Carbon Farming: A Sustainable Agriculture Technique That Keeps Soil Healthy And Combats Climate Change

01-10-2024 ~ How one North Dakota farmer saved his farm and livelihood using carbon-friendly farming methods.

01-10-2024 ~ How one North Dakota farmer saved his farm and livelihood using carbon-friendly farming methods.

What if there were a way to safely pull billions of tons of carbon out of the atmosphere to substantially reduce or even eliminate global warming?

What if this approach costs relatively little and could be used around the world?

What if it also put billions of dollars in cash into the hands of countless working Americans and people worldwide?

What if it even slashed fossil fuel consumption and made the world more resilient to climate stress?

Well, it turns out there is a system that can do all that. It’s called carbon farming, and it just might be key to restabilizing the climate. In the process, it can revitalize rural economies while also producing healthier, more nutritious crops. And amazingly, it’s also low-cost, low-tech, and low-risk.

The carbon farmer works with simple inputs: land, seed, compost, moisture, sometimes animals and manure, and sometimes specially selected microorganisms that speed a depleted soil’s return to health.

Carbon farming doesn’t pull land out of production or abuse natural ecosystems. It’s a “down-to-earth” solution to global warming that employs nature’s omnipresent carbon cycle, which constantly shuttles carbon molecules into and out of the atmosphere, soil, fresh water, and ocean. Yet carbon farming is still neither widely known nor widely practiced.

A School of Hard Knocks

In well-worn jeans and a plaid shirt, Gabe Brown looks like the North Dakota farmer-rancher he is. But if you were to assume that Brown practices typical U.S. production agriculture, you would be wrong. Brown has an iron will, a deep religious faith, a tremendous capacity for hard work, and “a calling” to bring hope to struggling farmers and ranchers while providing healthful food to consumers. Unlike most farmers, though, he’s not as concerned with yields per acre or dollars per pound as he is with soil health.

How soil became “top of mind” for Brown—and how he became a rock star of regenerative agriculture—is a tale of good tidings for the climate, the planet, and agriculture in the United States.

Early in his farming career, Brown endured modern-day trials of Job. In 1995, he wasn’t much different from many farmers he knew: a young man with a new family, a struggling farm, and a sizable operating loan to service. That year, a hailstorm wiped out 1,200 acres of his spring wheat the day before he was to start harvesting it. Because hail had been uncommon and mild during the previous 35 years, Brown had no hail insurance and was financially devastated.

The bank stuck with him, though, and loaned him more money—but, once again, the following year, hail destroyed his entire crop. At that point, the bank refused to provide a similar new loan.

Brown had to figure out how to ranch and farm without all the expensive chemical fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and genetically modified (GMO) seeds on which neighboring farmers and ranchers depended, and which he now had no money to purchase.

In those days, no one baled the grass in the roadside ditches into hay for cattle because of the garbage and rocks found there. “It was a pain to do,” Brown recalled. But his ranch was relatively small, and he could no longer afford to buy forage for his cattle. So, he went from neighbor to neighbor and asked if he could put the hay in their ditches.

“They just laughed and said, ‘Sure.’” “I would mow it and rake it and bale it. Then I’d carry those small square bales out of that ditch [and] onto the road. At night, my wife would drive with the kids in the car seats with a flatbed trailer behind, and I’d throw those bales onto that trailer one at a time. They probably averaged about 70 or 75 pounds, and I remember years we did 7,000 of them. … That’s a lot of steps up and down a road ditch.”

The next year, 1997, was extremely dry. Brown and his wife Shelly were just able to scrape enough feed together to keep the cattle, but once again, he had no crop income. “So, you just keep digging a bigger hole because we had land payments to make,” he explained.

The next June, another hailstorm cost Brown 80 percent of his crop.

Those four years, Brown said, “were hell to go through. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody, but in the end, it was the best thing that could have happened because it forced me to change my mindset. … I realized, ‘I have to look at my whole operation… from the eyes of nature and how nature functions.’”

Refocusing on the Synergies of Nature

During the years of hail and drought, Brown had often wondered how the 2,000 acres of unplowed native prairie on his land could grow so much forage naturally every year without synthetic inputs. It always had live roots, was always protected by vegetation that sealed in the moisture, and was extraordinarily rich in species.

To figure this out, Brown went to his local public library. There, he read the journals Thomas Jefferson had kept about agricultural practices on his plantation at Monticello, Virginia, where Jefferson planted turnips and vetches to improve degraded soil. Brown also read the journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who had wintered at native Mandan villages in North Dakota—just north of Brown’s ranch—in the early 19th century. The Mandans planted “the three sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—along with tobacco. They were focusing on the synergies of nature, said Brown. They got a legume, a grass, and the squash plant “all working in harmony to benefit each other.” He took note.

Brown also noticed that when the third hailstorm pounded his crops onto the ground, it armored his thirsty soil, sealing in its moisture against drought. This was important because his ranch has no irrigation and gets only 10 to 12 inches of rainfall a year, plus another 5 inches of moisture from melted snow. (It snows there every month except July.)

Informed by his new knowledge of Mandan agriculture, Brown decided to try planting legumes and grass, cover crops that would thrive synergistically through the residue of the hail-killed crops. He intended to raise feed for his livestock and add organic matter to the soil. Then, not even having money to buy the twine to bale hay, Brown simply let his livestock graze off the cover crops. The livestock got a free meal, and their manure enriched the soil. “That started the act of livestock integration on cropland.”

Carbon-Friendly Agriculture

Through his efforts to survive and keep his farm, Brown gained crucial insights into how ecosystems function and the importance of livestock to maintaining a healthy soil ecosystem. Surmounting the challenges this presented forced him to create a new, “carbon-friendly” agriculture that was as economical, as creative, and unconventional.

At a time when many family farms were succumbing to competition from industrial agriculture, Brown was able to avert bankruptcy by throwing out the prevailing business model. Instead of the soil-depleting, additive-heavy, financially draining agricultural practices he had learned in vocational school, his farming techniques mimic nature, heeding soil biology and integrating profitable enterprises in an agrarian ecosystem in which little is wasted; the byproducts of one operation are cleverly used as the inputs or feedstock of another.

As a result, the more than 130 different products sold by Brown’s Ranch include organic, grass-fed beef and lamb, pastured pork and pigs, poultry, honey, fruit, and heirloom vegetables in season, as well as border collies. “Don’t tell me there’s no money in production agriculture!” he said. “There’s a myriad of opportunities.”

These days, instead of baling grass in ditches at night, Gabe Brown is on the road most of the year to consult and lead regenerative agriculture workshops through the nonprofit Soil Health Academy, where he is a partner. “I really believe that my purpose is to give people hope. … By that, I mean farmers and ranchers and now, more so, consumers. … We’re trying to regenerate everything, including climate.”

What Makes Soil Ecosystems ‘Tick’

To understand what Gabe Brown is up to, one has to understand how soil ecosystems operate: they run on carbon, the same way fuel powers an engine. Carbon-rich organic matter gives rich, fertile soils their dark color and clumpy texture and nourishes soil organisms and plants. Carbon-poor soil is less able to support life, producing lower crop yields, less forage, and less biodiversity. Soil health is like a magic elixir for climate health.

Brown’s new approach to farming was not initially aimed at mitigating climate change. He simply noticed that the cover crops he grew, when his fields otherwise would have been fallow, significantly raised the soil’s water-holding ability and put more live roots into it year-round, as on the native prairie; when those cover crops died, their roots decomposed and increased the soil’s organic matter content, nourishing other plants and soil organisms.

So, the organic matter Brown added to nourish his crops and livestock also had the unsought benefit of boosting the soil’s carbon concentration. (Organic matter is more than 50 percent carbon.) Even in harsh, dry North Dakota—where it’s sometimes -40 degrees Fahrenheit in winter—Brown’s agricultural techniques have captured vast amounts of valuable carbon. And that carbon, removed from the air and packed away in the soil, provides climate benefits.

Sequestering Carbon in the Soil

Brown’s Ranch was the subject of a soil survey operation designed by John M. Norman, an environmental biophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Norman analyzed the carbon and nitrogen in the ranch’s top 4 feet of soil. An early measurement he made in 2017 indicated that those horizons contained an extraordinary amount of carbon per acre (92 tons), but the preliminary estimate was never confirmed, despite some follow-up measurements in 2018 and 2019, due to the project’s premature termination. “The amount of carbon he’s sequestered in this soil is staggering,” Norman told me at the time. Even digging 4 feet below the surface wasn’t deep enough for Norman to record all the extra carbon.

Moreover, he said, “The deeper you bury the carbon, the longer it’s going to be in there.” That’s important for climate stability because if the carbon moves back into the air right away, it hasn’t been purged from the atmosphere for the long term. “[Gabe] built a remarkable soil in a couple of decades. … A wise farmer,” Norman concluded, “can grow soil a lot faster than Mother Nature.”

To further increase his soil’s organic matter, Brown nowadays inoculates his seeds with mycorrhizal fungi, and he plants a diverse mix of cover crops to keep the soil from overheating in the summer as the plants capture carbon from the air. Mycorrhizal fungi form a relationship with the roots of vascular plants and are critically important to the development of soil structure, fertility, and water-holding capacity; they also aid plants in using soil nutrients and resisting disease. By promoting plant growth and health, they help increase soil organic matter. “Nature is more collaborative than competitive,” Brown believes.

‘Mob-Grazing’ Pasture

Ultimately, Brown’s cover crops are incorporated into the soil after frost kill and decomposition or when Brown “mob-grazes” a pasture. That’s when cattle trample much of the forage into the soil, protecting it against wind and water erosion and helping it to insulate the ground from temperature extremes, thereby improving warm-weather water retention.

“The hotter it gets, the less water is available for plant growth,” Brown said. “At 70 degrees, 100 percent of the water is available for plant growth. At 100 degrees, only 15 percent is used for growth, and 85 percent is used for evaporation. At 130 degrees, 100 percent of water evaporates; at 140 degrees, soil bacteria die.”

“[Soil] structure is built by a living system of microorganisms—little animals and the roots of the plants,” Norman said. “They basically make a house for themselves and maintain that structure under a condition that’s high yield for the whole system.”

Conventional Versus Regenerative Agriculture

Conventional farmers are addicted to fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides. They see nature as more competitive than cooperative, so they try to remove or poison anything they see competing with their crops—thereby killing beneficial insects and soil life, including the helpful fungi. In addition, conventional farmers often leave the ground bare in the spring, allowing the soil to erode under rushing snowmelt water and pounding rains that can seal its surface, increasing runoff and decreasing water storage.

By contrast, in Brown’s regenerative agricultural system, plant residues are left on the ground to decompose, and tiny organisms come up to the soil surface. “They increase the infiltration rate by a huge factor,” Norman said. This is important not only for allowing adequate moisture to soak in to carry plants through dry spells but also for farmers and ranchers trying to adapt to climate change.

As the climate gets warmer and the frequency and severity of flooding increases, permeable soil is more important than ever to absorb the heavier rainfall. “Gabe Brown’s soil can take a foot of water in an hour with no runoff,” Norman reported. “That’s unheard of in a conventionally tilled agricultural soil.”

By John J. Berger

Author Bio:

John J. Berger is an environmental science and policy specialist, prize-winning author, and journalist. His latest book is Solving the Climate Crisis: Frontlines Reports from the Race to Save the Earth (Seven Stories Press, 2023). He is a contributor to the Observatory.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This adapted excerpt is from Solving the Climate Crisis: Frontline Reports From the Race to Save the Earth © 2023 by John J. Berger and is licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by permission of Seven Stories Press. It was adapted and produced for the web by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

What Is To Be Done?

Richard D. Wolff

01-10-2024 ~ In 1863, the Russian social critic, Nikolay Chernyshevsky, published a novel entitled “What Is to Be Done?” Its story revolves around a central heroine, Vera Pavlovna, and her four dreams. It brilliantly intertwines her personal life and the social turmoil of Russia’s transition at the time from feudalism to capitalism. Chernyshevsky, a revolutionary imprisoned by the Czarist government, wrote a novel that was nothing less than a pioneering work of socialist feminism. In it, he also passionately appealed for an urban, industrial economy based on worker cooperatives, a modern and transformed version of Russia’s earlier agrarian communes. An appreciative Lenin entitled one of his most important political pamphlets, published in 1902, “What Is to Be Done?”

Two decades later, after the Soviet revolution defeated foreign invaders and domestic enemies in a long civil war, Lenin returned to the theme of worker cooperatives. In Soviet circumstances, much changed from Chernyshevsky’s Russia, Lenin argued forcefully for the USSR’s activists to recognize the enormous importance of building, spreading, and respecting cooperatives as key to Soviet socialism’s future. Worker coops, he argued, answered the burning political question among activists then: what is to be done? Here I want to adapt and apply Lenin’s argument to today’s social conditions that are raising that same question even more urgently.

Today’s capitalism is global—the basic economic structure of the world economy features its core employer-employee model. The “relations of production” inside enterprises (factories, offices, and stores) position a small minority of workplace participants as employers. They make all the basic “business decisions” about what, how, and where to produce and what to do with the product (and revenue when they sell it). They alone make all those decisions. Employees, the majority of workplace participants, are excluded from those decisions.

Capitalism today is also globally divided into two major blocs: one old and one new. The old is allied with the United States. Besides being older, the G7 is now the smaller of the two blocs, having shrunk in relative global importance over recent decades. It includes the UK, Germany, France, Italy, Canada, and Japan as well as the United States. The now fast-rising newer bloc, the BRICS, first included Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Recently, it invited six new member states to join, as of January 2024: Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, and Argentina. Since 2020, the BRICS’ total GDP exceeded that of the G7, and that gap between them keeps growing.

The G7’s “mature capitalisms” all survived and grew because workers accepted the employer-employee organization of workplaces. Amid and despite the G7 nations’ endless ideological celebrations of democracy, workers accepted the total absence of democracy inside capitalist enterprises. With some exceptions and resistance, it became routine common sense that representative democracy somehow belonged in residential communities but not in the communities at work. Inside capitalist enterprises, autocracy was the norm. Employers ruled employees but were not democratically accountable to them. Employers in each capitalist enterprise enriched a select circle by delivering portions of the revenue to themselves, to owners of the enterprise, and to a few top executives. That select circle wielded extraordinary political and cultural influence. It replicated the absence of democracy inside its enterprises by keeping the democracy outside them merely formal. Governments in capitalism were typically shaped by that select circle’s paid lobbyists, campaign donations, and paid mass-media productions. In modern capitalism, the kings and queens banished in earlier centuries reappeared, altered, and relocated, as CEOs inside ever larger capitalist enterprises dominating whole societies.

Employees’ actual or anticipated opposition to democracy’s exclusion inside workplaces has always haunted capitalism. One major way employers can deflect such opposition is by narrowly defining their obligation to employees in terms of wages paid to enable consumption. Wages adequate for consumption became the necessary and explicitly sufficient compensatory reward for work. Implicitly, they likewise became the employees’ compensation for the absence of democracy within the workplace. Rising levels of employee consumption signaled a “successful” capitalism. In stark contrast, rising democracy inside the workplace never became a comparable standard for evaluating the system.

Making consumption the point and purpose of work contributed to a social overvaluation of consumption per se. Advertising contributed to that overvaluation too. Modern capitalist society added “consumerism” to its catalog of moral failings. Clerics thus routinely caution us not to lose sight of spiritual values in rushing to consume (of course, those spiritual values rarely include democratic rights inside workplaces).

Confronted and outcompeted by China and the BRICS, G7’s declining empires and economies now risk that mass consumption will increasingly be constrained. In declining empires, the rich and powerful preserve their wealth and privileges while offloading the costs of decline onto the mass of employees. Automating jobs, exporting them to lower-wage regions, importing cheap immigrant labor, and mass campaigns against taxes are the tried-and-true mechanisms to accomplish that offloading.

Such “austerities” are now in full swing nearly everywhere. They explain a good part of the mass working-class anger and bitterness in the older (G7-type) capitalisms expressed in gestures against social “elites.” Given capitalism’s long favoritism shown to its right-wing versus its left-wing critics, it should surprise no one that the anger and bitterness first take right-wing forms (Trump, Boris Johnson, Wilders, Alternative for Germany, and Meloni).

The political temptation for the left will be to focus again as it did in the past on demanding rising consumption now that a declining capitalism undermines it. Capitalism promised a rising consumption that it now fails to deliver. Fair enough, but that is not enough. Often in the past, capitalism was able to deliver rising real wages and workers’ living standards. And it may yet again. Indeed, China is now delivering just that.

The clear lesson is that the left needs a new and different answer to the question of what is to be done. Its criticism must effectively criticize and oppose capitalism when and where it is delivering rising wages and likewise when and where it is not.

Now is the time to expose and attack capitalism’s deprivation of democracy in the workplace and the resulting social ills (inequalities, instabilities, and merely formal political democracy). Workers’ goals never needed to be and should never have been limited to raising wages, important as that was and is. Those goals can and should include a demand for full democracy inside the workplace. Otherwise, whatever reforms and gains workers’ struggles achieve can subsequently be undone (as happened to the New Deal in the United States and social democracy in many other countries). Workers have had to learn that only democratized workplaces can secure the reforms workers win. What is to be done in the old, declining centers of capitalism is for class struggles to include the democratization of enterprises. A transition toward economies grounded on worker-cooperative enterprises is the strategic target.

In the new, ascending capitalisms in the world, the BRICS, a different logic leads again toward worker cooperatives as a focal goal for socialist politics and organizing. Among the BRICS, the same employer-employee model organizes factories, offices, and stores. Unlike the G7, the employers are relatively more often not private. Rather, some employers run privately owned enterprises, while others are state officials who operate enterprises owned by the state. In the People’s Republic of China, where roughly half of enterprises are private and half public, nearly all have adopted the employer-employee organizational model.

Where the state takes a large, major, or commanding role in economic development and especially where one or another socialist ideology accompanies and justifies that role, a turn toward a focus on worker cooperatives is now timely. It will attract many in those countries as socialism’s necessary next step. The “development” or socialism accomplished there—macro-level changes already achieved (via decolonization struggles and revolutions)—are celebrated but also widely understood as insufficient. Bigger social goals and changes motivated those struggles and revolutions. Democratizing enterprises takes “development” to a whole new level reaching toward those goals.

There is yet another source of the answer that now responds to the question: what is to be done? The qualities of democracy that have been achieved within the G7, the BRICS, or most other countries, to date have been more formal than substantive. Where elections of representatives occur, the influences of wealth and income inequalities, the social power wielded by CEOs, and their controls over mass media render democracy more symbolic than real. Many people know it; still more feel it. Extending democracy into the economy and specifically into the internal organization of enterprises represents a major step in moving political democracy beyond merely formal and symbolic to substantive and real. And much the same applies to moving socialism beyond its earlier forms.

The old cry to workers of the world to unify—“You have nothing to lose but your chains”—was an early, partial answer to the question: What is to be done? After a century and a half of development and socialisms, we can now provide a much fuller and more specific answer to that question. To get beyond capitalism’s core—the production relations of employer versus employee—we need explicitly to replace those relations with a democratized workplace, to substitute workers’ self-directed cooperatives for hierarchical capitalist business.

By Richard D. Wolff

Author Bio:

Richard D. Wolff is professor of economics emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a visiting professor in the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University, in New York. Wolff’s weekly show, “Economic Update,” is syndicated by more than 100 radio stations and goes to 55 million TV receivers via Free Speech TV. His three recent books with Democracy at Work are The Sickness Is the System: When Capitalism Fails to Save Us From Pandemics or Itself, Understanding Socialism, and Understanding Marxism, the latter of which is now available in a newly released 2021 hardcover edition with a new introduction by the author.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

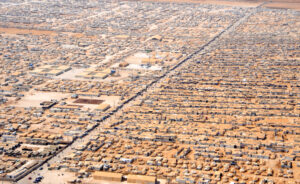

The Problem Of Refugee Camps In The Middle East And North Africa

Za’atari refugee camp – Jordan

Photo: en.wikipedia.org

01-08-2024 ~ In 2024, 12 percent of “forcibly displaced and stateless people” are expected to be from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, said the United Nations. This displacement will be caused due to war, humanitarian crises, and environmental catastrophes. The number’s recent causes are the civil war in Sudan and the fallout from natural disasters in Turkey, Syria, Morocco, and Libya. This percentage does not include the millions of people in Palestine who have been displaced since 1948.

At Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan, where 20-year-old pregnant Syrian woman Souad lives, children make up 50 percent of the camp’s population of more than 80,000.

“Raising a child in the camp is difficult. There’s limited access to essential resources such as clothing and baby milk formula,” Souad told the Wilson Center, a U.S.-based policy think tank in June 2023.

For a short while in 2013, Za’atari was the fourth-largest city in Jordan and was host to more than 200,000 people from Syria at the time. The population of the 11-year-old refugee camp has since decreased, but with no sign of an end to the conflict in neighboring Syria, Za’atari remains the biggest refugee camp in the Middle East and one of the largest in the world, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (The vast majority of refugees don’t live in formal camps.)

The UNHCR stated that an estimated 131 million people are projected to be displaced around the world in 2024.

Of the total 131 million people who are projected to be displaced, 63 million are expected to be internally displaced and another 57 million will be refugees or those who are externally displaced, said the UNHCR. As with Za’atari, women and children will make up the vast majority of those who have been displaced.

In 2022, more than three-quarters of the refugees were hosted in low- and middle-income countries, with Turkey leading the way in sheer numbers at 3.6 million followed by Iran at 3.4 million. Meanwhile, “Lebanon hosts the largest number of refugees per capita (one in eight), followed by Jordan (one in fourteen),” stated the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The majority of the refugees in the MENA region are from Syria, where the civil war began in 2011 and continues unabated. More than 5.3 million refugees from Syria are in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and North Africa. Germany also hosts roughly 560,000 Syrian refugees, the most in Europe.

This does not include about 6.8 million internally displaced persons who remain in Syria. About three-quarters of those under the purview of UNHCR in the MENA region were internally displaced, including millions from Yemen’s and Syria’s civil wars.

Za’atari, which features a bustling business thoroughfare known as the Sham Elysees (a play on the Arabic word for Syria and the Parisian avenue Champs-Élysées ), is often highlighted for the “entrepreneurial” spirit of the refugees. But 18-year-old Asia Amari, a resident of the camp, said in 2016 to CNN, “We are not living here, it’s just an existence.”

A visit to another refugee camp for Syrians in Jordan, Azraq, reveals a very different story than the one about a thriving bazaar. Designed as a model camp, Azraq has been characterized as “a heavily controlled, miserable, and half-empty enclosure of symmetrical districts that restricts economic activity, movement, and self-expression.” Refugees have characterized it as an “outdoor prison” and outside observers have called it a “dystopian nightmare.”

Meanwhile, nearly 6 million multigenerational Palestinian refugees fall under the mandate of a different UN body. About 1.5 million Palestinian refugees live in refugee camps in the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, as well as smaller numbers reside in other MENA countries.

According to the United Nations Relief and Work Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), which oversees the camps for Palestinians, “Socioeconomic conditions in the camps are generally poor, with high population density, cramped living conditions, and inadequate basic infrastructure such as roads and sewers.”

For example, the nearly 488,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are stateless and “have very limited access to public health care, education, or the formal economy,” according to the think tank Migration Policy Institute. Nearly 45 percent of them live in camps. According to the nongovernmental organization Anera, “In some Lebanese camps, when the winter rains come, raw sewage washes into people’s homes.” In 2012, a Lancet study published to assess the health and living situation of Palestinian refugees residing in these camps found that 31 percent had chronic medical conditions and 55 percent experienced “psychological distress.” Not only is gender-based violence a major issue in these camps, but according to UNRWA, “[v]iolent clashes [among various groups] are [also] a regular occurrence.”

In another example of the dire conditions of Palestinians, in Gaza, the poverty rate is more than 80 percent, as is the percentage of people dependent on humanitarian assistance. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate was 47 percent as of August 2022. Anera reports that in 2017, 13 percent of the youth population faced malnutrition. And that was before Israel started its genocidal bombing and invasion campaign.

Like many Palestinians, a lot of refugees retain a strong desire to return to their home country, should conditions once more allow for it to be safe for them to go back. But few have the opportunity—for example, in the first eight months of 2023, less than 25,000 Syrian refugees were able to return to the country.

Others, like Amari, wish to resettle in Europe, Canada, or elsewhere. But for now, they are stuck in squalid camps.

By Saurav Sarkar

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Saurav Sarkar is a freelance movement writer, editor, and activist living in Long Island, New York. They have also lived in New York City, New Delhi, London, and Washington, D.C. Follow them on Twitter @sauravthewriter and at sauravsarkar.com.

Source: Globetrotter

PVV Blog 2 ~ The Evil French Revolution Has Made Islam Even More Evil

01-08-2024 ~ Liberty, Equality and Fraternity

01-08-2024 ~ Liberty, Equality and Fraternity

Our democracy is indebted to the slogan of the French Revolution ‘Liberty, Equality and Fraternity’, but Party for Freedom leader Geert Wilders rejects the same French revolution.

He even draws a remarkably negative connection between the French Revolution and the world of Islam. What is the common thread behind this connection?

The bloodthirsty history of Islam

In his book Marked for Death. Islam’s War Against the West and Me Wilders describes parts of the history of Islam, based on his view that Islam is an aggressive totalitarian ideology and not a religion. Wilders deals extensively in descriptions of Muslim’ wars of conquest, the genocides they allegedly committed and the slave system they maintained. He also discusses the position of dhimmis, who are usually Jews and Christians, and who have a separate civil status within Islam, with fewer rights than Muslims. Nowhere does Wilders mention a positive aspect of Islam. Islam experienced a period of prosperity and growth from the beginning of its origins in the seventh century but fell into a subordinate position with the rise of Europe as the most powerful continent in the world from around the seventeenth century onwards.

The French Revolution inspires the Muslims

An interesting turning point in Wilders’ description of the alleged violent history and nature of Islam is the following. While in his book he discusses the emerging European supremacy over the world in the seventeenth century and beyond, with Islamic countries falling into the hands of Britain (such as Pakistan), France (Algeria), Italy (Libya), Spain (Spanish Sahara) and the Netherlands (Dutch East Indies), Wilders comes to the following insights: ‘when all seemed lost… Allah saved Islam, orchestrating what in Islamic eyes must look like two miraculous events: the outbreak of the French Revolution and the West’s development of an unquenchable thirst for oil’ (p. 112). Paradoxically, Allah was the driving force behind the French Revolution. In Wilders’ words, this is the same revolution that ‘revamped Islam at a crucial moment when its resourceswere diminishing due to its lack of innovation, the decline of its dhimmi population (i.e., Jews and Christians), and dwindling influxes of new slaves’ (p. 113)’.

Muslims cannot do it alone

Wilders’ reasoning is that Islam in itself stimulates neither development nor creativity. It depends on dhimmis and slaves to live and survive. Now that dhimmis and slaves had been exploited to the bone at the end of the eighteenth century, Islam needed new resources and innovations: the French Revolution provided this. After all, according to Wilders, one of the dogmas of the French revolutionaries was the complete submission of the entire people to the all-powerful state. The French showed the Muslims how they were able to subjugate their own people and virtually all European nations on the continent (at his height, Napoleon controlled large parts of the European continent; JJdR) to the principles of their ideology. It rang a bell and stimulated Muslims to become aware of their glorious past again, or in the words of Wilders: ‘In a sense, Islam encountered a “kindred soul” in Western totalitarian revolutionary thinking’ (p. 113). The line of reasoning is complex. Wilders is convinced of the aggressive character of Islam. Islam had somehow, paradoxically, and against its nature, fallen asleep in the centuries leading up to the French Revolution. God saved Islam by, again paradoxically, allowing the anti religious French Revolution to happen. When the French came to Egypt in 1798, they made the lethargic Muslims remember their glorious past.

Feeling inspired again, they rose to try to restore their once so beautiful empire.

Revolutionary France, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany: it’s a mess

Wilders rejects the French Revolution. In his book he blames Enlightenment thinking for the totalitarian character of the French Revolution. The French Revolution may have given rise to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, the basis of the current Charter of the United Nations, but Wilders still condemns it for its alleged totalitarian character, which culminated in the terror of the guillotine under Robespierre’s reign of terror. He calls Revolutionary France an ‘ideocratic state’ and groups it together with other ‘ideocratic’ states: ‘… such states –whether revolutionary France, the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany – exterminated their perceived enemies with guillotines, gulags and gas chambers’ (p. 32). Not a word in his book about the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or about the principle of human equality, which were also the fruits of this revolution.

Evil encourages evil

The French Revolution was nothing if not evil, and it is this evil that has awakened that other sleeping evil. ‘Islam began from the nineteenth century onward parroting Western

revolutionary jargon, adopting Western technological and scientific innovations, and embracing the belated industrial revolution that Western colonial administration was

bringing to the Islamic world – all with the goal of advancing jihad and world domination’ (p.114). This again sounds like a paradox for a religion that developed independently for the first 1200 years, but apparently that situation had changed. The key question for Wilders is that ‘exposure to Islam is ultimately fatal to us, but for Islam, contact with the West is a vital lifeline. Without the West, Islam cannot survive’ (p. 116). It is a deeply melancholy look at a religion that also produced the Taj Mahal and the Alhambra.

Cut the tires and let them die

Wilders’ view that the West is essential for Islam gives the same West an unexpected dominant position over Islam. If a country wants to get rid of its Muslims, all it has to do is cut ties with the community. The community then dies off automatically. How this should be done is of course a big question, but it will not be a pleasant operation. Cutting ties with Muslims will certainly not become a goal of the new Dutch government under Party for Freedom leadership, currently under construction, the other future coalition parties will not accept that, but it is my belief that it will remain an important ideological driving force in everything the new government will decide: How will measures and legislation in any area, but especially culture and education, ensure that the role of Islam and Muslims in the Netherlands is reduced? The anti-Islam ideology is in the DNA of the Party for Freedom and we will see it surface sooner or later.

Previous posts:

https://rozenbergquarterly.com/pvv-blog-introduction-the-dutch-party-for-freedom-an-analysis-of-geert-wilders-thinking-on-islam/

https://rozenbergquarterly.com/pvv-blog-1-geert-wilders-islam-is-not-a-religion-it-is-a-totalitarian-ideology/

The Right To Housing, Not Vacation Homes

Sonali Kolhatkar – Photo: sonalikolhatkar.com

01-07-2024 ~ Can strict regulations on Airbnb solve the housing crisis? Probably not, but they’re a good start.

Americans have been on a vacation binge since the easing of COVID-19 lockdowns, traveling for leisure in record numbers, and generating a major boom for the tourism industry. The vacation rental company Airbnb in particular, built on the euphemistic-sounding idea of a “sharing economy,” is thriving. In the third quarter of 2023, the company posted its highest-ever profits on record.

But increasingly, cities are seeing rising rents, unaffordable home prices, and increased homelessness. Authorities are linking such housing-related crises in part to Airbnb, and are passing strict regulations.

I’ve rented several Airbnb homes over the 15 years since the company was founded. In the early years, staying in other people’s houses was a sort of subversive act of rebellion against corporate hotel chains. During the most terrifying pre-vaccine months of the COVID-19 pandemic, short-term home rentals felt significantly safer than hotels, amid fears of the deadly airborne virus spreading among unmasked crowds in elevators and hotel lobbies. The privacy, convenience, and lower cost often enabled tourists with tighter budgets to enjoy family vacations with members of their chosen pandemic pods.

But, while Airbnb rentals may offer some financial respite for low-budget vacationers, their counterparts in the neighborhoods they visit are often negatively impacted by higher-cost housing prices and rents. What’s more, Airbnb hosts are increasingly professional landlords—wealthy elites and corporate entities that scoop up large numbers of properties and turn big profits by renting them out to travelers.

Even individuals managing a single property are now encouraged to expand vacation rental management into a full-time business. “Becoming an Airbnb property manager can be a fulfilling career path—and you can also make a lot of money with it,” claimed one company specializing in training professional hosts. “It’s a relatively low-risk, low-investment venture that can turn out to be extremely lucrative.”

Indeed, just as companies like Uber were once touted as a way for working people with cars to earn a little extra spending cash, Airbnb offered the promise of supplementary income for those with an extra room or converted garage. Now, however, the market is being increasingly dominated by a small number of corporate “hosts” and professional property managers.

Airbnb homes are available all over the world but the United States is most deeply affected. Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky said in late 2023, “[O]ur penetration in the United States is significantly higher than our penetration in many other countries. And we think there’s a huge amount of growth if we could just get Airbnb to even a fraction of the percentage of penetration that we have in the United States.” In other words, the U.S. is the model that Airbnb wants to replicate everywhere else in its quest for profits.

Stephanie Synclair is an appropriate symbol of what Airbnb has wrought in the U.S. The 41-year-old Black mom from Atlanta recently made the news for becoming a home-buyer, not in her own hometown, but in Sicily. In spite of the language and cultural barriers, Synclair purchased a home on the other side of the planet, in part because she found Sicilians to be warm and welcoming, but mostly because of the huge price difference. In spite of having a budget of $450,000—no small sum—Synclair had no luck buying a home in Atlanta, where properties are among the most overpriced in the nation. She now plans to retire in her $62,000 home in Palermo, Sicily.

Atlanta’s housing market is dominated by investors and cash-rich corporations who scoop up practically every home listed at $500,000 or less, many of which are then transformed into Airbnb listings for tourists. Precious Price, an Atlanta-based host, initially saw Airbnb as a pathway to building wealth, particularly for Black entrepreneurs like her who faced racial discrimination from the financial industry. But Price soon realized, according to a profile in the New York Times, that her rental property was part of the housing crisis that her beloved city was experiencing. She has since pivoted to long-term rentals aimed at residents rather than vacationers—an enterprise that is less profitable but more ethical.

Not only does Airbnb fuel housing crises in cities, it does so along racial lines. A 2017 study of New York City by the watchdog group Inside Airbnb concluded that the company’s model fuels racism in the housing market. Analyzing the demographics of rental hosts in the city, Inside Airbnb concluded, among other things, that “[a]cross all 72 predominantly Black New York City neighborhoods, Airbnb hosts are 5 times more likely to be white.” Further, “[t]he loss of housing and neighborhood disruption due to Airbnb is [six] times more likely to affect Black residents.” White New Yorkers have benefitted from renting out housing as hotels, while Black New Yorkers are disproportionately hurt.

To curb such inequities, New York City, which already had strict rules on the books about short-term rentals and subleases, passed a law in 2023 requiring Airbnb to ensure that hosts obtain permission to rent out housing. If it fails to do so, both the host and the company are hit with hefty fines.

The New York Times explained, “In order to collect fees associated with the short-term stays, Airbnb, Vrbo, Booking.com and other companies must check that a host’s registration application has been approved.” And, “hosts who violate the rules could face fines of up to $5,000 for repeat offenders, and platforms could be fined up to $1,500 for transactions involving illegal rentals.”

It was an admission that the earlier set of rules was simply not being enforced—as we continue to see in cities like Los Angeles—where hosts flout rules with little consequence. But now, at least in New York City, the onus is on the company, as well as the hosts to comply.

While this means potentially higher hotel costs for out-of-town visitors, it could free up rentals for long-term residents. According to the Guardian, this may already be happening, just months after the law went into effect in September: “[T]he city’s rental costs are backing off from record highs, as the vacancy rate increases to a level not seen in three years—good news for folks looking to sign rental leases.”

While cheaper vacation stays are certainly desirable for those of us who love to travel, vacationing is a privilege in the U.S. More than a third of Americans, as per a 2023 survey, are unlikely to take a summer vacation. And of those, more than half say they simply can’t afford it. A 2019 Economic Policy Institute study pointed out that “Airbnb might, as claimed, suppress the growth of travel accommodation costs, but these costs are not a first-order problem for American families.” What is a first-order problem is affordable housing.

And, while regulating Airbnb will not mitigate all economic injustices facing Americans—such as suppressed wages and a lack of government-funded health care—it certainly will move the needle in the right direction.

By Sonali Kolhatkar

Author Bio: Sonali Kolhatkar is an award-winning multimedia journalist. She is the founder, host, and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a weekly television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. Her most recent book is Rising Up: The Power of Narrative in Pursuing Racial Justice (City Lights Books, 2023). She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and the racial justice and civil liberties editor at Yes! Magazine. She serves as the co-director of the nonprofit solidarity organization the Afghan Women’s Mission and is a co-author of Bleeding Afghanistan. She also sits on the board of directors of Justice Action Center, an immigrant rights organization.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Elections In Taiwan: Does The Island Choose Further Confrontation With China?

Taiwan – Map: Wikimedia Commons

01-07-2024 ~ On January 13, the residents of Taiwan, an island off the coast of China, will go to the polls to elect a new president and parliament. These elections attract more international attention than one might expect for a country with only 24 million inhabitants. The outcome will have consequences for the evolution of the conflict between the United States and China, and consequently, possibly for world peace.

Two weeks before the elections, I spoke with Wu Rong-yuan, the chairman of the Labor Party of Taiwan, in the capital, Taipei. His party is contesting seats in three districts. Due to the first-past-the-post system, this is an uphill battle. Moreover, the Labor Party is marginalized due to its pro-reunification stance with China. To better understand this, I let the veteran of the labor struggle explain the history to me once again.

Taiwan lived under the dictatorship of the Kuomintang, Chiang Kai-shek’s party, until 1987. The roots of the Kuomintang are on the mainland of China, where they were in power until the victory of the socialist revolution in 1949. Even after the end of the dictatorship, the party continued to rule in Taiwan, officially still named the Republic of China, and initiated a process of democratization. Meanwhile, the main opposition coalesced around the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).

For a long time, the island’s politics were a two-way contest between the Kuomintang and the DPP. Almost all other, much smaller, political forces sided with either the blue or the green coalition, corresponding to the respective colors of the two parties. While the Kuomintang sees the island as part of China, the DPP is unequivocally in favor of an independent Taiwan.

In 2000, the DPP came to power for the first time. After an eight-year hiatus, that happened again in 2016. They not only had the president, Tsai Ing-wen but also governed with a majority in the parliament. It is under Tsai that tensions with China increased further, fueled by the United States.

Wu explained to me that the economic positions of both parties are not significantly different. Both align themselves with the U.S. “Moreover, they also find common ground in anti-communism against the rulers in Beijing,” said Wu, “but while the Kuomintang claims that the residents of Taiwan and the mainland of China form one Chinese nation, separated by the sea and different ideologies, the DPP invented Taiwanese nationalism: Since they came to power 23 years ago, they managed to create a distinct Taiwanese identity out of nothing.”

This does not mean that all Taiwanese support the DPP’s course. On the contrary, the popularity of the ruling DPP has significantly declined. Normally, the opposition would win these upcoming elections hands down. The population is divided over the right stance toward China. The extension of military service from four to 12 months makes the looming military escalation suddenly very concrete. The energy crisis, on the other hand, symbolizes the country’s poor economic performance. The population is far from satisfied with the government’s policies.

A sure win for the Kuomintang, then? Not quite, because this time there is a third party that can convince a significant portion of the voters. The recently established Taiwan People’s Party presents itself as an alternative to the blue and green alliances, putting forward a credible candidate for the presidency, the former mayor of Taipei. It briefly seemed like this party would form a joint presidential ticket with the Kuomintang, but in November, they ultimately chose to run separately.

With a divided opposition, the DPP could still win the elections. The presidential candidates of the DPP and the Kuomintang are neck and neck in the polls. No one can predict who will win. However, the rise of a third party has an important consequence: Regardless of who wins the presidential elections, they will likely not have a majority in the parliament. This means compromises will have to be made.

According to Wu Rong-yuan, these are crucial elections for the relations between Taiwan and China. The Kuomintang advocates the status quo which means that both recognize there is one China but have different interpretations about what this means. The DPP wants to assert Taiwan’s status as an independent country and can count on U.S. support for that. “The confrontational policy of the U.S. makes the status quo impossible,” says Wu, “while the independence the DPP seeks, isolates us from the mainland and goes against the interests of the workers.”

Wu finally explains the vision of the Labor Party: “Reunification between Taiwan and China is the only path to peace and prosperity: ‘One country, two systems’ is a realistic formula.” On the question of whether this would be based on the arrangement with Hong Kong, the answer is negative: “China has clearly stated that Taiwan would have more autonomy, and there are good reasons for that: Hong Kong was a colony of Britain when it was transferred to China, while Taiwan has existed for decades as an autonomous economic and political entity.”

Although there seems to be little openness from the two traditional parties for now, the Labor Party hopes that there will be room for dialogue between Taipei and Beijing after the elections: “There is no model for reunification, and it is only through dialogue and exchange that we can find solutions.”

By Wim De Ceukelaire

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Wim De Ceukelaire is a health and social justice activist and member of the global steering council of the People’s Health Movement. He is the co-author of the second edition of The Struggle for Health: Medicine and the Politics of Underdevelopment with David Sanders and Barbara Hutton.

Source: Globetrotter