George Orwell – Politics And The English Language

“Politics and the English Language” (1946) is an essay by George Orwell that criticised and ended the “ugly and inaccurate” written English of his time and examines the connection between political orthodoxies and the debasement of language.

The essay focuses on political language, which, according to Orwell, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind”. Orwell believed that the language used was necessarily vague or meaningless because it was intended to hide the truth rather than express it. This unclear prose was a “contagion” which had spread to those who did not intend to hide the truth, and it concealed a writer’s thoughts from himself and others. Orwell encourages concreteness and clarity instead of vagueness, and individuality over political conformity.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Politics_and_the_English_Language

Revolutie in galop – De onmisbare rol van het paard in de Mexicaanse Revolutie

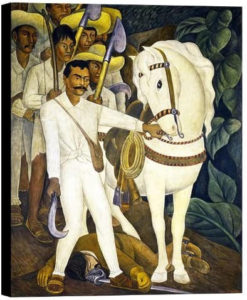

De Mexicaanse kunstenaar Diego Rivera maakte in 1932 een litho van de legendarische Mexicaanse boerenleider Emiliano Zapata (1879-1919). Niet zonder reden beeldde hij deze af staand naast zijn witte paard. Zapata was niet alleen een groot paardenliefhebber, maar Rivera symboliseerde hiermee de rol van het paard in de zapatistische revolutie. Hij realiseerde zich dat Zapata en zijn boerenlegers onmogelijk zonder paarden hun revolutionaire strijd hadden kunnen voeren. Dat gold eveneens voor Zapata’s evenknie tijdens de Mexicaanse Revolutie, Pancho Villa (1877?-1923). De tactische strijdmethodes die door beide legerleiders werden toegepast waren alleen mogelijk dankzij een grootschalige inzet van paarden.

Strijdtoneel

Wie wel eens een speelfilm over de Mexicaanse Revolutie (1910-1920) heeft gezien, kent de beelden: in opstuivend zand stormen legers te paard een stad binnen en mannen met sombrero’s, behangen met kogelgordels, schieten schijnbaar doelloos alle kanten op. In de meeste gevallen geven deze films een nogal geromantiseerd beeld van de revolutie en van de leiders Zapata en Villa.[1] Authentieke filmbeelden van Zapata en Villla uit de revolutie hebben echter wel degelijk de basis gelegd voor de uit Hollywood afkomstige clichébeelden.

Over de Mexicaanse Revolutie zijn honderden boeken geschreven.[2] Daarin wordt uitgebreid aandacht besteed aan de door Zapata en Villa toegepaste guerrillatechnieken.

In tegenstelling tot de Franse Revolutie van 1789 en de revoluties in de negentiende eeuw (1848 en de Commune van Parijs in 1871) die plaatsvonden in een stedelijk decor, was de Mexicaanse Revolutie de eerste grootschalige revolutie waarbij steden niet het strijdtoneel vormden. De revolutie speelde zich af in een diversiteit van landbouw- en veeteeltgebieden, woestijn, plattelandsdorpen en bergen.

Zonder gebruik te maken van het paard als vervoermiddel en strijdmiddel, zou deze revolutie in de ontstane vorm nooit hebben plaatsgevonden. De vanzelfsprekende, onmisbare rol van het paard in het dagelijks leven van de meeste Mexicanen – als vervoermiddel en op boerenbedrijven – ontwikkelde zich bijna vanzelfsprekend naar die van essentieel hulpmiddel in de strijd om een beter bestaan.

Hacendados

Emiliano Zapata, geboren in de zuidelijke Mexicaanse staat Morelos, behoorde niet tot de armste klasse in Mexico. Zijn familie had een klein boerenbedrijf. In Morelos leden de kleine boeren voortdurend onder de misdaden van de grote landeigenaren, de hacendados. Deze eigenden zich land, waterbronnen en soms hele dorpen (pueblos) toe om hun suikerplantages te kunnen uitbreiden. De hacendados voelden zich gesteund door de Mexicaanse dictator Porfirio Díaz, die regeerde van 1876 tot 1911. De kleine landeigenaren en onafhankelijke boeren stonden volgens Díaz de vooruitgang van Mexico in de weg. Zapata wierp zich op als hun vertegenwoordiger en protesteerde voortdurend bij de lokale autoriteiten tegen de handelswijze van de hacendados. Dit had geen enkel resultaat. Zij zagen Zapata als een vervelend obstakel voor hun belangen. Om hem uit de streek weg te krijgen, wist men hem over te halen dienst te nemen in het leger. Daar viel hij op door zijn vakmanschap in de omgang met paarden. Na een half jaar hield hij het leger voor gezien en keerde hij terug naar zijn dorp waar hij als burgemeester werd gekozen. Al voor 1910 begon hij met medestanders stukken land die door de hacendados waren ingepikt, terug te veroveren.

Landhervormingen

In 1911 moest Díaz onder druk van presidentskandidaat Francisco Madero het land verlaten.[3] Madero had plannen tot landhervorming en zocht daarvoor steun bij lokale leiders. In de noordelijke staat Chihuahua vond hij de plaatselijke bandiet Doroteo Arango, beter bekend als Pancho Villa, aan zijn zijde. Zapata steunde weliswaar de plannen van Madero, maar vanwege diens achtergrond als grootgrondbezitter, bleef hij hem wantrouwen.

Eenmaal president, kwam van de landhervormingen van Madero niets terecht. Zapata keerde zich tegen Madero en kwam met een eigen plan voor landhervorming, het Plan de Ayala. Zapata wilde de landerijen van de grootgrondbezitters onteigenen en teruggeven aan de kleine boeren en aan de pueblos. Zapata heeft zich nooit anarchist genoemd maar was in belangrijke mate beïnvloed door de anarchistische ideeën van de broers Enrique en Ricardo Flores Magon en door de geschriften van Kropotkin. In 1915 wist hij na verovering van grote delen van Morelos het gebied te herverdelen zoals hij in zijn plan had voorgesteld en tegelijk de levensstandaard voor de boerenbevolking aanzienlijk te verbeteren.

Madero benoemde de meedogenloze generaal Victoriano Huerta tot legerleider, om zo Zapata te kunnen bestrijden. Huerta liet Madero vervolgens uit de weg ruimen en benoemde zichzelf tot president. Het jaar 1914 werd gekenmerkt door een felle strijd tussen het federale leger en de opstandelingen. Het boerenleger van Zapata in Morelos en de troepen van Villa in het noorden, bestookten voortdurend het Mexicaanse leger. Aanvankelijk steunde Villa weliswaar Huerta, maar al snel keerde hij zich van hem af. Villa wilde in de eerste plaats de macht van de grootgrondbezitters doorbreken.

Paarden

Zapata en Villa waakten ervoor geen grootschalige confrontaties met het federale leger aan te gaan. Vaak werd een hinderlaag opgezet of werden snelle verrassingsovervallen uitgevoerd op kleine legereenheden in het veld of op dorpen en kleine steden die in handen waren van het leger. Omsingelde legereenheden werden tot overgave gedwongen of men ging de strijd aan.

Soldaten die zich aan Zapata overgaven werd de keuze gegeven zich bij hem aan te sluiten of de wapens in te leveren en naar huis te gaan. Officieren werden in de meeste gevallen geëxecuteerd. Na de inname van een stad of dorp werd het stadhuis in brand gestoken waarna men weer verdween. Expedities van het leger op zoek naar de zapatistas bleven meestal zonder resultaat. Na een snelle terugtocht naar eigen gronden, verdwenen de zapatistas geruisloos in de anonimiteit van het dagelijkse boerenleven.

Verrassingsaanvallen

Het leger van Zapata bestond uit zo’n drie- tot vijfduizend man, meestal opererend in groepen variërend van tientallen tot enkele honderden. Een belangrijke voorwaarde om snel tot actie te kunnen overgaan, was al vervuld: vrijwel alle soldaten hadden voor hun dagelijks werk al de beschikking over een paard. Wel was het voor Zapata aanvankelijk lastig om aan voldoende wapens te komen. Door haciendas van landeigenaren te overvallen werd het wapenbezit aangevuld. Het doel van Zapata’s guerrillatactiek was door telkens verrassingsaanvallen uit te voeren, de vijand te verzwakken. Daarbij was het zaak de eigen verliezen zo laag mogelijk te houden. Bij voorkeur vielen de zapatistas te paard aan op voor hen bekend terrein, ongeschikt voor de inzet van grote vijandige legers of infanterietroepen. Doorslaggevend voor de successen van de zapatistas was dat de soldaten geworteld waren in de lokale bevolking en er deel van uitmaakten. Zowel met voedselvoorziening als logistiek met de toelevering van paarden, werden de zapatistas door de lokale bevolking ondersteund. Het federale leger bestond uit vijfentwintigduizend man, veelal gelegerd in garnizoensplaatsen. Van daaruit beperkte het zich vooral tot het controleren van de omgeving.

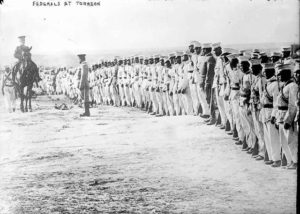

Met weliswaar de beschikking over kanonnen, was het vooral gericht op een negentiende eeuwse, Europese wijze van oorlog voeren, zoals tijdens de Napoleontische oorlogen en de Frans-Duitse oorlog van 1870: een massale inzet van infanterietroepen die slag konden leveren met een soortgelijke tegenstander. Het Mexicaanse leger kon daarom niet effectief reageren op tegenstanders die van guerrillatactieken gebruik maakten. Met name in woestijngebieden en de bergen bleek het leger niet doeltreffend te kunnen opereren.

Treinen

Door eveneens guerrilla-aanvallen uit te voeren kon Pancho Villa met zijn leger – variërend van vijf- tot zestienduizend man – in de staat Chihuahua een groot gebied bestrijken. Villa paste graag een overrompelingstactiek toe op zijn tegenstanders, door massaal met zijn manschappen, in volle galop al schietend de vijand tegemoet te treden. Dezelfde aanvalstactiek werd al eerder door de Noord-Amerikaanse Comanche- en Apache-indianen toegepast.

Villa vergrote zijn mobiliteit aanzienlijk door gebruik te maken van gekaapte treinen. Zo kon binnen enkele dagen honderden kilometers verderop een aanval worden uitgevoerd. De paarden van de soldaten werden in de trein gestald, de mannen namen plaats op de daken van de wagons. Met een tweede trein volgden de vrouwen van de soldaten. Villa hechtte er aan dat de echtgenotes en vriendinnen van de soldaten gedurende een veldtocht altijd in de nabijheid waren. Zo werd de desertie van villistas beperkt en de kans op verkrachtingen in veroverde pueblos verkleind. Vrouwen zorgden meestal voor de maaltijden en verzorgden de gewonden. Sommige vrouwen, de soldaderas, reden en vochten in de voorste linies mee.[4]

In het leger van Zapata was het zeker niet ongewoon wanneer een vrouw een officiersrang vervulde.[5]

Van Villa wordt beweerd dat hij zo nu en dan een trein kaapte achter de vijandelijke linies, deze volstopte met explosieven en vervolgens op de vijand liet inrijden. Bekend is dat Villa meerdere malen verslagen tegenstanders zonder pardon liet executeren.

Triomf en dood

Zapata en Villa hadden geen presidentiële ambities. Hun grootste symbolische triomf was het moment waarop beide mannen in 1914 onder het gejuich van tienduizenden, gezamenlijk Mexico City binnenreden, nadat ze tegenstanders Carranza en Obregón hadden verslagen. In de jaren twintig kwam de Partido Revolucionario Institucional, voortgekomen uit de revolutie, aan de macht. Enkele punten uit het Plan de Ayala werden weliswaar gerealiseerd, maar de landhervormingen werden niet doorgevoerd op de wijze zoals Zapata ze zich had voorgesteld. Nog steeds is de Partido Revolucionario Institucional de toonaangevende partij in Mexico, maar deze is vervallen tot een brede sociaaldemocratische beweging zonder revolutionair elan. Zapata heeft in Mexico nog steeds een legendarische status. In 1919 werd hij in een ingewikkeld complot in een val gelokt. Bij het oprijden van het dorpsplein van Chinameca, werd hij door veronderstelde medestanders doodgeschoten. Pancho Villa trof in 1923 hetzelfde lot. Nadat hij bij een plaatselijke bank goud had opgenomen, werd hij in de hoofdstraat van het plaatsje Parral door tegenstanders onder vuur genomen. Opmerkelijk detail: Villa was niet te paard, maar reed op dat moment in zijn auto, een Dodge.(6)

Noten

Noten

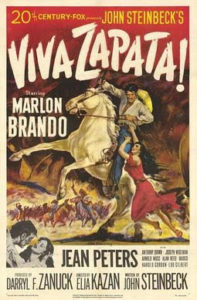

[1] De bekendste film is Viva Zapata! (1952) van regisseur Elia Kazan, naar een scenario van John Steinbeck, met Marlon Brando als Zapata, helaas een wat minder goede film van Kazan.

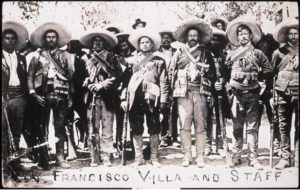

Pancho Villa is in veel Hollywoodproducties meestal vervallen tot een karikatuur, zoals in Villa Rides (1968) met Yul Brynner als Villa, of in Pancho Villa (1972) met Telly Savalas in de hoofdrol. Villa was een ijdele man en niet wars van publiciteit. Een aantal malen werden zijn acties vastgelegd door Amerikaanse filmploegen en in drie films speelde Villa zichzelf.

Een uitstekende documentaire over de Mexicaanse Revolutie en haar betekenis, The Storm that Swept Mexico (2011), is te vinden op Youtube en bevat veel authentieke filmopnames uit de revolutiejaren. Zie hieronder.

[2] Op het verloop van de revolutie kan in het bestek van dit artikel slechts kort worden ingegaan. Enkele titels over de Mexicaanse Revolutie: Ronald Atkin, Revolution! Mexico 1910-1920 (1969); Adolfo Gilly, The Mexican Revolution (1983), Robert E. Quirk, The Mexican Revolution 1914-1915 (1960). Over Zapata zijn o.a. verschenen: Peter E. Newell, Zapata of Mexico (1979); Robert P. Millon, Zapata (1969); John Womack Jr., Zapata and The Mexican Revolution (1969). De Amerikaanse auteur John Reed (de latere schrijver van Ten Days that Shook the World) reisde enige tijd mee met de troepen van Pancho Villa en deed daarvan verslag in zijn boek Insurgent Mexico (1914).

[3] Porfirio Díaz (1830-1915) sleet zijn laatste jaren in Parijs. Hij ligt begraven op Cimetière du Montparnasse (15 e Division) in Parijs.

[4] Tijdens de revolutie ontstond het volksliedje La Adelita. Het lied is een eerbetoon aan de soldaderas en wordt in Mexico nog steeds gespeeld.

[5] Zo werd de onderwijzeres Dolores Jiménes y Muro (1848-1925) in 1914 brigadegeneraal in het leger van Zapata. Ze werkte mee aan het opstellen van het Plan de Ayala en was redactrice van de krant La Voz de Juárez.

[6] De auto waarin Villa werd gedood is te bezichtigen in het Francisco Villa Museum in Chihuahua, Mexico. Zie https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Villa_Museum

The Storm that Swept Mexico

Why Trump’s Racist And Neo-Fascist Campaign Strategy Resonates In 21st Century America

With the November election just around the corner, Donald Trump is raising the level of his racist and fascist rhetoric to new heights, fully aware that his hate speech and authoritarian overtures resonate with a large segment of white Americans in 21st century who, as surreal and obscene as this may sound, would have preferred that time stood still, stuck either in the era of the plantation system or at least at a time when whites in this country felt so superior to minorities that they could discriminate and oppress the “Other” without fear of getting into trouble with the law, let alone become witness to public outcries over police brutality, systemic racism, and demands for gender and racial equality.

Indeed, it is the awareness of the existence of a very large segment of white Americans in 21 st century who wish to roll back the clock on account of their growing insecurities and fears about the[ir] future that prompts Trump to sound ever more racist and project ever more the image of a strong man as time moves closer to election time. In doing so, his hope is that even moderate white voters might be stirred into feeling the need to join in on what he obviously hopes they may come to recognize and appreciate, just like his traditional base of white supremacists does, as an urgent “patriotic” campaign on the part of the “Great White Leader” to save [white] America’s soul. As for his rich supporters, he doesn’t care one way or another about the impact of his rhetoric on them because he knows they will continue supporting him as long as he maintains a steadfast course of lavishing them with gifts, such as huge tax cuts, deregulation policies, etc.

Trump’s attempt to outdo himself was most evident at his Minnesota rally a few days ago– perhaps the most extreme example so far of how far the “Great White Leader” is ready and willing to go in order to spread fear and promote hate as tactical means of securing another electoral victory in a country sharply divided into different political tribes.

And make no mistake about it: reliance on fear, hate, and violence have always been the political tools of fascists of all stripes.

Trump declared to Minnesotans that Biden would turn their state into a “refugee camp.” He warned them of “sleepy Joe Biden’s extreme plan to flood” Minnesota with refugees from Somalia, while denigrating at the same time the election of Rep. Ilhan Omar, who came to the United States as a child refugee from Somalia, calling her an “extremist”. To this insidious racist rhetoric, his fanatical base from below responded by screaming “send her back.”

Trump’s racist rhetoric hit a crescendo when he let his crowd know that they are supporting him because of their “good genes.”And to further upgrade his neo-fascist profile with his adoring crowd, he said it was “a beautiful thing” when journalist Ali Velshi got struck by a rubber bullet while covering a peaceful protest.

All in all, Trump’s performance at the Minnesota rally on September 18 was an act stolen from the electoral campaign of Hitler and his Nazi party. The only thing he fell short from saying was that anyone who did not support him should be deprived of civic rights and sent to prison or concentration camps.

No rational human being can fail to see that Trump is a racist with strong fascist impulses, but even critics of Trump fail to see or properly acknowledge that the “Great White Leader” employs the rhetoric of racism and fascism because there is a huge market for it in 21 st century America!

The Political Economy Of Saving The Planet. An Interview With Noam Chomsky & Robert Pollin

What needs to be done to advance a successful political mobilization on behalf of a global Green New Deal—a program that includes emissions reductions, expands renewable energy sources, addresses the needs of vulnerable workers, and promotes sustainable and egalitarian economic growth? Political scientist C. J. Polychroniou spoke with Noam Chomsky and economist Robert Pollin, who has been at the forefront of the fight for an egalitarian green economy for more than a decade, to discuss prospects for change, the connections between climate and the COVID-19 pandemic, and whether eco-socialism is a viable option for mobilizing people in the struggle to create a green future.

This conversation was adapted from Chomsky and Pollin’s new book Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet.

C. J. Polychroniou: How does the coronavirus pandemic, and the response to it, shed light on how we should think about climate change and the prospects for a global Green New Deal?

Noam Chomsky: At the time of writing, concern for the COVID-19 crisis is virtually all-consuming. That’s understandable. It is severe and is severely disrupting lives. But it will pass, though at horrendous cost, and there will be recovery. There will not be recovery from the melting of the arctic ice sheets and the other consequences of global warming.

Not everyone is ignoring the advancing existential crisis. The sociopaths dedicated to accelerating the disaster continue to pursue their efforts, relentlessly. As before, Trump and his courtiers take pride in leading the race to destruction. As the United States was becoming the epicenter of the pandemic, thanks in no small measure to their folly, the White House cabal released its budget proposals. As expected, the proposals call for even deeper cuts in healthcare support and environmental protection, instead favoring the bloated military and the building of Trump’s Great Wall. And to add an extra touch of sadism, the budget promotes a fossil fuel ‘energy boom’ in the United States, including an increase in the production of natural gas and crude oil.”

Meanwhile, to drive another nail in the coffin that Trump and associates are preparing for the nation and the world, their corporate-run EPA weakened auto emission standards, thus enhancing environmental destruction and killing more people from pollution. As expected, fossil fuel companies are lining up in the forefront of the appeals of the corporate sector to the nanny state, pleading once again for the generous public to rescue them from the consequences of their misdeeds.

In brief, the criminal classes are relentless in their pursuit of power and profit, whatever the human consequences. And those consequences will be disastrous if their efforts are not countered, indeed overwhelmed, by those concerned for “the survival of humanity.” It is no time to mince words out of misplaced politeness. “The survival of humanity” is at risk on our present course, to quote a leaked internal memo from JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest bank, referring specifically to the bank’s genocidal policy of funding fossil fuel production.

One heartening feature of the present crisis is the rise in community organizations starting mutual aid efforts. These could become centers for confronting the challenges that are already eroding the foundations of the social order. The courage of doctors and nurses, laboring under miserable conditions imposed by decades of socioeconomic lunacy, is a tribute to the resources of the human spirit. There are ways forward. The opportunities cannot be allowed to lapse.

Robert Pollin: In addition to the fundamental considerations that Noam has emphasized, there are several other ways in which the climate crisis and the coronavirus pandemic intersect. One underlying cause of the COVID-19 outbreak—as well as other recent epidemics such as Ebola, West Nile, and HIV—has been the destruction of animal habitats through deforestation and human encroachment, as well as the disruption of the remaining habitat through the increasing frequency and severity of heat waves, droughts, and floods. As the science journalist Sonia Shah wrote in February 2020, habitat destruction increases the likelihood that wild species “will come into repeated intimate contact with the human settlements expanding into their newly fragmented habitats. It’s this kind of repeated, intimate contact that allows the microbes that live in their bodies to cross over into ours, transforming benign animal microbes into deadly human pathogens.”

It is also likely that people who are exposed to dangerous levels of air pollution will face more severe health consequences than those breathing cleaner air. Aaron Bernstein of Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment states that “air pollution is strongly associated with people’s risk of getting pneumonia and other respiratory infections and with getting sicker when they do get pneumonia. A study done on SARS, a virus closely related to COVID-19, found that people who breathed dirtier air were about twice as likely to die from the infection.”

A separate point that was raised over the worst months of the COVID-19 pandemic was that the responses in the countries that immediately handled the crisis more effectively, such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore, demonstrated that governments are capable of taking decisive and effective action in the face of crisis. The death tolls from COVID-19 in these countries were negligible, and normal life returned relatively soon after governments imposed initial lockdowns. Similarly decisive interventions could successfully deal with the climate crisis where the political will is strong and the public sectors are competent.

There are important elements of truth in such views, but we should also be careful to not push this point too far. Some commentators have argued that one silver lining outcome of the pandemic was that, because of the economic lockdown, fossil fuel consumption and CO2 emissions plunged alongside overall economic activity during the recession. While this is true, I do not see any positive lessons here with respect to advancing a viable emissions program that can get us to net zero emissions by 2050. Rather, the experience demonstrates why a degrowth approach to emissions reduction is unworkable. Emissions did indeed fall sharply because of the pandemic and the recession. But that is only because incomes collapsed and unemployment spiked over this same period. This only reinforces the conclusion that the only effective climate stabilization path is the Green New Deal, as it is the only one that does not require a drastic contraction (or “degrowth”) of jobs and incomes to drive down emissions.

Climate Change Intensifies Inequality: An Interview With Gregor Semieniuk

This is part of PERI’s economist interview series, hosted by C.J. Polychroniou.

C.J. Polychroniou: You studied International Relations in Germany, at the Technische Universität Dresden, but ended up pursuing graduate studies in economics in the USA. What drew you into the “dismal science?”

Gregor Semieniuk: In Dresden, the program’s content spanned economics, public law and political science. What intrigued me about economics was that on the one hand it seemed necessary to grapple with the most intractable global issues of the time: for instance, why it was so difficult to increase most countries’ material affluence, how renewable energy could quickly replace the existing energy supply, and of course how the 2007-08 financial crisis and ensuing economic turmoil could be explained. On the other, my economics classes tended to provide straightforward answers to questions that were obviously more multi-faceted, like that a minimum wage was (categorically) to be discouraged because it diminished welfare. From my political science classes I knew that it was good practice to seek out contending theories to analyze the same problem through different lenses so as to gain a deeper understanding. I wanted to learn about contending theories also in economics, but there seemed to be only one theory, so-called neoclassical economics, and its strengths and weaknesses weren’t explicitly discussed. My search for a program that satisfied my curiosity led me to look to the USA, and ultimately to the New School for Social Research, with its famous teaching of a plurality of theoretical approaches. So I went there for my graduate studies. Of course, one thing I learned soon enough was that neoclassical economics and its offshoots can be more nuanced in their assumptions and conclusions. Yet, this does not replace the more variegated approaches and points of analytical departure that the full gamut of ideas in economics (in history and present) has to offer.

CJP: Your primary research areas are in environmental and ecological economics and in economic growth. Can you briefly spell out the connection between climate change and the economy? And, more specifically, in what ways does climate change threaten economic stability and growth?

GS: Climate change is driven by greenhouse gas emissions, that are mainly caused by combusting fossil fuels and from changes in land use (think intensive agriculture or deforestation). Fossil fuels in particular have been historically tightly interlinked with economic growth. Their qualities and quantities are arguably a key factor behind the industrial revolutions in today’s rich countries. Luckily, however, while energy is a fundamental input into any economic activity, there are increasingly good alternatives to fossil fuels to supply that energy without or with much lower emissions, such as modern solar and wind energy, and a growing variety of devices compatible with the electricity they supply, such as electric vehicles and heat pumps.

At an abstract level, the interaction of economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions can be thought of as economic growth causing greenhouse gas emissions to rise. The resulting climate change “dampens” or eventually reverses economic growth through negative impacts on productivity, profitability, capital stock and human lives. More concretely, climate change poses difficult problems and threatens human wellbeing and livelihood in many ways. There are direct impacts, such as lower agricultural productivity or sea level rises. More indirect impacts intensify social problems and conflicts. To give you one example, up to two thirds of Bangladesh’s population are at risk of being impacted by sea level rise by the mid-21st century. This does not mean permanent inundation but increased exposure to flooding and salinity that make it harder to earn a living on agriculture, or risks destroying coastal non-agricultural production sites and homes. The resulting increased migration from coastal to inland communities can exacerbate social conflicts and urban poverty there, ultimately threatening social and economic stability. In the USA, up to 40 million people could be exposed to such hazards by 2100.[1] Of course, here there are much more resources available that could be used to protect communities from these impacts, so the context in which climate change impacts occur matters.

Isabella Marie Weber – The Peculiarities Of China’s Economic Model

Isabella Weber – PERI Research Associate and Research Leader in China Studies; Assistant Professor of Economics

This is part of PERI’s economist interview series, hosted by C.J. Polychroniou. The Series: https://www.peri.umass.edu/peri-economist-interview-series

Read Isabella Weber’s bio here.

C.J. Polychroniou: How did you get into economics?

Isabella Maria Weber: I got into economics through my interest in politics, in particular global questions. I realized that the political is inherently economic and the economic inherently political. If we want to understand how we can work towards positive change politically, we have to understand the material foundations of our society. If we want to make sense of the major shifts in our global political system, we have to understand the long-term economic dynamics. Coming from this angle, economics for me must take the form of political economy.

CJP: What do you consider to be the main issue in your research?

IMW: The broad question that motivates my research is how we can make sense of the major changes in the global economy that are unfolding in front of our eyes – at a dramatically accelerated pace since the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the Industrial Revolution in the late 18thcentury, we have lived in a world of a globalizing capitalist economic system, first under British than under U.S. hegemony. This phase is coming to a close with the gradual rise of China – not necessarily to one of dominance but to a more eye-level position. In my research, I pursue two related questions that aim to make a small contribution to this broad challenge: First, I have studied the intellectual foundations behind China’s economic reforms that set the country on the path of its current ascent. Second, I am leading a research project in which we examine the long-term evolution of global export patterns across the last and present era of globalization. The aim here is to understand path dependency and path defiance in the global division of labor. This theme grew out of earlier work on the US-China trade imbalance. In a third strand of my research, I have been investigating foundational questions of the nature of money and the driving forces of international trade for the purpose of placing my work on firmer theoretical grounds.

CJP: Why did you choose to specialize on the Chinese economy?

IMW: I am answering your questions as we watch the global economy collapse under the threat of COVID-19. There is no question that the political and economic power relations between the U.S. and China are changing. Many people in the U.S. and Europe alike are reacting to this uncertain dynamic with fear and, unfortunately, with increasingly racist, anti-Chinese sentiments. In order to work toward a peaceful navigation of the deep structural changes in the world economy, I believe that there is an urgent need for a better understanding of the logic of China’s political economy. Instead of measuring China’s system against the European or American experiences or some standard economics model, we need to study China’s path on its own grounds, while taking into account at the same time its global connectedness. I have specialized in the Chinese economy for the very purpose of making some kind of a contribution to this project.

CJP: How real is the so-called Chinese economic miracle?

IMW: The Oxford English Dictionary defines a “miracle” as a “marvelous event not ascribable to human power.” China’s economic development of the last four decades is certainly astonishing and as such marvelous. But it is by no means the result of some overnight wonder created by supernatural agency or luck. According to Maddison estimates of 2001, China accounted for about one third of the world’s GDP in 1850. Its share had fallen to below 5 percent in 1950, when China was one of the poorest countries in the world. Today China is responsible for about a fifth of the world’s GDP. These are rough measures, but the trend is obvious. China’s Communist revolution was about much higher aspirations than economic development. But it was clear from the beginning that industrialization and higher living standards were core requirements. Of course, China gave up long ago on Mao’s vision of revolution. But the pursuit of economic progress has continued across dramatically different political phases since 1949. China’s gradual return to a more prominent position in the world economy is not the result of a miracle, but of decades of hard work and heterodox economic policymaking. In a forthcoming book of mine, I argue that China’s economic leaders learned key lessons from the history of economic warfare in the 1930s and 1940s. At the heart of this strategy is the articulation of clear broad goals which are being pursued by flexibly utilizing prevailing economic dynamics and structures.

CJP: How did China manage to liberalize its economy while avoiding shock therapy, which is pretty much what happened in virtually all transition economies in Eastern Europe, Russia, and Latin America?

IMW: We often imagine of China’s gradual economic reforms as having been without an alternative. In fact, the 1980s marked a crossroads in the recent history of China and of global capitalism, as I show in my forthcoming book “How China Escaped Shock Therapy.” China too had very concrete plans for far-ranging overnight liberalizations. Had China implemented the policy of “shock therapy,” it would most likely have generated the same devastating results that we have observed elsewhere, but on a much larger scale. China would have mirrored Russia’s fall, but starting from a much lower level.

The basic premise of shock therapy is that all institutions of direct state control over the economy must be destroyed to make space for the market. Instead, China pursued a strategy of market creation that utilized the institutions of the planned economy. It kept the core of the planned industrial economy working, while transforming the old institutions into market players by first allowing for market activities on the margins. This strategy is manifested in the dual-track price system. Under this system, state-owned enterprises and farmers had to deliver the state-set quotas at a state-set price, but if they managed to produce more, they could market their surplus at market prices. In this way, China’s economy was gradually marketized under active bureaucratic guidance by reorienting its core economic institutions from the plan to the market. Non-essentials were liberalized first. Surpluses as well as sectors producing non-basic goods were non-essentials. They could be completely marketized without immediately endangering the stability of the whole system. Yet, the marketization of these non-essential areas unleashed a dynamic that fundamentally transformed the whole political economy, including its core.[1] As a result of this strategy, China kept much closer control over core sectors of the economy, such as energy, steel, finance and infrastructure. This has allowed China to respond in a fine-grained and targeted way to the 2008 global financial crisis, and to the current economic collapse in light of COVID-19.

CJP: Could/should the Chinese model be emulated by other developing countries?

IMW: China had a very different starting point from most other developing countries today. From a longue durée perspective, China could build on a very long history of bureaucratic market creation and participation. Tools derived from the statecraft of playing the market were utilized during the revolutionary struggles and again in the reform era. Considering the more immediate context, the Mao era had laid strong foundations for China’s take off in terms of education, literacy, public health and basic industrialization. Most developing countries do not have those preconditions. It would therefore not make sense to simply copy China’s model. But there is a deeper reason for not copying China’s model that emerges from China’s own experience. It is extremely important to realize that China, too, did not simply copy foreign models. Chinese researchers and officials, in collaboration with international partners, studied carefully the experience of various other countries and drew lessons for the country’s own specific situation, adapting the insights to its concrete conditions, often with major problems in the process. This approach of careful study of the prevailing local condition and adaptation of foreign experiences is what other developing countries can learn from China. But there is no panacea that works for all. The Beijing Model should not replace the Washington Consensus. The lesson is that there is no easy universal solution, no policy package that can fix it all.

CJP: What’s your view on Trump’s trade war with China? More generally, do you think the Chinese economy poses threats to the U.S. economy and other countries’ economies? If so, should they do anything about it?

IMW: I think that the trade war is an extremely dangerous policy. If any further proof was needed – and I don’t think there is, COVID-19 is demonstrating in a morbid fashion just how closely integrated the world is with China, and vice versa. In the 1980s China retreated from its revolutionary ambitions and embarked on a path of reform using its state capacity to reintegrate into the global market. Since the 1990s, we have been living through a second peak of globalization in modern times. The last globalization ended with the First World War. The present one is collapsing as I am writing. In such a situation, we need international collaboration, not war of any kind. I don’t think the Chinese economy, taken by itself, poses a threat to the U.S. or to other countries. Crises of this historical moment don’t have a nationality; they lie in the nature of the global system. The real threat results from the exploitation of this crisis by nationalists and racists. To confront this threat, we have to improve our understanding of China, instead of feeding into scapegoat narratives.

Reference:

[1] I spell this out in greater detail in this interview: https://www.peri.umass.edu/economists/isabella/item/1206-the-making-of-china-s-economic-reforms