Being Human: Relationships And You ~ A Social Psychological Analysis – Preface & Contents

Preface

Preface

This book represents a new look at social psychology and relationships for the discerning reader and university student. The title of the book argues forcefully that the very nature of being human is defined by our relationships with others, our lovers, family, and our functional or dysfunctional interactions.

Written in easy to follow logical progression the volume covers all major topical areas of social psychology, with results of empirical research of the most recent years included. A common project between American and European social psychologists the book seeks to build a bridge between research findings in both regions of the world. In doing so the interpretations of the research takes a critical stand toward dysfunction in modern societies, and in particular the consequences of endless war and repression.

Including topics as varied as an overview of the theoretical domains of social psychology and recent research on morality, justice and the law, the book promises a stimulating introduction to contemporary views of what it means to be human.

A major emphasis of the book is the effect of culture in all major topical areas of social psychology including conceptions of the self, attraction, relationships and love, social cognition, attitude formation and behavior, influences of group membership, social influence, persuasion, hostile images, aggression and altruism, and moral behavior.

Table of contents

Introduction

1. The Theoretical Domain and Methods of Social Psychology

2. Cultural and Social Dimensions of the Self

3. Attraction and Relationships: The Journey from Initial Attachments to Romantic Love

4. Social Cognition: How We Think about the Social World

5. Attitude Formation and Behavior

6. The Influences of Group Membership

7. Processes of Social Influence: Conformity, Compliance and Obedience

8. Persuasion

9. Hostile Inter-group Behavior: Prejudice, Stereotypes, and Discrimination

10. Aggression: The Common Thread of Humanity

11. Altruism and Prosocial Behavior

12. Morality: Competition, Justice and Cooperation

References

ISBN 978 90 5170 994 0 – NUR 770 – Rozenberg Publishers – 2008

“Therefore this reading has a rare and valuable feature, that of making a link between American and European social psychology: “Being human: Relationships and you” is an excellent example of how the two lines of thought are actually articulated…it is clearly written, using a professional yet assessable language and therefore easy to read by even the non-specialist public…always pointing to the fact that social psychology is not “just a science” but it deals with issues that constitute the substance of our existence as humans”.

.. auf Lastwagen fortgeschafft. Die jüdischen Bürger in der Stadt Kusel

Aus dem Vorwort: Begleitheft zur Erkundung der Stolpersteine in Kusel: Erinnern Sie sich mit uns an unsere jüdischen Mitbürger in Kusel!

Aus dem Vorwort: Begleitheft zur Erkundung der Stolpersteine in Kusel: Erinnern Sie sich mit uns an unsere jüdischen Mitbürger in Kusel!

Liebe Leserin, lieber Leser,

Jede Stadt hat ihre Geschichte. Das gilt auch für Kusel. Auf das Meiste sind wir stolz. Aber wir scheuen uns nicht, auch dunklere Seiten aufzuzeigen. So stellen wir uns auch dem Schicksal unserer jüdischen Mitbürger und Mitbürgerinnen in Kusel während des Nationalsozialismus. Geschichte prägt Zukunft positiv, wenn man sie gut verarbeitet. Deshalb hat sich die Stadt Kusel mit dem Bündnis gegen Rechtsextremismus Kusel in den Jahren 2006 und 2007 an der Aktion „Stolpersteine“ des Künstlers Gunter Demnig beteiligt, nachdem ein Arbeitskreis sorgfältig die erschütternden Lebenswege der betroffenen jüdischen Familien in Kusel nachgezeichnet hatte. Seit Jahren sind uns die Stolpersteine nun Mahnung, nicht zu vergessen und Auftrag an jeden von uns, sich persönlich in seinem Umfeld immer aktiv für Toleranz, Freiheit und Demokratie einzusetzen. Engagierte Menschen bieten Führungen zu den Stolpersteinen an. Wechselnde Schulgruppen kümmern sich um die Pflege der Bronzeplaketten. Allen Beteiligten sage ich ein herzliches Dankeschön. Für die Idee und die Erstellung des vorliegenden Begleitheftes gilt mein Dank Gerhard Berndt und Hans-Christian von Steinaecker. Das Heft ermöglicht, alle Stolpersteine in Kusel aufzufinden und gibt gleichzeitig Auskunft über das Leben und Schicksal der jüdischen Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, an die sie erinnern.

Ulrike Nagel

Bürgermeisterin der Stadt Kusel

Seite 18: Familie Bermann in der Gartenstraße 8

Gehen Sie zurück Richtung Kreisel und lassen ihn links liegen. Beim nächsten Zebrastreifen wechseln Sie die Fahrbahnseite bis zur nächsten Einmündung, der der Gartenstraße. In diese biegen Sie links ein und erreichen nach wenigen Metern das Anwesen Nr. 8, vor dem Sie auch die 4 Stolpersteine finden.

Karl Bermann (geboren 26.10. 1855 in Konken, gest. „etwa 1930 zu Mannheim“), verh. mit Berta geb. Herz (geboren 26.11.1857 in Ruchheim), lebte in Konken, wo er ein Handelsgeschäft betrieb. Die Eheleute bauten 1905/06 in damals bester Lage der Stadt Kusel das Anwesen Gartenstraße 8 mit Stall und Nebengebäude. Sie zogen 1906 nach Kusel. Karl und Berta Bermann hatten fünf Kinder:

Isidor geboren 21.4.1883 in Konken, meldete sich nach dem Militärdienst am 12.11. 1919 in Kusel polizeilich zur Adresse seiner Eltern. Er verzog dann nach Kaiserslautern (gest. 1935). Seine Witwe Betty lebte im November 1938 in Ludwighafen. Zu ihr flüchtete nach dem Pogrom die Schwägerin Mathilde Heymann. Die beiden Töchter Lore und Susi von Isidor und Betty Bermann überlebten den Holocaust in einem Kloster in Frankreich. Ihr Onkel Rudi Bermann traf sich mit ihnen im August 1945 in einer Kirche in Paris.

Mathilde Heymann geborene Bermann, geboren am 6.5.1884 in Konken, meldete sich 1912, aus Trier zuziehend, ebenfalls in das Haus Gartenstraße 8 wo sie, alleinstehend, die Dachgeschosswohnung bewohnte. Nach dem Pogrom floh sie nach Ludwigshafen zu der Witwe ihres Bruders Isidor Borg. Sie wohnten zuletzt in der Prinzegentenstraße 26, als beide am 22.10.1940 in das Lager Gurs verschleppt wurden. 1942 wurde Mathilde Heymann in das Vernichtungslager Auschwitz transportiert, sie ist dort verschollen. Luitpold, geboren 26.4.1891 in Konken wurde als Kriegsteilnehmer in Verdun schwer verwundet und verlor ein Auge. Er wohnte mit seiner Familie ebenfalls im Haus Gartenstraße 8, wo er mit seinem Bruder Ernst das Handelsgeschäft betrieb. Unter dem Druck des Antisemitismus resignierte Luitpold und emigrierte am 18.6. 1937 in die USA zusammen mit seiner Ehefrau Erna geb. Lehmann (geboren 5.4. 1897), mit Sohn Kurt (geboren 17.6.1923) und mit Tochter Ilse (geboren 1.5.1925).

Paula Bermann, verh. van Es, geboren 9.3.1895 in Konken. Paula war mit den deutschen Truppen im ersten Weltkrieg (1914 – 1918)als Krankenschwester in Frankreich, heiratete den Holländer Coenraad van Es und zog am 17.7.1918 nach Amsterdam. Die Eheleute hatten drei Kinder: Hans, Inge und Sonja. Während der Deportation durch die Nazis sieht Paula ihren Mann im KZ Bergen-Belsen sterben. Sie öffnete sich am 21.1.1945 die Pulsadern, da sie nicht durch deutsche Hände sterben wollte. Tochter Inge überlebte im KZ Bergen-Belsen, Tochter Sonja in einem Arbeitslager und Sohn Hans versteckt bei einer christlichen Familie.

Ernst geboren 23.3.1888 in Konken, wohnte nach Kriegsteilnahme auch im Haus Gartenstraße 8, wo er mit dem Bruder Luitpold das gutgehende und angesehene Pferde- und Viehgeschäft betrieb. Ernst Bermann war verheiratet mit Clara geb. Maier (geboren 30.9.1895 in Malsch). Sie hatten miteinander drei Kinder: Gerda (geboren 18.5.21) Rudolf (geboren 10.7.1922) und Hildegard (geboren 6.1.1927). Die Kinder wurden „deutsch-patriotisch“ erzogen. Ernst Bermann war zunächst der Meinung, das deutsche Volk lasse die Nazis nicht gewähren und ihm könne als Weltkriegsteilnehmer ohnehin nichts geschehen. Das war ein tragischer Irrtum. Nach dem Verbot des Besuchs der höheren Töchterschule für Tochter Gerda und des Progymnasiums für Sohn Rudolf 1936 schickten die Eltern die beiden Kinder in eine Handelsschule nach Frankfurt bzw. Sohn Rudolf in eine Bäckerlehre nach Heilbronn. Mit Hilfe eines Schwagers des Bruders Luitpold konnten die Bedingungen für eine Einreise in die USA erfüllt werden, so dass beide am 15.6.1938 in die USA emigrierten. Für die Eltern und die kleine Tochter Hildegard bleiben die Bemühungen um eine Ausreise erfolglos. In der Nacht zum 10. November 1938 wurde Ernst Bermann mit anderen jüdischen Männern für mehrere Wochen in das KZ Dachau verschleppt. Ehefrau Klara flüchtete mit der Tochter Hildegard nach dem Pogrom zu den Verwandten nach Holland. Nach der Besetzung durch deutsche Truppen wurden Ernst, Klara und Hildegard dort verhaftet und in das Lager Westerborg verschleppt. Ein letztes Lebenszeichen ist eine Postkarte im Besitz von Gerda Lautmann, geb. Bermann. Darauf steht: “Meine Lieben, Päckchen erhalten und herzlichen Dank. Schickt keine mehr. Alles Gute und herzliche Grüße, Ernst und Klara“. Die Familie wurde dann von Westerbork in das KZ Sobibor deportiert. Dort sind die Eltern verschollen. Tochter Hildegard wurde am 21. 5. 1943 in Sobibor ermordet. Gerda Lautmann, geb. Bermann, besuchte mit ihrem Mann 1971 für wenige Stunden ihre Geburtsstadt Kusel. Beide leben in New York.

Das komplette Buch: https://stadt.kusel.de/Stolpersteine/pdf

Alle sinngemäßen und wörtlichen Zitate in dieser Schrift sind dem Buch: „…auf Lastwagen fortgeschafft. Die jüdischen Bürger in der Stadt Kusel” entnommen, das als PDF-Datei kostenlos der folgenden Webseite zu entnehmen ist: http://stadt.kusel.de/stadtgeschichte/auf-lastwagen-fortgeschafft/

Paolo Heywood & Maja Spanu ~ We Need To Talk About How We Talk About Fascism

The word “fascism” has recently reemerged as a key piece of political terminology. The headlines immediately after Donald Trump’s election as president of the US read like a disturbing question and answer session.

The word “fascism” has recently reemerged as a key piece of political terminology. The headlines immediately after Donald Trump’s election as president of the US read like a disturbing question and answer session.

“Is Donald Trump a Fascist?” asked Newsweek. The Washington Post had the answer, declaring “Donald Trump is actually a Fascist”, but later sought to quantify things in a bit more detail with “How Fascist is Donald Trump?”. Meanwhile, Salon agreed that “Donald Trump is an actual Fascist”.

That all raises the question: what actually counts as fascism? It’s a question that has its own history, just as Nazism and fascism themselves do. And it’s similarly not without controversy.

Defining what counted as Nazism and fascism in the immediate aftermath of World War II was an urgent task faced by allied administrators and jurists in Germany and Italy. Examining these projects and their effects may help shed some light on how we talk, or perhaps on how we ought to think before talking, about fascism today.

Read more: https://theconversation.com/we-need-to-talk-about-how-we-talk-about-fascism

Hannah Arendt’s Theory of Totalitarianism – Part One

Hannah Arendt wrote The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1949, by which time the world had been confronted with evidence of the Nazi apparatus of terror and destruction. The revelations of the atrocities were met with a high degree of incredulous probing despite a considerable body of evidence and a vast caché of recorded images. The individual capacity for comprehension was overwhelmed, and the nature and extent of these programmes added to the surreal nature of the revelations. In the case of the dedicated death camps of the so-called Aktion Reinhard, comparatively sparse documentation and very low survival rates obscured their significance in the immediate post-war years. The remaining death camps, Majdanek and Auschwitz, were both captured virtually intact. They were thus widely reported, whereas public knowledge of Auschwitz was already widespread in Germany and the Allied countries during the war.[i] In the case of Auschwitz, the evidence was lodged in still largely intact and meticulous archives. Nonetheless it had the effect of throwing into relief the machinery of destruction rather than its anonymous victims, for the extermination system had not only eliminated human biological life but had also systematically expunged cumulative life histories and any trace of prior existence whatsoever, ending with the destruction of almost all traces of the dedicated extermination camps themselves, just prior to the Soviet invasion.

Although Arendt does not view genocide as a condition of totalitarian rule, she does argue that the ‘totalitarian methods of domination’ are uniquely suited to programmes of mass extermination (Arendt 1979: 440). Moreover, unlike previous regimes of terror, totalitarianism does not merely aim to eliminate physical life. Rather, ‘total terror’ is preceded by the abolition of civil and political rights, exclusion from public life, confiscation of property and, finally, the deportation and murder of entire extended families and their surrounding communities. In other words, total terror aims to eliminate the total life-world of the species, leaving few survivors either willing or able to relate their stories. In the case of the Nazi genocide, widespread complicity in Germany and the occupied territories meant that non-Jews were reluctant to share their knowledge or relate their experiences – an ingenious strategy that was seriously challenged only by Germany’s post-war generation coming to maturity during the 1960s. Conversely, many survivors were disinclined to speak out. Often, memories had become repressed for fear that they would not be believed, out of the ‘shame’ of survival, or because of the trauma suffered. Incredulity was thus both a prevalent and understandable human reaction to the attempted total destruction of entire peoples, and in the post-war era the success of this Nazi strategy reinforced a culture of denial that perpetuated the victimisation of the survivors. In The Drowned and the Saved Primo Levi records the prescient words of one of his persecutors in Auschwitz:

However this war may end, we have won the war against you; none of you will be left to bear witness, but even if someone were to survive, the world will not believe him. There will be perhaps suspicions, discussions, research by historians, but there will be no certainties, because we will destroy the evidence together with you. (Levi 1988: 11)

Here was unambiguous proof of the sheer ‘logicality’ of systematic genocide. The silence following the war was therefore quite literal, and the publication of Origins in 1951 could not and did not set out to bridge that chasm in the human imagination. It did, however, establish Arendt as the most authoritative and controversial theorist of the totalitarian. Read more

The History And Context Of Chinese~Western Intercultural Marriage In Modern And Contemporary China (From 1840 To The 21st Century)

Table of Content

Abstract

Chapter One – Introduction

Chapter Two – An Intellectual Journey: The Theoretical Framework

Chapter Three – Mapping the Ethnographic Terrain: The Methodological Framework

Chapter Five – The Process of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage in Contemporary China

Chapter Six – Why do they marry Westerners? Motivations and Resource Exchanging in Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriages

Chapter Seven – Conflicts and Adjustments in Chinese-Western intercultural Marriage: A Cultural Explanation

Chapter Eight – Epilogue

Bibliography

Appendix I: Interview Questions Guide

Appendix II

Abstract

Intimate relationships between two people from different cultures generate a degree of excitement and intrigue within the couple due to that very difference, however this also brings its own challenges. Intercultural marriage adds an extra set of dynamics to relationships. Although the Chinese culture is very different from Western culture, individuals from both nevertheless meet and fall in love with each other. The existence of intercultural marriages and intimacy between Chinese and Westerners is evident and expanding in societies throughout both China and the Western world. This thesis aims to present a true picture of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage (CWIM) with a focus on the Chinese perspective.

By employing a three-dimensional, multi-level theoretical framework based on an integration of theories of migration, sociology and gender and adopting a qualitative research paradigm, the main body of this study combines three theoretical approaches in order to explore CWIM fully using a panoramic view. The first part of the study is conducted from a macro-level perspective. It provides a historical review of intercultural marriage and transnational marital systems in Chinese history from the modern to the contemporary era through a discussion of the different characteristics of CWIM. The context and background of Chinese intercultural marriages in modern and contemporary China are also reviewed and analysed, such as the related regulations, laws, governmental roles, and so on.

The second section is conducted from a middle-level perspective. On the basis of the study’s fieldwork, the demographic characteristics of the respondents are first disclosed, and different patterns are identified as occurring in CWIM. The approaches to and motivations of CWIM are examined, and a framework of CWIM Push-Pull Forces and a model of Resource Exchanging Layers are established to explain how and why Chinese people have married Westerners. The exchanges and Push-Pull force components operating in Chinese-Western intercultural marriages are also discussed.

The third section offers a micro-level examination of the research, and it moves on to discuss the family relations in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage, particularly with the entrance of a member of a different culture into the Chinese familial matrix. This part of the study focuses on cultural conflicts, origins and coping strategies in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage with an emphasis on the experiences of Chinese spouses. Five areas of marital conflicts are revealed and each area is analysed from a cultural perspective. The positive functions of conflicts in CWIMs are then explored. The six coping strategies and their frequencies of usage by Chinese spouses are further examined.

The final chapter will summarise the points examined previously and will unravel the factors underlying CWIM by recapitulating the symbolic significance, social functions and gender hegemony represented in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage. In this way this study will provide more than an anecdotal description of Chinese-Western Intercultural marriage, but will present a profound analysis of the forces underpinning this cross-cultural phenomenon.

Key Words: Chinese-Western Intercultural marriage, History, Cultures, Motivation, Exchange, Marital Choice, Conflicts.

List of Abbreviations

CCP – Chinese Communist Party

CCW – Chinese Civil War

CH – Chinese Husband

CPC – Communist Party of China

CHWW – Chinese husbands & Western wives

CW – Chinese Wife

CWIM – Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage

CWWH – Chinese wives & Western husbands

DIL – Daughter in Law

EU – European Union

FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FS – Foreign Spouses

IC – Intensity of Conflict

KMT – Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party)

LS – Local spouses

MIL – Mother in Law

MM – Marital Migrants

PRC – People’s Republic of China

ROC – Republic of China

TP – Third Parties Records

USSR – Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

VC – Violence of Conflict

CWWH – Marriage of Chinese Wife and Western Husband

CHWW – Marriage of Chinese Husband and Western Wife

WPA – Western Physique Attraction

The History And Context Of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage In Modern And Contemporary China (From 1840 To The 21st Century)

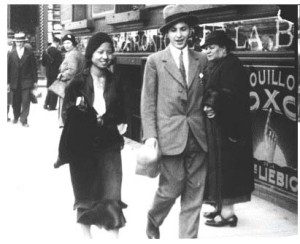

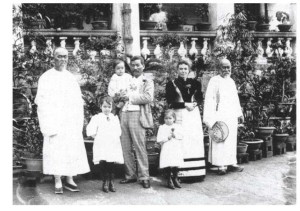

Australian wife Margaret and her Chinese husband Quong Tart and their three eldest children, 1894.

Source: Tart McEvoy papers, Society of Australian Genealogists

1.1 Brief Introduction

It is now becoming more and more common to see Chinese-Western intercultural couples in China and other countries. In the era of the global village, intercultural marriage between different races and nationalities is frequent. It brings happiness, but also sorrow, as there are both understandings and misunderstandings, as well as conflicts and integrations. With the reform of China and the continuous development, and improvement of China’s reputation internationally, many aspects of intercultural marriage have changed from ancient to contemporary times in China. Although marriage is a very private affair for the individuals who participate in it, it also reflects and connects with many complex factors such as economic development, culture differences, political backgrounds and transition of traditions, in both China and the Western world. As a result, an ordinary marriage between a Chinese person and a Westerner is actually an episode in a sociological grand narrative.

This paper reviews the history of Chinese-Western marriage in modern China from 1840 to 1949, and it reveals the history of the earliest Chinese marriages to Westerners at the beginning of China’s opening up. More Chinese men married Western wives at first, while later unions between Chinese wives and Western husbands outnumbered these. Four types of CWIMs in modern China were studied. Both Western and Chinese governments’ policies and attitudes towards Chinese-Western marriages in this period were also studied. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, from 1949 to 1978, for reasons of ideology, China was isolated from Western countries, but it still kept diplomatic relations with Socialist Countries, such as the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries. Consequently, more Chinese citizens married citizens of ex-Soviet and Eastern European Socialist Countries. Chinese people who married foreigners were usually either overseasstudents, or embassy and consulate or foreign trade staff. Since the economic reformation in the 1980s, China broke the blockade of Western countries, and also adjusted its own policies to open the country. Since then, international marriages have been increasing. Finally, this chapter discusses the economic, political and cultural contexts of intercultural marriage between Chinese and Westerners in the contemporary era.

1.2 Chinese-Western Intermarriage in Modern China: 1840–1949

In ancient China, there are three special forms of intercultural/interracial marriages. First, people living in a country subjected to war often married members of the winning side. For instance, in the Western Han Dynasty, Su Wu was detained by Xiongnu for nineteen years, and married and had children with the Xiongnu people. In the meantime, his friend Li Ling also married the daughter of Xiongnu’s King[i]; In the Eastern Han Dynasty, Cai Wenji was captured by Xiongnu and married Zuo Xian Wang and they had two children.[ii] The second example is the He Qin (allied marriage) between royal families in need of certain political or diplomatic relationships. The (He Qin) allied marriage is very typical and representative within the Han and Tang Dynasties. The third example is the intercultural/interracial marriages between residents of border areas and those in big cities. As to the former two ways of intercultural/ interracial marriage in Chinese history, the first one happened much more in relation to the common people plundered by the victorious nation, while the second one was an outer form of political alliance. The direct reason for the political allied marriage was to eliminate foreign invasion and keep peace. In that case, when the second form went smoothly, the first form inevitably ceased, however, when the first form increased, the second form failed due to the war. Read more

- Page 2 of 3

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- next page