ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Refuting Counter-Arguments In Written Essays

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Many discourse analysts and rhetoricians have noted that one valued basis for argumentation, and academic argumentation, in particular, is contrast, that is, setting out opposition (Barton 1993; 1995; Peck MacDonald 1987).

The aim of this paper is to look more closely into one specific type of contrast and describe its structures and usage. The contrast I have in mind is the refutation of counter-arguments, defined as arguments (i. e., reasons) in favor of the standpoint (the conclusion) opposite to writer’s own standpoint. In order to see how writers actually refute counterarguments, I chose a book called Debating Affirmative Action: Race Gender, Ethnicity, and the Politics of Inclusion, edited by Nicolaus Mills 1994. The book is mostly a collection of argumentative texts by academic scholars, which debate a well defined issue, and clearly and unequivocally pronounce themselves most of the time either pro or con affirmative action. In less than 200 pages (not all the 307 pages of the book are argumentative texts), about 130 counter-argument refutations have been found. These texts are enough to give us a good idea about the most popular ways of refuting counter-arguments in written texts when debating controversial political or social issues in an academic milieu.

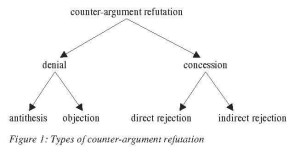

A counter-argument can be refuted in two possible ways:

1. by denying the truthfulness or the acceptability of the propositional content of the counter-argument, thereby denying its value as counterargument;

2. by accepting the truthfulness of the propositional content of the counter-argument, but, nevertheless, rejecting the opposite standpoint and therefore denying the relevancy or the sufficiency of the proposition to serve as counter-argument. The first type will be called denial, the second concession (see Perelman 1969: 489; Henkemans 1992: 143-153).

Two subtypes of denial have been discerned:

1. when the denied proposition is replaced by another, which serves as a pro-argument, or is argumentatively neutral;

2. when the denied proposition is not replaced by another. The first subtype will be called antithesis (the proposition that has been denied is the ‘thesis’, and the one replacing it is the ‘antithesis’), the second objection.

Concession also has been classified into two sub-types:

1. when the rejection of the opposite standpoint is directly made and in plain words (direct-rejection concession);

2. when it is only implied (indirect-rejection concession) (see also Azar 1997). Figure 1 summarizes this classification:

We will see now in further detail, together with examples, the four subtypes of Counter-argument refutation.

2. Antithesis

Antithesis is by definition a two-part structure, one expressing explicit denial of a proposition (in our case it is the denial of the counterargument) the other expressing an assertion (in our case it serves as a pro-argument) In our limited corpus, one can find that the denial part of the antithesis always precedes the other part. Only few example have been found, i. e.,

1. Far from preventing another Mount Pleasant (a Washington DC neighborhood where a three- day riot was sparked when a black policeman shot a Salvadoran man – M.A.), affirmative action might actually provoke one (p. 178).

The linguistic devices expressing antithesis consist of many forms. In our example it is far from … actually … .The more usual expression, not … but …, has not been found in our corpus as expressing antithesis; instead, we find: not X Y; not X Rather Y; X Such is the silliness … Y. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Arguing Over Values: The Affirmative Action Debate And Public Ethics

1. Purpose and Rational

1. Purpose and Rational

It has long been recognized that public values are inculcated through the stories and myths revealed in public discourse (see, for example, Cassirer 1944 and Eliade 1963). One story, especially pervasive in western societies, is the “rags to riches” phenomenon.

According to this narrative, known in the United States as the American Dream, individuals could, through their own determination, skill, or happenstance, overcome the circumstances of their birth and achieve greatness. This myth was exemplified in the nineteenth century stories of Horatio Alger.

Until the 1960s, in the United States, this narrative, with rare exception, was limited to white males. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 through its prohibition of discrimination eliminated many structural barriers to equal participation. But the removal of discrimination alone would not enable all Americans to compete equally. Some individuals came to competition hobbled by years of racism. Thus, a policy of Affirmative Action evolved. Affirmative Action established the requirement that government, and those who do business with the government, act affirmatively to recruit and promote women and minorities in order to foster equal participation in the American Dream. For three decades Affirmative Action, in varying incarnations, was the law of the land and resulted in significant changes in employment demographics. It also led to a backlash principally among arch conservatives and white males who claimed to suffer from “reverse discrimination.”

In 1996, voters in the state of California overwhelmingly supported a state ballot initiative, Proposition 209, which abolished Affirmative Action in state employment and education. In California such propositions, if passed by a majority, become law. Somewhat surprisingly, one in four minority voters and one out of two woman cast their ballots to eliminate the very programs established for their benefit. Leaders in other states began similar initiatives and federal lawmakers moved to enact comparable national legislation. Other anti-Affirmative Action activists continued to pursue judicial relief. Civil Rights leaders warned that elimination of preferences would significantly and adversely affect employment and educational opportunities for minorities.

This essay examines the remarkable and politically incendiary debate over Affirmative Action in the US. More specifically, representative anecdotes of the main public argumentation over the debate to abolish Affirmative Action will be analyzed to determine its nature and the implications it may have on race relations, public values, and notions of community. Such an inquiry is warranted for several reasons.

First, the Affirmative Action debate touches “the raw nerves of race, gender, and class – all of which are flash points of social debate and so emotionally charged that they beg for rational discussion and analysis” (Beckwith & Jones 1997: backflap).

Second, the public affirmation of legislation reveals public values. Anti-Affirmative Action argumentation began with reactionaries, was subsumed by conservatives and is now voiced by some liberals. Understanding the core values behind these shifting values reveal new conceptions of the “public” and “community” are therefore of interest to argument scholars in that they inform us as to how cultural narratives shape or fail to shape discourse in the public forum. Finally, while Affirmative Action may be a uniquely American program, how cultures cope with the diversity of their populace is an issue many nations must address. In Europe, in particular, many are struggling with issues of discrimination and segmentalism. Argumentation scholarship serves a useful public function if it can inform these debates through analog to what is transpiring in the US. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – The Function Of Argumentation Dialogue In Cooperative Problem-Solving

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The aim of the research described in this paper is to understand the functional role of argumentation dialogue in cooperative problem-solving, and ultimately, to understand how argumentation can give rise to cooperative learning. By cooperative learning, we mean the type of learning that occurs specifically in virtue of cooperation between people in performing some activity. We propose refinements of known cooperative learning mechanisms on the basis of analyses of cognitive-interactive processes that are at work in argumentation dialogues, for the specific case of a corpus of cooperative problem-solving dialogues in the domain of school physics problem-solving.

Firstly, the study of argumentation dialogue is situated within recent tendencies in cooperative learning research. Then three hypotheses concerning the way in which argumentation dialogue could lead to cooperative learning are discussed: knowledge explicitation, attitude revision and co-elaboration of meaning in relation to conceptual change. An approach to analysing the extent to which these mechanisms are at work in argumentation dialogue is proposed, based on five interrelated dimensions: dialectical, rhetorical, epistemological, conceptual and interactive. Results of analysing these dimensions in a specific corpus are summarised. The analyses reveal the relations between participants’ reasoning and the types of knowledge expressed during argumentation, the way in which argumentation outcomes function with respect to changes in attitudes, and the argumentative contexts in which meaning is co-elaborated and conceptual change occurs.

2. The study of verbal interaction in cooperative learning research

During the last decade, the efforts of many researchers have been directed towards identifying specific forms and phenomena of verbal interactions between learners that correlate with learning effects, under certain specific conditions. This interactions paradigm (Dillenbourg, Baker, Blaye & O’Malley 1996) can be represented as follows : conditions -> interactions -> effects [“->” symbolises causality]. However, when one considers real cooperative learning situations, that usually extend in time over an hour or more, this linear schema turns out to be too simple.

Firstly, once learners become more competent at solving a given type of problem, and they have learned how to cooperate together better, then the form of their interaction usually changes (i.e. there is a backward arrow from effects to interactions).

Secondly, what is important for explaining learners’ activity is not so much the set of objective conditions, but rather the way in which these conditions are understood by the subjects themselves. There is thus also a backward arrow from interactions to conditions, to the extent that subjects’ understanding of the problem-solving situation is continually negotiated during verbal interaction. Given these facts, it is difficult to use existing quite general (neo-Piagetian and Vygotskian) theories of cooperative learning, that have often relied on a simple distinction between cooperation and conflict, in order to identify the precise interactional phenomena that can be correlated statistically with learning effects. What is required is the development of more specific and local models of cooperative learning (Mandl & Renkl 1992) that will enable us to understand how three types of processes interact dynamically: dialogue, cooperation and problem-solving. Cooperative learning will then be viewed as emerging from the complex interaction of these three processes. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – ‘The Search For Grounds In Legal Argumentation: A Rhetorical Analysis Of Texas v. Johnson’

Legal opinions are essentially rhetorical documents: they pronounce a decision then justify that decision through a series of arguments aimed at particular audiences. Although law has often been held up as an archetype of practical argument, legal arguments must adhere to a stricter level of scrutiny then many other types of argument. Court decisions, particularly those made by the Supreme Court, are analyzed by a variety of experts, some of who have direct influence on the argument as it is being constructed (Golden and Makau, 1982: 172). These audiences constrain the possible means of persuasion which may be incorporated into the argument.

Legal opinions are essentially rhetorical documents: they pronounce a decision then justify that decision through a series of arguments aimed at particular audiences. Although law has often been held up as an archetype of practical argument, legal arguments must adhere to a stricter level of scrutiny then many other types of argument. Court decisions, particularly those made by the Supreme Court, are analyzed by a variety of experts, some of who have direct influence on the argument as it is being constructed (Golden and Makau, 1982: 172). These audiences constrain the possible means of persuasion which may be incorporated into the argument.

These constraints serve to limit the types of arguments which may be made in a case, the types of evidence which may be used to support the argument, and the very form that the argument may take. Despite these restrictions, legal argument is dynamic; new arguments are made and accepted, the law changes over time.

Legal argumentation covers a wide variety of issues. Each issue has a different set of questions which must be addressed by the Court when it announces a decision. Free speech cases provide a limited set of non-legal concepts which the judge may integrate into the decision. These concepts include the speaker, the speech and the audiece of the speech. These become the materials which the judge may use to overcome the constraints set on the decision by the audience. In this paper, I will examine how the Court uses the construct of audience in the Texas v Johnson case. This case reveals how dynamic legal argumentation can be, even given the strict constraints the Supreme Court must operate under.

1. Developing a Theory of Constraints

Court documents are constrained by the expectations of the audience. These constraints are not formally codified; they exist in the author’s conception of the expectations of this audience. The audience judges the correctness of a justice’s interpretation of the law, and this judgment is internalized by the author of the opinion.

James Boyd White notes, “In every opinion a court not only resolves a particular dispute one way or another, but validates or authorizes one kind of reasoning, one kind of response to argument, one way of looking at the world and at its own authority, or another” (1988: 394).

Stare decisis is the most pressing constraint on a Supreme Court judge. Golden and Makau note, “Use of stare decisis gives the court’s readers greater confidence in the Justices’ impartiality” (Golden and Makau 1982: 160).

The tapestry of the law forms the backdrop for the finding of any particular case. The author of an opinion must weave his or her finding into the cloth in such a way as not to radically disrupt the patterns which the audience has come to expect for the type of case being decided. These patterns consist of the materials which a justice may use to justify the opinion including the constitution, state law, and prior court cases. Stanley Fish provides an excellent example of a decision which would be considered a break from the pattern of the law, “A judge who decided a case on the basis of whether or not the defendant had red hair would not be striking out in a new direction; he would simply not be acting as a judge, because he could give no reasons for his decision that would be seen as reasons by competent members of the legal community” (1989: 193). Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – What Are The ‘Anarchical Fallacies’ Jeremy Bentham Discovered In The 1789 French: Declaration Of The Rights Of Man And Citizen?

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The year 1998 deserves to be remembered for at least two different but convergent reasons. In 1748 – two and a half centuries ago – Jeremy Bentham was born in London, and half a century ago – in 1948 – the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York. Thus this year we celebrate both the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the birth of a major English philosopher, lawyer, reformer, and public policy analyst; and we also celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the most influential manifesto of international human rights.

The conjunction of these two events provides an occasion for reflection on some of Bentham’s views because he wrote an essay titled “Anarchical Fallacies” in which he attacked the most popular manifesto of human rights in his day, the 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. In light of Bentham’s scathing criticisms of the French Declaration, one naturally wonders what he would have had to say today were he in a position to evaluate the United Nations Declaration. Would he say of it what he said of its French predecessor, that it consists of “execrable trash,” that its purpose is “resistance to all laws” and “insurrection,” that its advocates “sow the seeds of anarchy broad-cast,” and, most memorably, that any doctrine of “natural rights is simple nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense, – nonsense upon stilts”?

2. Dubious Fallacies

Let us look more closely at Bentham’s argument that the French Declaration is riddled with “anarchical fallacies.” What, exactly, are “anarchical fallacies”? What is fallacious and what is anarchistic about them?

In 1824, more than two decades after he had written his essay on “anarchical fallacies,” Bentham arranged with some of his younger friends to publish (in London and in English) a volume called The Book of Fallacies. In this treatise, the first substantial contribution to the subject since Aristotle, Bentham set out an account of what he regarded as the rhetorical and logical errors to which political discourse was especially vulnerable. One would naturally expect, therefore, to find in this book an elucidation of the “anarchical fallacies” he had already discussed many years earlier in his essay of that name. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Metaphorical Politics: Mobilization Or Tranquilization?

Politicians tend to express themselves indirectly. Sometimes they do so because they live in a totalitarian society, in which free expression is prohibited. Political crisis and war or severe economic crisis also affect directness and explicitness of political rhetoric. Politicians in prosperous democratic society, however, also see advantages in indirect or non-literal linguistic strategies. Commercialization of society, media, and politics reinforce this trend. Floating voters form an increasing segment of the electorate and politicians want to attract these voters by means of indirect statements with limited political content.

Politicians tend to express themselves indirectly. Sometimes they do so because they live in a totalitarian society, in which free expression is prohibited. Political crisis and war or severe economic crisis also affect directness and explicitness of political rhetoric. Politicians in prosperous democratic society, however, also see advantages in indirect or non-literal linguistic strategies. Commercialization of society, media, and politics reinforce this trend. Floating voters form an increasing segment of the electorate and politicians want to attract these voters by means of indirect statements with limited political content.

Metaphors are a form of indirect communication that has many advantages for politicians who know how to use them and when. Why is it that metaphors are essential to political rhetoric and mass communication? What does metaphorical reasoning include? How do politicians use metaphorical reasoning? How do social scientists deal with the study of metaphors in politics?

1. Metaphorical Reasoning and Cognitive Blending

Contemporary theory and research in cognitive science have widened scientific interest in metaphors, a literary device with ancient roots. Cognitive schema theory suggests that the mind generates virtual simulations, similar to computer software programs that interpret the physical world. Appropriate external stimuli activate these internal schemata, which help us understand and react. Human action and reaction are thus mediated by schema-driven cognition. Metaphors reflect and drive these schemata. Metaphor is thus both a facet of language and a dimension of cognition.

According to traditional Aristotelian theory, metaphors were linguistic phenomena that included the substitution of one word for another. The Oxford English Dictionary seems to follow this path when it defines metaphor as “the figure of speech in which a name or descriptive term is transferred to some object of different form, but analogous to, that to which it is properly applicable” (OED 2).

Going beyond this, modern metaphorical theory has created terminology to denominate elements of the metaphorical expression. In this lexicon,(A) is the topic, tenor, or target, the ground, which is the actual subject of discussion; (B) is the source or vehicle, which is an idea from a different sphere of life, which is literally used to describe the subject (A); between (A) and (B) exists a blended space producing tension (C). The interaction between these two ideas (A) and (B) generates a new, figurative, blended meaning (C), and a new view upon the subject. Older theories of metaphorical comparison and substitution neglect (C), the value added by the fusion of (A) and (B), which is at the core of the interaction theory (Turner and Fauconnier, 1995; Lakoff and Turner 1989; Ortony, 1984). Read more