South Korea’s Election Outcome: Opposition Party Triumphs, President Yoon Faces Diplomatic And Domestic Challenges

04-20-2024 ~ Opposition party wins in South Korea’s election, posing challenges for President Yoon’s governance and foreign relations, notably with China. Despite this, Yoon’s alignment with the U.S. and Japan is likely to continue, amid domestic concerns like inflation and medical strikes.

04-20-2024 ~ Opposition party wins in South Korea’s election, posing challenges for President Yoon’s governance and foreign relations, notably with China. Despite this, Yoon’s alignment with the U.S. and Japan is likely to continue, amid domestic concerns like inflation and medical strikes.

The liberal opposition party of South Korea has secured a sweeping majority in the nation’s general election, maintaining control of parliament. The Democratic Party (DP), led by Lee Jae-myung, attained 175 out of 300 seats in the National Assembly. This election is widely interpreted as a midterm assessment of President Yoon Suk Yeol, who still has three years remaining in his term. Following the results, the leader of his party, Han Dong-hoon, has stepped down, and Prime Minister Han Duck-soo has tendered his resignation.

Mr. Yoon and his People Power Party (PPP) have suffered a significant setback, grappling to advance their agenda within a legislature controlled by the DP. With the DP’s victory, it now has the leverage to expedite and advance legislative initiatives through parliament. The DP and PPP strategically utilize satellite parties to optimize their votes within South Korea’s electoral framework, wherein certain seats are allocated to smaller parties whose representation doesn’t proportionally match their overall support.

Satellite parties are smaller political entities that align themselves with larger, more established political parties. They often share similar ideologies or goals and cooperate strategically during elections to maximize their collective vote share.

Following his narrow defeat to Mr. Yoon in the 2022 presidential election, Lee Jae-myung is gearing up for another presidential bid. This election marks nearly two years since conservative President Yoon Suk Yeol secured victory in the 2022 presidential race by a razor-thin margin of 0.73 percent, the narrowest in South Korean history, prevailing over Lee.

At the national level, South Korea holds two major types of elections: presidential elections, where citizens directly elect the president for a single five-year term, and National Assembly elections, which determine the composition of the legislative body consisting of 300 members. These members serve a four-year term. Among them, 254 are elected through single-seat constituencies, while the remaining 46 members are selected through a proportional representation system. In the proportional representation system, voters vote for political parties rather than individual candidates, and the proportion of votes each party receives determines their seat allocation in the National Assembly.

In the 2024 South Korean general election, three main political parties competed for seats in the National Assembly. With 175 seats won, the Democratic Party became the largest party. The ruling People Power Party (PPP) secured 108 seats, while the Rebuilding Korea Party (RKP), led by former justice minister Cho Kuk, won 12 seats. Notably, the RKP obtained its seats solely through proportional representation, without fielding candidates for district positions. The overall voter turnout was 67 percent, marking the highest turnout in 32 years. Approximately 44 million people were eligible to vote in the National Assembly election, held on April 10, 2024.

Key Issues

The rising cost of living and inflation emerged as key concerns for voters, particularly the escalating prices of essential goods like vegetables. During the election campaign, President Yoon Suk-yeol’s visit to a supermarket brought attention to the issue, focusing on the price of green onions. Upon observing a bunch of green onions priced at 875 won ($0.65), he commented, “I’ve been to many markets, and this seems like a reasonable price.” However, media reports state that green onions typically now sell for three or four times that amount and local media reported that the store had discounted the vegetable ahead of Yoon’s visit.

In March 2024, South Korea’s annual inflation rate was at 3.1 percent. The primary contributors to this inflationary trend were the increased prices of fresh food and energy. In March, the prices of agricultural products surged by over 20 percent compared to the same month last year.

Another main concern in the election was the doctors’ strike. All medical interns and residents, actively practicing doctors, are rallying against Yoon’s proposition to boost the annual medical school admission quota by two-thirds to mitigate the doctor shortage. They contend that universities are ill-prepared to handle such a substantial surge in student intake, which could jeopardize forthcoming medical services.

Despite South Korea’s rapidly aging population and its low doctor-to-population ratio compared to other developed nations, attempts to increase medical school capacities have consistently encountered staunch resistance from incumbent doctors and medical students, resulting in significant political obstacles.

At first, Yoon’s proposal received public backing. However, increasing pressure for compromise arose as a result of the ongoing doctor strikes, causing numerous surgeries to be canceled and disrupting patient care.

Implications

The victory of the main opposition party indicates the continuation of strained relations between President Yoon and the legislative body. Since taking office, President Yoon has encountered consistent opposition to his domestic policies from the National Assembly, which is largely controlled by the opposition, holding approximately 60 percent of the seats. As of January 2024, only 29.2 percent of the bills presented to the National Assembly have been passed into law, a significant decrease from the 61.4 percent passage rate seen under the previous administration.

For months, President Yoon has struggled with low approval ratings, impeding his efforts to fulfill his promises of tax cuts, deregulation, and increased support for families in the world’s fastest-aging society.

The Yoon administration’s foreign policy has been characterized by a persistent alignment with the United States and Japan while distancing South Korea from China. Since assuming office, Yoon has been actively disrupting the relatively balanced diplomatic relations maintained by previous administrations and significantly straining China-South Korea relations.

Yoon’s alignment with the United States has also adversely affected the interests of the South Korean people. For instance, in the economic realm, South Korea has prioritized compliance with U.S. semiconductor export controls on China. Previously, South Korea had enjoyed close cooperation with China, resulting in a significant trade surplus. However, since joining the U.S.-proposed “Chip 4” alliance, South Korea has suffered considerable losses, while facing warnings from the U.S. against filling the void in the Chinese market. Yoon’s foreign policy has strained relations between China and South Korea, exacerbating trade and economic issues and eroding public support for Yoon.

When confronted with Japan’s discharge of nuclear-contaminated wastewater into the ocean, Yoon staged a symbolic act of eating seafood but failed to take substantive action in response to widespread public protests.

Nonetheless, it’s anticipated that South Korea’s foreign policy stance, including its trilateral cooperation with the United States and Japan, will remain relatively unchanged. The election outcomes are unlikely to exert significant influence on international affairs, and the president retains considerable autonomy to pursue his agenda. Yoon is expected to maintain a more assertive stance towards North Korea. His approach to North Korea sharply contrasts with that of the previous progressive administration, emphasizing negotiations and engagement.

By Pranjal Pandey

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Pranjal Pandey, a journalist and editor located in Delhi, has edited seven books covering a range of issues available at LeftWord. You can explore his journalistic contributions on NewsClick.in.

Source: Globetrotter

Perceptions Of Social Dominance And How To Change Them

04-19-2024 – It’s surprising that human infants as young as 10 months may be able to identify social rank. Research suggests that infants learn to distinguish who around them is dominant, using relative body size as a cue.

04-19-2024 – It’s surprising that human infants as young as 10 months may be able to identify social rank. Research suggests that infants learn to distinguish who around them is dominant, using relative body size as a cue.

Experiments by University of Oslo psychologist Lotte Thomsen indicate that infants may use the cue of body size to predict that a larger-sized object will prevail over a smaller-sized object in a controlled visual representation. And, a Yale University research team found that infants as young as three months seem to be able to recognize that voice pitch correlates with body size, with smaller organisms producing a higher pitch sound.

How Do We Know What Infants Think?

Researching and evaluating infant perceptions is complex. Experiments assessing infant reactions involve familiarizing them with an animated visual object, such as a colored block, and then varying its relationship with another similar block.

When the expected relationship is reversed, in what’s called a “violation of expectation,” researchers measure how long the infant gazes at the anomalous image, as compared to the length of its gaze on an expected image. The longer gaze at the unexpected image is interpreted as meaning that the infant recognizes something is not right.

For example, to assess the perception of dominance, Thomsen and an international team of researchers showed infants animations depicting a small and a large block moving toward each other, where one or the other would bow and give way to avoid a collision. In a series of experiments, they found that the infants gazed longer when the larger object yielded to the smaller one, suggesting that this was not what the infant expected.

This line of research suggests that by one year of age, infants may be able to recognize that size is related to strength and dominance, that the bigger size will prevail in a conflict situation, and that this holds for other conflict situations. These experiments conclude that knowledge of cues about perceiving social hierarchy develops very early in the human organism, and continues to develop through childhood and adolescence.

Other Species Do It Too

Studies comparing the hierarchical structure of human societies to those of other species suggest that “there may be no fundamental discontinuities between social structure in humans and animals.” Social hierarchy in animal groups is nearly ubiquitous: Non-human primates, insects, birds, and fish do it.

Social groups of non-human species form hierarchies to help protect the group from predators, reduce aggression within the group, find and allocate resources, and ensure that those at the top of the hierarchy can reproduce successfully—all of which is thought to contribute to the well-being of the group as a whole.

Social grooming is important in holding primate groups together by encouraging bonding. Studies show that primate grooming triggers the brain to release endorphins, which promote a sense of well-being and relaxationand at the same time create a sense of mutual trust. Grooming among primates can also be used as a form of conflict resolution and reconciliation. It’s suggested that the time-consuming grooming necessity limits the upper limit of primate group size to about 50.

Humans replicate the grooming effect of stimulating endorphins, Oxford University psychologist R. I. M. Dunbar suggests in a 2020 article, by creating a “form of grooming-at-a-distance,” which includes laughter, singing, dancing, storytelling, and communal eating and drinking. With humans as with primates, the endorphin-releasing practices allow the group members to know each other and predict the future behavior of group members. Read more

Nobody “Earns” A Billion Dollars. We Need A Wealth Tax

James K. Boyce – Photo by Matthew Cavanaugh

04-19-2024. Economist James K. Boyce analyzes new data on US disparities and frames environmental degradation as a class issue.

U.S. billionaires have seen their wealth nearly double since the Trump tax cuts took effect in 2017. In the meantime, the planet is getting hotter and the richest 1 percent of humanity accounts for more carbon emissions than the poorest 66 percent. Indeed, the interconnection between climate change and economic inequality has emerged as a central theme in serious economic analyses and a focal point of climate activism.

In the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows, progressive political economist James K. Boyce — who has just received the inaugural Global Inequality Research Award from Sciences Po and the World Inequality Lab for his groundbreaking work in the field of economic and environmental inequalities – explains the main causes behind the broad trend of rising inequality in the U.S. and globally, and how it is linked to environmental degradation.

However, as Boyce makes clear, environmental degradation does not impact everyone equally. Environmental degradation is a class issue as it disproportionately affects the poor, and it is the rich that benefit from environmentally harmful activities. Nonetheless, in spite of the challenges facing us in addressing climate change and inequality, there are economic instruments available to us that, if implemented, will create more equal societies and secure at the same time a sustainable future. This is especially critical as fossil fuel industry bosses are pulling out all stops to convince the world that it should “abandon the fantasy” of transitioning away from dirty energy.

Boyce is professor emeritus of economics and a senior fellow at the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is the author, among many other works, of Economics for People and the Planet: Inequality in the Era of Climate Change.

C.J. Polychroniou: I’d like to start by asking you to comment on the latest report by the nonprofit Americans for Tax Fairness showing that the combined wealth of U.S. billionaires has nearly doubled since 2017, hitting a record of $5.8 trillion. In light of this report, why does a wealth tax make sense in the effort to reduce inequality?

James K. Boyce: The first thing to say is that nobody “earns” a billion dollars. It’s simply not possible to make that much money by working for it, no matter how hard you work or how smart you are. So we have to ask, where does this enormous wealth come from?

In 2023 there were 735 billionaires in the U.S. (“a mere 735,” as Forbes put it). If their wealth rose by $2.9 trillion in the past six years, that means they each pocketed on average $39 billion — more than $6.5 billion apiece per year.

To which one might respond: WTF??! How did they do this?

There are three ways a person can accumulate enormous wealth. Winning the lottery is not one of them — the lottery is peanuts compared to the sums we’re talking about here. One way is by outright plunder: taking money and resources from other people, either by naked expropriation (like seizing control of lands and minerals) or monopolization (hence the U.S. term “robber barons”) or grand corruption. The second is by inheritance. If kids could choose their parents, we might say, ‘Well done, junior, you deserve to be rich because you made such a smart choice.’ But kids don’t choose their parents: the inheritors of great fortunes do nothing to deserve them. The third way is through the income spun off by wealth itself — profits, dividends, interest, rents, capital gains — what economists call “returns to capital” as opposed to returns to labor. The real problem is not that wealth grows over time. It’s that so few people have so much of it, while so many people have so little.

The toxic concentration of wealth in the U.S. and many other countries is not only an economic problem. It is a political problem, too. Disproportionate wealth translates into disproportionate political power, and this corrodes democracy. As inequality widens, the ultra-rich become more able and willing to elevate their own self-interest above the public interest. One obvious way they do so is by cutting their own taxes while increasing taxes (and cutting benefits) for everyone else.

Wealth taxes could be a powerful tool to address rampant inequality. The idea here is to tax not just income (the annual flows of money a person receives) but also accumulated wealth held as financial assets, real estate, and so on, above the threshold level that demarcates the ultra-rich. In practice, only a handful of countries have wealth taxes, and the U.S. is not one of them. Moreover, where wealth taxes do exist, their rates are typically modest — less than 2 percent, less than the average return to capital. This slows the rise of inequality but does not arrest it. Considerably higher rates would be needed to have a significant impact.

In addition to the wealth tax, there are other policies to combat toxic inequality. We need well-designed and well-enforced laws against plunder, including plunder in its latest guise: corporate smash-and-grab operations once called leveraged buyouts, that now go by the more innocuous-sounding name of “private equity.” We need laws against organized criminality that masquerades as legitimate business. We also need hefty inheritance taxes on outsized estates of more than, say, $10 million. And we need to remedy the perverse situation today in which billionaires pay lower rates of income tax than people who work for a living (Exhibit A is our tax-dodger-in-chief). Among other things, it is bizarre that unearned capital gains are taxed at a lower rate than hard-earned income. Read more

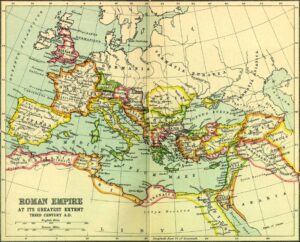

Property And Debt In Ancient Rome

Roman Empire – Source: en.m.wikipedia,org

04-16-2024 ~ The Roman concept of property is essentially creditor-oriented. As Rome’s power grew, practices quickly became predatory.

Traditional societies usually had restrictions to prevent self-support land from being alienated outside of the family or clan. By holding that the essence of private property is its ability to be sold or forfeited irreversibly, Roman law removed the archaic checks to foreclosure that prevented property from being concentrated in the hands of the few. This Roman concept of property is essentially creditor-oriented, and quickly became predatory.

Roman land tenure was based increasingly on the appropriation of conquered territory, which was declared public land, the ager publicus populi. The normal practice was to settle war veterans on it, but the wealthiest and most aggressive families grabbed such land for themselves in violation of early law.

Patricians Versus the Poor

The die was cast in 486 BC. After Rome defeated the neighboring Hernici, a Latin tribe, and took two-thirds of their land, the consul Spurius Cassius proposed Rome’s first agrarian law. It called for giving half the conquered territory back to the Latins and half to needy Romans, who were also to receive public land that patricians had occupied. But the patricians accused Cassius of “building up a power dangerous to liberty” by seeking popular support and “endangering the security” of their land appropriation. After his annual term was over he was charged with treason and killed. His house was burned to the ground to eradicate memory of his land proposal.

The fight over whether patricians or the needy poor would be the main recipients of public land dragged on for twelve years. In 474 the commoners’ tribune, Gnaeus Genucius, sought to bring the previous year’s consuls to trial for delaying the redistribution proposed by Cassius. He was blocked by that year’s two consuls, Lucius Furius and Gaius Manlius, who said that decrees of the Senate were not permanent law, “but measures designed to meet temporary needs and having validity for one year only.” The Senate could renege on any decree that had been passed.

A century later, in 384, M. Manlius Capitolinus, a former consul (in 392) was murdered for defending debtors by trying to use tribute from the Gauls and to sell public land to redeem their debts, and for accusing senators of embezzlement and urging them to use their takings to redeem debtors. It took a generation of turmoil and poverty for Rome to resolve matters. In 367 the Licinio-Sextian law limited personal landholdings to 500 iugera (125 hectares, under half a square mile). Indebted landholders were permitted to deduct interest payments from the principal and pay off the balance over three years instead of all at once.

Latifundia

Most wealth throughout history has been obtained from the public domain, and that is how Rome’s latifundia were created. The most fateful early land grab occurred after Carthage was defeated in 204 BC. Two years earlier, when Rome’s life and death struggle with Hannibal had depleted its treasury, the Senate had asked families to voluntarily contribute their jewelry or other precious belongings to help the war effort. Their gold and silver was melted down in the temple of Juno Moneta to strike the coins used to hire mercenaries.

Upon the return to peace the aristocrats depicted these contributions as having been loans, and convinced the Senate to pay their claims in three installments. The first was paid in 204, and a second in 202. As the third and final installment was coming due in 200, the former contributors pointed out that Rome needed to keep its money to continue fighting abroad but had much public land available. In lieu of cash payment they asked the Senate to offer them land within fifty miles of Rome, and to tax it at only a nominal rate. A precedent for such privatization had been set in 205 when Rome sold valuable land in the Campania to provide Scipio with money to invade Africa. Read more

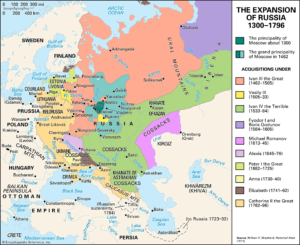

Where Did Vladimir Putin’s Dream Of A ‘Russian World’ Come From?

Source: Independent Media Institute

04-15-2024 ~ Russian President Vladimir Putin justified the 2022 invasion of Ukraine by asserting the existence of a singular “Russian world” that needs protection and reunification. He set aside the secular socialist ideological rationales that the Soviet Union used to justify its expansion favoring the Tsarist Russia, rooted in religion and culture. But the history of political orders in the northern European forest zone, which stretches back 1,200 years, is not one of a unified Russian world.

Instead, there were a series of competing orders with rival power centers in Kyiv, Vilnius, and Moscow as well as powerful nomadic steppe polities like those of the Khazar Khaganate, the Mongol Golden Horde, and the Crimean Khanate to the south. Only at the end of the 18th century would they all be forcibly annexed into a single state by Tsarist Russia’s Romanov dynasty. That unified state continued under its Soviet Union successor until it dissolved into 12 independent countries in 1991.

Ukraine and Lithuania in particular had been the centers of their own imperial polities with histories older than Russia itself and were instrumental in creating the Russian culture Putin is now so keen on defending. They achieved this in ways that did not require the protection of an autocrat.

Empires in The Forest Zone

The forest zone spanning the Dniester River in the west and the Volga River in the east historically constituted a vast (more than 2 million square kilometers) but sparsely populated region. It would become the home of three long-lived empires: Kievan Rus’ (862-1242), the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1251-1795), and the Grand Duchy (later Tsardom) of Muscovy (1283-1721). The surplus wealth that supported these empires came from international transit trade and the export of high-value furs, wax, honey, and slaves, often supplemented by raiding. After expanding beyond its forest zone home, Tsarist Russia declared itself the Russian Empire in 1721 during the reign of Peter the Great (1682-1725), but it took the rest of the century for it to gain control over its neighbors to the south and west, which was achieved during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762-1796).

States of any kind, let alone empires, were absent from the northern forest zone before the 9th century because it was then inhabited only by small and dispersed communities with little urbanization or political centralization. Engaged in subsistence farming, foraging, hunting, and animal husbandry, these communities interacted only with others like themselves or with foreign traders using its rivers to pass through the region. Dense forests and extensive marshlands presented serious obstacles to potential invaders, which were already few because the region had no precious metals to plunder or towns to occupy. This changed when the forest zone was drawn into the high-value commercial network that exchanged a flood of silver coins for furs and slaves, which were traded through a series of intermediaries. The demand for these goods and the silver to pay for them lay in the lands of the distant Islamic Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire, but it was the nomadic Khazar Khaganate (650-850), rulers of the entire steppe zone to the south, who dominated the trade routes. The Khazars exploited that position by projecting their power north into the forest zone where they imposed tribute payments in furs or silver on the communities residing there, creating a class of wealthy local leaders living in towns who were responsible for collecting the payments. They also established trading emporiums on the Volga River that attracted foreign merchants who paid a 10 percent transit tax on the goods they took in or out of the Khazar territory.

Kievan Rus’

The flow of silver resulting from the fur trade attracted the attention of Scandinavian maritime merchant/warrior groups known as the Varangians or Rus’, whose shallow draft boats were easily portaged from one watershed to another. Initially seeking only local trading opportunities, they established their political authority in the north but soon expanded southward through the Dnieper and Volga river systems to reach the Black and Caspian seas where they engaged in raiding and trading. The Varangians replaced the Khazars as the dominant power in the forest region in the 860s. By the 880s, they had moved their center south to Kyiv where they established an empire, Kievan Rus’, which encompassed 2 million square kilometers by the early 11th century. It was an empire that lasted almost four centuries and ended only after the Mongols conquered the entire region and destroyed Kyiv in 1240.

Although Kievan Rus’ is seen as the foundation of later Russian culture, it did not assume its classic form until a century and a half after it was established when Vladimir the Great (r. 980-1015), a pagan polytheist, converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 988 and made it the state religion after marrying a Byzantine princess. He was also responsible for turning Kyiv into a true city with a population of around 40,000 people, erecting Byzantine-style churches there and supporting trade. It was a multiethnic state that developed its own common culture by drawing on a variety of sources. Eastern Orthodox Christianity brought with it a tradition of literacy and the Cyrillic alphabet, a hierarchical clerical establishment, and a Byzantine tradition of governance where state authority was based on laws and institutions. Rus’ rulers also respected the authority of existing Slavic political institutions at the local level that included decision-making councils in towns and regions (veche), Indigenous local rulers (kniaz), and a class of aristocratic military commanders (voevoda). Although only the direct descendants of the Rus’ founder Rurik could hold the top position of the grand prince and other high ranks, this ruling lineage intermarried with its Slavic subjects (Vladimir’s mother was one of the offsprings of this kind of intermarriage), and eventually adopted their language.

Perhaps most significantly, Kievan grand princes did not wield absolute power. After the empire reached its zenith under Vladimir and his son Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1016–1054), constant wars of succession among the Rurikid elite weakened the central government to such an extent that by the mid-12th century it had devolved into a looser federation of autonomous regional polities (with Kyiv, Novgorod, and Suzdalia being the most prominent) whose leaders agreed among themselves on who would become the grand prince. The government survived because it was a jellyfish-like state that absorbed enough resources to sustain itself without requiring either a strong imperial center or autocratic leadership, and where no single part was critical to the survival of the whole.

Lacking a brain, jellyfish depend on a distributed neural network composed of integrated nodes that together create a highly responsive nervous system. As a result, jellyfish can survive the loss of body parts and regenerate them quickly. Similarly, Kiev and its grand prince was only the biggest node in a system of nodes rather than an exclusive one. And because jellyfish regeneration is designed to restore damaged symmetry rather than simply replace the lost parts, a jellyfish cut in half becomes two new jellyfish as each half regenerates what is missing. Following this pattern as well, two rival empires eventually emerged in the lands of the old Kievan Rus’ after the Mongol occupation finally ended: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the west and the Grand Duchy of Muscovy in the east. Read more

A Class Analysis Of The Trump-Biden Rerun

Richard D. Wolff

04-15-2024 ~ By “class system” we mean the basic workplace organizations—the human relationships or “social relations”—that accomplish the production and distribution of goods and services. Some examples include the master/slave, communal village, and lord/serf organizations. Another example, the distinctive capitalist class system, entails the employer/employee organization. In the United States and in much of the world, it is now the dominant class system. Employers—a tiny minority of the population—direct and control the enterprises and employees that produce and distribute goods and services. Employers buy the labor power of employees—the population’s vast majority—and set it to work in their enterprises. Each enterprise’s output belongs to its employer who decides whether to sell it, sets the price, and receives and distributes the resulting revenue.

In the United States, the employee class is badly split ideologically and politically. Most employees have probably stayed connected—with declining enthusiasm or commitment—to the Democratic Party. A sizable and growing minority within the class has some hope in Trump. Many have lost interest and participated less in electoral politics. Perhaps the most splintered are various “progressive” or “left” employees: some in the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, some in various socialist, Green, independent, and related small parties, and some even drawn hesitatingly to Trump. Left-leaning employees were perhaps more likely to join and activate social movements (ecological, anti-racist, anti-sexist, and anti-war) rather than electoral campaigns.

The U.S. employee class broadly feels victimized by the last half-century’s neoliberal globalization. Waves of manufacturing (and also service) job exports, coupled with waves of automation (computers, robots, and now artificial intelligence), have mostly brought that class bad news. Loss of jobs, income, and job security, diminished future work prospects, and reduced social standing are chief among them. In contrast, the extraordinary profits that drove employers’ export and technology decisions accrued to them. Resulting redistributions of wealth and income likewise favored employers. Employees increasingly watched and felt a parallel social redistribution of political power and cultural riches moving beyond their reach.

Employees’ class feelings were well grounded in U.S. history. The post-1945 development of U.S. capitalism smashed the extraordinary employee class unity that had been formed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. After the 1929 economic crash and the 1932 election, a reform-minded “New Deal” coalition of labor union leaders and strong socialist and communist parties gathered supportively around the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration that governed until 1945. That coalition won huge, historically unprecedented gains for the employee class including Social Security, unemployment compensation, the first federal minimum wage, and a large public jobs program. It built an immense following for the Democratic Party in the employee class.

As World War II ended in 1945, every other major capitalist economy (the UK, Germany, Japan, France, and Russia) was badly damaged. In sharp contrast, the war had strengthened U.S. capitalism. It reconstructed global capitalism and centered it around U.S. exports, capital investments, and the dollar as world currency. A new, distinctly American empire emerged, stressing informal imperialism, or “neo-colonialism,” against the formal, older imperialisms of Europe and Japan. The United States secured its new empire with an unprecedented global military program and presence. Private investment plus government spending on both the military and popular public services marked a transition from the Depression and war (with its rationing of consumer goods) to a dramatically different relative prosperity from the later 1940s to the 1970s.

Cold War ideology clothed post-1945 policies at home and abroad. Thus the government’s mission globally was to spread democracy and defeat godless socialism. That mission justified both increasingly heavy military spending and McCarthyism’s effective destruction of socialist, communist, and labor organizations. The Cold War atmosphere facilitated undoing and then reversing the Great Depression’s leftward surge of U.S. politics. Purging the left within unions plus the relentless demonization of left parties and social movements as foreign-based communist projects split the New Deal coalition. It separated left organizations from social movements and both of them from the employee class as a whole. Read more