ISSA Proceedings 2006 ~ An Analysis Of Preschool Hebrew Speaking Children’s Arguments From The Perspective Of The Pragma-Dialectical Model

1. Characteristics of Children’s Verbal Arguments

1. Characteristics of Children’s Verbal Arguments

Verbal arguments are part of young children’s normal activity and are usually “rule governed and socially organized events” (Benoit 1992, p. 733). Researchers have concluded that they have a positive effect on friendships and cognitive development (Corsaro 1994, Dawe 1934, Garvey 1993, Green 1933, and Shantz 1987). Corsaro (1994, p. 22) states “disputes provide children with a rich arena for development of language, interpersonal and social organization skills, and social knowledge.” In fact, O’Keefe and Benoit (1982) see argument as part of normal language learning. Piaget (1952, p. 65) states “[i]t may well be through quarrelling that children first come to feel the need for making themselves understood”.

Children’s arguments are generally short in duration. For example, Dawe (1934) found that on average quarrels last 14 seconds, while O’Keefe and Benoit (1982) found that young children’s disputes consisted of an average of five turns. Although these disputes are not long in duration, they are powerful events. Once a dispute has begun, “any prior goal or task is abandoned and the attention is directed to resolving the incompatibility” but “[o]nce the conflict is resolved, play can once again be resumed” (Eisenberg and Garvey 1981, p.151). These verbal disputes can be considered as “side-sequences” (Jefferson, 1972), important at the moment, but with no lasting effect on interaction.

2. The Study and Research Question

This paper will report on ongoing research investigating the verbal arguments of Hebrew speaking pre-school children. The data for this research was transcribed from videotapes of fourteen triads of pre-school children at play in a playroom that was set up for the purpose of the study. The children are also in daily attendance at the same pre-school. The subjects’ ages ranged from 4 years six months to six years five months, however the maximum age differences of the children in each individual group was usually around six months. Children above the age of four were chosen since by this age normally developing children have acquired the basics of their language system (Brown, 1973). The children were all native speakers of Hebrew. While the children conducted their talk in Hebrew it was transcribed and translated simultaneously into English by the author.

While this is an ongoing study with a number of research questions, only one of these will be related to in this paper. This question is presented below:

Is the process of Israeli preschool children’s arguments consistent with the pragma-dialectical model of van Eemeren and Grootendorst (2004)? Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2006 ~ Putin’s Terrorism Discourse As Part of Democracy And Governance Debate In Russia

Abstract

Abstract

This paper [i] presents a study of President Putin’s use of the issue of terrorism in public debate in Russia. President Putin’s speech made in the wake of the Beslan tragedy, on September 4th, 2004, is examined. The logico-pragma-stylistic analysis employed in the paper describes communicative strategies of persuasion employed by the speaker and investigates how the Russian leader uses the issue of terrorism to further his political goals. The terrorism debate is analysed within a wider context of democracy and governance debate between the President and the liberal opposition.

Key words: argumentative discourse, rhetoric, pragmatics, pragma-dialectics, fallacies.

This paper is a study of the use of the issue of terrorism in public debate in Russia. It examines President Putin’s address to the nation in the wake of the Beslan terrorist attack, on 4 September 2004.

The study doesn’t pretend to be an exhaustive treatment of the topic; rather it aims to present a logico-pragma-stylistic analysis of the speech, to identify communicative strategies of persuasion employed by the speaker, and to investigate how the Russian leader used the problem of terrorism to further his political goals. The terrorism debate is analysed within a wider context of the democracy and governance debate between the President and a liberal opposition.

In trying to persuade his or her audience a skilled arguer assesses the audience and the issues at hand. When composing a message the speaker takes into account of several factors: the medium of communication (electronic mass media, print media), topic of discussion, audience (gender, level of education, expertise in the topic under discussion, rationality/emotionality, degree of involvement in the problem, level of life threat presented by the problem, etc), nature of the discussion (i.e. whether it is a direct dialogue with an opponent in a studio or an indirect dialogue through electronic or print media), applicable conventions (e.g. parliamentary procedures), and finally a broader, cultural and political context in which communication is taking place including such elements as openness/restrictiveness of the political regime, moral dilemmas and cultural taboos existing in the society, and traditions of conducting discussions inherent in the culture.

The process of assessment and adaptation of the issues to the audience establishes a communicative strategy of persuasion. The key decisions in a communicative strategy are to choose targets to appeal to and to prioritize them. While there are a wide variety of possible targets of appeal, it is possible to identify three major ones, people’s mind, emotions, and aesthetic feeling. An appeal to people’s reason or rational appeal is based on the strength of arguments. Emotional appeals arouse in the reader or listener various emotions ranging from a feeling of insecurity to fear, from a sense of injustice to pity, mercy, and compassion. Aesthetic appeals are based on people’s appreciation of linguistic and stylistic beauty of the message, its stylistic originality, rich language, sharp humour and wit. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2006 ~ Changing Our Minds: On The Value Of Analogies For Extending Similitude

Analogies are important in invention and argumentation fundamentally because they facilitate the development and extension of thought. (Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, The New Rhetoric)[i]

Analogies are important in invention and argumentation fundamentally because they facilitate the development and extension of thought. (Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, The New Rhetoric)[i]

In a recent article, A. Juthe notes that “it is not obvious that the most plausible interpretation [of an “argument by conclusive analogy”] is a deductive argument”; reconstructing those arguments as deductive, Juthe suggests, reveals “the perhaps too great influence of the deductive perspective in philosophy” (2005: 23). Juthe goes on to argue that “argument by analogy is a type of argument in its own right and not reducible to any other type” (16). In this paper, I extend Juthe’s analysis of analogical arguments in the interest of supporting an expansion of the category of argumentation in the public sphere beyond the traditional conception that’s valorized in Habermas’s conception of “communicative action.”

Analogical arguments may be assessed as valid, Juthe argues, by virtue of “a correlation or an intuitive connection based on our experience and background knowledge” (15). This conception suggests that there’s a major shift in orientation that’s needed to appropriately assess the value of analogical argumentation. More precisely, there are three shifts in orientation: reversing the relative importance usually allotted to properties in contrast to relations as well as to substances in contrast to events, when constructing arguments, and reversing the relative importance usually allotted to “warrant” in contrast to “background” when using the Toulmin model for argument analysis. Analysis of discussion of topics in public sphere argumentation suggests that we often rely upon analogical reasoning to propose alternatives to views propounded by discourse partners. Thus, examples in that domain inform my sense of the importance of analogical argumentation, background knowledge, temporality (events rather than substances) and relationality (correlations and counterparts, rather than identities) in mundane concept formation. It may be helpful to note that I am not concerned to reject the value of warranted arguments involving properties and substances. Rather, my interest is in valorizing analogical argument as worthy in its own right; as irreducible to other forms; and as a form of argument that bypasses what I suspect is a lurking remnant of that “perhaps too great influence of the deductive perspective in philosophy” that Juthe notices. That same influence, I suggest, may well be efficacious in what I argue elsewhere (Langsdorf 2000, 2002b) is a constrained conception of argumentation that limits, and even distorts, Habermas’s conception of “communicative action.”[ii]

This paper continues my previous work on the ontological aspect of articulation by focusing on analogical reasoning’s revelatory power in argumentation that seeks truth in Heidegger’s sense of “aletheia,” or “uncovering.” But that concept easily suggests a realist, in contrast to constitutive, basis for inquiry. Thus my initial task is to delineate the contrasts between realist and constitutive ontological starting points, in relation to dramatically different expectations as to what analogical arguments may accomplish. My further task concerns the implications that follow from acknowledging that these expectations are embedded in constitutive rather than realist ontologies; namely, we must assess their truth value by standards other than those more traditionally used in argumentation theory. In this paper I pursue only the initial task. The titles I use for the two orientations rely upon John Dewey’s identification of philosophy’s “proper task of liberating and clarifying meanings” as one for which “truth and falsity as such are irrelevant” (1925/1981, p. 307). Yet Dewey modifies that separation of “meanings” and “truth” by his recognition that “constituent truths,” in contrast to “ultimate truths,” rely on a “realm of meanings [that] is wider than that of true-and-false meanings.” My thesis, then, is that analogical reasoning’s value lies in uncovering alternate meanings by using the implicit “background knowledge” that’s intrinsic to any communicative situation. That knowledge includes “intuitive connections” that shape “wider” meanings – those meanings that propose “constituent truths” – and so “facilitate the development and extension of thought.” For that process of developing alternative possibilities and extending conventionally accepted meanings, I suspect, is crucial for that little-understood process we call changing our minds. Read more

Interests And Difficulties In Understanding Chinese Culture: What To Prepare For When Communicating With Cultural Others

Abstract

Because of the long history and richness of civilization in China (Leung, 2008; Liu, 2009; Hu, Grove, and Zhuang, 2010), as well as the complexity and diversity of Chinese culture in mainland China and in the Chinese community worldwide (The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987; Fan, 2000), the task of designing an introductory course on Chinese culture for Westerners presents certain difficulties (Luk, 1991; Fan, 2000). While the content of a comprehensive course on Chinese culture remains to be decided, the present study explores a 12-week introductory course on four areas of Chinese culture. It was delivered to 16 Irish students who were doing a degree in Intercultural Studies. Each participant was asked to write a 500-word reflective journal entry every two weeks and an essay of 2,000–2,500 words at the end of the course.

The study aims to find out which area(s) and topic(s) might be of interest to or potential obstacles for Irish students in future participation in intercultural dialogue with Chinese people. Using the software Wordsmith Tools (Scott, 1996), the study identifies both the area and the sub-topic within each area that are of greatest interest yet previously unknown to Irish students.

The results show that the section on “love, sex, and marriage in China” was very well received and the most discussed topic in their journals and essays. The participants demonstrated fascination with the changing role of women in Chinese culture and identified shared ground in terms of marriage choices in both Irish and Chinese societies, which could help them to develop a deeper understanding of Chinese society and participate in intercultural dialogue from this perspective. A number of topics, such as martial arts films, the urban/rural divide, loss of face, etc., can be employed as prisms through which students can explore and understand elements of Chinese culture and its evolution over time.

The understanding of “face” in Chinese culture is perceived by the participants as being of great importance in intercultural and interpersonal communication, which could undoubtedly support engagement in open and respectful exchange or interaction between the Irish and Chinese. Interestingly, the participants indicated that it is difficult to understand that the use of linguistic politeness could lead to the speaker being perceived as “powerless” in Chinese society, which could mean that not being aware of this might lead to miscommunication between individuals with different cultural backgrounds. In general, the findings presented in this chapter may have significant pedagogical implications for teachers and students of intercultural communication, but may also be of interest to those with a practical involvement in intercultural dialogue. Read more

The History And Context Of Chinese~Western Intercultural Marriage In Modern And Contemporary China (From 1840 To The 21st Century)

Table of Content

Abstract

Chapter One – Introduction

Chapter Two – An Intellectual Journey: The Theoretical Framework

Chapter Three – Mapping the Ethnographic Terrain: The Methodological Framework

Chapter Five – The Process of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage in Contemporary China

Chapter Six – Why do they marry Westerners? Motivations and Resource Exchanging in Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriages

Chapter Seven – Conflicts and Adjustments in Chinese-Western intercultural Marriage: A Cultural Explanation

Chapter Eight – Epilogue

Bibliography

Appendix I: Interview Questions Guide

Appendix II

Abstract

Intimate relationships between two people from different cultures generate a degree of excitement and intrigue within the couple due to that very difference, however this also brings its own challenges. Intercultural marriage adds an extra set of dynamics to relationships. Although the Chinese culture is very different from Western culture, individuals from both nevertheless meet and fall in love with each other. The existence of intercultural marriages and intimacy between Chinese and Westerners is evident and expanding in societies throughout both China and the Western world. This thesis aims to present a true picture of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage (CWIM) with a focus on the Chinese perspective.

By employing a three-dimensional, multi-level theoretical framework based on an integration of theories of migration, sociology and gender and adopting a qualitative research paradigm, the main body of this study combines three theoretical approaches in order to explore CWIM fully using a panoramic view. The first part of the study is conducted from a macro-level perspective. It provides a historical review of intercultural marriage and transnational marital systems in Chinese history from the modern to the contemporary era through a discussion of the different characteristics of CWIM. The context and background of Chinese intercultural marriages in modern and contemporary China are also reviewed and analysed, such as the related regulations, laws, governmental roles, and so on.

The second section is conducted from a middle-level perspective. On the basis of the study’s fieldwork, the demographic characteristics of the respondents are first disclosed, and different patterns are identified as occurring in CWIM. The approaches to and motivations of CWIM are examined, and a framework of CWIM Push-Pull Forces and a model of Resource Exchanging Layers are established to explain how and why Chinese people have married Westerners. The exchanges and Push-Pull force components operating in Chinese-Western intercultural marriages are also discussed.

The third section offers a micro-level examination of the research, and it moves on to discuss the family relations in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage, particularly with the entrance of a member of a different culture into the Chinese familial matrix. This part of the study focuses on cultural conflicts, origins and coping strategies in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage with an emphasis on the experiences of Chinese spouses. Five areas of marital conflicts are revealed and each area is analysed from a cultural perspective. The positive functions of conflicts in CWIMs are then explored. The six coping strategies and their frequencies of usage by Chinese spouses are further examined.

The final chapter will summarise the points examined previously and will unravel the factors underlying CWIM by recapitulating the symbolic significance, social functions and gender hegemony represented in Chinese-Western intercultural marriage. In this way this study will provide more than an anecdotal description of Chinese-Western Intercultural marriage, but will present a profound analysis of the forces underpinning this cross-cultural phenomenon.

Key Words: Chinese-Western Intercultural marriage, History, Cultures, Motivation, Exchange, Marital Choice, Conflicts.

List of Abbreviations

CCP – Chinese Communist Party

CCW – Chinese Civil War

CH – Chinese Husband

CPC – Communist Party of China

CHWW – Chinese husbands & Western wives

CW – Chinese Wife

CWIM – Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage

CWWH – Chinese wives & Western husbands

DIL – Daughter in Law

EU – European Union

FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FS – Foreign Spouses

IC – Intensity of Conflict

KMT – Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party)

LS – Local spouses

MIL – Mother in Law

MM – Marital Migrants

PRC – People’s Republic of China

ROC – Republic of China

TP – Third Parties Records

USSR – Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

VC – Violence of Conflict

CWWH – Marriage of Chinese Wife and Western Husband

CHWW – Marriage of Chinese Husband and Western Wife

WPA – Western Physique Attraction

The History And Context Of Chinese-Western Intercultural Marriage In Modern And Contemporary China (From 1840 To The 21st Century)

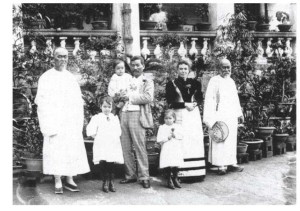

Australian wife Margaret and her Chinese husband Quong Tart and their three eldest children, 1894.

Source: Tart McEvoy papers, Society of Australian Genealogists

1.1 Brief Introduction

It is now becoming more and more common to see Chinese-Western intercultural couples in China and other countries. In the era of the global village, intercultural marriage between different races and nationalities is frequent. It brings happiness, but also sorrow, as there are both understandings and misunderstandings, as well as conflicts and integrations. With the reform of China and the continuous development, and improvement of China’s reputation internationally, many aspects of intercultural marriage have changed from ancient to contemporary times in China. Although marriage is a very private affair for the individuals who participate in it, it also reflects and connects with many complex factors such as economic development, culture differences, political backgrounds and transition of traditions, in both China and the Western world. As a result, an ordinary marriage between a Chinese person and a Westerner is actually an episode in a sociological grand narrative.

This paper reviews the history of Chinese-Western marriage in modern China from 1840 to 1949, and it reveals the history of the earliest Chinese marriages to Westerners at the beginning of China’s opening up. More Chinese men married Western wives at first, while later unions between Chinese wives and Western husbands outnumbered these. Four types of CWIMs in modern China were studied. Both Western and Chinese governments’ policies and attitudes towards Chinese-Western marriages in this period were also studied. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, from 1949 to 1978, for reasons of ideology, China was isolated from Western countries, but it still kept diplomatic relations with Socialist Countries, such as the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries. Consequently, more Chinese citizens married citizens of ex-Soviet and Eastern European Socialist Countries. Chinese people who married foreigners were usually either overseasstudents, or embassy and consulate or foreign trade staff. Since the economic reformation in the 1980s, China broke the blockade of Western countries, and also adjusted its own policies to open the country. Since then, international marriages have been increasing. Finally, this chapter discusses the economic, political and cultural contexts of intercultural marriage between Chinese and Westerners in the contemporary era.

1.2 Chinese-Western Intermarriage in Modern China: 1840–1949

In ancient China, there are three special forms of intercultural/interracial marriages. First, people living in a country subjected to war often married members of the winning side. For instance, in the Western Han Dynasty, Su Wu was detained by Xiongnu for nineteen years, and married and had children with the Xiongnu people. In the meantime, his friend Li Ling also married the daughter of Xiongnu’s King[i]; In the Eastern Han Dynasty, Cai Wenji was captured by Xiongnu and married Zuo Xian Wang and they had two children.[ii] The second example is the He Qin (allied marriage) between royal families in need of certain political or diplomatic relationships. The (He Qin) allied marriage is very typical and representative within the Han and Tang Dynasties. The third example is the intercultural/interracial marriages between residents of border areas and those in big cities. As to the former two ways of intercultural/ interracial marriage in Chinese history, the first one happened much more in relation to the common people plundered by the victorious nation, while the second one was an outer form of political alliance. The direct reason for the political allied marriage was to eliminate foreign invasion and keep peace. In that case, when the second form went smoothly, the first form inevitably ceased, however, when the first form increased, the second form failed due to the war. Read more