Introduction. Prophecies and Protests ~ Signifiers Of Afrocentric Management Discourse

Since the early 1990s, dominant management discourse in South Africa has been contested by a locally emergent perspective that has come to be known as ‘African management’. It is doubtless still a rather marginal perspective, but one could argue it is a rather influential one. Over the years, African management has received quite some media attention.[i] Presently, a number of South African firms strongly sympathise with Afrocentric approaches, and actually make efforts to implement their principles. Eskom Holdings Limited is a case in point, which is contributing about 50 per cent of the total energy production in Africa with its approximately 32,000 employees, operating in 30 countries on the African continent. This ‘public enterprise’ that happens to be ‘Africa’s largest electricity utility’, has been undertaking bold initiatives to institutionalise its ‘African Business Leadership’ vision, illustrating a contemporary appropriation of ‘African management’ philosophy. Another example may be First National Bank (FNB).[ii] For several years, Mike Boon of Vulindlela Network has been actively involved in an organisational transformation initiative to change FNB’s organisational culture. Boon, who is the author of The African Way: The power of interactive leadership, is considered a renowned author on ‘African management’ issues (Boon 1996). Peet van der Walt, chief executive of FNB Delivery – also the man who approached Boon for this grand operation – stated that the initiative has met with overwhelming success (Sunday Times 28 April 2002). Eskom and FNB are two of the better-known illustrations, but several other organisations could be mentioned that are drawn towards to Afrocentric perspectives. Of course, we should not forget about the past experiences of Cashbuild, a wholesale company in building materials that was extensively described by Albert Koopman:

Since the early 1990s, dominant management discourse in South Africa has been contested by a locally emergent perspective that has come to be known as ‘African management’. It is doubtless still a rather marginal perspective, but one could argue it is a rather influential one. Over the years, African management has received quite some media attention.[i] Presently, a number of South African firms strongly sympathise with Afrocentric approaches, and actually make efforts to implement their principles. Eskom Holdings Limited is a case in point, which is contributing about 50 per cent of the total energy production in Africa with its approximately 32,000 employees, operating in 30 countries on the African continent. This ‘public enterprise’ that happens to be ‘Africa’s largest electricity utility’, has been undertaking bold initiatives to institutionalise its ‘African Business Leadership’ vision, illustrating a contemporary appropriation of ‘African management’ philosophy. Another example may be First National Bank (FNB).[ii] For several years, Mike Boon of Vulindlela Network has been actively involved in an organisational transformation initiative to change FNB’s organisational culture. Boon, who is the author of The African Way: The power of interactive leadership, is considered a renowned author on ‘African management’ issues (Boon 1996). Peet van der Walt, chief executive of FNB Delivery – also the man who approached Boon for this grand operation – stated that the initiative has met with overwhelming success (Sunday Times 28 April 2002). Eskom and FNB are two of the better-known illustrations, but several other organisations could be mentioned that are drawn towards to Afrocentric perspectives. Of course, we should not forget about the past experiences of Cashbuild, a wholesale company in building materials that was extensively described by Albert Koopman:

… we took up the challenge to change – really change – our business so that our people would see a different reality. And that would change their perception. […] We knew that our workforce was alienated from our system (they never understood it in the first place and never reaped the benefits from it either) and that we had to do a mighty good job to bring them into our business as ‘co-owners’. How else could they start believing in our business other than by reaping direct benefits from it? (Koopman; Nasser et al. 1987)

Overall, however, the dominant management and leadership style in South Africa is still mostly described as ‘western’. Usually, South African management is not only typified as ‘western’, but also as ‘North European’, ‘Eurocentric’, ‘British’, and ‘Anglo-Saxon’, or even as ‘American’.[iii] These terms are rarely well-defined, or differences clearly explained. There seems to be a consensus however, that British influence was amongst the strongest, and was assumed to have lasting effects. Textbooks and handbooks that are used in universities and business schools in South Africa are primarily written either by American or European authors, or else by local authors who write in a similar ‘mainstream’ tradition. An Afrocentric perspective could be a response to the felt need for ‘a contextualised approach’ to management and organisation in South Africa; at least that is how the issue was approached initially.

There is a body of literature on ‘African management’ (e.g. Boon 1996; Lessem and Nussbaum 1996; Mbigi 2006; 1997) and on management and organisation on the African continent (e.g. Blunt and Jones 1992; Jackson 2004; Kennedy 1988; Wohlgemuth, Carlsson et al. 1998). However, no book has yet brought together advocates of Afrocentric management approaches, practitioners, and academics, to analyse and contemplate on this fascinating and rapidly changing subject in a joint effort. Our focus is on the ‘African management’ discourse as a South African phenomenon, more precisely as an Africanist vision (or visions) on management and organisation. Read more

Prophecies And Protests ~ A Vision Of African Management And African Leadership: A Southern African Perspective

The purpose of this chapter is to explore the philosophical and cultural dimensions of African management and African leadership. The specific intention is to provide a vision of what African management has come to mean in my own life, as a person, raised in the Zezuru tribe (in Zimbabwe), schooled in Zimbabwe and, having built a career in Southern Africa, as a writer and practitioner/consultant who has applied African principles to management. Rather than purporting to be a descriptive study surveying the field of African management, this chapter takes a more phenomenological approach and is offered as an example of how African management has been applied and promoted during the past 15 years of my career. My hope is that it is seen as an attempt to give readers a deeper understanding of the cultural world which has influenced my life and work, and that readers, both African and non-African, will be inspired to envisage what African management could be. In my own view, African management principles, as I have learned to apply them, have the capacity to mobilise collective business transformations in a unique and effective way. The chapter attempts to illustrate some of the reasons for the effectiveness I have witnessed in the application of African management strategies. Rather than purporting to provide empirical research for these methods, these are descriptions and personal accounts of what they are and why they work.

The purpose of this chapter is to explore the philosophical and cultural dimensions of African management and African leadership. The specific intention is to provide a vision of what African management has come to mean in my own life, as a person, raised in the Zezuru tribe (in Zimbabwe), schooled in Zimbabwe and, having built a career in Southern Africa, as a writer and practitioner/consultant who has applied African principles to management. Rather than purporting to be a descriptive study surveying the field of African management, this chapter takes a more phenomenological approach and is offered as an example of how African management has been applied and promoted during the past 15 years of my career. My hope is that it is seen as an attempt to give readers a deeper understanding of the cultural world which has influenced my life and work, and that readers, both African and non-African, will be inspired to envisage what African management could be. In my own view, African management principles, as I have learned to apply them, have the capacity to mobilise collective business transformations in a unique and effective way. The chapter attempts to illustrate some of the reasons for the effectiveness I have witnessed in the application of African management strategies. Rather than purporting to provide empirical research for these methods, these are descriptions and personal accounts of what they are and why they work.

African management

African management has origins similar to modern management, in that its roots lie in African oral history and indigenous African religion. In 1993, People Dynamics, a South African personnel management magazine, published two essays, in which I articulated the African philosophy of ubuntu as a basis of effective human resources.[i] In the same year, Ronnie Lessem, Peter Christie and myself co-authored one of the earliest texts on African Management in South Africa (Christie, Lessem and Mbigi 1994). The book included an article on the application and adaptation of indigenous African religious concepts and practices to organisational transformation at Eastern Highlands Tea Estates in Zimbabwe. In fact it was due to my positive experiences as CEO of this company, which inspired me to abandon my career as a business director and devote my life to the articulation of African and cultural values and philosophy in management.

At Eastern Highlands I had successfully applied a variety of African cultural and religious practices and concepts to the organisational challenge of transformation management. These included: the adaptation of traditional rituals and ceremonies used in African religion; encouraging group singing and dancing to build morale, enhance production processes and engage large groups in collective strategy formulation, and the use of myths and story telling to build leadership and organisational cohesion. With contributions from other writers at the time, such as Reuel Khoza, Peter Christie and Ronnie Lessem, African management as a field of study and practice began to flourish as a discipline in South Africa, from the early 1990s. The African philosophy of ubuntu and its emphasis on interdependence and consensus provided its foundation.

Compared with western management theory and practice, African management is characterised by flatter structures which stress inclusion, interdependence, democracy and broad stakeholder participation. Rather than formal, uniform policies, African managers call for an emphasis on flexibility in relation to policies, which can be easily initiated, changed and transformed through a broad-based collective, mass-scale consensus and participation of many stakeholders. Instead of the tendency towards impersonal relationships in western management theory[ii] within an organisational context, African culture calls for highly personalised relationships. In African organisations, harnessing spiritual and social capital is an important management challenge. While there is hierarchy in African organisations, respect for hierarchy is emphasised in ceremonies. What drives organisations, more than official roles within a hierarchy, is the informal power that derives from natural social clusters, and consultation and negotiation depend largely on who owns the issue. Representation of all stakeholders and inclusion of all groups are given emphasis, so that African management is more about allowing multiple leadership roles and greater flexibility. Finally African management tends to prefer a web of interdependence of roles, relationships and competencies and is less concerned with structure and function than western management. Read more

Prophecies And Protests ~ Manufacturing Management Concepts: The Ubuntu Case

We are not born simply for ourselves, for our country and friends are both able to claim a share in us. People are born for the sake of other people in order that they can mutually benefit one another. We ought therefore to follow Nature’s lead and place the communes utilitates at the heart of our concerns (Cicero, De Officiis I, VII: 22).

We are not born simply for ourselves, for our country and friends are both able to claim a share in us. People are born for the sake of other people in order that they can mutually benefit one another. We ought therefore to follow Nature’s lead and place the communes utilitates at the heart of our concerns (Cicero, De Officiis I, VII: 22).

Introduction[i]

During the last decade ubuntu has been introduced as a new management concept in the South African popular management literature (Lascaris and Lipkin 1993; Mbigi and Maree 1995). ‘Even South Africa has made a contribution with the rise of something called ‘ubuntu management’, which tries to blend ideas with Africa traditions as tribal loyality’ (Micklethwait and Woodridge 1996: 57). Mangaliso (2001: 23) stresses that with the dismantling of apartheid in the 1990s, South Africa embarked on a course toward the stablishment of a democratic non-racial, non-sexist system of government.

‘With democratic processes now firmly in place, the spotlight has shifted to economic revitalization’. To support this revitalization, ubuntu became introduced as a new concept to improve the coordination of personnel in organisations. Mangaliso defines ubuntu as humaneness, ‘a pervasive spirit of caring and community, harmony and hospitality, respect and responsiveness that individuals and groups display for one another’. In that sense ubuntu demonstrates family resemblances with Cicero’s communes utilitates. By using the Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars model of the seven cultures of capitalism, Mangaliso reviews the competitive advantages of ubuntu.

One of the themes within the model focuses on language and communication. Mangaliso (2001: 26) points to the fact that

… traditional management training places greater emphasis on the efficiency of information transfer. Ideas must be translated quickly and accurately into words, the medium of the exchange must be appropriate, and the receiver must accurately understand the message. In the ubuntu context, however, the social effect on conversation is emphasized, with primacy given to establishing and reinforcing relationships. Unity and understanding among effected group members is valued above efficiency and accuracy of language.

To that end – Mangaliso notices – it is encouraging to see that after 1994 some white South African managers have begun to learn indigenous languages to better understand patterns of interactions and deal with personnel appropriately.

With this mastering of language(s) Mangaliso stresses an intriguing point, which requires further exploration. He creates a contrast between traditional management approaches (like Taylorism and Fordism) and ubuntu. Whereas the former only focus on formal language as a means to transfer information in an efficient way, the latter is based on conversation. This contrast reflects an interesting debate, which actually takes place in the management literature. There is the modernist perspective that conceives management knowledge as a predefined, reified object adopted by organisations. At the other hand there is an increasingly popular perspective conceiving management knowledge as constructed via processes of diffusion like conversation (Lervik and Lunnan 2004). In this respect it can be noticed that over the last decade there has been a significant increase in the study of language in organisations (Grant et al. 1998; Holman and Thorpe 2003; Moldoveanu 2002). The research being conducted in this area is meant to be potentially useful to managers. In that context the initiative of those white South African managers to learn other languages can be positioned as a way to become better experts while designing an approach which strengthens their capability to calculate rational solutions to problems by improved manipulation. This kind of approach is, however, still managerialist in the sense that it embraces the traditional view that managers get things done through the actions of others. A lot of management concepts that have been developed over the last fifty years indeed reinforce managerial interests instead of being focused on broader managerial practices. Read more

Prophecies And Protests ~ Ubuntu And Communalism In African Philosophy And Art

During my efforts to set up dialogues between Western and African philosophies, I have singled out quite a number of subjects on which such dialogues are useful and necessary. Recently I have stated in an essay that three themes in the African way of thought have become especially important for me:

During my efforts to set up dialogues between Western and African philosophies, I have singled out quite a number of subjects on which such dialogues are useful and necessary. Recently I have stated in an essay that three themes in the African way of thought have become especially important for me:

1.1 The basic concept of vital force, differing from the basic concept of being, which is prevalent in Western philosophy;

1.2. The prevailing role of the community, differing from the predominantly individualistic thinking in the West;

1.3. The belief in spirits, differing from the scientific and rationalistic way of thought, which is prevalent in Western philosophy (Kimmerle 2001: 5).

In these fields of philosophical thought there are contributions from African philosophers, which differ in a very characteristic way from Western thinking. Therefore in a dialogue on these themes a special enrichment of Western philosophy is possible. In the following text I want to clarify this possibility by concentrating on two notions, which have a specific meaning in the context of African philosophy. To discuss the notions of ubuntu and communalism means working out some important aspects of the second theme. The community spirit in African theory and practice is philosophically concentrated in notions such as ubuntu and communalism. But the concept of vital force, which is mentioned in the first theme, will play a certain role, too. We find the stem –ntu, which expresses the concept of vital force in many Bantu-languages, also in ubu–ntu. For a more detailed explanation of ubuntu, I will depend mainly on Mogobe B. Ramose’s book, which gives the most comprehensive explanation of the philosophical impact of this notion (Ramose 1999). The concept of communalism is explained in the context of the political philosophy of Leopold S. Senghor and other political leaders of African countries in the struggle for independence (Senghor 1964). A vehement critic of that theory is a Kenyan political scientist, V.G. Simiyu (Simiyu 1987). For a philosophical evaluation of this controversy I will refer to the articles and books of Maurice Tschiamalenga Ntumba, Joseph M. Nyasani, and Kwame Gyekye, dealing with the relation between person and community (Ntumba 1985 and 1988; Nyasani 1989; Gyekye 1989 and 1997).

Prophecies And Protests ~ The Scope For Arab And Islamic Influences On An Emerging ‘Afrocentric Management’

Abstract

Abstract

As there is in the global world of management a diversity of cultures and differing norms of behaviour so there is more than one ‘culture of management’: yet little attention has been paid to the ethical and philosophical bases of other paradigms than those with which we in Western business schools are familiar.

Where other philosophical and ethical systems are encountered, they are apt to be dismissed with the discourse of ‘traditionalism’ or ‘underdevelopment’, or stigmatized as inconsistent with the requirements of business efficiency. Many of these systems of ethics are embodied in cultural traditions that are, in origin, older than those of Western capitalism, yet in contemporary societies these may be evolving and transmuting radically, so it may be incorrect and unhelpful to see these economic systems as deviant cases or as unsuccessful attempts to reproduce Western modalities.

This paper draws on extensive research by the author and colleagues in the contemporary Arab world to identify the values under-pinning management in the Near East, Middle East and North Africa, and to analyze the opportunities for corresponding styles of leadership and management in certain regions of Africa. We suggest that these Islamic values may exert a growing influence on the emerging ‘Afro centric’ models in the Twenty-first century.

It is not claimed that these models of management are especially relevant for African conditions, but they may be and that is for scholars and business-people more familiar with Africa to determine. But it is to argue that they should be more widely understood and studied as a counter-weight to the pervading emphasis on the hegemonic models derived from the historically-specific legacies of the western and colonialist worlds.

In the first section we review the background to management in the region, in the second we review relevant research frameworks and findings, in the third section we focus on the defining elements of Islam as this relates to business, then we examine the impact of modernity and in the final section we discuss some future trends of especial import for emerging paradigms of management in Africa.

The Middle World

A well-known saying among the Bedouin of the Middle East goes as follows: ‘It is written: the path to power leads through the palace, the road to riches lies through the market, but the track to wisdom goes through the desert’. In the West and especially in business schools we tend to assume that we have the best maps to all of these three routes, and that they lead to places we already know about. So the paradigms of management on which we base our instruction in these academies are those with which we are already familiar. But we may be wrong in these assumptions for in fact we know very little about the Arab and Islamic worlds and their special ways of managing and their different approaches to money and wealth (Weir 1998). We also know rather little about ‘African’ styles and patterns of management; though hopefully this book will do something to redress that balance. Nonetheless what counts as ‘management’ in most of the pedagogic and research literature with which we are in principle familiar is in fact derived from what we know about Western management and business and from what we have learned about our varied attempts to introduce those models into other contexts. Thus we tend to problematise the issues that arise from these ventures at intellectual colonisation and to hold the Western models as ‘normal’. Read more

Prophecies And Protests ~ Unleashing The Synergistic Effects Of Ubuntu: Observations From South Africa

Abstract

Abstract

This paper argues that for the full economic revitalization of South Africa to take place, a critical step is to engage the synergistic effects of ubuntu or ‘humanness’, a philosophy which informs the thinking of a majority of South Africans. Ubuntu acknowledges that people are not just rational beings but that they are also social beings who possess emotions such as anxiety, hope, fear, anger, excitement and remorse. The position taken here is that openly recognising these human dimensions and accommodating them in everyday practice can unleash the synergistic effects of ubuntu. The paper gives examples of situations in which ubuntu manifests itself in the workplace, and provides lessons that can be learned from those situations. Among the advantages that can arise from harnessing the advantages of ubuntu are improvements in the corporate goals of employee satisfaction, productivity improvement, workplace harmony and, ultimately, the development of a vibrant economy that will further enhance the global competitiveness of the country.

Introduction

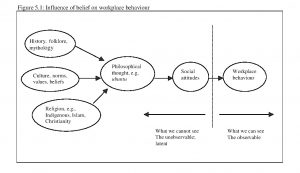

The dismantling of apartheid over a decade ago was a watershed event in the history of South Africa. The world watched as the country charted its course toward the establishment of a democratic, non-racial, non-sexist, system of government. With the democratic processes now firmly in place in the political arena, the spotlight has shifted to the economic revitalization of the country. But, as this paper will argue, sustained economic revitalization will not be possible until due regard is paid to the voices and aspirations of those who had been locked out of the democratic process for centuries. An important step in that direction is to understand the culture, values, norms and beliefs that predispose individuals to behave in certain ways. It is well known that individual behaviors and decisions are strongly influenced by prior socialization. Prior socialization itself is predicated on philosophical thought systems, which are strongly influenced by culture, norms, beliefs, history, folklore, and mythology; and religion (Hostede 1991; Roer-Strier and Rosenthal 2001; Thompson and Lufthans 1990). These relationships are shown schematically in Fig. 5.1.

The key to understanding the attitudes and behaviors of Africans in the workplace lies in learning about the philosophy of ubuntu. As a philosophical thought system, ubuntu shapes and informs the beliefs, values, and behaviors of a large majority of Africans in South Africa. Whether it is a critical issue that needs be interpreted or a problem that needs to be solved, ubuntu is invariably invoked as a barometer for good versus bad, right versus wrong, just versus unjust. Ubuntu can be viewed as an essential frame of reference for understanding African culture in South Africa (Brack, Hill, Edwards, Grootboom and Lassiter 2003; Lufthans, Van Wyk and Walumbwa 2004). In this essay we use Clifford Geertz’s (1973) understanding of culture as the web of understandings humans have spun. To Geertz (1973: 89), culture is an historically transmitted ‘pattern of meanings embodied in symbols, a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which [men] communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life’. We believe that culture is something that evolves over time in response to the conditions in which actors find themselves, whether social, economic, political, technological, ecological, and so on. This strongly implies that culture is not an abstraction, but a mutable social construction. The historical formation of culture thus becomes a source of primordial sentiments which are the ‘givens’ of a particular group because over time they carry a shared and understood meaning that is of absolute importance. As a component of culture, ubuntu evokes existential feelings akin to primordial sentiments (Shils 1957; Stewart 1987; Emminghaus, Kimmel and Stewart 1997). As will be seen in this chapter, these primordial sentiments provide reference points (respect, cooperation, solidarity, empathy, etc.) necessary for creating and maintaining stable identity and peaceful coexistence.[i] In this chapter we will give examples of situations in which ubuntu manifests itself in the workplace, and provide lessons that can be learned from those experiences. It will conclude by arguing that an understanding of ubuntu is the key to accomplishing the goals of employee satisfaction, productivity improvement, and ultimately workplace harmony.

Ubuntu

Over the centuries of their rule in South Africa, the colonial and later apartheid governments have perpetuated the fact that the African population of South Africa is composed of at least eleven ethnic groups, each with its own unique linguistic and characteristics and historic evolution. A superficial assessment of this incredible diversity would seem to preclude the identification of a common character among these ‘ethnic’ groups. But this would be overly naive, since it belies the underlying distinguishable pan-African character that binds African people, which is a product of its unique geographical, historical, cultural, and political experience (Sithole 1959; Antonio 2001). No other feature can more powerfully capture the essence of this pan-African character than ubuntu. The word ubuntu (botho) is a derivative from umuntu (in isiZulu), umntu (in isiXhosa) or motho (in Sotho), which means a person or a human being. The plural form in both isiZulu and isiXhosa is abantu or people. Literally, therefore, ubuntu means the state of being a person or human being. But when Africans use the term, it is associated with the kinder, gentler, and nobler qualities of human interaction. So for example, when someone performs an act of kindness, they are said to have ubuntu. Having ubuntu means being respectful, being generous and giving, preparing the extra plate of food just in case a stranger showed up, going the extra mile in helping those in need without expecting anything back from them. Loosely translated into English, ubuntu means humility or humaneness. As noted above, ubuntu runs deeper than that. It serves as the foundation for the basic African values that manifest themselves in the ways people think and behave toward each other and everyone else they encounter. It is lamentable that, until recently, these values have largely been ignored in the management discourse. For a long time the discussion of the concept of ubuntu has been limited to other fields in the social sciences such as theology (Sithole 1959; Setiloane 1986). It is only fairly recently that it found its way into the field of management (see See Khoza 1994; Senge, Kleiner, Roberts, Ross and Smith 1994; Makhudu 1993; Mangaliso 2001; Mbigi and Maree 1995; Prinsloo 2000). It is our contention that any effort to bolster economic vitality while, at the same time, creating a healthy work environment will necessarily have to begin with understanding and incorporating the fundamentals of ubuntu into management practices. The management practices referred to here include productivity improvement, leadership training, decision-making, and group dynamics. It is our hope that lessons from this paper will contribute toward a greater understanding of ubuntu, and thus provide useful knowledge for management practitioners and theorists with an interest in South Africa. The focus of the discussion in the paper will be on the various aspects of ubuntu as they relate to relationships to others, language, decision-making, attitude toward time, productivity and efficiency, leadership and age, and belief systems. These were selected since in the view of these authors they bring into stark relief the essential nature of ubuntu as described above. They will now be discussed in turn. Read more