Dutch Prize Papers

HCA 32 / 1845.1: A box with ship’s documents, court papers, ship’s journals, cash books and a wallet with a small French prayer book, seized in the 17th century during the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars. Source: Sailing Letters Journal IV, Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2011, 12; picture: Erik van der Doe

The Prize Papers are documents seized by British navy and privateers from enemy ships in the period 1652-1815. These papers are kept in the archive of the High Court of Admiralty in The National Archives in Kew (London). Approximately a quarter of the Prize Papers originates from Dutch ships. Apart from ship’s journals, lists of cargo, accounts, plantation lists and interrogations of crew members, this collection also contains approximately 38,000 business and private letters. The letters originate from all social strata of society and most of them never reached their intended destination.

Research

The huge variety of the Prize Papers makes it suitable for different types of research. It means that the Prize Papers can be used for a wide range of research topics, for example, for developments in language and dialect, trade, material culture, social relationships and knowledge transfer from the 17th to the 19th centuries. A large international research project by the universities of Oxford and Birmingham led by Jelle van Lottum focused on the migration of sailors and the distribution of human capital, based on records of interrogations of crew members. This research was financed by the Economic and Social Research Council (2011-2016).

The Sailing Letters’ project carried out by the National Library of the Netherlands in 2004, introduced the Prize Papers to a broad group of Dutch researchers. Five Sailing Letters Journals were published between 2008 and 2013 to make this rich and versatile resource even more widely known.

Preservation and digitisation

The award at the end of 2015 of a substantial subsidy to Huygens ING by Metamorfoze, the national programme for the preservation of paper heritage, made it possible to preserve and digitise 144.000 pages of selected documents.

Go to: https://www.huygens.knaw.nl/dutch-prize-papers/

or: https://prizepapers.huygens.knaw.nl/

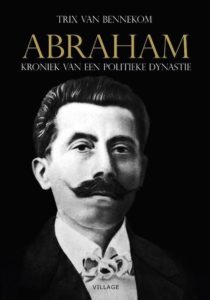

Trix van Bennekom ~ Abraham. Kroniek van een politieke dynastie

Eén van de families die de geschiedenis van Bonaire mee bepaald heeft, is de familie Abraham.

Eén van de families die de geschiedenis van Bonaire mee bepaald heeft, is de familie Abraham.

Trix van Bennekom begint het verhaal in de Heilige Vallei in het noorden van Libanon. Die vallei bood meer dan duizend jaar bescherming aan een vroegchristelijke geloofsgemeenschap, de Maronieten.

Daar, in het dorpje Serhel, werd Julian Antonio Abraham geboren in 1870. Deze Julian maakte in 1895 de stap naar de nieuwe wereld. Hij emigreerde naar Amerika. Maar al snel vertrok hij naar Venezuela, om uiteindelijk zich in 1903 op Curaçao te vestigen.

Binnen de familie Abraham deden diverse verhalen de ronde over hun afkomst. Maar niemand wist van deze achtergrond. Het plezier over de reconstructie straalt van het gezicht van Van Bennekom als ze over deze vondst vertelt. Voor een biograaf is er natuurlijk ook niets mooiers te bedenken. Zo geef je de familie waarover je schrijft haar geschiedenis terug.

Het boek verhaalt over de drie Abrahammen die in de politiek van het eiland een grote rol hebben gespeeld. In de typeringen van Van Bennekom: Julio, de man van het volk, Toon, de zakenman-politicus en Jopie, de revolutionair.

Wat het boek bijzonder maakt, naast de mooi geschreven portretten, is de beschrijving van de tijd waarin de drie politieke carrières zich afspeelden. Van Bennekom verhaalt niet alleen de geschiedenis van het Caribisch gebied, maar ook de verhouding van dat gebied met dat moederland daar in Europa.

De combinatie van de persoonlijke en de grote geschiedenis maakt Abraham een rijk boek.

Uitgeverij Village – Imprint VanDorp uitgevers – ISBN 978 94 61852 120

Imaging Africa: Gorillas, Actors And Characters

Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa.

Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa.

Although there was much negative representation in these films I will discuss how films set in Africa provided opportunities for black American actors to redefine the way that Africans are imaged in international cinema. I conclude this essay with a discussion of the process of revitalisation of South African cinema after apartheid.

The study of post-apartheid cinema requires a revisionist history that brings us back to pre-apartheid periods, as argued by Isabel Balseiro and Ntongela Masilela (2003) in their book’s title, To Change Reels. The reel that needs changing is the one that most of us were using until Masilela’s New African Movement interventions (2000a/b;2003). This historical recovery has nothing to do with Afrocentricism, essentialism or African nationalisms. Rather, it involved the identification of neglected areas of analysis of how blacks themselves engaged, used and subverted film culture as South Africa lurched towards modernity at the turn of the century. Names already familiar to scholars in early South African history not surprisingly recur in this recovery, Solomon T. Plaatje being the most notable.

It is incorrect that ‘modernity denies history, as the contrast with the past – a constantly changing entity – remains a necessary point of reference’ (Outhwaite 2003: 404). Similarly, Masilela’s (2002b: 232) notion that ‘consciousness of precedent has become very nearly the condition and definition of major artistic works’ calls for a reflection on past intellectual movements in South Africa for a democratic modernity after apartheid. He draws on Thelma Gutsche’s (1972) assumption that film practice is one of the quintessential forms of modernity. However, there could be no such thing as a South African cinema under the modernist conditions of apartheid. This is where modernity’s constant pull towards the future comes into play (Outhwaite 2003). Simultaneous with the necessary break from white domination in film production, or a pull towards the future away from the conditions of apartheid, South Africans will need to re-acquire the ‘consciousness of precedent’, of the intellectual and cultural heritage of the New African Movement, such as is done in Come See the Bioscope (1997) which images Plaatjes’s mobile distribution initiative in the teens of the century. The Movement’s intellectual and cultural accomplishments in establishing a national culture in the context of modernity is a necessary point of reference for the African Renaissance to establish a national cinema in the context of the New South Africa (Masilela 2000b). Following Masilela (ibid.: 235), debates and practices that are of relevance within the New African Movement include:

1. the different structures of portrayal of Shaka in history by Thomas Mofolo and Mazisi Kunene across generic forms and in the context of nationalism and modernity;

2. the discussion and dialogue between Solomon T. Plaatje, H.I.E. Dhlomo, R.V. Selope Thema, H. Selby Msimang and Lewis Nkosi about the construction of the idea of the New African, concerning national identity and cultural identity;

3. the lessons facilitated by Charlotte Manye Maxeke and James Kwegyir Aggrey in making possible the connection between the New Negro modernity and New African modernity;

4. the discourse on the relationship between Marxism and modernity within the context of the Trotskyism of Ben Kies and I.B. Tabata and the Stalinism of Michael Harmel, Albert Nzula and Yusuf Mohammed Dadoo; and

5. the feminist political practices of Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi, Phyllis Ntanatala and others.

Read more

Merijn Oudenampsen ~ The Conservative Embrace Of Progressive Values. On The Intellectual Origins Of The Swing To The Right In Dutch Politics

To talk of ideology in the Netherlands is to court controversy. The Dutch are not exceptional in that sense. Ideology is known internationally to have a bad reputation. After all, the word first came into common use when it was employed by Napoleon as a swearword. But the Dutch distaste for ideology seems to have taken on particularly sharp features. The country lacks a prominent tradition of political theory and political ideology research and often perceives itself as having achieved the end of ideology. Taking recourse to Mannheim’s sociology of ideas, I have attempted to contest that image and fill a small part of the lacuna of Dutch ideology studies. The book started out with an attempt to formulate – in broad strokes – an explanation for the peculiarly apolitical atmosphere in Dutch intellectual life.

To talk of ideology in the Netherlands is to court controversy. The Dutch are not exceptional in that sense. Ideology is known internationally to have a bad reputation. After all, the word first came into common use when it was employed by Napoleon as a swearword. But the Dutch distaste for ideology seems to have taken on particularly sharp features. The country lacks a prominent tradition of political theory and political ideology research and often perceives itself as having achieved the end of ideology. Taking recourse to Mannheim’s sociology of ideas, I have attempted to contest that image and fill a small part of the lacuna of Dutch ideology studies. The book started out with an attempt to formulate – in broad strokes – an explanation for the peculiarly apolitical atmosphere in Dutch intellectual life.

The relative absence of ideological thought in the Netherlands, I have argued, can be traced back to the historical dominance of one particular form of ideological thought: an organicist doctrine that considers Dutch society as a differentiated, historically grown, organic whole. It considers the state and the media as the passive reflection of societal developments, with elites serving as conduits. Organicism is a sceptical, relativist ideology that stresses harmony and historical continuity. Shared by the twentieth-century elites of the different currents in the Netherlands, this ideology has been depicted as the metaphorical roof uniting the different pillars. It has filtered through Dutch intellectual history in complex forms, to emerge in more contemporary manifestations such as Lijphart’s pluralist theory of accommodation.

The thesis of this book is that this has resulted in a lingering tendency in the literature to downplay conflict, rupture and ideology in Dutch history. And instead to favour more harmonious portrayals of Dutch society developing gradually and continuously as a unity, as an organic whole. When it comes to the Fortuyn revolt, a similar inclination has resulted in depoliticized interpretations of the revolt as the exclusive imprint of secular trends that Dutch politics and media simply needed to reflect. Hans Daalder, the doyen of Dutch political science, argued that there is a political incentive to depoliticize matters in the Dutch political system. In the context of the close relationship between politics and social science in the Netherlands, this has given rise to a paradoxical reality: the more politically involved social science becomes, the more depoliticized it needs to become. Ironically, this means that a more autonomous social science will need to repoliticize its account of Dutch political transformation to some degree. That is what this study has sought to do.

See: https://pure.uvt.nl/Oudenampsen_Conservative.pdf

Reshaping Remembrance ~ Critical Essays On Afrikaans Places Of Memory

Albert Grundlingh & Siegfried Huigen (Eds.) – Reshaping Remembrance. Critical Essays on Afrikaans Places of Memory – Rozenberg Publishers 2011 – Savusa Series 3 – ISBN 978 90 3610 230 8 – Editing: Sabine Plantevin.

In any society in the throes of transition, there is a particularly acute need to reflect upon aspects of the past that used to represent firm beacons enlighting the way ahead. This inevitably involves a broader re-appraisal of the processes which contributed to the formation of a specific historical memory in the first place.

Reshaping Remembrance includes a number of critical essays on dimensions of collective Afrikaans historical memory in South Africa. In the light of radical changes in the country, scholars from various disciplines reflect on the dynamics of historical consciousness symbolically present in various areas: the ‘volksmoeder’ image, historical events and monuments, language and music, rugby and architecture.

This work hopes to resound with a well-established intellectual tradition in Europe dealing with ‘places of memory’ or ‘lieux de mémoire’.

Contents

1. Siegfried Huigen & Albert Grundlingh – Koos Kombuis and Collective Memory

2. Elsabé Brink – The ‘Volksmoeder’ – A Figurine as Figurehead

3. Gerrit Olivier – The Location

4. Hein Willemse – A Coloured Expert’s Coloured

5. Kees van der Waal – Bantu: From Abantu to Ubuntu

6. Ena Jansen – Thandi, Katrina, Meisie, Maria, ou-Johanna, Christina, ou-Lina,Jane and Cecilia

7. Albert Grundlingh – Rugby

8. Marlene van Niekerk – The Eating Afrikaner: Notes for a Concise Typology

9. Lizette Grobler – The Windpump

10. Hans Fransen – Glorious Gables

11. Lou-Marié Kruger – Memories of Heroines: Bitter Cups and Sourdough

12. Lize van Robbroeck – The Voortrekker in Search of New Horizons

13. Christine Antonissen – English

14. Siegfried Huigen – Language Monuments

15. Rufus Gouws – The Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal

16. Luc Renders – And the Greatest is … N.P.van Wyk Louw

17. Albert Grundlingh – Why have a Ghost as a Leader? The ‘De la Rey’ Phenomenon and the Re-Invention of Memories, 2006-2007

18. Stephanus Muller – Boeremusiek

19. Stephanus Muller – Die Stem

20. Annie Klopper – ‘In ferocious anger I bit the hand that controls’: The Rise of Afrikaans Punk Rock Music

Reshaping Remembrance ~ Koos Kombuis And Collective Memory: An Introduction

As the year 2006 gave way to 2007, a song and an accompanying music video about the Boer general Koos de la Rey caused quite a stir in South Africa. When this song was played in bars and at barbecues, young white Afrikaners would stand with their fists clenched against their chests and sing along: ’De la Rey, De la Rey…’ And tears would flow. According to news reports, the ‘De la Rey thing’ had made many of them ‘proud’ of their roots. Worried ANC politicians expressed concern because they saw this as the start of an ethnic revival that could disrupt South Africa. The phenomenon even made it to the world press.

As the year 2006 gave way to 2007, a song and an accompanying music video about the Boer general Koos de la Rey caused quite a stir in South Africa. When this song was played in bars and at barbecues, young white Afrikaners would stand with their fists clenched against their chests and sing along: ’De la Rey, De la Rey…’ And tears would flow. According to news reports, the ‘De la Rey thing’ had made many of them ‘proud’ of their roots. Worried ANC politicians expressed concern because they saw this as the start of an ethnic revival that could disrupt South Africa. The phenomenon even made it to the world press.

One of the more balanced reactions to the De la Rey song is an article by the Afrikaans beat poet Koos Kombuis on Litnet, ‘Bok van Blerk en die bagasie van veertig jaar’ (Bok van Blerk and the baggage of forty years).[i] In this article Kombuis confesses his conflicting reactions to the song. Rationally, he rejects the song and the Boer War elements in the music video. He sees it as ‘a call to war, a sort of musical closing of the ranks’. Some months before Kombuis had distanced himself publicly from his Afrikaner identity in a Sunday newspaper, from the ‘baggage that has been forced on me by people who have now been trying to prescribe for forty years who and what an Afrikaner is. What an Afrikaner is supposed to believe in. Whom he should vote for, which shit clothes he should wear and how he should spend his public holidays’.[ii] This notwithstanding, Kombuis is unable to offer any resistance to the emotional appeal of the song: ‘Why, if I experienced my resignation from Afrikanerdom as such a gloriously liberating step, do I feel so inexplicably profoundly touched by the De la Rey song? It is embarrassing’.

In reply to Kombuis’s question ‘why’, it can be surmised that both the song and the video, with their images of the leadership, a concentration camp and Boer fighters, draw on the collective memory of white Afrikaners, on something they learned within the family and, especially for the older ones, at school and in church. Kombuis’s reaction already points in this direction when he says that when he hears the song, he longs to be back at Sunday school and ‘feels like rejoining the army on the spot and shooting the hell out of the Kakies and other K stuff’.[iii]

The role of collective memories was first investigated seriously by the French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs in his ground-breaking works Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire (The social frameworks of memory) and La mémoire collective (The collective memory). These publications from 1925 and 1950 were rediscovered in recent years by historians doing research on memory. According to Halbwachs, every one of us obviously has his own memories, but at the same time we also share group memories. Read more