The Resurgence Of Political Authoritarianism: An Interview With Noam Chomsky

Following the end of World War II, liberal democracy began to flourish in most countries in the Western world, and its institutions and values were aspired to by movements and individuals under authoritarian and oppressive regimes. However, with the rise of neoliberalism, both the institutions and the values of modern democracy came rapidly and continuously under attack in an effort to extend the profit-maximizing logic and practices of capitalism throughout all aspects of economic and social life.

Sketched out in broad outlines, this story explains the resurgence of authoritarian political trends in today’s Western societies, including the rise of far-right movements whose followers feel threatened by the processes unleashed by neoliberal economic policies. In the former communist countries and in the non-Western world, meanwhile, authoritarianism is also on the rise, partly as a residue of authoritarian legacies, and partly as a reaction to perceived threats posed to national culture and social order by global capitalism.

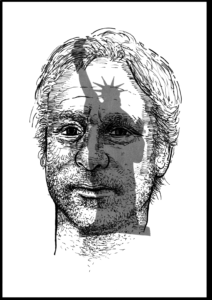

Is it possible to counter this rise in extreme populism? In this exclusive Truthout interview, the world-renowned linguist and public intellectual Noam Chomsky — the author of more than 100 books and thousands of academic articles and popular essays — offers his unique insights on this and more, bringing into the analysis issues and questions that are rarely addressed in the current debates taking place today about the resurgence of political authoritarianism.

C.J. Polychroniou: In 1992, Francis Fukuyama published an intellectually embarrassing book titled The End of History and the Last Man, in which he prophesied the “end of history” after the collapse of the communist bloc, arguing that liberal democracy would become the world’s “final form of human government.” However, what has happened in this decade in particular is that the institutions and values of liberal democracy have come under attack by scores of authoritarian leaders all over the world, and extreme nationalism, xenophobia and “soft fascist” tendencies have begun reshaping the political landscape in Europe and the United States. How do you explain the resurgence of political authoritarianism in the early part of the 21st century?

Noam Chomsky: The “political landscape” is indeed ominous. While today’s political and social circumstances are much less dire, still they do call to mind Antonio Gramsci’s warning from Mussolini’s prison cells about the severe crisis of his day, which “consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born [and] in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

One morbid symptom is the resurgence of political authoritarianism, a highly important matter that is properly receiving a great deal of attention in public debate. But “a great deal of public attention” should always be a warning sign: Does the shaping of the issues reflect power interests, which are diverting attention from what may be more significant factors behind the general concerns? In the present case, I think that is so, and before turning to the very significant question of the resurgence of political authoritarianism, I’d like to bring up related matters that do not seem to me to receive the attention they merit, and in fact are almost totally excluded from the extensive public attention.

It’s entirely true that “the institutions and values of liberal democracy are under attack” to an unusual extent, but not only by authoritarian leaders, and not for the first time. I presume all would agree that primary among the values of liberal democracy is that governments should be responsive to voters. If that is not the case, “liberal democracy” is a farce. Read more

Towards A Progressive Political Economy In The Aftermath Of Neoliberalism’s “Creative Destruction”

Abstract

The article argues that, after 45 years of ‘neoliberal destruction’, the time is ripe for moving forward with the adoption of a new set of progressive economic policies (beyond those usually associated with classical Keynesianism) that will reshape advanced societies and the global economy on the whole by bringing back the social state, doing away with the predatory and parasitic practices of financial capital, and charting a course of sustainable development through a regulatory regime for the protection of the environment while promoting full employment, workers’ participation in the production process, and non-market values across a wide range of human services, including health and education.

Policy recommendations

• Capitalism is an inherently unstable socioeconomic system with a natural tendency toward crises, and thus must be regulated; especially the financial sector, which constitutes the most dynamic and potentially destructive aspect of capital accumulation.

• Banks, as critical entities of the financial sector of the economy, are in essence social institutions and their main role or function should be to accept deposits by the public and issue loans. When banks and other financial institutions fail, they should be nationalized without any hesitation and all attempts to socialize losses should be immediately seen for what they are: unethical and undemocratic undertakings brought about by tight-knit linkages between governments and private interests. In periods of crisis, the recapitalization of banks with public funds must be accompanied by the state’s participation in banks’ equity capital.

• Markets are socially designed institutions, and as such, the idea of the “free market” represents one of the most pervasive and dangerous myths of contemporary capitalism. From antiquity to the present, trade was based on contracts and agreement between government authorities and was spread through the direct intervention of the state. Human societies without markets cannot thrive. However, markets often function inefficiently (they create oligopolies, give rise to undesirable incentives and cause externalities), and they cannot produce public goods in sufficiently large quantities to satisfy societal needs. Therefore, state intervention into markets is both a social need and a necessary moral obligation.

• The economic sphere does not represent an opposite pole from the social sphere. The aim of the economy is to improve the human condition, a principle that mandates that the process of wealth creation in any given society should not be purely for private gain but, first and foremost, for the support and enhancement of economic infrastructure and social institutions for further economic and social development; with the ultimate goal being the attainment of a decent standard of living for all citizens. Free education and health care should be accessible to everyone, along with the right to a job. Indeed, full employment (See Pollin, 2012) must become a key pillar of a progressive economic policy in the 21st century.

• Workplaces with a human-centered design must replace the current authoritarian trends embodied in most capitalist enterprises, and participatory economics (social ownership, self-managing workers, etc.,) should be highly encouraged and supported.

• The improvement of the quality of the environment (with key priorities being the protection and preservation of ecosystems in oceans and seas and the protection of forests and natural wealth, in combination with policies seeking to address the phenomenon of climate change) ought to be a strategic aim of a progressive economic policy, realizing that the urgency of environmental issues concerns, in the final analysis, the very survival of our own species. Read more

Marcel ten Hooven ~ De ontmanteling van de democratie

Marcel ten Hooven begint zijn boek De ontmanteling van de democratie met te memoreren welke drie boeken hij leest tijdens het schrijven en welke lessen hij eruit trok voor de democratie. Philip Roths boek The plot against America over ‘de krachten die de democratie en de rechtsstaat ondermijnen, aanvankelijk als een giftig maar reukloos gas dat vanonder de deur komt’ komt terug in het eerste deel van Ten Hoovens boek, dat gaat over het dreigend verval van de democratie. In het tweede deel ‘Hoe de kunst van het samenleven verstoord raakt – en wat er aan te doen’ is Ten Hooven schatplichtig aan Marten Toonders De zwarte Zwadderneel, dat ondanks alle zwartgalligheid laat zien dat het toch nog niet zo erg is gesteld met onze democratie, want in landen met een ‘langdurige democratische en rechtsstatelijke traditie krijgen autocratische of dictatoriale krachten niet zomaar een kans’. Uit Theodicee van F.B. Hotz leent hij de moraal, dat de democratie nooit af is en dat we erover moeten nadenken, praten en discussiëren. Aan dit proces wil Ten Hooven een bijdrage leveren.

Maar Ten Hooven is vooral schatplichtig aan de Franse politieke filosoof Claude Lefort en diens definitie van ‘de lege plaats van de macht’: een plek die niemand kan claimen, de plaats van de macht is symbolisch leeg. Macht mag nooit definitief door een meerderheid worden bezet. De politiek is de publieke ruimte waarin verschillende standpunten worden uitgewisseld. Macht kan alleen tijdelijk worden gerepresenteerd. Democratie is een lerend systeem, nooit af. Het zoekt naar een middelpunt kracht op partijen. Hierin onderscheidt de democratie zich als politiek systeem van totalitarisme.

‘De ontmanteling van de democratie’ gaat in op de ideologische armoede van de volkspartijen, het asociale neoliberalisme, de valse beloftes en de zondebokpolitiek van het populisme met Trump als voorbeeld, maar ook op de groeiende ongelijkheid, de verminderde solidariteit en de invloed van nepnieuws. Voor Marcel ten Hooven schuilt de essentie van de democratie in haar maatschappelijke betekenis. Naast een stelsel van rechten om iedereen een stem te geven, is zij een vorm van beschaving die het mogelijk maakt fatsoenlijk met elkaar om te gaan. Het betekent vooral rekening te houden met minderheden en hun ook ruimte te bieden; het gaat meer om de bescherming van minderheden dan om de vorming van een meerderheid (zie ook Halleh Ghorashi: http://rozenbergquarterly.com/halleh-ghorashi/) in een door Felix Merites georganiseerd debat) en het recht dat het hoogste gezag is in een democratie. In bestuurlijke zin betrekt de democratie burgers bij besluitvorming over maatschappelijke kwesties; in morele zin helpt zij de samenleving de ambiguïteit in het dagelijkse leven te verdragen. De democratie legt bij ieder individu een verantwoordelijkheid voor het geheel, dat maakt de democratie breekbaar en ook fragiel ‘doordat zij zelf haar eigen tegenmachten kan maken en breken en doordat zij zowel op de vorming als op de inperking van macht is gericht’.

De westerse democratieën zijn de laatste decennia instabiel geworden: het westerse liberale waardenstelsel met zijn normen voor democratie, rechtsorde en menselijke waardigheid staat onder druk. Niet alleen van buitenaf (terrorisme, autoritaire regimes) maar ook van binnenuit ( populistische reactie) en zelfs van bovenaf (Trump) wordt zij ondermijnt. De liberale democratie wordt ook in Europa aangevallen door autocraten (Rusland, Polen, Hongarije, Tsjechië, Turkije). Read more

Christian Madsbjerg ~ Filosofie in een tijd van big data

Zijn big data en algoritmes de ultieme bron voor succes, zoals Gijs van Oenen betoogt in ‘Overspannen democratie. Hoge verwachtingen, paradoxale gevolgen’ (zie: http://rozenbergquarterly.com/gijs-van-oenen-overspannen-democratie-hoge-verwachtingen-paradoxale-gevolgen/) ? Is het zo dat big data leidt tot meer inzicht en succes? Heeft menselijke interpretatie nog wel nut in het tijdperk van het algoritme? De filosoof, politiek wetenschapper en veelgevraagd adviseur van Fortune 500-bedrijven Christian Madsbjerg laat aan hand van voorbeelden zien dat de wereld uit veel meer bestaat dan een serie algoritmes. Veel van de grootste succesverhalen komen niet voort uit wiskundige analyses, maar zijn het resultaat van menselijke betekenisgeving en betrokkenheid met cultuur. Elk inzicht blijft krachteloos als we niet het menselijk gedrag, het denken erbij betrekken. Een kritische benadering is nooit ‘zo revolutionair en actueel geweest als nu’. Als we onze culturele kennis afdanken, dan gaat dan ten koste van de toekomst van de mens.

Christian Madsbjerg houdt in zijn boek ‘Filosofie in een tijd van big data’ een vlammend betoog voor cultureel engagement, diepgang, ervaring en de geesteswetenschappen en ontmaskert de tirannie van het getal en de wetenschappelijke focus op direct nut. “Nooit eerder is onze cultuur zo sterk verleid door de belofte van kunstmatige intelligentie, machinaal leren en cognitieve computing. Nooit eerder is onze wereld van overlappende politieke, financiële, sociale, technische en ecologische systemen zo sterk met elkaar verbonden geweest.” Madsbjerg houdt een warm pleidooi voor de studie geesteswetenschappen, die ons tot nieuwe ideeën kan brengen, cultureel engagement dat de basis vormt van de methode die hij ‘betekenisgeving’ noemt, en een leidraad kan zijn in een steeds veranderende omgeving. Het kan niet alleen inzicht geven, maar op langer termijn veel profijtelijker zijn, ‘zowel voor je bankrekening als voor je leven – dan een beperking tot de benauwde werkelijkheid van de big data’, de ‘dunne data’, die ons willen begrijpen op basis van wat we doen, abstracte data, terwijl ‘dikke data’ de hele context meenemen, data van de betekenisgeving, de context van de feiten.

Madsbjerg haalt Silicon Valley aan als een bedrijf waar alleen dunne data gelden, met een ‘obsessie voor kwantificering’ en veel wordt gesproken over ‘disruptie’ (een breuk tussen een ‘voor’ en een ‘na’, een natuurwetenschappelijke manier van denken, waarbij iets waar is tot het tegendeel wordt bewezen). Big data zijn gericht op correlatie en niet op causaliteit en zijn niet geïnteresseerd in het ‘waarom’. Men gaat op zoek naar info en ervaringen die ons een gevoel van bevestiging en erkenning geen. Alhoewel de innovaties van Silicon Valley ook grote voordelen bieden, is het gevaar groot om zonder betekenisgeving te werken. Dit staat in groot contrast met de intellectuele traditie. Read more

Goodbye Regulations, Hello Impending Global Financial Crisis

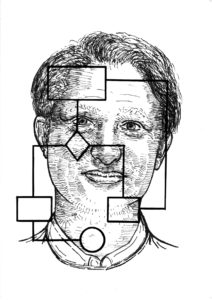

Ten years after the last financial crisis, Republicans — with backing from many Democrats — have made sure that Wall Street can return to its old ways of doing business by repealing the Dodd-Frank Act, which acted up to now as a very mild regulatory regime to rein in the predatory nature of financial capital. The decision to repeal Dodd-Frank was justified on the grounds that it put a break on economic growth. Gerald Epstein, professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, argues that this is not true at all. In this exclusive Truthout interview, Epstein notes that it is now very likely that the “toxic, speculative activities” of the Wall Street crowd will return with a menace, thereby preparing the groundwork for the next global financial crisis.

C.J. Polychroniou: Following the financial crisis of 2008, a bill was passed in 2010 under the Obama administration that sought to contain risks in the US financial system. The bill, which was sponsored by US Sen. Christopher Dodd and US Rep. Barney Frank, was rather weak as a regulatory regime. Nonetheless, it was severely criticized by conservatives. Donald Trump delivered a mixed message in running for president, railing against the big banks and Hillary Clinton’s connections to Wall Street, while at the same time promising more deregulation. Now, Congress has passed and President Trump has signed into law a comprehensive financial deregulation law, “The Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act.” In addition, Trump-appointed financial regulatory agencies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have implemented policies to loosen regulations further on a variety of financial institutions and activities. The backers of rolling back Dodd-Frank have claimed that financial deregulation will increase economic growth and provide more credit to households and business. First, what were the weaknesses of the Dodd-Frank Act, and did it actually contribute to anemic economic growth, as its Republican critics like Paul Ryan and others are arguing?

Gerald Epstein: The main weakness of the Dodd-Frank Act is that it did not break up the “too big to fail” financial institutions. As a result, these large financial institutions retained the power to blackmail the public to bail them out the next time there is a financial meltdown and, as we have seen since Trump was elected, to buy off enough politicians to roll back the weak financial regulations that were passed. More generally, Dodd-Frank had way too many loopholes that resulted from financial sector lobbying so that it could never be implemented in its strongest form.

No, Dodd-Frank did not contribute to anemic growth. There is no evidence of this. Anemic growth was largely due to the legacy of the financial crisis itself, in which a great deal of household wealth was decimated, and to the continuing austerity policies that the Republicans were able to force on a weak-kneed and Wall Street-bedazzled Obama administration. On top of these factors are the long-term structural problems of the US economy related to the high level of inequality — itself largely due to the oversized power of Wall Street — and to the widespread disinvestment of US multinational corporations from the US economy, among other factors. If anything, Dodd-Frank worked against some of these tendencies, and thereby helped to sustain the long economic recovery that the Trump administration is now benefiting politically from. Read more

EU’s Debt Deal Is “Kiss of Death” For Greece

After eight long and extremely painful years of austerity due to gigantic rescue packages that were accompanied by brutal neoliberal measures, in Athens, the “leftist” government of Alexis Tsipras has announced that the era of austerity is now over thanks to the conclusion of a debt agreement with European creditors.

After eight long and extremely painful years of austerity due to gigantic rescue packages that were accompanied by brutal neoliberal measures, in Athens, the “leftist” government of Alexis Tsipras has announced that the era of austerity is now over thanks to the conclusion of a debt agreement with European creditors.

In the early hours of June 22, a so-called “historic” deal on debt relief was reached at a meeting of Eurozone finance ministers after it was assessed that Greece had successfully completed its European Stability Mechanism program, and that there was no need for a follow-up program.

The idea that Greece’s bailout programs can be considered a success adds a new twist to the government’s Orwellian doublespeak, given the fact that the country has experienced the biggest economic crisis in postwar Europe, with its gross domestic product (GDP) having shrunk by about a quarter, and reporting the highest unemployment rate (currently standing at 20.1 percent) of all European Union (EU) states.

On top of that, the ratio of the country’s public debt to gross GDP has risen from 127 percent in 2009 to about 180 percent, a development which has essentially turned Greece into a debt colony, leading to pressing demands that all valuable public assets be sold — including airports, railways, ports, sewerage systems, and gas and energy resources. Indeed, since the start of the bailout programs, Greek governments have been trying hard to outdo one another on the privatization front in order to satisfy the demands of the official creditors, the EU and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Still, the current pseudo-leftist Syriza government has proven to be the most servile of Greek governments to creditors.

Arguments for privatization aside, the deadly combination of higher debt and declining GDP had most economists convinced quite early on that austerity was killing Greece’s economy, and that a debt write-off would be at some point absolutely necessary for medium- and long-term recovery. However, Germany and its northern European allies had diametrically opposed this idea, insisting on even stronger doses of austerity, while balking at the prospect of a debt write-off. Read more