Why Capitalism Cannot Finally Repress Socialism

Richard D. Wolff

Socialism is capitalism’s critical shadow. When lights shift, a shadow may seem to disappear, but sooner or later, with further shifts of light, it comes back. Capitalism’s ideologues have long fantasized that capitalism would finally outwit, outperform, and thereby overcome socialism: make the shadow vanish permanently. Like children, they bemoan their failure when, in the light of new social circumstances, the shadow reappears clear and sharp. Recent efforts to dispel the shadow having failed again, the contest of capitalism versus socialism resumes. In the United States, young people especially applaud socialism so much recently that think tanks like PragerU and the Hoover Institute at Stanford University urgently recycle the old anti-socialist tropes.

In fact, the capitalism-versus-socialism contest does not really resume because it never really stopped. As changing social conditions changed socialism—a process that took time—it sometimes seemed to wishful thinkers that the systems struggle had ended with capitalism’s victory. Thus the 1920s saw anti-socialist witch hunts (especially the Palmer raids by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Sacco and Vanzetti persecution) that many believed at the time would extinguish U.S. socialism. What had happened in Russia in 1917 would not be allowed to sneak into the United States with all those European immigrants. The grossly unfair Sacco and Vanzetti trial (recognized as such even by the state of Massachusetts) did little to prevent—and much to prepare for—subsequent similar anti-socialist efforts by government officials in the United States.

With the 1929 crash, socialism revived to become a powerful movement in the United States and beyond during the 1930s and 1940s. After World War II ended, the political right and most major capitalist employers tried once again to squash capitalism’s socialist shadow. They fostered McCarthy’s “anti-communist” crusades. They executed the Rosenbergs. By the end of the 1950s, once again, many in the United States could indulge the thought that capitalism had vanquished socialism. Then the 1960s upset that indulgence as millions—especially young people—enthusiastically rediscovered Marx, Marxism, and socialism. Shortly after that, the Reagan and Thatcher reaction tried a bit differently to resume anti-socialism. They simply asserted and reasserted to a receptive mass media that “there is no alternative” (TINA) to capitalism any longer. Socialism, where it survived, they insisted, had proved so inferior to capitalism that it was fading in the present and possessed no future. With the 1989 collapse of the USSR and Eastern Europe, many again believed that the old capitalism versus socialism struggle had finally been resolved.

But of course, the shadow returned. Nothing more surely secures the future of socialism than the persistence of capitalism. In the United States, it returned with Occupy Wall Street, then Bernie Sanders’s campaigns, and now the moderate socialists bubbling up inside U.S. politics. Each time Trump and the far right equate liberals and Democrats with socialism, communism, Marxism, and anarchism, they help recruit new socialists. Socialism’s enemies understandably exhibit their frustration. With so little exposure to Hegel, the idea that modern society might be a unity of opposites—capitalism and socialism both reproducing and undermining one another—is not available to help them understand their world. Read more

Insecurity Is A Feature, Not A Bug, Of Capitalism. But It Can Spark Resistance

Astra Taylor – Photo: en.wikipedia.org

Debt abolitionist Astra Taylor discusses how capitalism’s manufactured insecurity can feed movements for radical change.

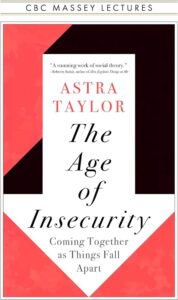

Capitalism is a socioeconomic system that depends upon exploitation and generates inequality. In a recently published book titled, The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart, filmmaker, writer and political organizer Astra Taylor also describes capitalism as an inherently insecurity-producing machine.

From education and home ownership to workplace surveillance, capitalism manufactures insecurity, argues Taylor, a co-founder of the Debt Collective. This insecurity makes us increasingly vulnerable to economic uncertainty, which the system weaponizes in turn against us.

Yet, Taylor argues in the exclusive interview for Truthout, the system’s manufactured insecurity can also band people together to demand radical reforms, although insecurity in today’s world seems to be drawing people increasingly toward authoritarian political leaders.

C. J. Polychroniou: It is often said we live in strange and dangerous times. Indeed, there are crises in place which threaten human survival; there is continuous growth in economic inequality since the 1980s and authoritarianism is on the move as democracy weakens. In this context, in your recently published book aptly titled, The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart, you have described insecurity as a “defining feature of our time” and an essential feature of the capitalist system. Now, capital reigns, to be sure, and capitalism exploits insecurities, but isn’t occasional insecurity also a natural part of life? Why make insecurity a driving force behind today’s economy and politics? Why not resentment, or protest actions, which are growing throughout the world, although some studies indicate that the same thing is happening with political apathy?

Astra Taylor: Insecurity relates to the many intensifying and intersecting crises we face today — unaffordable housing, rising debt, toxic media, worsening mental health, an emboldened far right, climate catastrophe, Artificial Intelligence and Big Tech, the list goes on.

I wouldn’t say that I “make” insecurity a driving force behind today’s politics. I’d argue that it just is one. That’s because, as I show in the book, insecurity is a defining component of capitalism — one as essential as the profit motive. To paraphrase your question, capitalism not only exploits insecurities; more fundamentally, it generates them.

Insecurity, in other words, isn’t just an unfortunate byproduct of our current competitive economic order. It’s a core product. If you aren’t insecure, you don’t keep buying, hustling, accumulating. Insecurity is the stick that keeps us scrambling and striving.

And yet, as you note, insecurity is also a natural part of life.

In the book, I distinguish between two kinds of insecurity. First there is existential insecurity, or the kind of insecurity that is inherent to human life and that stems from the fact we are mortal creatures who can’t survive without the care of others. Then there is what I call manufactured insecurity, and this is the kind of insecurity that is essential to the functioning of a market society.

Looking back over the centuries to the dawn of the industrial era, I show how capitalism began by making people insecure in this modern sense — by severing people from their communities and traditional livelihoods so they had nothing to sell but their labor. We see this dynamic playing out today, as officials pursue monetary policies explicitly designed to weaken the hand of workers. That’s the manufactured insecurity at work.

This might all sound rather heavy, but I really tried to write the book with a light touch — drawing on history and economics while also incorporating myth, psychology and even some humorous memoir elements. And there’s hope. Right now, our society is structured to worsen rather than tend to our insecurities and vulnerabilities. But we can always arrange things differently.

The notion of insecurity as a feature in today’s world might lead people to assume that it leads to despair and inaction. Yet, you argue that insecurity can indeed be a step toward creating solidarity for the purpose of challenging and eventually transforming the system. Is this a theoretical statement behind the purported symbiotic relationship between capitalism and insecurity, or one based on actual empirical evidence? In other words, can you describe how insecurity translates into collective action and what form, in your own view, collective action needs to take for the system to be transformed?

The notion of insecurity as a feature in today’s world might lead people to assume that it leads to despair and inaction. Yet, you argue that insecurity can indeed be a step toward creating solidarity for the purpose of challenging and eventually transforming the system. Is this a theoretical statement behind the purported symbiotic relationship between capitalism and insecurity, or one based on actual empirical evidence? In other words, can you describe how insecurity translates into collective action and what form, in your own view, collective action needs to take for the system to be transformed?

In the book, I argue that insecurity can cut both ways. It can spur defensive and destructive compulsions, or it can be a conduit to empathy, humility, belonging and solidarity. We see this all the time. The right wing knows this and is dedicated to inflaming people’s insecurities, encouraging them to misdirect their rage toward the even-more-vulnerable — rather than toward the economic system and the elites who profit from the status quo.

One example I give is how workers and the unemployed organized during the Great Depression. We forget it today, but “insecurity” was actually a critical concept in the battle for the New Deal. Franklin Roosevelt called insecurity “one of the most fearsome evils of our economic system” and made the concept of security a cornerstone of the welfare state. I certainly see insecurity — shame, fear, anxiety about the future — transformed into solidarity in my work with the Debt Collective, the union for debtors that I helped found.

In today’s economic climate, the rental housing crisis has become particularly acute in thoroughly neoliberal societies like the United States, but rents have also exploded across Europe and more and more people are facing precarious living conditions. Are there innovative solutions for the rental housing crisis? For example, can Vienna’s social housing policy be duplicated in countries like the United States?

Absolutely. I spend some time on the example of Austrian social housing in the second chapter of the book. It’s a fantastic example of how to eradicate a form of material insecurity that is now depressingly endemic across North America.

In the book, I return again and again to a core paradox. As I write, “Today, many of the ways we try to make ourselves and our societies more secure — money, property, possessions, police, the military — have paradoxical effects, undermining the very security we seek and accelerating harm done to the economy, the climate, and people’s lives, including our own.”

Housing really is a prime example. In the U.S., a paltry 1 percent of housing is provided on a non-market basis. The commodification of housing ensures that huge numbers of people will be priced out and perpetually insecure and also unhoused. The very thing that we are told will finally guarantee us security — a mortgage on a one-family unit — also helps drive the destabilization of our communities. Ever-appreciating values and rents push working-class people out of their towns and neighborhoods. Single-family, car-dependent fiefdoms are ecologically wasteful. Not to mention the way the financial sector and the rise of Wall Street landlords are further enriched by this model, further contributing to volatility. Social housing is the only way out of this conundrum, and the only way to ensure real housing security for all.

The Biden administration has made inroads on student debt, but student debt cancellation is still far from becoming a reality, largely because of the Supreme Court’s ultraconservative majority. First, I would like you to explain to readers why the Debt Collective, which you co-founded in 2014 and which happens to be the first union for debtors, talks about “debt cancellation” and rejects the term “debt forgiveness,” and then whether you remain optimistic that an ultimate victory for student-loan borrowers is going to happen at some point down the road.

We reject the idea of “debt forgiveness” because debtors did nothing wrong. People don’t need to be forgiven for pursuing an education — for wanting to learn or to better their lives. This is why the Debt Collective prefers to speak of debt “cancellation,” “relief” or “abolition.”

Our small-but-mighty movement has come a long way in a decade. I believe that we will win — if people get off the sidelines and join us. One easy way people reading can do that is by taking 10 minutes to submit a dispute to the Department of Education using our new Student Debt Release Tool. Anyone with federal loans can do so. The tool will send a former letter demanding relief to the top brass at the Department of Education. The more applications they receive, the more pressure we can apply.

We’ve had victories, we’ve had setbacks, and then more victories and setbacks. I’ve been in the trenches long enough to know that’s how movements go. The arc of justice is, sadly, rather crooked and sometimes loops back on itself. But this is not a moment to throw up our hands — it’s one to keep holding the president’s feet to the fire. The movement for debt abolition is just getting started.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

“Capitalism Is an Insecurity Machine”: Astra Taylor on Student Debt & Our Radically Unequal World

As the COVID-19 era pause on federal student debt payments comes to an end and some 40 million Americans will resume payments next month, we speak with Debt Collective organizer Astra Taylor about Biden’s new Saving on a Valuable Education, or SAVE, plan and her organization’s new tool that helps people apply to the Department of Education to cancel the borrower’s debt. Taylor also discusses her new book, The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart, in which she writes, “How we understand and respond to insecurity is one of the most urgent questions of our moment, for nothing less than the future security of our species hangs in the balance.” She notes organizing is about “the alchemy of turning our vulnerabilities, turning our oppression, turning our insecurities into solidarity so that we can change the structures that are undermining our self-esteem and well-being.”

Democracy Now! is an independent global news hour that airs on over 1,500 TV and radio stations Monday through Friday. Watch our livestream at democracynow.org Mondays to Fridays 8-9 a.m. ET.

The Case For Protecting The Tongass National Forest, America’s ‘Last Climate Sanctuary’

Tongass National Forest. – Photo: en.wikipedia.org

The “lungs of North America,” the Tongass National Forest is the Earth’s largest intact temperate rainforest. Protecting it means protecting the entire planet.

Spanning 16.7 million acres that stretch across most of southeast Alaska, the Tongass National Forest is the largest national forest in the United States by far and part of the world’s largest temperate rainforest. Humans barely inhabit it: About the size of West Virginia, the Tongass has around 70,000 residents spread across 32 communities.

A vast coastal terrain replete with ancient trees and waterways, the Tongass is a haven of biodiversity, providing critical habitat for around 400 species, including black bears, brown bears, wolves, bald eagles, Sitka black-tailed deer, trout, and five species of Pacific salmon.

The Tongass is a pristine region that supports a vast array of stunning ecosystems, including old-growth forests, imposing mountains, granite cliffs, deep fjords, remnants of ancient glaciers that carved much of the North American landscape, and more than 1,000 named islands facing the open Pacific Ocean—a unique feature in America’s national forest system.

The Tongass “is the crown jewel of America’s natural forests,” declared then-Senator Barbara Boxer (D-CA) during Senate deliberations of Interior Department budget appropriations in 2003. “When I was up there, I saw glaciers, mountains, growths of hemlock and cedar that grow to be over 200 feet tall. The trees can live as long as a thousand years.”

The National Forest Foundation calls the Tongass National Forest “an incredible testament to conservation and nature.” But since the 1950s, the logging industry has prized the forest, and the region has been threatened by companies that seek to extract its resources—and the politicians who support these destructive activities.

America’s Largest Carbon Sink

Carbon sinks absorb more carbon from the atmosphere than they release, making them essential to maintaining natural ecosystems and an invaluable nature-based solution to the climate crisis. Between 2001 and 2019, the Earth’s forests safely stored about twice as much carbon dioxide as they emitted, according to research published in 2021 in the journal Nature Climate Change and available on Global Forest Watch.

The planet’s forests absorb 1.5 times more carbon than the United States emits annually—around 7.6 billion metric tons. Consequently, maintaining the health of the world’s forests is central to humanity’s fight against climate change. But rampant deforestation and land degradation are not only removing this invaluable climate-regulating ecosystem service and supporter of biodiversity but also disturbing a healthy, natural planetary system that has existed for millennia.

“There is a natural carbon cycle on our planet,” said Vlad Macovei, a postdoctoral researcher at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon in Germany. “Every year, some atmospheric carbon gets taken up by land biosphere, some by the ocean, and then cycled back out. These processes had been in balance for the last 10,000 years.” Read more

Why China’s New Map Of Its Borders Has Stirred Regional Tensions

John P. Ruehl – Source: Independent Media Institute

10-17-2023 ~ China’s release of its standard map has produced outrage and alarm in several countries, yet Beijing remains steadfast in continuing its historical approach toward its borders.

In the waning days of August 2023, closely following a BRICS summit and mere days ahead of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and G20 meetings, Beijing revealed its latest seemingly innocuous “standard” map. Having been released regularly since at least 2006, China’s standard maps are aimed to eliminate “problem maps” that do not affirm China’s territorial integrity. But the 2023 edition invited ripples of condemnation throughout China’s near abroad and beyond, as it repeated Beijing’s claims on divisive territorial disputes with its neighbors—including the Philippines, which has seen its struggle with China over a small shoal in the South China Sea escalate significantly over recent weeks.

The release of China’s map, coupled with its aggressive border strategies, has created enormous uncertainty across the Indo-Pacific. In a rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape, various actors are wrestling with how to effectively counter China’s actions.

China’s perception of maritime and international laws as products of Western customs has underpinned its level of adherence to them. “Stealthy compliance” allows China to ambiguously accept international law while interpreting it flexibly to advance its territorial claims. Beijing will also explicitly reject international law, exemplified by its dismissal of a tribunal in The Hague that challenged China’s assertions in the South China Sea in 2016. Regularly publishing maps helps assert China’s claims to domestic and international audiences, without putting Beijing in a position where it has to enforce them simultaneously.

Beijing’s strategy has effectively thwarted regional and Western responses and prevented the outbreak of major conflict. Inflaming territorial disputes serves as a bargaining chip in bilateral negotiations and lays the groundwork for potential future claims as China’s strength is expected to increase. Channeling nationalist sentiment outward has also bolstered the Chinese government’s domestic legitimacy and diverted attention from contentious issues like Tibet, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong.

However, the response to China’s 2023 map reveals growing backlash to Beijing’s approach to its border issues and questions over its long-term sustainability.

China has periodically unveiled its nine-dash line map for decades, delineating its claims in the South China Sea. The mystery shrouding whether these claims pertain to water rights, land features, or both, has kept the region on edge. Regardless, they symbolize China’s desire to reduce U.S. control over regional shipping lanes, secure rights over natural resources, and project power beyond its first island chain into the expansive Pacific.

China’s latest map took a bold step by reintroducing a tenth dash east of Taiwan—a largely dormant claim since 2013. The move not only reaffirmed China’s ownership of Taiwan but also extended China’s reach beyond Taiwan’s recognized territorial waters, a direct challenge to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Reasserting this claim may point to growing confidence in Beijing of being able to impose its various claims in the region. China’s map also continued to emphasize China’s rights to the Senkaku Islands, disputed with Japan. Both Taipei and Tokyo vehemently criticized China for the map’s release.

China and ASEAN had meanwhile been negotiating a code of conduct for the South China Sea, reaching an agreement in July to accelerate the process. The release of the 2023 map just days before the ASEAN summit in Indonesia naturally triggered swift rejection from member states such as Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, which have longstanding wariness of Chinese maritime territorial ambitions. Read more

G7 Versus BRICS: Power Struggles Are Not Class Struggles

Richard D. Wolff

Class struggles interact with but are different from power struggles. The ancient conflicts between city-states Athens and Sparta were power struggles, while within each, slaves and enslavers engaged in class struggles. Britain and France were absolute monarchies in late European feudalism fully engaged in power struggles. At the same time, class struggles between lords and serfs internally agitated both “great” powers. Now, after slavery and feudalism have largely ended and capitalism prevails globally, great power struggles exist between the G7 and BRICS and among their member nations, as well as other nations. At the same time, class struggles exist between employers and employees in all nations. Power and class struggles condition and shape one another. Both have been and remain core aspects of history; so too have ideological habits of confusing and conflating them.

Kaiser Wilhelm II, Germany’s monarch, said in 1914 as World War I began, “I no longer recognize [political] parties, I recognize only Germans.” He used nationalism to unify a class-divided Germany to help win the war. The Kaiser had been shaken by more than the increasingly serious struggles among world powers over colonies, world trade, and foreign investment. He was stunned too by the rise of Germany’s Marx-inspired Socialist Party across the decades before the war. Germany’s class of capitalist employers had been similarly shaken and stunned. For a country increasingly and deeply split between labor and capital, German nationalism was the employer class’s strategy both to thwart socialism and win the war. Key to that strategy was getting people to think (and self-identify) in terms of national and ultimately military struggles, and not class struggles.

Germany’s strategy failed. It lost World War I, the monarchy ended, and its Socialist Party became Germany’s postwar government. Socialism emerged from the war far stronger in Germany than it had ever been. Much the same was true for World War I’s other combatant nations. More or less all of them had used nationalism to mobilize their war efforts and to undermine and displace class consciousness. For the war’s winners, nationalism may have served its purpose for them to achieve victory. Yet, it did not vanquish or banish socialism. Instead, socialism captured its first government (Russia) and split into socialist and communist wings that each drew mass attention and engagement. Both wings spread globally and quickly in the 1920s and even more in the 1930s as capitalism imposed its worst crash ever on most nations across the world.

Now, a century later, power struggles intensify and sharpen across global capitalism. The power of the United States, hegemonic during the Cold War, is now declining. The earlier decline of Europe, punctuated by the loss of its colonies and two deeply destructive world wars, continues. Both Europe and the United States face the stunning, unprecedented speed of China’s economic growth and concomitant rise to global power status. Already, China’s network of alliances, especially the BRICS, confronts the United States and its alliances, especially the G7. The rise of China and the BRICS adds to their power struggles with the United States and the G7. That rise is also realigning power relations between the Global North and Global South and, in one way or another, among all nations and within international organizations.

Class struggles have likewise continued in all societies, thereby evolving in different forms and foci. Most importantly, socialists now focus decreasingly on the struggle between private property and free markets as capitalism, versus state property and state planning as socialism. Many socialists reacted to 20th-century experiences with state power in the USSR and the People’s Republic of China by shifting their focus. State power and planning, while not dismissed as socialist goals, were seen increasingly as insufficient by themselves. Something more or different was needed to yield the post-capitalist system that socialists could and would embrace. Socialists refocused their priorities on the transformation of workplaces. Based on a critique of the capitalist hierarchy inside factories, offices, and stores—and its social effects—socialists increasingly stress proposals to democratically reorganize production there. Each worker in an enterprise will have an equal vote to decide what, where, and how to produce as well as how to dispose of the product (or net revenues where the product is marketed). The democratization of all workplaces (households as well as enterprises) becomes a central thrust of what socialism has come to mean. Read more