former) street youth paradoxically attempt to solidify home – even though home remains fluid in practice.

These attempts assist in coping with life in liquid modernity while they are at the same time fraught with contradictions, especially when these solidifications are themselves solidified in policies. These policies subsequently hamper (former) street youth’s becoming at home in town by following the grand narrative and thus confining their homes to rural areas. I conclude that home can best be seen as a fluid field of tensions (re)created in the everyday, thus leaving space for both (former) street youth’s roots and routes. An alternative way in which (former) street youth try to become at home in the city is by searching for a romantic partner to co-construct this (future) home.

This book is based on Tanja D. Hendriks’ Master’s thesis ‘’Home is Always Home’: (Former) Street Youth in Blantyre, Malawi, and the Fluidity of Constructing Home’, winner of the African Studies Centre Leiden’s 2016 Africa Thesis Award. This annual award for Master’s students encourages student research and writing on Africa and promotes the study of African cultures and societies.

Read the book: http://www.ascleiden.nl/home-always-home-former-street-youth-blantyre-malawi-and-fluidity-constructing-home

Stephen Ellis & Gerrie ter Haar ~ Africa’s Religious Resurgence And The Politics Of Good And Evil

Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia, can be found every workday sitting in the dock of a small, bright, ultramodern courtroom in The Hague. Taylor is accused of responsibility for some of the gravest crimes imaginable— atrocities committed in Liberia’s neighbor to the northwest, Sierra Leone, during that country’s 1991–2002 civil war. The crimes include authorizing mass recruitment of child soldiers, mass rape, and hacking off the hands of hundreds of people. Yet Taylor is known as a man who devotes considerable attention to religious matters. His example serves as a reminder that combining the practice of religion with the use of extreme violence is not as unusual as one might think.

The ex-president does not dispute that these crimes actually occurred. Nor does he deny that equally terrible things happened in his own country during the war that was fought there, off and on, between 1989 and 2003. But the charges against him concern Sierra Leone, not Liberia. And he maintains that the atrocities perpetrated in Sierra Leone were none of his doing. It is the first time an African head of state has ever stood trial before an international tribunal. Taylor is appearing before the Special Court for Sierra Leone—a hybrid body created jointly by the state of Sierra Leone and the United Nations. The case is being heard in the Netherlands rather than West Africa for security reasons: Taylor still has a few influential friends in the region.

Most of the time Taylor, born in Liberia in 1948, resembles nothing so much as the benign patriarch of a wealthy family. He wears a dark business suit, a silk tie, and lightly tinted glasses. He has a chunky gold watch on his wrist. He chats affably with his lawyers. Yet not only is he standing trial for war crimes; his eldest son, Charles Taylor Jr., better known as “Chuckie,” currently awaits trial in Florida on charges of torture. Taylor’s speeches, in the days when he was Liberia’s head of state (1997–2003), were full of extravagant references to Jesus. He once declared to a mass rally that Jesus Christ was the true president of Liberia, and he is often described as having been a Baptist preacher. It is also reported that he joined the Nation of Islam during the year when he was held in a Massachusetts jail awaiting extradition to his home country. (Taylor had escaped to America from Liberia in 1983—apparently with $900,000 of government money in his possession—after a dispute with the country’s military dictator. Detained by us authorities at the request of the Liberian government, which wanted to try him for embezzlement, Taylor escaped from the Plymouth House of Correction in 1985.)

Read more: https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/ASC-071342346-186-01.pdf?

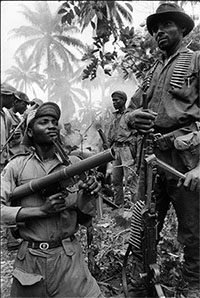

The Nigerian-Biafran War

May 30 2017 marks the 50th birthday of the declaration of independence of the republic of Biafra, leading up to a 30-month civil war between federal Nigerian troops and the (Igbo) secessionists. On the occasion of this anniversary, the Library, Documentation and Information Department at the African Studies Centre in Leiden (ASCL) has compiled a web dossier on the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), also known as the Biafran War.

May 30 2017 marks the 50th birthday of the declaration of independence of the republic of Biafra, leading up to a 30-month civil war between federal Nigerian troops and the (Igbo) secessionists. On the occasion of this anniversary, the Library, Documentation and Information Department at the African Studies Centre in Leiden (ASCL) has compiled a web dossier on the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), also known as the Biafran War.

Far from being an exhaustive or even representative overview of the record of scholarship that has appeared on this topic, this dossier is an attempt to highlight different discourses reflected in the ASCL Library’s collection. After the introduction, section 2 presents a selection of publications on the war, ranging from a 1967 propaganda leaflet by the Nigerian government of information (Unity in Diversity) to a 2016 article on ‘the tensions in Nigeria-Biafra war discourses’. A highlight of this section is a collection of student essays on the civil war written in 1971 at the Toro teacher’s college. The cahiers were donated by their teacher, Aart Rietveld. Noteworthy is also the civil war chapters in the textbook series on civics and history for primary schools.

The third section deals with fictional accounts, personal narratives and poetry on the Biafran conflict, illustrating how much more literature there is than the (rightly famous) writings of Ken Saro-Wiwa, Adichie and Achebe.

Sections 4,5 and 6 capture the conflict through the biographical lenses of key actors. Writings by and about the two political protagonists, General Gowon (Nigerian head of state 1966–1975) and General Ojukwu (president of Biafra 1967–1971), give an insight into the federal and Igbo perspectives of the conflict. The third person chosen for this biographical section is the Yoruba nationalist Obafemi Awolowo, who was active as Federal Commissioner for Finance in Gowon’s cabinet during the war. Chinua Achebe portrays Awolowo as the architect of the starvation policy meant to crush the Igbo defence: “It is my impression that Chief Obafemi Awolowo was driven by an overriding ambition for power, for himself in particular and for the advancement of his Yoruba people in general. […] In the Biafran case it meant hatching up a diabolical policy to reduce the numbers of his enemies significantly through starvation […].”(There was a country, p. 233). This view contrasts strongly with the almost hagiographic accounts of “the man of courage , wisdom, reason and vision” (according to Moses Makinde).

The dossier is concluded with a selection of web resources and is introduced by former LeidenASA fellow Jays Julius-Adeoye, who recently published ‘The Nigeria-Biafra war, popular culture and agitation for sovereignty of Biafra nation’ in the ASCL working paper series.

ASC ~ Education For Life. Akiiki Babyesiza ~ Introduction

On the occasion of the international conference ‘Education for Life in Africa’, organized by the Netherlands Association for Africa Studies in The Hague on 19 and 20 May 2017, the ASCL Library has compiled a web dossier on this theme. The conference is dedicated to Goal 4 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): ‘Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning’.

On the occasion of the international conference ‘Education for Life in Africa’, organized by the Netherlands Association for Africa Studies in The Hague on 19 and 20 May 2017, the ASCL Library has compiled a web dossier on this theme. The conference is dedicated to Goal 4 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): ‘Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning’.

The web dossier contains recent titles from our Library catalogue (from 2013 onwards), divided into six thematic sections. Each title links to the corresponding record in the online catalogue, which provides abstracts and full-text links (when available). The dossier also contains a number of relevant websites. African textbooks present in our Library (for example, on history and on religion), have not been included in this web dossier. They can be searched in our catalogue using the keyword textbooks (form) combined with a keyword such as ‘history’, ‘Islam’ or ‘Christianity’.

The dossier is introduced by Dr Akiiki Babyesiza, an expert in higher education, specializing in Sub-Saharan Africa. Dr Babyesiza has been working for CHE Consult (Berlin), a consulting company in the field of strategic higher education management, since May 2017.

Introduction

Africa is the youngest continent, with half of its population under the age of 15. An inclusive and equitable education sector from pre-primary to higher education that can offer opportunities for this rising young population is at the core of the targets of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning.

In recent decades, the multilateral initiative Education for All and the education related goals of the Millennium Development Goals have led to substantial changes in the field of education in Africa. Yet, the goal of universal primary education has not been achieved and a high proportion of the world’s out-of-school children are African. While access to primary, secondary and higher education has increased, many other challenges persist with respect to equity and quality. Some of the challenges are connected to how and what children learn at school. One important aspect is the language of instruction, which is usually not the pupils’ mother tongue. Often, the lack of educational success is connected to a lack of proficiency in the language of instruction. Another issue is the role of pedagogy and whether students learn to apply knowledge or just to repeat it. This is, of course, also connected to the quality of the education and training of teachers. Moreover, inequities remain between rural and urban areas with respect to the distribution of schools, particularly secondary schools and higher education institutions. And there are inequities with regard to gender, ethnicity, disability and refugee status.

These challenges are exacerbated in situations of war and violent conflict, where educational institutions can worsen as well as mitigate conflict. Students can be marginalized by language, teaching content and the politicization of teaching staff. At the same time, educational institutions that offer peace and civic education for students and accelerated learning programmes for former child soldiers can have a positive impact in post-conflict situations.

Whether in times of war or in times of peace, there is need for a more holistic view of education – from pre-primary education to higher education and technical vocational education and training. The higher education sector, for example, has long suffered from neglect due to the strong focus on primary education in international development debates. Due to the social rates of return theory adopted by the World Bank, higher education institutions in Africa were perceived as an unnecessary luxury. These days, politicians and development actors have embraced the interconnectedness of the different educational sectors. Teachers are taught at higher education institutions, so there cannot be successful primary and secondary schools without quality tertiary education. While the number of higher education students in Sub-Saharan Africa doubled between 2000 and 2010, the rate of youth enrolled in higher education is only around 6% (26% is the global average). Furthermore, many scholars, practitioners and politicians believe that the development of a knowledge economy/society, with higher education institutions at its centre, is key to local and global sustainable development.

Access to education and enrolment: http://www.ascleiden.nl/content/education-life ~ scroll down a little for the web dossier.

Prophecies And Protests ~ Ubuntu And Communalism In African Philosophy And Art

During my efforts to set up dialogues between Western and African philosophies, I have singled out quite a number of subjects on which such dialogues are useful and necessary. Recently I have stated in an essay that three themes in the African way of thought have become especially important for me:

During my efforts to set up dialogues between Western and African philosophies, I have singled out quite a number of subjects on which such dialogues are useful and necessary. Recently I have stated in an essay that three themes in the African way of thought have become especially important for me:

1.1 The basic concept of vital force, differing from the basic concept of being, which is prevalent in Western philosophy;

1.2. The prevailing role of the community, differing from the predominantly individualistic thinking in the West;

1.3. The belief in spirits, differing from the scientific and rationalistic way of thought, which is prevalent in Western philosophy (Kimmerle 2001: 5).

In these fields of philosophical thought there are contributions from African philosophers, which differ in a very characteristic way from Western thinking. Therefore in a dialogue on these themes a special enrichment of Western philosophy is possible. In the following text I want to clarify this possibility by concentrating on two notions, which have a specific meaning in the context of African philosophy. To discuss the notions of ubuntu and communalism means working out some important aspects of the second theme. The community spirit in African theory and practice is philosophically concentrated in notions such as ubuntu and communalism. But the concept of vital force, which is mentioned in the first theme, will play a certain role, too. We find the stem –ntu, which expresses the concept of vital force in many Bantu-languages, also in ubu–ntu. For a more detailed explanation of ubuntu, I will depend mainly on Mogobe B. Ramose’s book, which gives the most comprehensive explanation of the philosophical impact of this notion (Ramose 1999). The concept of communalism is explained in the context of the political philosophy of Leopold S. Senghor and other political leaders of African countries in the struggle for independence (Senghor 1964). A vehement critic of that theory is a Kenyan political scientist, V.G. Simiyu (Simiyu 1987). For a philosophical evaluation of this controversy I will refer to the articles and books of Maurice Tschiamalenga Ntumba, Joseph M. Nyasani, and Kwame Gyekye, dealing with the relation between person and community (Ntumba 1985 and 1988; Nyasani 1989; Gyekye 1989 and 1997).