How Powerful Are The Remaining Royals?

07-20-2024 ~ Most royal families continue to face a decline in relevance, yet their ongoing efforts to adapt means they cannot be discounted entirely.

07-20-2024 ~ Most royal families continue to face a decline in relevance, yet their ongoing efforts to adapt means they cannot be discounted entirely.

Recently appointed British Prime Minister Keir Starmer pledged his loyalty to British King Charles III on July 6, 2024, continuing a tradition that dates back centuries. However, since the leadership role taken by Prime Minister David Lloyd George in World War I, the monarchy’s political influence has become progressively ceremonial and even more precarious since the death of the late Queen Elizabeth II in 2022.

This trend is not unique to the UK; in recent centuries, the role of royalty in politics has declined considerably worldwide. As political ideals began challenging royal authority in Europe, European colonial powers began to undermine their authority overseas. The strain of World War I helped cause several European monarchies to collapse, and World War II diminished their numbers further. After, the Soviet Union and the U.S. divided Europe along ideological lines and sought to impose their communist and liberal democratic ideals elsewhere, and the remaining monarchs faced accelerating marginalization.

Today, fewer than 30 royal families are politically active on a national scale. Some, like Japan’s and the UK’s, trace their lineages back more than a millennium, while Belgium’s is less than 200 years old. Several have adapted by reducing political power while maintaining cultural and financial relevance, while others have retained their strong political control. Their various methods and circumstances make it difficult to determine where royals may endure, collapse, or return.

Alongside the UK, the royals of Belgium, Spain, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands have all seen their powers become largely ceremonial. Smaller European monarchical states like Andorra and the Vatican City are not hereditary, while Luxembourg, Monaco, and Liechtenstein are—though only the latter two still wield tangible power. Read more

Sex Workers In Chile Continue To Face The Consequences Of COVID-19 Without Government Assistance

A little over a year ago, WHO declared the end of the COVID-19 health emergency. The pandemic had disastrous consequences for workers, especially those in the informal sector. According to a World Bank report, the last five years will reflect the lowest figures for economic growth in the last 30 years: 40 percent of low-income countries will remain poorer than they were before the pandemic.

A little over a year ago, WHO declared the end of the COVID-19 health emergency. The pandemic had disastrous consequences for workers, especially those in the informal sector. According to a World Bank report, the last five years will reflect the lowest figures for economic growth in the last 30 years: 40 percent of low-income countries will remain poorer than they were before the pandemic.

In Chile, 2 million jobs were lost during the pandemic. A report by the Economics Institute of the Catholic University of Chile indicates that the employment rate could only recover to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2026.

In this context, informal sector workers face an unaccounted crisis: the non-recognition of their work leaves them outside the ambit of adequate public policies for their recovery. As part of this sector, sex workers face the great limbo of the legal status of sex work in Chile: it is not prohibited, but it is not recognized as work either. Persecution is concentrated in the places where it is practiced. Herminda González, president of Fundación Margen, tells me that this option leaves only one option for the workers: the streets. From that place, the Fundación provides the assistance that the State does not provide.

The Solidarity Fund

During the quarantine, Herminda and Nancy Gutierréz (Margen’s spokesperson) took advantage of the early morning darkness to sneak into the Foundation’s headquarters, where they distributed boxes of food for the sex workers. “We did it because we knew the girls were waiting,” says Herminda. “And if it wasn’t us, who was going to do it? Only the people help the people.”

As the pandemic progressed, they decided to design protocols for safe sex. “Along with condoms, we distributed masks and latex gloves,” because, despite the restrictions, the work did not stop. “There were colleagues who earned a lot of money during the pandemic,” because obviously, the risk increased the value of the services. However, in any situation that meant not being able to work, the girls were completely unprotected, as they were not covered by any of the government schemes designed to protect workers recognized as such.

“Many of the sex workers support their families; they are mothers, daughters,” Gonzalez tells me. In the absence of the state—which only donated food to the foundation during the entire pandemic—“the aunts,” as the younger workers affectionately call the foundation’s leaders, decided to create a solidarity fund for sex workers, where allies and close clients made donations that allowed them to survive the pandemic crisis.

The Solidarity Fund is still active and is used to support sex workers during the hardest times of the year, including when it is time to buy school supplies, for example. Read more

Tariffs Don’t Protect Jobs. Don’t Be Fooled.

Richard D. Wolff

07-11-2024 ~ Both Trump and Biden imposed high tariffs on imported products made in China and other countries. Those impositions broke with and departed from the previous half century’s policies favoring “free trade” (less or minimal government intervention in international markets). Free trade policies facilitated “globalization,” the euphemism for the post-1970 surge in U.S. corporations’ investing abroad: producing and distributing there, re-locating operations there, and merging with foreign enterprises there. Presidents before Trump had insisted that free trade plus globalization best served U.S. interests. Both Democratic and Republican administrations had enthusiastically endorsed that insistence. Dutifully performing ideological support duties, they stressed how globalization’s benefits to U.S. corporations would “trickle down” to the rest of us. Globalizing U.S. corporations used portions of their profits to reward both parties with donations and other electoral and lobbying supports.

Our last two Presidents reversed that position. Against free trade they favored multiple government interventions in international trade, especially imposing and raising tariffs. Instead of advocating free trade and globalization, they promoted economic nationalism. Like their predecessors, Trump and Biden depended on financial support from corporate America as well as votes from the employee class. Many U.S. corporations and those they enriched had shifted their profit expectations in response to the competition they faced from new, powerful non-U.S. firms. The latter had emerged during the free-trade/globalization conditions after 1970, above all in China. U.S. firms increasingly welcomed or demanded protection from those competitors. Accordingly, they financed changes in the political winds and shifts in “public opinion” toward economic nationalism.

Trump and Biden thus endorsed pro-tariff policies that protected many corporations’ profits. Those policies also appealed to those for whom economic nationalism offered ideological comforts. For example, many in the United States grasped the relative decline of the United States and its G7 allies in the global economy and the relative rise of China and its BRICS allies. They welcomed an aggressive counteraction in the forms of tariff and trade wars. Both corporations (including mass media) and their subservient politicians worked to build popular and voter support. That was needed to pass the tax, budget, subsidy, tariff, and other laws that would realize the shift to economic nationalism. A key argument held that “tariffs protect jobs.” A political struggle pitted the defenders of “free trade” against those demanding “protection.” Over the last decade, those defenders have been losing. Read more

French Elections: What The Global Left Should Learn About Defeating The Far-Right

C.J. Polychroniou

07-11-204 ~ A united left is a formidable opponent that cannot only halt the surge of neo-fascism, but can also offer a positive and inspiring vision for the future.

Far-right forces have gained ground across Europe, particularly in Austria, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. In fact, the Netherlands has a new government, a coalition between far right and right, and the far right came first in the first-round of France’s snap election. But fearful of the prospect of a neo-fascist and xenophobic party in government, French voters came out in record numbers and rallied not behind Ensemble—the centrist coalition led by President Emmanuel Macron—but behind the coalition of left forces calling themselves the New Popular Front (NFP), delivering in the end a blow to Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (RN) which had made historic gains in the first round and topped the poll with 33.15 percent of the votes cast. NFP came in first in the run-off election, with 188 seats, but falling short of majority.

France’s snap parliamentary election results help us to make sense of the surge of the far right and offer valuable lessons for the left all over the world, including the U.S. where a centrist democrat and a wannabe dictator face off in November.

First, it is crystal clear that the main reason for the rise of Europe’s far right, authoritarian, and ethnonationalist forces is the status quo of neoliberal capitalism. The neoliberal counterrevolution that begun in the early 1980s and undermined every aspect of the social democracy model that had characterized European political economy since the end of the Second World War has unleashed utterly dangerous political forces that envision a return to a golden era of traditional values built around the idea of the nation by fomenting incessant and socially destructive change.

True to its actual aims and intent, neoliberalism has exacerbated capitalism’s tendency to concentrate wealth in the hands of fewer and fewer, reduced the well-being of the population through mass privatization and commercialization of public services, hijacked democracy, decreased the overall functionality of state agencies, and created a condition of permanent insecurity. Moreover, powerful global economic governance institutions—namely, the unholy trinity of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization—took control of the world economy and became instrumental in the spreading of neoliberalism by shaping and influencing the policies of national governments. It is under these conditions that ethnonationalism, racism, and neofascism resurfaced in Europe, and in fact all over the world.

In France, the rise of the far right coincided with President François Mitterand’s turn to austerity in the 1980s as his government fell prey to the monetarist-neoliberal ideology of the Anglo-Saxon world. Once Mitterand made his infamous neoliberal turn, the rest of the social democratic regimes in southern Europe (Greece under Andreas Papandreou, Italy under Bettino Craxi, Spain under Felipe Gonzalez, and Portugal under Mario Soares) tagged along, and the eclipse of progressivism was underway. Read more

The Sahel Stands Up And The World Must Pay Attention

Vijay Prashad

07-10-2024 ~ On July 6 and 7, the leaders of the three main countries in Africa’s Sahel region—just south of the Sahara Desert—met in Niamey, Niger, to deepen their Alliance of Sahel States (AES). This was the first summit of the three heads of state of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, who now constitute the Confederation of the AES. This was not a hasty decision, since it had been in the works since 2023 when the leaders and their associates held meetings in Bamako (Mali), Niamey (Niger), and Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso); in May 2024, in Niamey, the foreign ministers of the three countries had developed the elements of the Confederation. After meeting with General Abdourahmane Tiani (Niger), foreign minister Abdoulaye Diop (Mali) said in May, “We can consider very clearly today that the Confederation of the Alliance of Sahel States is born.”

There is a straight line that runs from the formation of this Confederation to the pan-African sentiments that shaped the anti-colonial movements in the Sahel over 60 years ago (with the line from the African Democratic Rally formed in 1946 led by Félix Houphouët-Boigny, and through the Sawaba party in Niger formed in 1954 and led by Djibo Bakary). In 1956, Bakary wrote that France, the old colonial ruler, needs to be told that the “overwhelming majority of the people” want their interests served and not to use the country’s resources “to satisfy desires for luxury and power.” To that end, Bakary noted, “We need to grapple with our problems by ourselves and for ourselves and have the will to solve them first on our own, later with the help of others, but always taking account of our African realities.” The promise of that earlier generation was not met, largely due to France’s continued interventions in preventing the political sovereignty of the region and in tightening its grip on the monetary policy of the Sahel. But the leaders—even those who were tied to Paris—continued to try and build platforms for regional integration, including in 1970 the Liptako-Gourma Authority to develop the energy and agricultural resources in the three countries. Read more

Photographers’ (Grand) Daughter

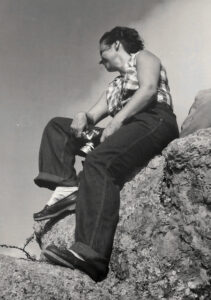

Photograph by Benjamin Gomes Casseres

Photography played a central role in the life of my family when I was growing up in Curaçao. This was certainly not the case for most others in the nineteen fifties and early sixties as it is today, when everyone carries a camera in their pocket and visual culture dominates our life. Then it was a matter of privilege that not many had.

Paíto, as we called my maternal grandfather Benjamin Gomes Casseres, began to photograph as a young man before 1910, and continued to do so throughout his life. Undoubtedly, he had the time and resources to devote himself to his passion of black and white photography. His many photo albums attest to his outstanding talent as an artist.

As the co-owner of a local camera store, my father, Frank Mendes Chumaceiro, and my mother, Tita Mendes Chumaceiro, had access to the latest equipment, allowing my father to become a pioneering cinematographer on the island, while my mother took color slides, having shifted her artistic talents from painting to photography. Through the years, she won many prizes with her color slides, and her photos of the island’s different flowers were chosen for a series of stamps of the Netherlands Antilles in 1955.

Together, my parents edited my father’s films into documentaries with soundtracks of music and narration and graphically designed titles and credits.

Sometimes these films were commissioned by various organizations and government institutions, including the documentation of visits by members of the Dutch royal family. Movie screenings were regularly held in our living room and at the houses of family and friends who would invite my parents to show their work, as well as at some public events. That was our entertainment in the nineteen fifties, long before television came to the island.

Both my brother Fred and I owned simple box cameras from a young age, working up to SLR cameras as we grew older. Still, I did not take photography seriously as an art until the digital age, when I began to feel I could finally have more control over my output. That was in 2005, when I got my first digital point- and-shoot camera, gradually professionalizing my equipment through the years.

My father and mother with their cameras on top of the Christoffel, 1956, photographer unknown

It was only recently that I began to think about the many ways my rich photographic lineage impacted my life and the directions I have taken as an artist, how it has influenced the development of my own photography. I have discerned six ways that account for this influence by my background – ranging from the circumstances in which the photographs were produced and viewed, to the attitudes that underlie the practice of photography as an art.

A. A treasure trove of photographs

Countless photo albums could be found in our home in Curaçao, with photos by both my parents in their younger years, and later by my brother and me.

After Paíto died in 1955, my mother inherited his albums with family photos, as well as albums with larger prints of his more artistic photographs. Paíto’s family albums documented his leaving Curaçao for Cuba with my grandmother in 1912, where he joined another member of the Curaçao Sephardic Jewish community in buying a sugar cane plantation, which seemed a good business opportunity that also sparked his adventurous spirit. Read more