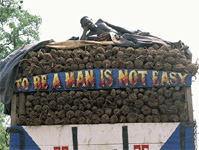

To Be A Man Is Not Easy ~ Stories From Ghanaian Emigrants. Contents & Introduction

Introduction – see below

1. The good samaritan who follows where the money is. Interview with Owusu Agyeman

2. Dollars in the wall. Interview with Mr. Babbs Haruna from Nkoranza

3. A scar reminds me of the day I wept. Interview with Kwame Baffo

4. My hotel! Interview with Michael Sarpong

5. The boys of the band. Interview with Akosua Asantewaah

6. Peace of mind or success? I want it both. Interview with Kojo Apiah Kubi. (Brian Osanhene Duako in Chicago)

7. It is love for one another that makes us continue. Interview with Kojo Sampson

8. I saw dead people covered in dust. passport on top. Interview with Mr. Darko from Nkoranza

9. No other treats than daily fresh insults. Interview with Yaw Charles from Nkoranza

10. I want to get a life but I cant because I am waiting. Interview with Richard Kwasi Ntim

11. Mercy, the girl with the red leggings

12. Education, solidarity and being able to say no. Interview with Matthew Essieh

13. Caught between two worlds. Interview with Samuel Oteng

14. The conference participant. Interview with Osei Takyi

Introduction

Why this book? It all started with Kwame Baffoe, the guy who only wept once. Kwame was the hospital driver at the time that I worked as a tropical doctor at Nkoranza Hospital. One day Baffoe disappeared. After two weeks his relatives came to ask for his end of service benefit. I was then the medical director as well as the administrator and I had to say No, he vacated his post so sorry, no. But where for God’s sake is Baffoe? They silently left. This was in the mid-eighties. Read more

To Be A Man Is Not Easy ~ The Good Samaritan Who Follows Where The Money Is. Interview With Owusu Agyeman

I am Owusu Agyeman and I come from from Akropong in the Nkoranza district. I live here in Nkoranza town where I have my well known Ash-foam business. I sell pillows and mattresses. As you may know, my father is a chief.

I am Owusu Agyeman and I come from from Akropong in the Nkoranza district. I live here in Nkoranza town where I have my well known Ash-foam business. I sell pillows and mattresses. As you may know, my father is a chief.

I decided to go to Libya because there is no work in Ghana. Let me correct myself and say it this way: there is work in Ghana but it doesn’t fetch any money. Take farming for example. I may use two million Cedis to prepare and sow the land and when I harvest my corn I may get 1,5 million in return. What does it mean? It means I lost. I have lost money because the market prices are bad. That is why I went abroad, to get enough money to start a business in Ghana.

At the time when I left Ghana I was no longer a young boy, I was thirty eight years old and had a wife and three children. My wife agreed that I should go in order to provide for the family. So then we had to prepare for such a journey which is both costly and dangerous. Danger is everywhere along the way but the walking, which we call footing, through the desert, that is the greatest risk! I will tell you the story of my journey. I started here in Nkoranza in Ghana and traveled in an ordinary lorry to the border at Bawku.

I then took a car across the border to Burkino Faso and then on to Mali. Finally I went deep into Niger where you reach the desert and then another chapter starts! Those days when I traveled there, there was no such thing as group transport with Ghanaians all the way to Libya. Not at that time. Now that has changed.

Africans need no visa on the West-African continent so I had all I needed which was my passport, my vaccination card and enough money. The last one is the hardest! At border crossings I of course never tell my real plans of going to Libya for they would send me right back. So at the Ghana border I say I go to Burkina Faso to work and from Burkina Faso I say I go to work at Mali. I have a profession. I am a mechanic. So that’s what I say: I am going to work there as a mechanic. Once in Mali they ask me where I am going and I say to Niamey in Niger. I went to Niamey and then to the second biggest city which is called Agadez. I did all this with ordinary local passenger cars. It is at Agadez that the story changes!

Here you have reached the desert. Here we sit and rest along the roadside and we wait. We wait for other people who are on their way to Libya. Once there are enough people to fill a car then you go across the desert. The cars are land-cruisers, pick-ups.

Niger is a poorer country than Ghana, no jobs. There are men there in Agadez who make a living out of assembling people and organizing a car for them. There are other men who make it their job to cross the desert with us and bring us to Libya. Two of these men sit in the cabin in front and all of us travelers are packed in the back of the pickup. In my case they took us, 90 to 100 persons, into two cars. At that time, 1997, they let us pay 20,000 CFA, which is about 50 dollar per person. We were packed like maize bags, sometimes they even got more than 50 people in one land-cruiser. Read more

The Postman Only Had To Ring Once

What a beautiful public love letter to an art that appears to be lost, but not quite. This writer, sharing his thoughts with who knows who, also longs for the intimacy of the exchange of words between two. What strikes me most about this essay are the words: “The day I lost one of J.’s illustrated postcards in the subway on my way home, I was as distraught as I would be now if my hard disk crashed.”

What a beautiful public love letter to an art that appears to be lost, but not quite. This writer, sharing his thoughts with who knows who, also longs for the intimacy of the exchange of words between two. What strikes me most about this essay are the words: “The day I lost one of J.’s illustrated postcards in the subway on my way home, I was as distraught as I would be now if my hard disk crashed.”

No, I would not say like “my hard disk” crashing. Not that at all. That least of all. That is an anxiety unique to this age of data-exchange, the reduction of all words, whether committed to hard-drive with care or hastily-strung-together, to an assemblage of giga-bytes. That feeling is equivalent to the boss berating you for losing an “important document”, no matter how important to you this hard-drive may be.

I have kept letters that are close to my heart, letters that mark milestones in my life and recollect those in the lives of those for whom I care, those who I remember, whether or not they remember me. I have lost some of these, in the jumble of our “modern” state of statelessness, placelessness. With each loss I knew I had lost a marker. Not that the object itself was a loss it itself. It was a loss because it has meaning in and of itself. The words, which were written with care and thought, sometimes in friendship, at times in love, are irreplaceable in a way that a hard-drive could never be. Letters brought more than news, or, rather, they defined a notion of news that many no longer regard as relevant. The postman only had to ring once.

Dropping these fragments in the subway would mean losing a piece of the dialogue that once existed, a fragment that could not have been spoken in words, and which cannot ever be committed to memory in the way that we can store passwords to social media sites, the literary equivalent of fifty shades of grey. Not even the spoken word can “reveal” itself in the immediacy of dialogue. We need to filter the maelstrom of spoken intonations, throw away thoughts, carelessly aimed barbs, fluff. In other words, we need to “process”, in the pseudo lingo of the day, as if the spoken word is something to receive like a legal brief, rather than to share in a collective act of interpretation.

So perhaps it is not only the written word that is fading, the medium for committing our most intimate thoughts. With that loss we risk losing the art of listening, rather than merely hearing as one does in a noisy room. We have turned listening into hearing, the ear into a portal to matter, and that extraordinary matter into a measurement of our relative sanity. Who has not heard the claim that we use perhaps 12-15% of our brains, “on average”? What better measure of our language of median lines. In this age of brain science thought, itself is losing its tragic quality, as we learn that the biological organ with which we think is also the locus of our deepest emotions, and we again take refuge in “spirit” to quell a fear inspired by our eternal finitude. Hang onto those letters and postcards. The brain has a sell-by date. The words it shapes into a personal declaration between two people do not.

About the author

Prof.dr. Anthony Court – Researcher, Genocide Studies, University of South Africa

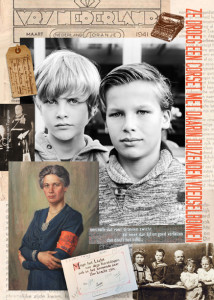

Het verhaal is nooit af… ~ Een korset met duizenden voedselbonnen

“Het is best heftig wat zich allemaal in mijn familie heeft afgespeeld. Mijn opa is Paul van Tongeren. Zijn vader Hermannus van Tongeren jr werd in 1944 met een nekschot doodgeschoten door de Duitsers vanwege zijn verzetswerk. Mijn opa is als tweejarige zijn vader kwijtgeraakt en zijn moeder was zo in shock dat ze niet meer heeft gesproken. Dat vind ik een heel naar verhaal”, vertelt de 12- jarige Sies van Tongeren in het Groningse Haren. Zijn broertje Mart (8 jaar) zit bij het gesprek.

De zuster van hun overgrootvader was Jacoba van Tongeren. Zij was zesendertig jaar toen de oorlog uitbrak en rolde via haar vader, Hermannus van Tongeren sr, generaal en grootmeester in de Orde der Vrijmetselaren, meteen het verzet in. Als oud-militair bracht hij haar militaire beginselen van geheimhouding bij. “Ze is door hem als een jongen opgevoed. Ze heeft als klein kind met hem in de bushbush gewoond in Nederlands-Indië, omdat haar moeder haar niet als kind wilde. Jacoba is waarschijnlijk de enige vrouw die tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog een grote verzetsgroep heeft geleid, Groep 2000. Ze was door haar vader getraind om sterk te zijn. Sommige mensen vonden het raar dat een vrouw leidster was van een groep. Maar ik beschouw haar als een stoere vrouw. Ze dacht aan anderen. Dat vind ik bijzonder.”

“Ze droeg een korset met daarin duizenden voedselbonnen. Ze deed net alsof ze zwanger was. De Duitsers stonden voor haar op.”

Groep 2000 werkte met een code die Jacoba van Tongeren had bedacht met het oog op veiligheid. Alle groepsleden, maar ook de vele onderduikers die zij ondersteunde, werden niet met hun eigen naam genoemd maar met een cijfercode. Ook het adres was gecodeerd. Alleen met een sleutel kon je de codes ontcijferen. Uiteindelijk liep het toch mis. Op vrijdag 9 maart 1945 werd het hoofdkantoor van Groep 2000 aan de Stadhouderskade 56 door de Duitsers bezet. Alhoewel Jacoba strikte orders had gegeven dat als er niet op kantoor werd gewerkt, de codesleutel meegenomen moest worden, bevond die zich toch nog op de Stadhouderskade toen de Duitsers er die vrijdagavond binnenvielen. Read more

Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN)

Founded in 1986, the Basic Income European Network (BIEN) aims to serve as a link between individuals and groups committed to, or interested in, basic income, i.e. an income unconditionally granted to all on an individual basis, without means test or work requirement, and to foster informed discussion on this topic throughout Europe.

Founded in 1986, the Basic Income European Network (BIEN) aims to serve as a link between individuals and groups committed to, or interested in, basic income, i.e. an income unconditionally granted to all on an individual basis, without means test or work requirement, and to foster informed discussion on this topic throughout Europe.

Members of BIEN include academics, students and social policy practitioners as well as people actively engaged in political, social and religious organisations. They vary in terms of disciplinary backgrounds and political affiliations no less than in terms of age and citizenship. In the course of two decades, “BIEN” has become somewhat of a misnomer, as scholars and activists from other continents have actively joined the network.

Common to all is the belief that some sort of economic right based upon citizenship – rather than upon one’s relationship to the production process or one’s family status – is called for as part of the just solution to social problems in advanced societies. Basic Income, conceived as a universal and unconditional, if modest, continuous stream of income granted throughout life to all members of a political community is just the simplest and most striking element in an expanding set of social policy proposals inspired by this belief and currently debated, if not already implemented.

To actively foster this debate, BIEN publishes a newsletter which provides an up-to-date and comprehensive international overview on relevant events and publications. It organises bi-annual BIEN-congresses where people from more than twenty countries have met to report and discuss basic income and related proposals in connection with a broad spectrum of themes, such as unemployment, European integration, poverty, development, changing patterns of work career and family life, and principles of social justice.

BIEN expanded its scope from European to the Earth in 2004. It is an international network that serves as a link between individuals and groups committed to or interested in basic income, and fosters informed discussion of the topic throughout the world.

Go to: http://www.basicincome.org/

National Anthropological Archives

The National Anthropological Archives and Human Studies Film Archives collect and preserve historical and contemporary anthropological materials that document the world’s cultures and the history of anthropology. Their collections represent the four fields of anthropology – ethnology, linguistics, archaeology, and physical anthropology – and include fieldnotes, journals, manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, maps, sound recordings, film and video created by Smithsonian anthropologists and other preeminent scholars.

The collections include the Smithsonian’s earliest attempts to document North American Indian cultures (begun in 1846 under Secretary Joseph Henry) and the research reports and records of the Bureau of American Ethnology (1879-1964), the U.S. National Museum’s Divisions of Ethnology and Physical Anthropology, and the River Basin Surveys. The NAA also maintains the records of the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology and of 25 professional organizations, including the American Anthropological Association, the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, the American Ethnological Society, and the Society for American Archaeology.

Enjoy: http://www.anthropology.si.edu/