Modern (Mis)interpretations Of Clean Slates

Michael Hudson

06-19-2024 ~ Today’s creditor-oriented ideology depicts the archaic past as much like our own world, as if civilization was developed by individuals thinking in terms of modern orthodoxy.

Why were Clean Slates so important to Bronze Age societies? From the third millennium in Mesopotamia, people were aware that debt pressures, if left to accumulate unchecked, would distort normal fiscal and landholding patterns to the detriment of the community. They perceived that debts grow autonomously under their own dynamic by the exponential curves of compound interest rather than adjusting themselves to reflect the ability of debtors to pay. This idea never has been accepted by modern economic doctrine, which assumes that disturbances are cured by automatically self-correcting market mechanisms. That assumption blocks discussion of what governments can do to prevent the debt overhead from destabilizing economies.

The Cosmological Dimension of Clean Slates

Mesopotamia’s concept of divine kingship was key to the practice of declaring Clean Slates. The prefatory passages of Babylonian edicts cited the ruler’s commitment to serve his city-god by promoting equity in the land. Myth and ritual were integrated with economic relations and were viewed as forming the natural order that rulers were charged with overseeing; in this context, canceling debts helped fulfill their sacred obligation to their city-gods. Commemorated by their year-names and often by foundation deposits in temples, these amnesties appear to have been proclaimed at a major festival, replete with rituals such as Babylon’s ruler raising a sacred torch to signal the renewal of the social cosmos in good order—what the Romanian historian Mircea Eliade called “the eternal return,” the idea of circular time that formed the context in which rulers restored an idealized status quo ante. By integrating debt annulments with social cosmology, the image of rulers restoring economic order was central to the archaic idea of justice and equity.

(Mis)Interpreting the Meaning of ‘Freedom’

The Hebrew word used for the Jubilee Year in Leviticus 25 is dêror, but not until cuneiform texts could be read was it recognized as cognate to Akkadian andurarum. Before the early meaning was clarified, the King James Version translated the relevant phrase as: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land, and to all the inhabitants thereof.” But the root meaning of andurarum is to move freely, as running water—or (for humans) as bondservants liberated to rejoin their families of origin.

The wide variety of modern interpretations of such key terms as Sumerianamargi, Akkadian andurarum and misharum, and Hurrian shudutu serve as an ideological Rorschach test reflecting the translator’s own beliefs. The earliest reading was by Francois Thureau-Dangin[1], who related the Sumerian term amargi to Akkadian andurarum and saw it as a debt cancellation. Ten years later Schorr (1915) related these acts to Solon’s seisachtheia, the “shedding of burdens” that annulled the debts of rural Athens in 594 BC. The Canadian scholar George Barton[2] translated Urukagina’s and Gudea’s use of the term amargi as “release,” although the Jesuit Anton Deimel[3] rendered it rather obscurely as “security.” Read more

A Historical Case For Why The EU Could Endure For More Than 1,000 Years

06-18-2024 ~ Empires historically possessed a unique ability to organize diversity and successfully rule over people quite different from one another. The national states that succeeded them in Europe were organized on the basis of nationality (real or imagined) where diversity in language, ethnicity, or religion was deemed a barrier to national unity. The negative consequences of celebrating unique national identities became clear after virulent nationalism led to the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II left Europe in ruins.

06-18-2024 ~ Empires historically possessed a unique ability to organize diversity and successfully rule over people quite different from one another. The national states that succeeded them in Europe were organized on the basis of nationality (real or imagined) where diversity in language, ethnicity, or religion was deemed a barrier to national unity. The negative consequences of celebrating unique national identities became clear after virulent nationalism led to the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II left Europe in ruins.

The European Union seeks to prevent this from happening again by restoring the cosmopolitanism, size, and economic clout of a multinational empire but without creating a unitary state in the process.

The EU is designed as a supranational polity where member states retain their national sovereignty and parochial identities but agree to be bound by its laws. They maintain their own armies, independent foreign policies, national parliaments and are free to leave if they so choose. The creation of such a chimeric political beast might appear unpreceded but it is not. The Holy Roman Empire successfully managed the affairs of central Europe by creating a similar composite political structure beginning in 962 under Otto I. In a bid to create unity in the German lands, where the Romans never ruled, the Holy Roman Empire proclaimed itself the successor to the long-dead Roman Empire as the defender of a Catholic Christian Europe. Lacking a single capital and imperial army, it did not seem to be much of an empire. However, its court system resolved disputes between member states, protecting the empire’s free cities and smaller estates (300+) against the more powerful ones. More unusually, it allowed individuals to seek redressals against local rulers who had violated their rights. Its Reichstag or Diet(legislature) met regularly to pass laws that were binding on all members and its emperorship was an elective position. That emperor’s power was limited because the estates within the empire remained responsible for governing their own territories. They were free to make alliances with outside powers as long as they were not detrimental to the empire or posed a danger to public peace.

That the Holy Roman Empire survived for 900 years suggests that it was on to something, and that the EU can be viewed as a secular reincarnation of it—minus only an emperor’s crown and Christian faith as symbols of its unity. However, other than making Charlemagne a symbol of European unity, it is a legacy that is largely unacknowledged and perhaps for good reason. Both the largely forgotten and derided Holy Roman Empire and the EU faced similar structural complexities and solved them in similar ways but the EU’s project was far more substantial—creating a polity that is now the world’s third-largest economy with a population of around 450 million people divided among 27 sovereign nations, which are spread across more than 4.2 million square kilometers. Read more

Migrating Workers Provide Wealth For The World

Vijay Prashad

06-18-2024 ~ Each year, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) releases its World Migration Report. Most of these reports are anodyne, pointing to a secular rise in migration during the period of neoliberalism. As states in the poorer parts of the world found themselves under assault from the Washington Consensus (cuts, privatization, and austerity), and as employment became more and more precarious, larger and larger numbers of people took to the road to find a way to sustain their families. That is why the IOM published its first World Migration Report in 2000, when it wrote that “it is estimated that there are more migrants in the world than ever before,” it was between 1985 and 1990, the IOM calculated, that the rate of growth of world migration (2.59 percent) outstripped the rate of growth of the world population (1.7 percent).

The neoliberal attack on government expenditure in poorer countries was a key driver of international migration. Even by 1990, it had become clear that the migrants had become an essential force in providing foreign exchange to their countries through increasing remittance payments to their families. By 2015, remittances—mostly by the international working class—outstripped the volume of Official Development Assistance (ODA) by three times and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). ODA is the aid money provided by states, whereas FDI is the investment money provided by private companies. For some countries, such as Mexico and the Philippines, remittance payments from working-class migrants prevented state bankruptcy. Read more

Can Teething Predict How Fast You Will Grow?

Brenna Hassett – Photo: en.wikipedia.org

06-17-2024 ~ We know that humans live relatively long lives, and we certainly know that we spend a larger proportion of those lives as children than other species. The question remains: how did we manage to extend this critical period of our growth? When and where did our ancestors start to stretch out the limits of physiology and build that long childhood? And where can we find evidence of this evolutionary process?

The very surprising answer is: in the mouths of babes—specifically, their teeth. But to understand how the timing of teeth tells us the story of, well, us, we need to first put teeth in context: as important milestones on the path to growth.

Different species grow at different rates. How fast you grow is determined by a complicated set of interlocking mechanisms that factor in everything from the mass of the animal to the stability of their environment and has led to the development of a branch of evolutionary biological theory that attempts to disentangle the factors that propel a species from one developmental milestone to the next: ‘life history.’ Understanding a species’ life history has major implications for biology: comparing the rate of growth between two species, for instance, gives us insight into different evolutionary strategies. For Homo sapiens, who have some of the slowest growth on the planet, looking at life history becomes a critical way to address why our species has moved our milestones so far from those of our nearest relatives. Read more

At Western Sahara: Visiting A Forgotten People

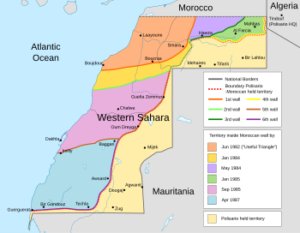

Western Sahara – Map: en.wikipedia.org

06-17-2024 ~ South of the Algerian town of Tindouf on the border with Western Sahara are five refugee camps. The camps are home to the Sahrawi people of Western Sahara and are administered by their freedom movement Polisario, which is fighting to liberate their homeland from Morocco.

Life in the desert camps leaves a deep impression and testifies to a people who, despite limitations, have managed to build a well-organized society under harsh conditions. “We Sahrawis were originally a nomadic people who used to travel around on camels and settled in different places in and around Western Sahara. There were no borders that limited us from moving into what is today Mauritania or Algeria,” said Jadiya who is a translator.

The colonial era saw European powers come to Africa to take over territories, exploit labor, and extract natural resources. In Western Sahara, the Portuguese and French were first beaten back by the local population before Spain managed to colonize the area in 1884. In 1973, the Polisario freedom movement was established by the indigenous Sahrawi people to liberate their land from the Spanish empire.

Western Sahara remained a Spanish colony until 1975 when the Moroccan government organized a so-called “Green March” with 350,000 protesters marching into Western Sahara to claim the land. The protesters pressured Spain to leave Western Sahara, which Morocco then occupied. Today, Western Sahara is still occupied by Morocco and is thus considered to be Africa’s last colony.

Desert Camps

It is around 35 to 40 degrees Celsius in Wilayah of Bojador, the smallest of the five refugee camps on the border with Western Sahara. My feet are boiling in my shoes, but walking in bare feet is not an option. The sand is far too hot. According to Filipe, a local Sahrawi engineer educated in the Soviet Union, it has been five to six years since it last rained in the camps. “Not a single drop from the sky,” he says. Read more

Rebuilding The Left Is Crucial To Stemming The Surge Of Europe’s Far Right

C.J. Polychroniou

06-12-2024 ~ Rebuilding the Left Is Crucial to Stemming the Surge of Europe’s Far Right.

Just over half of the 373 million citizens eligible to vote across the 27 European Union (EU) countries bothered to cast a ballot during the four-day European Parliament (EP) election that concluded on June 9. Germany — the EU’s most populous country, and its political and economic powerhouse but with its days as an industrial superpower rapidly coming to an end — saw a record-high voter turnout, with close to 65 percent of eligible voters turning out for the EP elections. Apparently, German citizens may have felt that the “business as usual” approach both in Brussels and inside their own country could no longer go on, which is why they dealt a humiliating defeat to the coalition government of Chancellor Olaf Scholtz. His ruling party, the Social Democrats, recorded their worst-ever result in EP elections, obtaining less than 14 percent of the vote. The conservatives — whose policies on immigration and climate have shifted close to the position of the far right on these issues — came in first, with over 30 percent of the vote, while the far right Alternative for Germany (AfD) came second by pulling 16.5 percent of the vote, up from 11 percent in 2019. The Green Party’s vote dropped by 8.5 percentage points, from 20.5 percent to 12 percent.

Undoubtedly, in Germany’s political and cultural environment today, anti-immigrant and anti-climate policies, and overall support for hardcore conservative and far right outlooks won.

By contrast, Greece, one of the EU’s peripheral countries, saw an explosive and unprecedented (by Greek standards) abstention rate, estimated to be around 60 percent. The ruling conservative party of New Democracy won the elections with 28.31 percent of the vote, taking seven seats, but suffered heavy losses (more than 1 million votes) from the last general elections. The once-radical Syriza party came second with 14.92 percent and four seats, while the social democratic PASOK came third with 12.79 percent and three seats. Greek Solution — an ultra-nationalist far right party which was created in the aftermath of Golden Dawn’s demise following its conviction for operating a criminal enterprise — came fourth with 9.3 percent and two seats, while another far right party, Niki, won 4.37 percent and one seat. The Communist Party received 9.25 percent of the vote and two seats. Read more