Is This The End Of French Neo-Colonialism In Africa?

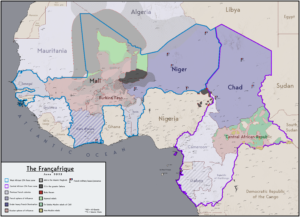

Françafrique – en.wikipedia.org

In Bamako, Mali, on September 16, the governments of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger created the Alliance of Sahel States (AES). On X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, Colonel Assimi Goïta, the head of the transitional government of Mali, wrote that the Liptako-Gourma Charter which created the AES would establish “an architecture of collective defense and mutual assistance for the benefit of our populations.” The hunger for such regional cooperation goes back to the period when France ended its colonial rule. Between 1958 and 1963, Ghana and Guinea were part of the Union of African States, which was to have been the seed for wider pan-African unity. Mali was a member as well between 1961 and 1963.

But, more recently, these three countries—and others in the Sahel region such as Niger—have struggled with common problems, such as the downward sweep of radical Islamic forces unleashed by the 2011 North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) war on Libya. The anger against the French has been so intense that it has provoked at least seven coups in Africa (two in Burkina Faso, two in Mali, one in Guinea, one in Niger, and one in Gabon) and unleashed mass demonstrations from Algeria to the Congo and most recently in Benin. The depth of frustration with France is such that its troops have been ejected from the Sahel, Mali demoted French from its official language status, and France’s ambassador in Niger (Sylvain Itté) was effectively held “hostage”—as French President Emmanuel Macron said—by people deeply upset by French behavior in the region.

Philippe Toyo Noudjenoume, the President of the West Africa Peoples’ Organization, explained the basis of this cascading anti-French sentiment in the region. French colonialism, he said, “has remained in place since 1960.” France holds the revenues of its former colonies in the Banque de France in Paris. The French policy—known as Françafrique—included the presence of French military bases from Djibouti to Senegal, from Côte d’Ivoire to Gabon. “Of all the former colonial powers in Africa,” Noudjenoume told us, “it is France that has intervened militarily at least sixty times to overthrow governments, such as [that of] Modibo Keïta in Mali (1968), or assassinate patriotic leaders, such as Félix-Roland Moumié (1960) and Ernest Ouandié (1971) in Cameroon, Sylvanus Olympio in Togo in 1963, Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso in 1987 and others.” Between 1997 and 2002, during the presidency of Jacque Chirac, France intervened militarily 33 times on the African continent (by comparison, between 1962 and 1995, France intervened militarily 19 times in African states). France never really suspended its colonial grip or its colonial ambitions.

Breaking the Camel’s Back

Two events in the past decade “broke the camel’s back,” Noudjenoume said: the NATO war in Libya, led by France, in March 2011, and the French intervention to remove Koudou Gbagbo Laurent from the presidency of Côte d’Ivoire in April 2011. “For years,” he said, “these events have forced a strong anti-French sentiment, particularly among young people. It is not just in the Sahel that this feeling has developed but throughout French-speaking Africa. It is true that it is in the Sahel that it is currently expressed most openly. But throughout French-speaking Africa, this feeling is strong.”

Mass protest against the French presence is now evident across the former French colonies in Africa. These civilian protests have not been able to result in straight-forward civilian transitions of power, largely because the political apparatus in these countries had been eroded by long-standing, French-backed kleptocracies (illustrated by the Bongo family, which ruled Gabon from 1967 to 2023, and which leeched the oil wealth of Gabon for their own personal gain; when Omar Bongo died in 2009, French politician Eva Joly said that he ruled on behalf of France and not of his own citizens). Despite the French-backed repression in these countries, trade unions, peasant organizations, and left-wing parties have not been able to drive the upsurge of anti-French patriotism, though they have been able to assert themselves

France intervened militarily in Mali in 2013 to try to control the forces that it had unleashed with NATO’s war in Libya two years previously. These radical Islamist forces captured half of Mali’s territory and then, in 2015, proceeded to assault Burkina Faso. France intervened but then sent the soldiers of the armies of these Sahel countries to die against the radical Islamist forces that it had backed in Libya. This created a great deal of animosity among the soldiers, Noudjenoume told us, and that is why patriotic sections of the soldiers rebelled against the governments and overthrew them. Read more

Breaking Europe’s Hold On Football

John P. Ruehl – Source: Independent Media Institute

09-15-2023 ~ Initiatives from Saudi Arabia and the United States continue to put pressure on Europe’s traditional stranglehold over FIFA.

The 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar brought together nations from around the world, and 1.5 billion people tuned in to watch the final. But while soccer is a source of local pride, passion, and personal and community identity globally, its official governing institution is headquartered in Europe. Founded in Paris in 1904 and now based in Switzerland, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) oversees international soccer promotion and development, from rule changes to hosting rights for major tournaments.

The Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), alongside England’s Premier League (EPL), Germany’s Bundesliga, Spain’s LaLiga, Italy’s Serie A, and France’s Ligue 1, play significant roles in global soccer and generate substantial revenue for FIFA. European clubs and national teams attract top talent, and through “sports diplomacy,” can project their cultural, political, and economic interests to the world and influence FIFA.

This dominance has long been a source of criticism. African teams in 1966 organized boycotts to protest their lack of representation at the World Cup. Even UEFA and João Havelange, president of FIFA from 1974 to 1998, became increasingly critical of each other, while Havelange’s successor, Sepp Blatter, also criticized FIFA’s Eurocentric influence in 2015.

Recently, this strain of critique has become even more apparent. During the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, European teams were rebuked by FIFA to abandon plans to wear pro-LGBT armbands, while UEFA-affiliated teams and FIFA clashed over Qatar’s human rights record in the lead-up to the tournament. But throughout 2023, Europe’s traditional dominance has been challenged by notable developments in Saudi Arabia and the United States.

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, announced in 2016, aims to diversify its economy and attract foreign investment. While hosting and sponsoring motorsports, golf, boxing, and other sports tournaments form part of this, soccer serves as the cornerstone of Riyadh’s attempts to portray and promote the country. This charm offensive has drawn Western allegations of “sportswashing,” wherein sports are used to improve a country’s public image and divert attention from negative actions.

Like other Gulf States, Saudi Arabia has purchased major European teams in recent years. Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund acquired the EPL’s Newcastle United in 2021, and Sheffield United, bought by the Saudis in 2013, will again play in the EPL in the 2023-24 season. The Saudis also reportedly made a multibillion-dollar bid to buy the EPL’s Chelsea, while tournaments like the Supercoppa Italiana and Spanish Super Cup are increasingly held in Saudi Arabia. Read more

A Mass Climate Mobilization Is Taking Place Sunday. Here’s Why It’s Urgent.

Robert Pollin

Economist Robert Pollin analyzes the state of the global green transition in the lead-up to Sunday’s mass protest.

A UN climate report ahead of the upcoming COP28 summit says that governments are failing to cut emissions fast enough for the planet to avoid an unmitigated disaster and calls in turn for the phasing out of fossil fuels. In the wake of the hottest summer on record, climate advocates have organized a “March to End Fossil Fuels” in New York City as part of the wave of global mobilizations with the aim of putting an end to the poisons that are killing the planet. The action will take place Sunday, September 17.

Amid this crucial mobilization, the climate movement is working hard to expose the roots of this crisis and chart an alternate course, wrestling with questions such as: Why do governments continue to subsidize fossil fuels? Aside from the obvious resistance of the fossil fuel industry, what are the economic and technological challenges we would face by moving to a post-fossil fuel future? How do we actually get to zero emissions?

Robert Pollin, one of the world’s leading progressive economists and an expert on the macroeconomics of climate change and energy, tackles these questions in an extensive and exclusive interview for Truthout. Pollin is distinguished professor of e conomics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He has published scores of books and articles on jobs and macroeconomics, labor markets, wages and poverty, and environmental and energy economics. He was selected by Foreign Policy Magazine as one of the “100 Global Thinkers for 2013.” His latest book, coauthored with Noam Chomsky, is Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet.

C. J. Polychroniou: On Wednesday, September 6, the European Copernicus Institute reported that the summer of 2023 was the hottest ever recorded in history by a large margin, prompting in turn UN Secretary-General António Guterres to issue a statement saying “climate breakdown has begun.” And speaking of the UN, on Friday, September 8, it released an assessment of the progress on cutting emissions in which it said that countries are failing to make good on their commitments to curb emissions and that, subsequently, “there is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all.”

First, what’s the current picture of energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and that of renewable energy, respectively, and why is it that eight years after the Paris Agreement the world is still falling short of its climate goals?

Robert Pollin: To have any chance of moving onto a viable global climate stabilization path, the single most critical project at hand is straightforward. It is to phase out the consumption of oil, coal and natural gas, so that, by 2050, fossil fuel consumption for producing energy will have fallen to zero. This is because producing and burning fossil fuels to produce energy is responsible for about 90 percent of all CO2 emissions.

As of the most recent data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the leading mainstream organization focused on global energy market conditions, global CO2 emissions were at around 36 billion tons in 2021. This represents a roughly 70 percent emissions increase since 1990 and a 14 percent increase just since 2010. More to the point, according to the IEA’s estimates for future emissions under two alternative realistic scenarios — what they term as their “stated policies” and “announced pledges” scenarios — emissions will fall barely at all by 2030 and will not come close to achieving the zero emissions target by 2050.

The IEA does also develop a scenario through which the world can reach zero emissions by 2050. The difference between the IEA’s stated policies and announced pledges scenarios relative to their net zero emissions by 2050 scenario is what the IEA demurely terms an “ambition gap.” The question for getting to zero emissions is therefore to figure out how to close this “ambition gap.”

Closing this ambition gap must, of course, recognize that people do still need to consume energy to light, heat and cool buildings, to power cars, buses, trains and airplanes, and to operate computers and industrial machinery, among other uses. As such, to make progress toward climate stabilization requires a viable alternative to the existing fossil fuel dominant infrastructure for meeting the world’s energy needs. Read more

Colombia, From The Guerrilla To The Ballot Box

A conversation with Pastor Alape, former guerrilla mayoral candidate for the Comunes Party.

On May 4, 2023, during the International Summit on Nonviolence held in Antioquia, Colombia, a handshake shocked those who were present. The handshake was between two men with vastly different histories. One of the men was Daniel Gaviria, whose father—Guillermo Gaviria, former governor of Antioquia—was killed in 2003 when he was a hostage of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP). The other man was Pastor Alape, former commander of the FARC-EP. Gaviria said that the handshake took place because Pastor Alape was “taking steps toward nonviolence.” “That gives me confidence and leads me to extend forgiveness to him,” said Gaviria.

Pastor Alape commanded one of the FARC-EP’s regions and was part of its highest body, the Estado Mayor Central. FARC-EP, founded in 1964, signed a peace agreement with the Colombian state in 2016. It was then transformed into the Comunes Party, comprising former guerrillas and members from various social movements. This party, which has contested elections, focuses its attention on the need to implement the peace agreement and advance the cause of social justice in Colombia. One of the lingering problems in the country is the full incorporation of former guerrilla fighters into the country’s social and political life.

Not long after the handshake, we spoke to Pastor Alape about the process of reintegration. He told us that as part of this process, he has decided to be the first former member of the national leadership of the FARC-EP to run for regional elections. Pastor Alape is running to be the mayor of Puerto Berrío in Antioquia, where he grew up. In his new civilian life, the former combatant decided to combine the name given to him by his parents (Félix Antonio Muñoz Lascarro) with the name given to him by the guerrilla struggle (Pastor Alape) and be called Pastor Lisandro Alape Lascarro. Earlier in July, he said that he joined the FARC-EP to “change the country with a lead” and now through Comunes he wants to “change it with the votes.”

Resistance of a Legal Kind

In 1974, Pastor Alape—at the age of 15—joined the Communist Youth. That year, a pact that was formed in 1958 between the Liberal and the Conservative parties to govern together as a National Front ended. It was this political turmoil that led to the armed struggle of the FARC-EP and other groups in the 1960s. But, in 1974, the Colombian Communist Party (PCC)—which had been underground—became politically active again. His work in the Communist Youth from that time, Pastor Alape told us, allowed for his “political formation through legal resistance.” This time was short-lived, and when the violence restarted, Pastor Alape joined the FARC-EP.

After 53 years of armed resistance, the warring parties signed a historic peace agreement in Havana in 2016 and Comunes entered the electoral domain. As part of the peace agreement, to incorporate Comunes into legal politics, the party is represented in Congress by 10 members. But it has thus far not been able to win many seats in the different local and regional bodies. In the October 29 regional elections, Comunes will contest 145 seats, including for the mayor’s office in Puerto Berrío, which Pastor Alape is running for.

A Community That Survives

“I have not been very fond of electoral politics,” Alape told us. “But when I arrived in the town of Puerto Berrío and met with old and new friends and family, these interactions gave me the impetus to try and use the political system to initiate state action on behalf of marginalized communities.”

Puerto Berrío or El Pueblo, as Pastor Alape calls it, is a small municipality of around 51,000 people in the province of Antioquia, which is located on the banks of the Magdalena River. On December 17, 1979, Pastor Alape left his home on a small boat on this very river to go to Matarredonda in Chaparral (Tolima) to join the FARC-EP. Now, he walks along the riverbanks and campaigns to become its mayor. Read more

Ancient Roots: A Promising New Project To Organize Humanity’s Universal Heritage

Eric Laursen

An international group of researchers and data scientists are creating a comprehensive database of the world’s archaeological knowledge—and changing our understanding of humans’ prehistoric heritage.

Archaeology isn’t what it was in Indiana Jones’s heyday. The traditional image of the khaki-clad researcher scrambling over an excavation site with rock hammer and camel-hair brush has been supplemented by aerial and satellite photography, CT scanners and 3D modeling, and lidar that can isolate the smallest details of long-buried settlements. What archaeologists do with the artifacts and data they gather is changing dramatically as well, as they use network science and new software tools to map the complex connections between regional economic networks in the millennia before written history.

With this new, technology-driven approach, researchers can form a far more comprehensive picture of early communities’ ties with other human clusters sometimes thousands of miles away, by examining the goods and raw materials they exchanged and tracing these from their points of origin to the far-flung places where they were abandoned and then rediscovered centuries later. This is yielding additional insights into social inequality and power relations within communities, differences and similarities between communities living next to each other, and patterns of migration and settlement.

“You get more of a sense of a dynamic,” says Tim Kerig, an archaeologist at Kiel University’s ROOTS Cluster of Excellence in Social, Environmental, and Cultural Connectivity in Past Societies, in Germany, “of people coming from other places and how, over the generations, they filled that landscape. So we’re looking at the whole system, over not centuries but millennia.”

Network science is the study of complex relationships—and probable relationships—between physical, biological, social, and cognitive phenomena. Applying network science to archaeology was an idea in the minds of researchers as far back as the 1960s, says Kerig, whose own work focuses on the European Neolithic period—from about 8000 BC to 2000 BC—and the evolution of social inequalities. But while interest grew in succeeding decades, archaeologists lacked the tools to easily collate and analyze the millions of data points that had been gathered over many decades. The few efforts to do so proceeded punishingly slowly, on top of which, there was less interest at the time in exploring the connections that material and economic exchanges between far-flung communities could reveal.

“Sociological questions were mostly answered by looking at goods that were found in graves—the ‘sphere of kings’—which tended to be highly valued luxury items,” Kerig says, while archaeologists were less interested in “the daily stuff”: fragments of flint or stone objects or implements that made up the fabric of most people’s everyday lives. This was partly due to an overabundance of these humbler items. “Don’t forget that at a Stone Age site in Denmark, for example, you might have 100,000 artifacts to deal with, and they all look to most of us exactly the same.”

“Big Exchange” is the name of a project that an international cluster of scholars and data scientists, including Kerig, launched in 2020 with the aim of using digital tools to break down the barriers to applying network science to archaeology. The most critical hurdle they faced was overspecialization. Traditionally, archaeologists have focused on specific objects or raw materials—amber, obsidian, jade, flint, other metals—rather than the totality of findings at a given site, which prevented them from seeing the totality of that community’s networks of exchange. Big Exchange’s first objective is to create a database that collates all these materials and makes them available for more sophisticated, cross-referenced study and analysis.

“The approach of our project is to include all recordable raw materials, their find locations and places of origin in the analysis for the period from the end of the Middle Stone Age [or Mesolithic, 10,000 years ago,] to Antiquity,” Johanna Hilpert, a Big Exchange postdoc researcher at the ROOTS Cluster, told Phys.org in July 2023. “This can only be done by means of network analysis and with AI [artificial intelligence].” Read more

How Countries Prepare For Population Growth And Decline

John P. Ruehl – Source: Independent Media Institute

09-11-2023 ~ Around the world, diverse initiatives are being introduced to manage population changes.

In early 2023, India surpassed China as the most populous country in the world with the latter having 850,000 fewer people by the end of 2022—marking the country’s first population decline since famine struck from 1959 to 1961.

While this reduction may seem modest considering China’s 1.4 billion population currently, an ongoing decline is anticipated, with UN projections suggesting that China’s population could dwindle to below 800 million by 2100.

Populations fluctuate through immigration, emigration, deaths, and births. China’s previous one-child policy, enforced from 1980 to 2015, and the resulting gender imbalance slowed its birth rate. The Chinese government is now trying to boost birth rates, including by discouraging abortion.

The Malthusian population growth model, proposed in the 1700s, suggested that populations grow exponentially and outpace resource availability until inevitable checks, such as famine, disease, conflict, or other issues, cause it to drop. During the high global population growth rates of the early 1960s, these concerns abounded. Yet around the world, population growth has slowed dramatically, and in China and many other countries, natural decline is already underway.

A 2020 study published in the Lancet medical journal revealed that based on current population trends, more than 20 countries are on track to halve their populations by 2100. The Pew Research think tank, meanwhile, declared that 90 countries will see their populations decline by 2100, while the Center of Expertise on Population and Migration (CEPAM) predicts the global population will peak at 9.8 billion around 2070 to 2080.

The fear of a shrinking and aging population looms over governments and economists alike. Increased payments toward pension and social welfare systems will strain a reduced labor force, while younger populations also contribute more to economic growth and innovation. Countries may also experience a reduction in their global influence—not least because of a smaller population available for military service.

Various metrics gauge fertility and birth rates, but the total fertility rate (TFR), which measures the number of children a woman will have in her lifetime, is the most common. Yet achieving replacement level fertility rates, typically 2.1 children per woman, has proven challenging.

The decline in global fertility rates can be attributed to societal and cultural shifts, family planning initiatives, wider access to contraception, improved infant mortality rates, increased cost of child-rearing, urbanization, delayed marriages and childbirth due to educational and career pursuits, and social welfare systems reducing reliance on familial support.

A case in point is Japan, whose population peaked at 128 million in 2008 and has since shrunk to below 123 million. It is poised to decrease to 72 million by century’s end, its decline sustained by a low fertility rate, an aging population (almost 30 percent of the population is 65 or older), and limited immigration. Initiatives to slow this decline include changing immigration laws and government-sponsored speed dating.

Remarkably, despite hitting a record low in 2022, Japan’s TFR is now higher than China’s and South Korea’s. Since 2006, South Korea has invested more than $200 billion in establishing public daycare centers, free nurseries, subsidized child care, and other initiatives to boost its TFR. But at 0.78, South Korea’s TFR remains the world’s lowest. South Korea’s government also introduced immigration reforms in the early 21st century, all while leading the world in automation with 1,000 robots per 10,000 employees—more than double of second-ranked Japan. Read more