The Dutch Party for Freedom. An Analysis of Geert Wilders’ Thinking on Islam

In The Dutch Party for Freedom. An Analysis of Geert Wilders’ Thinking on Islam (Previously published as The Speck In Your Brother’s Eye), Jan Jaap de Ruiter analyses Marked for Death. Islam’s War Against The West and Me writtten by Geert Wilders, leader of the Dutch Freedom Party.

‘The solution Wilders presents involves a high risk of invoking violence, even if he states repeatedly that his program should be realized by the word and the pen. Who will give me the assurance that this would indeed be the case? Who can guarantee us that there will not be people who, like so many Christians, Muslims and French revolutionaries, will take up the sword and ‘help’ to realize their goals that way? Wilders’ book brings us nothing new. Not only that, it is also completely counter- productive. Wilders’ message is not like that of religions and ideologies, which not only have a negative but also a positive side. It is exclusively negative. He focuses on the shortcomings of the other, accuses the other of being violent by nature, and uses words that can easily be interpreted as allowing violence to fight the enemy. He acts in exactly the same way as he perceives his opponent does. He sees the speck in his brother’s eye but fails to see the log in his own.

It may very well be the case that Geert Wilders will in due time give up his position as leader of the Freedom Party and leave the Dutch political arena. He might indeed, as was suggested, join an American think tank or travel the world spreading the message of the danger of Islam. Irrespective of where his career leads him, this will not mean that the anti Islam discourse will die out. On the contrary, it is supported by numerous others and in particular on the Internet it is very strong. Therefore countering this ideology by arguments, by pamphlets like this, remains necessary.

‘Am I showing myself to be a reprehensible cultural relativist here?’, asks De Ruiter in one of the chapters. ‘Undoubtedly’, is his answer.’

The Dutch Party for Freedom. An Analysis of Geert Wilders’ Thinking on Islam now online:

Chapter One – Wartime

Chapter Two – Truth

Chapter Three – Culture

Chapter Four – Ideology

Chapter Five – Solution

Chapter Six – The Speck In Your Brother’s Eye

Norman White – But I would prefer that it sneaks in through some back door

The Normill is an old watermill in Durham (Ontario, Canada), a village 80 miles Northwest of Toronto. The big stone building next to a stunningly beautiful pond, was bought years ago by artist Norman T White (San Antonio, Texas, 1938)

The mill smells like old flour, animal carcasses and bat shit and harbours the soul of Norman White. His personal history is visible in the old photos of the Dutch fisherman relatives of his mother. The building is littered with the material his work is made of: machine parts and a bunch of old computers. The raw architecture of the construction seems hardly altered in the years White lived in it. He sleeps over the gas stove in the kitchen in a small attic. The reason why he lodges here lies in the cold winters, when snow piles up and the temperature drops below zero. The building is spacious: it has a clean working spot; a big storage space, a cellar, actually a steel workshop; a room full of closets and drawers stacked with electronics; enough room for a large bat colony that lives in the cracks in the impressive walls.

You can walk around for hours, investigate the archives, the boxes with machine parts and printed circuit boards, wired art pieces in themselves. In the corner of the cellar leans a big raft made of plastic bottles against the wall.

Norman White, in his seventies, looks young: more a boy then a man. His friends say that his looks never changed, he is the same as thirty years ago. White is a myth in and outside of Canada. He is one of the godfathers of electronic-, machine- and robotic art and taught for more then twenty five years at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto. His offspring is well known in the electronic art world, Doug Back, Peter Flemming, Jeff Man, Graham Smith and David Rokeby are his former students. And they all visit his annual parties at the Normill, to celebrate their friendship with fires, swimming, music and art. Regularly artists from all over the world join and camp at the mill. White and his friends organised robot fights, machine wrestling: ‘Rawbotics & Sumo robots’ long before it became fashionable. Read more

What Will Be The Long-Term Development Of The Population Of The German Reich After The First World War? – Introduction and Abstract

General Introduction

The 1920’s and 1930’s are among the most interesting periods in the history of modelling and forecasting. The continuous decline of Western birth rates in the inter-war period set alarm bells ringing. Concerns about the future size and growth of the populations of these nations were heightened by long-term extrapolations of time series, and by population projections and population forecasts. Concerns turned to acute anxiety after it became to appear that the leading Western European nations would not replace their populations. The imminent population decrease threatened to diminish the relative power of what were called in those days the ‘civilized’ nations and ultimaltely to result in ‘race suicide’ (the extinction of populations).

In some countries statisticians, demographers, or economists developed population projection methodology in order to free current debates on the population issue from emotional, subjective argument. In the two leading Fascist countries – but in other countries as well – population numbers were seen as the key to economic, political and military strenght. Read more

Wie wird sich die Bevölkerung des Deutschen Reiches langfristig nach dem Erstem Weltkrieg entwickeln?

Die ersten amtlichen Bevölkerungsvorausberechnungen in den 1920er Jahren.

Problemstellung

Nach dem Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs rückten die demografischen Veränderungen in den Kriegs- und Nachkriegsjahren in das Zentrum der öffentlichen Debatten. Gegenstand statistischer Analysen bildeten die Geburtenausfälle in den Jahren 1914 bis 1919, die Übersterblichkeit der männlichen Bevölkerung und die Entstehung des Frauenüberschusses, die den Altersaufbau der Reichsbevölkerung nach dem Weltkrieg prägten. Hinzu kamen die Bevölkerungsverluste, die aus der territorialen Neugliederung des Deutschen Reichs in Folge der Umsetzung des Friedensvertrages von Versailles entstanden.1 Das Statistische Reichsamt stellte sich zur Aufgabe, die Verwerfungen in der Alters- und Geschlechtsstruktur als auch die bereits vor dem Weltkrieg eintretenden Veränderungen im Geburtenverhalten zu untersuchen und deren langfristige Auswirkungen auf die Bevölkerungsdynamik zu berechnen. Binnen vier Jahren erstellte das Statistische Reichsamt zwei demografische Vorausberechnungen über die künftige Bevölkerungsentwicklung und -struktur für das Territorium des Deutschen Reiches nach 19192 (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 316, 1926 und Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 401, II, 1930). Die Grundlage für diese ersten zwei amtlichen Vorausberechnungen boten die Ergebnisse der Volkszählungen der Jahre 1910, 1919 und 1925.

Es wurden weitere statistische Erhebungen und Ergebnisse zur natürlichen Bevölkerungsbewegung im Deutschen Reichsterritorium nach dem Erstem Weltkrieg hinzugenommen (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 276, 1922; Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, 316, 1926; Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, Sonderhefte zu Wirtschaft + Statistik, 5, 1929, Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 360, 1930, Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, 401, I +II, 1930).

In der ersten 1926 erschienenen Vorausberechnung wurde die Entwicklung der Bevölkerungsdynamik und -struktur für einen Zeitraum von 50 Jahren (1925 bis 1975) und in der zweiten, 1930 erschienen, für einen Zeitraum von 75 Jahren (1930 bis 2000) und darüber hinaus erstellt.3 Nahe zeitgleich hier zu erarbeitete der Bevölkerungsstatistiker Friedrich Burgdörfer (1890-1967) eine weitere demografische Vorausberechnung.4 Read more

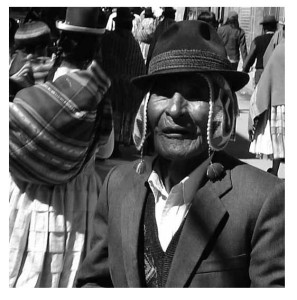

Van yatiri tot privékliniek – Interculturaliteit in de gezondheidszorg in Bolivia – deel 1

Toegang tot goede gezondheidszorg is een belangrijke basisbehoefte. Maar wat is goede gezondheidszorg? Als wij in Nederland ziek worden, hebben we er in de meeste gevallen wel vertrouwen in dat onze huisarts of een specialist in het ziekenhuis ons weer geneest. We begrijpen min of meer hoe het zorgsysteem in elkaar steekt, en hoeven ons over de kosten van de behandeling nauwelijks zorgen te maken omdat we verzekerd zijn. Als we in het buitenland zijn, wordt de situatie al lastiger. De arts spreekt onze taal niet en we weten niet hoe het systeem werkt. Hetzelfde geldt natuurlijk voor immigranten in Nederland die het Nederlands nog niet goed beheersen.

Dit soort problemen speelt ook in andere landen met een cultureel diverse bevolking. Voor de inheemse inwoners van ontwikkelingslanden kan het Westerse zorgsysteem vreemd, onbegrijpelijk en angstaanjagend overkomen. In veel gevallen vertrouwen zij liever op hun eigen inheemse geneeskunde, vaak uitgevoerd door medicijnmannen en -vrouwen. Read more

Van yatiri tot privékliniek – Interculturaliteit in de gezondheidszorg in Bolivia – deel 2

4. El Alto: Capital Andina

Net als dat Bolivia een bijzonder land is, is El Alto een bijzondere stad in Bolivia. Oorspronkelijk is El Alto ontstaan als een sloppenwijk van La Paz. La Paz ligt in een dal naast de hoogvlakte. Toen het dal van La Paz vol raakte, is de stad letterlijk ‘over de rand’ gekropen, de hoogvlakte op.

Van sloppenwijk tot miljoenenstad

De bevolkingsgroei in deze sloppenwijk nam een vlucht na de Nationale Revolutie van 1952. De hierin afgedwongen landhervormingen zorgden ervoor dat kleine boeren niet langer konden overleven van de landbouw (Kranenburg 2002). Deze voornamelijk inheemse (Aymara) boeren hoopten op een beter leven in de stad en kwamen in El Alto terecht, wat ook weer andere migranten van Aymara afkomst aantrok. Zij voelden zich het meest thuis in deze stad waar ook hun eigen inheemse en plattelandstradities behouden bleven (Muriel Hernandez 1995). Nadat in de jaren ’80 veel mijnen sloten, trokken ook de voornamelijk Quechua mijnwerkers naar El Alto (Kranenburg 2002). In 1985 werd de wijk een onafhankelijke gemeente. Bijna alle inwoners van El Alto (alteños) komen van de hoogvlakte, en dan niet alleen uit Bolivia maar zelfs een deel uit Peru. Ook voor deze inheemse Peruanen is de culturele overgang van hun dorp naar El Alto kleiner dan naar bijvoorbeeld de Peruaanse hoofdstad Lima. Migranten uit andere delen van Bolivia zijn er eigenlijk nauwelijks, al neemt de laatste jaren het aantal migranten uit La Paz toe. Zij ontvluchten de dure woningmarkt van La Paz. Inmiddels wonen er naar schatting tegen de één miljoen mensen in El Alto. Hiermee is het de grootste stad op de hoogvlakte en ze wordt dan ook wel ‘Capital Andina’ genoemd (van Rijn 2006).

Ondanks dat in Bolivia stedelijke gebieden gemiddeld rijker zijn dan het platteland, leeft tweederde van de inwoners van El Alto onder de armoedegrens. Nog eens 17% leeft in extreme armoede. Dit is lager dan het nationale gemiddelde. Basisbehoeften zoals sanitaire voorzieningen, onderwijs en toegang tot zorg worden niet vervuld (INE 2005). Veel huizen, vooral in de nieuwere wijken aan de rand van de stad, hebben nog geen goede sanitaire voorzieningen, al wordt hier wel aan gewerkt door de gemeente (van Rijn 2006). Read more