- by: Edward Kellow, Mathew A. Varghese & Deepa Pullanikkatil

What is communication?

What is communication?

What constitutes communication has always been historically contingent. It is never easy to pin down and designate ‘what is communication is’ and ‘what it is not’. But it is obvious that communication has taken many forms and evolved: from cave art to town criers, from street theatre to newspapers and television, and finally to digital engagement. One may argue that none of the aforementioned has influenced the world as much as digital engagement, making information available at your fingertips, changing the power dynamics for communicators, and transforming the way people can be influenced and their attitudes shaped. Here we try to explore issues of how digital engagement will thrive in a cynical, nationalist, populist world and raise the pertinent question: Does digital engagement encourage better decision-making, or merely reinforce prejudice?

The impact of Brexit and the USA presidential election

Two major events that gave “post truth” a linguistic footing were Brexit and the election of USA President Donald Trump. They showed that the world has indeed changed, and exposed the fact that people are making decisions based on emotions and beliefs. So, in the new world we live in, is evidence less important than beliefs? In the UK referendum on the EU, the #leave campaign claimed falsely that leaving the EU would mean that £350 million could be given to the National Health Service (NHS). After Brexit, thousands of people signed online petitions to have the result of the referendum reviewed. Gillian Tett, author of ‘The Silo Effect’ wrote, “The Brexit vote was decided on the basis of emotion – and the Remain camp failed to give voters a really positive vision of Europe.”

The impact of digital engagement on decision-making

Digital engagement was meant to make information more accessible to more people. But it has also made it possible for anyone to publish anything they want without having to provide evidence. As a result people find it hard to tell the difference between truth and lies. Fake news propagated on Facebook about the Pope supporting Trump and Trump’s tweets changing the direction of media coverage, makes one wonder whether digital engagement is encouraging propaganda and disinformation? Or whether people are making decisions based on emotions and do not care much about the facts?

In an interview with the Financial Times in June 2016 Adair Turner former Head of the Financial Services Agency (FSA) said, “I was once a confident optimist and rationalist. I also used to believe that everybody could be persuaded by rational argument. I’ve increasingly realised that people need mythologies, people need nationalisms and people need religions.”

Power to the powerless?

Digital engagement was thought to level the playing field and give power to the powerless (as in Arab Spring). It was believed to be a way to re-engage voters, in particular young people, with politics, giving a voice to the voiceless. Instead, it has given the powerful another weapon to acquire even more power. It favours those who shout loudest, responsible for the growth of ‘populism’ and government by Twitter. Today, anyone with a smartphone can voice an opinion, create an opinion train and broadcast beliefs. Communication becomes a political process when this happens, as opinion formation and counter-commonsensical visions gain popularity and contribute to undermining democracy. Perhaps this may have inspired the OECD, which has recently called on schools to teach young people how to identify fake news. Read more

Aangezien de eerste druk van mijn boek Tegendraads (Rozenberg Publishers, 2007, 978 90 5170 853 0) is uitverkocht, heb ik dankbaar gebruik gemaakt van de mogelijkheid om dit boek als e-book te herdrukken. De reden daarvoor is dat politie en justitie, hoewel er de laatste jaren meerdere gerechtelijke dwalingen aan het licht zijn gekomen, niet willen toegeven dat zij fouten maken. Laat staan dat zij daarvan willen leren teneinde nieuwe blunders te voorkomen. Waardoor ze nog steeds levens van onschuldige mensen ruïneren.

Aangezien de eerste druk van mijn boek Tegendraads (Rozenberg Publishers, 2007, 978 90 5170 853 0) is uitverkocht, heb ik dankbaar gebruik gemaakt van de mogelijkheid om dit boek als e-book te herdrukken. De reden daarvoor is dat politie en justitie, hoewel er de laatste jaren meerdere gerechtelijke dwalingen aan het licht zijn gekomen, niet willen toegeven dat zij fouten maken. Laat staan dat zij daarvan willen leren teneinde nieuwe blunders te voorkomen. Waardoor ze nog steeds levens van onschuldige mensen ruïneren.

Aangezien er in de afgelopen tien jaar in de beschreven zaken wel nieuwe ontwikkelingen zijn geweest, zal aan de desbetreffende hoofdstukken nieuwe tekst worden toegevoegd. In de oorspronkelijke tekst zijn ook type- en taalfouten verbeterd.

Het eerste hoofdstuk, getiteld Over de auteur, is geschreven door mede-auteur Willem de Haan. Vandaar dat hierin over mij in de derde persoon wordt geschreven en citaten van mij worden aangehaald.

Zowel in de nieuwe als oude tekst heeft Bart FM Droog bij de e-bookversie de rol vervuld van redacteur. Dankzij hem is de tekst (nog) duidelijker geworden, waarvoor mijn hartelijke dank.

Lees hier (Nog steeds) tegendraads van Harrie Timmerman, het ruim 300 pagina’s tellende boek van Harrie Timmerman, in de Verplichte kost-reeks van de NPE, als gratis downloadbaar pdf-document.

Er is inmiddels ook een webversie-verschenen, waarin enkele tv-documentaires en radio- en tv-interviews met Timmerman zijn opgenomen. Zie:

“Ideas can and do change the world,” says historian Rutger Bregman, sharing his case for a provocative one: guaranteed basic income. Learn more about the idea’s 500-year history and a forgotten modern experiment where it actually worked — and imagine how much energy and talent we would unleash if we got rid of poverty once and for all.

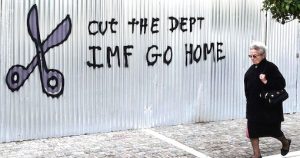

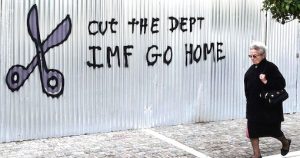

Photo: occupy.com

For the last several months, Greece’s international creditors – the European Union (EU) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – had been at a standoff over debt relief, budget targets and various reforms, including taxes and pensions, thereby delaying the completion of a long overdue bailout review that should have been done in October 2016. The standoff added extra pressures to an economy that has been in recession for eight straight years, and even revived fears of a “Grexit” as bank runs had returned in full steam. In the meantime, the Syriza-led government of Alexis Tsipras was playing the role of a mere observer in a tug-of-war between two institutions that are in full control of the country’s finances, and merely trying to accommodate the demands of both sides.

Since the start of the current financial and economic crisis in Greece, which goes back to 2008 (although the actual outbreak of the debt crisis occurs in early 2010), the country’s GDP has shrunk by about 26 percent. Unemployment jumped to as high as 28 percent in 2013, and has now stabilized at 23 percent, but more than 42 percent of the population has “dropped below the poverty threshold of 2005.”

This harsh reality is the price the country is paying for its fiscal derailment as a member of a currency union (the euro) and the imposition of three consecutive bailout programs by the EU and the IMF. These bailouts have been accompanied by draconian measures of fiscal consolidation (austerity) and a radical neoliberal agenda which includes sharp cuts in wages, salaries and pensions, liberalization of the labor market and blanket privatization.

From the beginning, the bailout plans were never intended to rescue the Greek economy, but rather to avoid a financial meltdown on the continent, as several European banks had recklessly loaned to the public sector since Greece adopted the euro in 2001. Indeed, virtually all of the funds that have been provided to Greece since 2010 have gone towards the repayment of international loans – first to the European banks, and then to the country’s official creditors – rather than towards the economy.

But let’s return to the present: the standoff between EU and IMF over the “best way” to deal with Greece’s current financial and economic catastrophe, which finally came to an end a couple of weeks ago, with the Greek government agreeing to a new round of austerity measures which amount, essentially, to a fourth memorandum.

Spreading False Hopes About Recovery and Vague Promises About Debt Relief

Having grossly miscalculated the impact of the fiscal policies it proposed on the Greek economy, the IMF has been extremely reluctant to join in the third bailout program (agreed to and signed by the pseudo-leftist Syriza government of Alexis Tsipras), sensing that Greece will never be able to repay its loans. The country is essentially bankrupt, and the prospects for a return to the private credit markets any time soon are not very promising, as there are no signs of recovery on the horizon. At some point, small rates of growth will inevitably be registered solely because of the economy having hit rock bottom, but this is not the case at present.

Still, illusions of a recovery have been the hallmark of both the Syriza government and of the conservative government that preceded it. But this should not be surprising. Spreading false hopes to the citizens of a bankrupt nation that has lost its sovereignty is the last refuge of political scoundrels, of governments and their officials who have opted to become lackeys of the international elite rather than lead their people to resistance and to the overthrow of financial regimes imposing debt bondage.

Indeed, for the last few months, senior-level officials in the Syriza government, such as Minister of Economy and Development Dimitri B. Papadimitriou, were propounding that growth had made a comeback and that the crisis was over before the official statistics for the fourth quarter of 2016 were finally released in early March 2017. However, those figures showed the Greek economy had contracted again by 1.2 percent.

Read more

Gerald Epstein is Professor of Economics and a founding Co-Director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

With Donald Trump in power, US society is likely to witness in the next four years a regression of social progress and environmental damage unlike anything the country has seen in the course of its modern history. In this context, progressives have their hands full and only massive resistance may halt the march to the precipice. But any effective strategy of resistance requires linking theory and praxis. It is imperative that we understand the dynamics in US society that brought Trump to power. It is imperative that we also understand what Trump actually represents and whether Trumpism is here to stay. Then we can think of the most effective ways to challenge the sort of political gestalt in Trump’s miasma.

In this exclusive interview, radical political economist Gerald Epstein addresses these issues and offers his insights on how we can resist Trumpism. Gerald Epstein is professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and author of scores of books and articles on the political economy of contemporary capitalism.

C.J. Polychroniou: The rise of Donald Trump to power took a lot of people by surprise, although there were strong indications for a long time now that the conditions in the United States were ripe for the emergence of an authoritarian leader. Still, the actual reasons for the rise of a fake populist in power remain rather puzzling, so I’d like to start by asking for your views on what led to Trump’s stunning victory.

Gerald Epstein: As you say, conditions of working people have been deteriorating in the US for many decades now, creating fertile ground for leaders outside the political establishment to offer anti-elitist explanations and offer apparent solutions for people desperate for them. This helps to explain both the Bernie [Sanders] and the Trump phenomena. But when you add on top of these the deep racist, sexist and xenophobic undercurrents that have always been present in American society and which are low-hanging fruit just waiting to be picked and utilized by a demagogue, you have Donald Trump…. In short, the Democratic Party’s embrace of neoliberalism, which continued with Hillary Clinton, is a big part of the story. Still, one should not forget the devastating roles that the Republican Party played in the last eight years as they gained more and more power — not just in Congress, but also in state and local governments in many parts of the country. They were able to do this by exploiting Democratic failures, but also by a money-fueled long-term strategy by extreme right-wing capitalists, such as the Koch brothers and others. Without this massive financial input and a long-term strategy, this victory would not have occurred. More specifically, their electoral strategy in the last four to eight years … was to incapacitate the government from helping poor and working-class people, while enriching the powerful and the elite — and then blame the Democrats for the fall out. Sam Brownback, governor of Kansas, and Scott Brown, governor of Wisconsin, as well as the Republican Party in Congress in Washington, DC, pursued this seemingly kamikaze approach to governing. Amazingly, it succeeded. It shoved poor and working people more and more into the dirt as cuts were made to public investments, benefits, living standards. But rather than blaming the Republicans, many of these Americans voted against the Democrat — Hillary Clinton.

This means that only a very weak party (the Democrats), a very weak candidate (Hillary Clinton) and a huge amount of luck — the rise of Trump, [former] FBI Director James Comey’s last-minute attack on Clinton and an Electoral College system that delivered the presidency to Trump despite losing the vote by 3 million votes — could have ultimately ended in Trump’s victory. But the fact that he would have gotten so close even without these intervening factors underlines the deep rot in the system, including the Democratic Party’s neoliberalism and the role of massive amounts of right-wing money combined with a long-term, revolutionary political strategy.

But to see the real underlying causes of Trumpism, we have to dig a bit deeper. All of the above is taking place in a context of a 30- to 40-year transformation of the US’s place in the global economy — a transformation that would have required an economic policy directed toward managing it for the working classes and the poor, rather than for finance and the elite, which is what happened as I described earlier. The relative decline of the US as a site of production, the rise first of Japan, China, India and other countries in the developing world, and the intermittent competition with Europe and other countries meant that the economic institutions that the US relied on in the early post-World War II era could no longer deliver the goods to both working-class Americans and the capitalists. The Democrats and Republicans both went with the capitalists and a neoliberal faith in markets, rather than engaging in the reshaping of US institutions to thrive in a more competitive global environment. The mixture of financialization and subsidized support for US multinational corporations, and all kinds of free rides for elites, ultimately brought us to the age of Trumpism.

Read more

Prof. Fatima Suleman

On 16 May Prof. Fatima Suleman gave her inaugural lecture as the new Professor to the Prince Claus Chair in Development and Equity at Utrecht University, entitled: Affordability and equitable access to (bio)therapeutics for public health. Prof. Suleman works at the University of Kwazulu Natal in South Africa and connects the theme of development and equity with accessibility of medicine, pharmacy and health economics.Read the highly interesting text of the inaugural lecture or watch the video of the livestream!