Chomsky: Trump’s Actions On Syria Reflect The Foreign Policy Of A Con Man

Donald Trump’s handling of U.S. foreign policy with Syria has baffled and angered both the diplomatic and military establishments in the United States. Nonetheless, he continues to maintain power as “an effective con man who has a good sense of what animates his voting base,” Noam Chomsky argues in the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows.

Donald Trump’s handling of U.S. foreign policy with Syria has baffled and angered both the diplomatic and military establishments in the United States. Nonetheless, he continues to maintain power as “an effective con man who has a good sense of what animates his voting base,” Noam Chomsky argues in the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows.

Trump rose to power with the aid of vitriolic but disingenuous “anti-establishment” rhetoric that appealed to millions of disgruntled voters. Essentially, Trump promised to “drain the swamp” in Washington, and to advance a domestic and foreign policy agenda serving U.S. national interests and those of “average people.” However, Trumpism in practice has meant something different: rolling back the remaining tatters of liberalism on the domestic front, sharpening racist xenophobia, facilitating the rise of white nationalism and eroding longstanding global alliances that the United States formed after the end of World War II. Truthout’s C.J. Polychroniou asked Chomsky to share his thoughts on Trump’s stance toward Syria, the impeachment effort against the president and the dynamics of the 2020 election.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, since coming to office, Trump has shown on numerous occasions that he is not a normal foreign policy president. But can you make any sense out of his stance toward Syria?

Noam Chomsky: The first of Trump’s recent steps was to withdraw the small U.S. contingent that was a deterrent to Turkey’s expansion of its invasion of Syria and to authorize Erdoğan’s plans to extend his atrocities and ethnic cleansing of Syrian Kurds. His second step was to move U.S. troops to “secure” the oil-producing areas. The latter, apparently after he was told about the oil, is easy to understand. He has held all along that our only standing interest in the Middle East is to “secure” its oil for our own benefit. As for the first step, we can only speculate, but it seems quite likely that the motive is what guides him consistently: How will the action affect me? Trump is an effective con man who has a good sense of what animates his voting base. In this case, he presumably expected (correctly it seems) that withdrawing a few hundred troops would appeal to the sector of the population that resonates to his message that America is foolishly expending its blood and treasure to help “unworthy” people who don’t even thank us for our sacrifices on their behalf, and that Trump is the first president to stand up for the suffering American people instead of giving everything away to foreigners out of stupidity (or treachery).

It’s worth recalling that repeated polls have shown that Americans vastly overestimate the scale of foreign aid — and recommend that it be considerably higher than it actually is (putting aside what constitutes “aid”).

Much has been written and said about the betrayal of the Kurds, a U.S. ally in the war against ISIS (also known as Daesh). This isn’t, however, the first time that the U.S. has betrayed the Kurds and other former allies.

Betrayal of the Kurds has been virtually a qualification for office since Ford-Kissinger abandoned the Kurds to the mercy of Saddam Hussein when they were no longer needed. Reagan went so far as to support his friend Saddam’s chemical warfare campaign against Iraqi Kurds, seeking to shift the blame to Iran and blocking congressional efforts to respond to these hideous crimes. Clinton’s method was to provide the arms for the murderous government assault on Turkish Kurds, which killed tens of thousands, wiped out 3,500 towns and villages, and drove hundreds of thousands from their homes. (See Noam Chomsky, The New Military Humanism, Chapter 3. London: Pluto Press, 1999). Clinton’s flood of military aid increased along with the shocking crimes, as Turkey became the prime recipient of American arms (outside of Israel-Egypt, a separate category). Read more

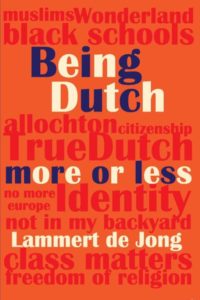

The Dutch Black School: They Are Not Us

Lammert de Jong – Being Dutch. More or less. In a comparative Perspective of USA and Caribbean Practices Rozenberg Publishers 2010. ISBN 978 90 3610 210 0 – The complete book will be online soon.

‘An Inconvenient Truth’

In the Netherlands, ‘black’ is not black; it is ‘non-western’, including Moroccan, Turkish, and people of Caribbean origin, lumped together as allochtons. In government statistics, schools with more than 70% allochton pupils are generally classified as a black school; schools with less than 20% allochton pupils are graded as white. The black school concept is also used in relation to the surrounding neighborhood. Schools with more pupils of non-western origin than expected in view of the composition of the neighborhood are labeled blacker or, in the case of an over-representation of white pupils, whiter. A deviation of 20% or more between neighborhood and school population classifies a school as too white or too black (Forum, 2007). The number of primary schools with more than 70% allochton pupils is increasing; in Dutch nomenclature: the schools are becoming blacker.

The Dutch black school is a perfidious contraption that locks in children of non-western origin, while its black label flags an underlying apartheid syndrome to underscore for the True Dutch – intentionally or not – how different these allochtons are. Yet the black school touches an open nerve in the Netherlands, a sensitive reality that surpasses its statistical definition. On the one hand the black school reeks of apartheid, which the Dutch so bravely contest when occurring elsewhere in the world. On the other hand the True Dutch are well aware that their entitlement and unencumbered access to white schools is at stake when school segregation is tackled in earnest. So far Dutch counteraction is limited to research and some experimental desegregation projects.

The Dutch black school is embedded in the particular Dutch school system that funds public-secular as well as private-denominational schools. Once, the Dutch school system was driven by the accommodation of different beliefs. On the strength of their belief – church-religion or secular ideology – parents wanted a school for their children that adhered to the values, doctrines, and rules of their faith, and paid for by the state. [Note: In 2009 the Netherlands’ Council of State pointed out that publicly financed orthodox religion-based schools may refuse teachers who identify with a particular gay life style. The fact that a teacher is gay is not sufficient to deny a position, but if he or she is in a same sex relation and married in church or city hall, that may suffice, as such contravenes the orthodox rule that marriage is a holy sacrament between one man and one woman]

Denominational and non-religious schools emphasized particularity, a distinctiveness that corresponded with religious doctrines or ideological orientations. The principle of Freedom of Education (Onderwijsvrijheid) is enshrined in the Netherlands Constitution, art. 23. Over the years parents have come to believe that they are entitled to choose a specific school for their children, which is a travesty of the freedom to choose a particular type of school, based on denominational or secular definition.

Dutch politics wavers when coming to grips with the effects the black school brings – quite literally – home. Most parents don’t set out intending to discriminate, which makes a noble difference, and legally enforced segregation is not on the books. Nonetheless a segregated white-black educational system has become a reality, with most True Dutch children in better schools and having better school careers, and children of allochtons at the other end. And that with long lasting effects after the school years have come to an end. This type of school segregation stigmatizes New Dutch children for life, while reinforcing an allochton footprint that will divide the nation for years to come. Although most political parties assert that integration is the major social issue of our time, they fail to confront the black school with a sense of urgency. Dutch politics still has to acknowledge that the black school emblematizes the allochton population in the Netherlands with an explicit signature: They are not Us.

Black schools are a common feature in most major Dutch cities. So far the black school does not stand out in Dutch politics as a problem that must be solved urgently by law, regulation or in the courts. The black school seems more of an inconvenient truth than a critical social or political issue. To an outsider this must be surprising, given that the Netherlands is known for its rock-solid liberal reputation. How come then that the Netherlands has become a segregated nation? And do they discriminate against people of color? Do the Dutch not know how to handle the ethnic complexities of today’s multi-cultural society? Or is it a lack of compassion for those who do not belong to the white Dutch tribe: Discrimination or not, my children first. Or is it merely a matter of social-economic stratification, a distinction between advantaged and disadvantaged children, so that the Dutch black school is just a myth (Vink, 2010)?

“Trump Specializes In Showmanship Not Statecraft”: An Interview With Andrew Bacevich

Andrew J. Bacevich. Professor Emeritus of International Relations and History. Photo: Boston University

What are the founding principles of U.S. foreign policy? Was the U.S. ever isolationist as mainstream diplomatic history claims? And what about Donald Trump’s foreign policy? Is he a normal foreign policy president? Is he in favor of U.S. global expansion? Is China emerging as the new global empire? Andrew Bacevich, Professor Emeritus of International Relations and History at Boston University and now president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft tackles the above questions in the interview below. A retired US army Colonel who fought in the Vietnam War an lost a son in the Iraq war, Bacevich is the author of numerous works on U.S. foreign policy, including among many others, Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War (2010); The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War (2005); Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country (2013; and of the forthcoming book The Age of Illusions: How America Squandered Its Cold War Victory.

C. J. Polychroniou: I would like to start by asking you to reflect on the founding principles of U.S. foreign policy, which many regard as “geopolitical isolationism” and “unilateralism,” and whether this is what the U.S. has practiced for most of its history.

Andrew Bacevich: The overarching theme of U.S. policy from the very founding of the Republic has been 1780s opportunistic expansionism. As far back as the 1780s, the Northwest Ordinances had made it clear that the United States had no intention of confining its reach to the territory encompassed within the boundaries of the original thirteen states. While the U.S. encountered sporadic resistance during the course of its remarkable ascent, virtually all of it proved to be futile. With the notable exception of the failed attempt to incorporate Canada into the Union during the War of 1812, expansionist efforts succeeded spectacularly and at a remarkably modest cost. Already by mid-century, the United States stretched from sea to shining sea.

In 1899, the naturalist-historian-politician-sometime soldier and future president Theodore Roosevelt neatly summarized the events of the century just drawing to a close: “Of course, our whole national history has been one of expansion.” When TR uttered this rarely acknowledged truth, a fresh round of expansionism was underway, this time reaching beyond the fastness of North America into the surrounding seas and oceans. Among Europeans, a profit motivated but racially justified imperialism was in full flower. The United States was now joining in. The year before, U.S. forces had invaded and occupied Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Guam, and the island of Luzon across the Pacific. Within two years, the United States had annexed the entire Philippine Archipelago. Within four years, with Roosevelt now in the White House, U.S. troops arrived to garrison the Isthmus of Panama where the United States, subsequent to considerable chicanery, was setting out to build a canal. Soon thereafter, to preempt any threats to that canal, successive administrations embarked upon a series of interventions throughout the Caribbean. Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson had no desire to annex Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic, they merely wanted the United States to control what happened in those small countries, as it already did in nearby Cuba. While President Trump’s recent bid to purchase Greenland from Denmark may have has failed, Wilson – perhaps demonstrating greater

skill in the art of the deal – did persuade the Danes in 1917 to part with the Virgin Islands for the bargain price of $25 million.

The U.S. preference for operating unilaterally and its determination to avoid getting entangled in European power politics during this period is of much

less significance than narrative of expansion, as Americans persistently sought more — more territory, more markets, more abundance. Read more

Noam Chomsky And Robert Pollin: If We Want A Future, Green New Deal Is Key

Climate change is by far the most serious crisis facing the world today. At stake is the future of civilization as we know it. Yet, both public awareness and government action lag way behind what’s needed to avert a climate change catastrophe. In the interview below, Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin discuss the challenges ahead and what needs to be done.

Noam Chomsky is Professor Emeritus of Linguistics at MIT and Laureate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Arizona. Robert Pollin is Distinguished University Professor of Economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Chomsky, Pollin and Polychroniou are co-authors of a book on climate change and the Green New Deal, forthcoming with Verso in Spring 2020.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, let me start with you and ask you to share your thoughts about the uniqueness of the climate change crisis.

Noam Chomsky: History is all too rich in records of horrendous wars, indescribable torture, massacres and every imaginable abuse of fundamental rights. But the threat of destruction of organized human life in any recognizable or tolerable form — that is entirely new. The environmental crisis under way is indeed unique in human history, and is a true existential crisis. Those alive today will decide the fate of humanity — and the fate of the other species that we are now destroying at a rate not seen for 65 million years, when a huge asteroid hit the earth, ending the age of the dinosaurs and opening the way for some small mammals to evolve to pose a similar threat to life on earth as that earlier asteroid, though differing from it in that we can make a choice.

Meanwhile the world watches as we proceed toward a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions. We are approaching perilously close to the global temperatures of 120,000 years ago, when sea levels were 6-9 meters higher than today. Glaciers are sliding into the sea five times faster than in the 1990s, with more than 100 meters of ice thickness lost in some areas due to ocean warming, and current losses doubling every decade. Complete loss of the ice sheets would raise sea levels by about five meters, drowning coastal cities, and with utterly devastating effects elsewhere — the low-lying plains of Bangladesh for example. This is only one of the many concerns of those who are paying attention to what is happening before our eyes.

Climate scientists are certainly paying close attention, and issuing dire warnings. Israeli climatologist Baruch Rinkevich captures the general mood succinctly: After us, the deluge, as the saying goes. People don’t fully understand what we’re talking about here…. They don’t understand that everything is expected to change: the air we breathe, the food we eat, the water we drink, the landscapes we see, the oceans, the seasons, the daily routine, the quality of life. Our children will have to adapt or become extinct…. That’s not for me. I’m happy I won’t be here.

Yet, just at the time when all must act together, with dedication, to confront humanity’s “ultimate challenge,” the leaders of the most powerful state in human history, in full awareness of what they are doing, are dedicating themselves with passion to destroying the prospects for organized human life. Read more

To Confront Climate Change, We Need An Ecological Democracy

Climate change represents the biggest existential crisis that has ever faced the human race. However, we have yet to come to terms with the moral, political and economic dimensions of the climate crisis. As we confront climate change, we must ask: What would real climate justice look like? And what is the connection between the pursuit of true democracy and the battle to stave off a climatic change catastrophe? Marit Hammond, a lecturer in environmental politics at Keele University in the U.K., advocates for the necessity of an “ecological democracy” in order to meet the climate emergency urgently and sustainably. In this interview, Hammond offers insights on what this new form of democracy would look like and how we can get there.

C.J. Polychroniou: The challenge of climate change has been confronted so far on both political and economic grounds. Yet fewer people are engaging in conversations about the moral element of climate change. Isn’t global warming, first and foremost, a moral issue?

Marit Hammond: It is. However, it is important to stress that this moral dimension is not separate from, but rather stretches into the political and economic dimensions — for it is not just about private individuals’ moral behavior.

Climate change is a moral issue insofar as it is knowingly caused by human actions, and in turn causes significant, existential harm — avoidable harm — to humans, other species, precious cultures and ecosystems. As is widely known, threats such as crop failures, weather extremes and sea level rise threaten the quality of life, if not life itself, particularly of those who already have the least resources to draw on to manage their lives. It is those who cannot afford to protect themselves against heat waves that die or suffer severe health problems; those already living in precarious, [severe] weather-prone regions are forced to migrate elsewhere and make themselves economically vulnerable in the process. Although climate change is a complex phenomenon at the planetary level, it is causing suffering in the lives of concrete individuals — as well as the irreversible loss of countless species and unique ecosystems.

If there were a more direct cause-effect relationship, it would go without saying that causing such harm would be immoral. The only difference with climate change is that the actions that cause it are only indirectly related to the suffering it causes, and distributed amongst the global population — everyone who lives in an industrial society contributes to climate change. Thus, it is more difficult to determine intentionality and agency. Moral blame applies where harm is caused intentionally or through negligence — where there is agency to either cause or avoid [dealing with] it. In the case of climate change, this is the clear case, where people intentionally and knowingly lead high-emission lifestyles, such as driving, flying, or otherwise consuming more, or in more highly emitting ways, than they need.

Yet to a significant extent, individuals in industrialized societies actually have very little agency over their lives in these regards. Even those who want to be morally responsible, who have every intention to stop climate change and avert the suffering it causes, are forced to live the kinds of life the socio-economic system around them expects and demands; they inevitably rely on the agricultural, industrial and energy systems that are much more to blame. To make a living, they mostly have no choice but to contribute to a growth-oriented economy, whose ideology of exploitation (of people and nature alike) is the real underlying cause of climate change.

Thus it is important to remind ourselves of the moral dimension of climate change so that people don’t just see it as a managerial challenge to embrace — like another phase of modernization, which the growth economy has to adapt to but can ultimately benefit from — but as a prompt to get very angry about this wider system we are forced to live in. As concern about climate change is now growing amongst Western populations, it has become fashionable to consume ‘greener’ products and to object to the use of plastics, for example. These responses fit into a picture of embracing the need for societies to overhaul themselves, to become better by becoming greener — the spirit of ecological modernization. They do not, however, challenge consumerism per se, accept the need for general restraint and degrowth, or push for radical change at the level of the socio-economic system and its exploitative ideology. If it is at that level that climate change is caused, this is where the moral outrage people feel needs to be directed at. Now that we know about climate change, we have a moral responsibility not just to drive less and carry a reusable coffee mug, but to condemn the political and economic structures that are the real driver of the problem. Read more

Herinnering aan André Köbben (1925-2019)

19 augustus 2019. Op 13 augustus, vorige week dus, overleed André Köbben. Hij was mijn leermeester, in allerlei opzichten. Ik ben vier jaar zijn assistent geweest in de jaren zestig van de vorige eeuw, ik ben in 1974 bij hem gepromoveerd. Vandaag wordt hij gecremeerd, in Leiden, waar hij woonde. Er is veel over hem te vertellen, en ik vermoed dat ik dat op deze plaats ook nog wel zal doen. Maar ter herinnering aan hem druk ik op deze dag een ‘gesprek’ met hem af. Ik voerde dat begin 2012, ruim zeven jaar geleden dus, voor een tijdschrift: Tijdschrift over Cultuur en Criminologie, waarin het later dat jaar (het septembernummer) werd geplaatst.

Een gesprek voor het Tijdschrift over Cultuur & Criminaliteit? Je bent van harte welkom, zegt André Köbben aan de telefoon, maar hij geeft me huiswerk op. Hij stuurt me de tekst toe van Bedrog in de wetenschap, die hij begin januari (2012) heeft voorgedragen bij de Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen. Ook vraagt hij me de nieuwe bundel met criminologische opstellen van Frank Bovenkerk door te nemen: Een gevoel van dreiging. Het ging hem niet om het motto van de bundel, ontleend aan Köbben zelf en met karakteristieke köbbiaanse ironie verwoord:Zelfs zou ik mij willen verstouten u, lezer, de vaderlijke raad mee te geven: in uw eigen belang en dat van anderen, waag u nóóit aan echte voorspellingen. Nee, ik moet lezen wat Bovenkerk heeft geschreven over de Noorse massamoordenaar Anders Breivik, de politieke moorden op Pim Fortuyn en Theo van Gogh, de spray shooting in Alphen aan den Rijn en de aanslag op de koninklijke familie in Apeldoorn in 2009.

De overeenkomsten tussen beide onderwerpen dringen niet meteen tot me door, maar na een kort college zie ik de analogie. André Köbben en ik ontmoeten elkaar bij hem thuis, in zijn gerieflijke Leidse studeerkamer. Opvallend netjes opgeruimd voor een werkkamer, maar wel met overal stapels boeken en notities – een onderzoeker aan het werk. Begin februari. Buiten is het heftig vriesweer en schijnt een oogverblindende zon. In de jaren 1960 ben ik vier jaar zijn assistent geweest en hebben we vaak zo tegenover elkaar gezeten, op zijn kamer in de Amsterdamse Spinhuissteeg, later aan de Keizersgracht; boeken, tijdschriften, blocnotes en losse papieren tussen ons in. Het voelt vertrouwd en eigenlijk volstrekt gewoon, zo hoort het – André aan het woord, ik met een aantekeningenboekje. Nu tutoyeren we elkaar, dat was destijds ondenkbaar. Ook hij heeft zich voorbereid, er ligt een cv voor me klaar, knipsels, tijdschriftartikelen.

In zijn lezing over bedrog valt Köbben met de deur in huis: ‘Op 8 september 2011 kwam het bedrog van Diederik Stapel in de openbaarheid. Het kwam voor iedereen als een donderslag bij heldere hemel.’ Velen denken dat het gaat om een uitzonderlijk geval en sommigen, onder wie de rapporteur over de zaak Stapel, beweren zelfs dat er sprake is van het ‘omvangrijkste bedrog ooit’. Köbben laat zien dat dit niet waar is, maar wat hem boeit is het stereotiepe karakter van zulke reacties. Net als het feit dat je allerlei commentatoren op ziet duiken die onmiddellijk menen te weten wat de oorzaak zou zijn geweest van Stapels bedrog. De gedachte erachter is dat je zulke incidenten eigenlijk zou moeten kunnen voorkomen, dat er maatregelen getroffen zouden kunnen worden om bedrog in de wetenschap uit te roeien. Daar zit een bepaalde logica achter en wel de ‘logica van de risicosamenleving’ – de term wordt gebruikt door Frank Bovenkerk en hij bespreekt het begrip in zijn bundel. De zin van het huiswerk begint te dagen. Als er een gruwelijke aanslag zoals die in Noorwegen gepleegd wordt – heel letterlijk: een donderslag bij heldere hemel – klinken er meteen stemmen die de overheid verantwoordelijk stellen: we hadden die Breivik toch wel eerder kunnen ontmaskeren als gewetenloze killer? De werkelijkheid is ingewikkeld, de misdaadbevorderende factoren die in het leven van Anders Breivik kunnen worden aangewezen, vind je ook bij duizenden anderen en daar gaat het blijkbaar niet mis. Toch wordt er een commissie ingesteld die één of een paar veronderstelde oorzaken belicht waar snel iets aan kan worden gedaan. Helaas is het onduidelijk hoeveel rampen in de toekomst kunnen worden voorkomen door zulke ad-hocmaatregelen. Bovenkerk zegt gelaten: ‘Het wachten is op de volgende calamiteit.’ Read more